Why a Formation in Catholic Culture is Central to Catholic Education

How Thomas More College has captured the essence of a Catholic education through its guilds and the promotion of creativity in art, music and literature. I recently read a book by Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI that I would recommend to all (h/t Stratford Caldecott for telling me about it). It is called A New Song for the Lord - Faith in Christ and Liturgy Today. The publisher, Crossroads, decided to put the following quotation from text prominently on the cover: 'How we attend to the liturgy determines the fate and faith of the Church.' This last part is what drew me to it particularly. I wanted to know more because it seemed to support my understanding that it is the liturgy that forms most powerfully the worldview of the believer and that, in turn, is what shapes the culture most powerfully.

How Thomas More College has captured the essence of a Catholic education through its guilds and the promotion of creativity in art, music and literature. I recently read a book by Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI that I would recommend to all (h/t Stratford Caldecott for telling me about it). It is called A New Song for the Lord - Faith in Christ and Liturgy Today. The publisher, Crossroads, decided to put the following quotation from text prominently on the cover: 'How we attend to the liturgy determines the fate and faith of the Church.' This last part is what drew me to it particularly. I wanted to know more because it seemed to support my understanding that it is the liturgy that forms most powerfully the worldview of the believer and that, in turn, is what shapes the culture most powerfully.

It was written in 1996, before his classic book on the liturgy, the Spirit of the Liturgy. There is greater discussion in this book than in the later one of the connection between the person of Christ and the liturgy; and also, happily for me (as the title suggests), about the general connection between liturgy and culture. He talks in depth, for example, about the the forms of music appropriate for the liturgy and how important the connection between this and contemporary culture is. In regard to this, he gives a critique of modern music forms (displaying a surprising degree of knowledge about them - even differentiating between rock and pop!) and explaining why they are, for the most part inappropriate for the liturgy and in many cases not good in any other situation either. He then goes on to say that the response to this cannot be simply a recovery of past forms. We must always also be creative and produce new forms that connect with people today. Rejecting what is new simply because it is new is not an option.

He says (p127): "The level of a culture is discernible by its ability to assimilate to come into contact and exchange and to do this synchronically and diachronically. It is capable of encountering other contemporary cultures as well as the development of human culture in the march of time. This ability to exchange and flourish finds its expression in the ever recurring imperative 'Sing the Lord a new song'. Experiences of salvation are found not only in the past, but occur over and over again: hence they also require the ever new proclamation of God's contemporaneity, whose eternity is falsely understood if one interprets it as being locked in decisions made 'from time immemorial'. On the contrary, to be eternal means to be synchronous with all times and to be ahead of all times.:

Then he tells us also (p133) that the test of whether or not the creativity that gives rise to the 'new song' originates from God is that it will connect with the ordinary person and not just the cultured elite:

Then he tells us also (p133) that the test of whether or not the creativity that gives rise to the 'new song' originates from God is that it will connect with the ordinary person and not just the cultured elite:

He says: "It is precisely the test of true creativity that the artist steps out of the esoteric and knows how to form his or her intuition in such a way that the other - the many - may perceive what the artist has perceived."

This may be a surprise to some, who assume that in order to be popular the artist, writer or composer must compromise on his principles and stoop down to the level of the masses. In fact, the Pope is telling us, it is the opposite: unpopular artists are so because don't know how to scale the heights facing them and reach up to the many. It is the contemporary expressions that connect most powerfully with man today, good or bad. When the work of the artists and composers who are creating today is good enough, it will speak to the many and overwhelm what is currently popular and inferior to it.

This supports the idea, which I have stated on other occasions, that the main task ahead of us if we want to be successful in the evangelisation of the culture, is not the education of the masses, but the formation of the artists so that they know how to create powerfully beautiful contemporary forms that re-order contemporary culture and speak to the masses. Each artist must break out beyond his own social circle of friends at dinner parties and speak to 'the many' in the universal language of beauty.

But, one might ask, should this process of a formation of creators of culture be the concern of a Catholic liberal arts college? Isn't this focus on culture too concerned with applications than with pure wisdom? Some may say so. This process of inculturation of the students and their formation as creators of a new and beautiful Catholic culture is often treated as a recreational add-on to the core aspects of education. But, if we are to accept the documents of the Church written on the nature of a Catholic education, a cultural formation is instrinsic and central to what a Catholic education ought to be:

'No less than other schools does the Catholic school pursue cultural goals and the human formation of youth. But its proper function is to create for the school community a special atmosphere animated by the Gospel spirit of freedom and charity, to help youth grow according to the new creatures they were made through baptism as they develop their own personalities, and finally to order the whole of human culture to the news of salvation so that the knowledge the students gradually acquire of the world, life and man is illumined by faith.' (Gravissimum Educationis, 8, a statement on Catholic education by the Second Vatican Council, 1965)

'No less than other schools does the Catholic school pursue cultural goals and the human formation of youth. But its proper function is to create for the school community a special atmosphere animated by the Gospel spirit of freedom and charity, to help youth grow according to the new creatures they were made through baptism as they develop their own personalities, and finally to order the whole of human culture to the news of salvation so that the knowledge the students gradually acquire of the world, life and man is illumined by faith.' (Gravissimum Educationis, 8, a statement on Catholic education by the Second Vatican Council, 1965)

or elsewhere: 'A school is, therefore, a privileged place in which, through a living encounter with a cultural inheritance, integral formation occurs'. (The Catholic School, 26; published by the Congregation for Education, 1977)

This inculturation forms the person in accordance with the ultimate goals of love of God, through worship, which leads to personal transformation; the ove of God through love of man by seeking evangelisation of the world

'A Christian education...has as its principal purpose this goal: that the baptized, while they are gradually introduced the knowledge of the mystery of salvation, become ever more aware of the gift of Faith they have received, and that they learn in addition how to worship God the Father in spirit and truth (cf. John 4:23) especially in liturgical action, and be conformed in their personal lives according to the new man created in justice and holiness of truth (Eph. 4:22-24); also that they develop into perfect manhood, to the mature measure of the fullness of Christ (cf. Eph. 4:13) and strive for the growth of the Mystical Body; moreover, that aware of their calling, they learn not only how to bear witness to the hope that is in them (cf. Peter 3:15) but also how to help in the Christian formation of the world that takes place when natural powers viewed in the full consideration of man redeemed by Christ contribute to the good of the whole society.' Gravissimum Educationis, 2

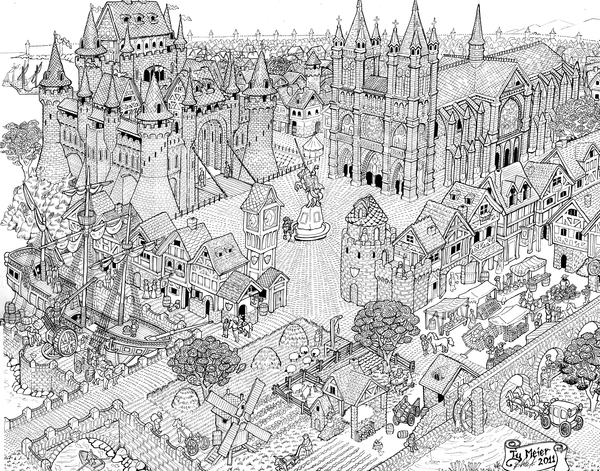

Reflecting this, Thomas More College places an emphasis on creativity in the arts and humanities (as well as analysis of past great works); and this is why we have a Composer-in-Residence, Paul Jernberg; a Writer-in-Residence, Joseph Pearce; and myself, Artist-in-Residence. This is why also, we have instituted the guilds at the college - we want to develop the creative faculty in the students and instill in them the habit of directing it to the common good. It is also an important part of the formation of the student - and essential part of the learning process. Even those who are not naturally poetic, artistic or musical will learn more about the good and the true through the participation in the creation of beauty - 'the good made visible' as John Paul II referred to it in his Letter to Artists. This is in accord with the principle articulated by St Anselm of Canterbury who said that something is known most fully when experienced.

And this culture cannot be understood except as an extension of the activity of the human person by which we are fully human, the worship of God. All the cultural must be understood by the students as something that is derived from and points to the liturgical culture and hence liturgical life.

I would like to thank Mark Brumley writing in the National Catholic Register and his excellent little article on the purpose of a Catholic education, which first directed me to these Church documents.

Those who are interested in reading Joseph Pearce's many wonderful books on the faith, including his recent autobiography, Race with the Devil: My Journey from Racial Hatred to Rational Love can look on Amazon, here.

I conclude this with some recordings of the music of Paul Jernberg from his Mass of St Philip Neri.

https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC9443A8SSmktZiNlIlRA9Rg?feature=watch