St Matthew the Evangelist from the Lindisfarne Gospels - lessons for all who wish to pray...and for all who wish to paint

To mark the Feast of St Matthew here is the illumination from the 8th century British manuscript (the original is in the British Library). There are profound lessons here for those who wish to pray, and for those who wish to paint...or both. This simple painting, which is over 1200 years old and was created by an obscure monk working on a bleak island of the northeast coast of England in the North Sea can tell us so much. It reveals truths about St Matthew, and from its style we can discern things about the whole history of Christian art. These are lessons that budding artists can apply today, even if we want to paint in completely different styles such as the baroque.

To mark the Feast of St Matthew here is the illumination from the 8th century British manuscript (the original is in the British Library). There are profound lessons here for those who wish to pray, and for those who wish to paint...or both. This simple painting, which is over 1200 years old and was created by an obscure monk working on a bleak island of the northeast coast of England in the North Sea can tell us so much. It reveals truths about St Matthew, and from its style we can discern things about the whole history of Christian art. These are lessons that budding artists can apply today, even if we want to paint in completely different styles such as the baroque.

To be able to see these things in the painting we will look first at the historical context. This little painting even tells us about the history of Britain! Art historians - (and the font of all knowledge, Wikipedia of course!) - will describe the style of this art as 'insular' or 'hiberno-saxon'. This refers to the Celtic style of art and literature of the Christians who remained in the British Isles and Ireland after the retreat of the Romans. It is viewed as 'insular' in two ways - first more literally as it belongs to the islands of Britain and Ireland; and secondly because it is often viewed as a style that is distinct from others of this period. There is a third reason particular to this gospel, in that Lindisfarne, the site of an abbey, is an remote island off the coast of Northumberland in northeast England. The artist of this painting was a monk called Eadfrith and he later became the abbot of Lindisfarne Abbey.

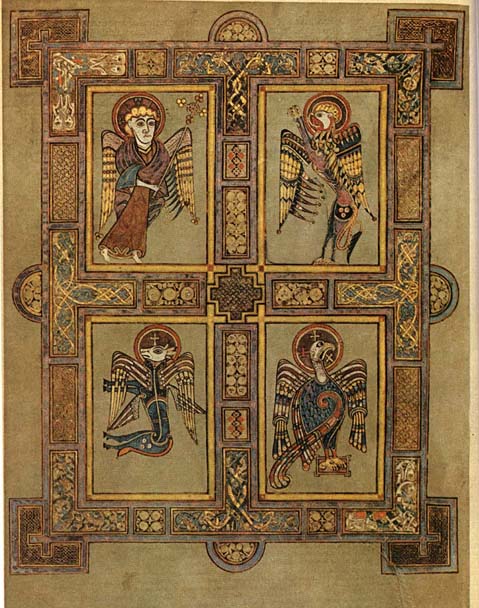

The British islanders who remained after the retreat of Roman troops in the 5th century were culturally Roman and so wrote in Latin. Gradually over the following centuries they were overwhelmed by the incursions of German and Nordic tribes. Even in the 8th century, there were pockets of Latin culture left and most of the Lindisfarne Gospel is written in Latin. In this page 'Mattheus' is in Latin and he is referred to as a saint with the word 'Hagios' (Greek). Matthew is depicted writing his gospel with the figure of the winged man, the symbol of Matthew, standing on his shoulder (imago hominus - the image of a man). This, is one of the four faces of the cherub described by Ezekiel in his vision. Over time Germanic and Viking culture dominated more and more and by the 9th century Latin was not so widely spoken; and so on other pages the original Latin gospel text is translated into the vernacular in red ink. The curtains are present to indicate that the person is inside and are drawn back to reveal the scene to the observer. Some commentaries refer to this as a symbolic unveiling by which the truth is revealed. I have to be honest and say I do not know who the figure peeping out from behind the curtain is. Can anyone help me here? The painting is ink on vellum, made from the skin of sheep. Vellum is a material that is resistant to decay over time and was also very expensive and so rare. This is one reason, incidentally, that so many Icelandic sagas remain I found out recently - because there were so many sheep on Iceland and such a small population, vellum was more plentiful and so unusually they recorded a much higher proportion of their folk tales on vellum and this is how we know of so many today. Tolkien was an expert in all of these ancient forms of British and of the Icelandic language and literature - so this is the world that fired his imagination so strongly. Back to this painting - the style of Lindisfarne gospels art is certainly distinctive. While retaining its unique look, it still conforms largely to the iconographic prototype, which governed Christian art, East and West from about the 5th century through to the 13th century. This is a Western variant, so while it doesn't look like a Russian icon, it still conforms in many ways to the same prototype. So this has the characteristic flatness and lack of perspective that one expects in an icons, revealing the heavenly dimension which is outside space. In order to emphasize this the bench upon which Matthew is sitting is in inverse perspective. He has his feet on a pedestal indicating a holy person. There is one little anomaly however. A feature that pulls it away from strict conformity to the icon is the fact that the symbolic winged man is in profile. Generally, in icons faces are in three quarter profile or full face (like the other two figures) indicative of a saint who is happy to reveal is person to the viewer because in his purified state he has nothing to hide. Generally images from this period conformed fully to the iconographic prototype. Here is a portrayal of the symbol of St Matthew along with those of the four evangelists in the Book of Kells, which was produced about 100 years later and is considered of the same period and style. We can see St Matthew portrayed in three quarter profile, the standard for human forms. I don't know why Eadfrith departed from this in his version. It might be a mistake or even an act of defiance, or perhaps a little bit of ignorance.  There is another aspect to this and it relates to how we know what an icon is. What is it that makes an icon rather part of the gothic tradition? Anyone who has done an icon painting class or read a book about icons is aware that there are stylistic principles which govern what they do. What many do not know is that the rules that they are being given are a modern construct. They were for the most part written and popularized in the 20th century. I have researched and asked many people and am not aware of any writings prior to the recent period that represent a codification of the stylistic elements that make in icon an icon, rather than, say, a piece of gothic art. There are no writings by Church Fathers for example. The rules that you come across in the books were devised by a group of Russian ex-patriots in Paris, especially influential were two men called Ouspensky and Lossky. They looked at the images that they judged to be good and worthy of veneration and the devised a set of rules that seem to apply to them to aid people to create art in a similar style in the future. To my knowledge no such code was in existence in writing when Eadfrith was active. We do not know the degree to which the style, which seems to have been preserved by force of tradition, was directly linked to the theology of style in the way that it is presented today. Perhaps, in fact, there was more leeway than we imagine and Eadfrith was just making what would have seemed a legitimate artistic decision. Make no mistake, people such as Ouspensky and Lossky did a great job, in my opinion. they provided a set of guidelines by we have seen the re-establishment of what was in the 19th century a wayward tradition in Russian and Greece, into a strong and clearly defined form so that icon painters today can be every bit as good as the top icon painters of the past. These Russians were not without their own agenda in setting this down however. They were Eastern Orthodox and deliberately set down the rules so as to reflect their belief that the Western forms of art were inferior ('degenerate' is the term I have heard used to refer to the gothic and the baroque for example) . Catholics should be aware of this. The idea that all sacred art has to look like an icon is, from the point of view of the Catholic Church flat wrong. Unfortunately that doesn't stop many Catholics unquestioningly accepting and repeating the anti-Catholic rhetoric that they have heard in their icon painting class. Contemporary Orthodox commentators are motivated to make Western forms that were created prior to the schism between East and Western Church (around 1000AD) , such as this example of insular art, fit in with the iconographic prototype because it supports and argument that Christian culture was unified before the schism and then fragmented afterwards. Then, the argument runs, we can see that the Eastern Churches remain faithful to the original forms of Christianity, while it is the Roman Church that has veered away. We don't have space here to give the full theology of the image that governs the Western traditions in art, but to give you a general picture of what is legitimate for the liturgy and what is not, I take my lead from Benedict XVI. He said in his book, the Spirit of the Liturgy that the icon is appropriate for the liturgy (in this he agrees with the Orthodox) but in addition, he says, for the Roman Rite, the gothic and the baroque styles are appropriate too. So you can continue to enjoy and worship with paintings in the style of people such as Duccio and George De La Tours. I would say that the one thing where the Eastern Church does lead the West is in the reestablishment of these traditions. We are 60 years behind in propogating a theology of style of the uniquely Western styles, in the way that it has been done for icons. My book, the Way of Beauty, was an attempt to do for the theory of the gothic and the baroque traditions what Lossky and Ouspensky did for the iconographic tradition. Below, classic baroque - St Matthew and the Angel by Guido Reni of the 17th century - with the angel...legitimately... in profile; and the same evangelist by Duccio

There is another aspect to this and it relates to how we know what an icon is. What is it that makes an icon rather part of the gothic tradition? Anyone who has done an icon painting class or read a book about icons is aware that there are stylistic principles which govern what they do. What many do not know is that the rules that they are being given are a modern construct. They were for the most part written and popularized in the 20th century. I have researched and asked many people and am not aware of any writings prior to the recent period that represent a codification of the stylistic elements that make in icon an icon, rather than, say, a piece of gothic art. There are no writings by Church Fathers for example. The rules that you come across in the books were devised by a group of Russian ex-patriots in Paris, especially influential were two men called Ouspensky and Lossky. They looked at the images that they judged to be good and worthy of veneration and the devised a set of rules that seem to apply to them to aid people to create art in a similar style in the future. To my knowledge no such code was in existence in writing when Eadfrith was active. We do not know the degree to which the style, which seems to have been preserved by force of tradition, was directly linked to the theology of style in the way that it is presented today. Perhaps, in fact, there was more leeway than we imagine and Eadfrith was just making what would have seemed a legitimate artistic decision. Make no mistake, people such as Ouspensky and Lossky did a great job, in my opinion. they provided a set of guidelines by we have seen the re-establishment of what was in the 19th century a wayward tradition in Russian and Greece, into a strong and clearly defined form so that icon painters today can be every bit as good as the top icon painters of the past. These Russians were not without their own agenda in setting this down however. They were Eastern Orthodox and deliberately set down the rules so as to reflect their belief that the Western forms of art were inferior ('degenerate' is the term I have heard used to refer to the gothic and the baroque for example) . Catholics should be aware of this. The idea that all sacred art has to look like an icon is, from the point of view of the Catholic Church flat wrong. Unfortunately that doesn't stop many Catholics unquestioningly accepting and repeating the anti-Catholic rhetoric that they have heard in their icon painting class. Contemporary Orthodox commentators are motivated to make Western forms that were created prior to the schism between East and Western Church (around 1000AD) , such as this example of insular art, fit in with the iconographic prototype because it supports and argument that Christian culture was unified before the schism and then fragmented afterwards. Then, the argument runs, we can see that the Eastern Churches remain faithful to the original forms of Christianity, while it is the Roman Church that has veered away. We don't have space here to give the full theology of the image that governs the Western traditions in art, but to give you a general picture of what is legitimate for the liturgy and what is not, I take my lead from Benedict XVI. He said in his book, the Spirit of the Liturgy that the icon is appropriate for the liturgy (in this he agrees with the Orthodox) but in addition, he says, for the Roman Rite, the gothic and the baroque styles are appropriate too. So you can continue to enjoy and worship with paintings in the style of people such as Duccio and George De La Tours. I would say that the one thing where the Eastern Church does lead the West is in the reestablishment of these traditions. We are 60 years behind in propogating a theology of style of the uniquely Western styles, in the way that it has been done for icons. My book, the Way of Beauty, was an attempt to do for the theory of the gothic and the baroque traditions what Lossky and Ouspensky did for the iconographic tradition. Below, classic baroque - St Matthew and the Angel by Guido Reni of the 17th century - with the angel...legitimately... in profile; and the same evangelist by Duccio

— ♦—

My book the Way of Beauty is available from Angelico Press and Amazon.