In the film, The Greatest Story Ever Told, made in 1965 John Wayne plays a cameo role of the centurion who saw Jesus die, as related in Mark’s gospel:

And when the centurion, who stood there in front of Jesus, saw how he died, he said, 'Surely this man was the Son of God!' (NIV, Mark 15:39)

So John Wayne had one line: ‘Surely, this man was the Son of God.’ The late English film critic Barry Norman used to tell a story that on the first take after Wayne delivered the line, the director, George Stevens, shouted, ‘Cut,’ and came over to him. ‘That’s great John,’ Stevens said. ‘But we need more emotion, give us some awe.’ So, in the second take Jesus expired and John Wayne looked up at him and said: ‘Aw, surely this man was the Son of God.’ I have no idea if this really happened, but Norman’s intention was to make fun of Wayne for wooden acting.

In fact, I have more sympathy for Wayne in this tale than perhaps I ought. I have always felt that the best actors erred, if they did so, towards underacting, rather than overacting. I find it difficult to go to amateur dramatics because most err in the other direction and overact. Most actors, it seems are taught to convey emotion whilst reading words. I accept that the portrayal of emotion has to be part of it, but the best actors, it seems to me, will suggest emotion through their art, but will engage the viewer more powerfully because they allow for a personal response to their portrayal by underplaying it and hence drawing in the imagination.

The risk of overplaying the emotion is that it tends to be melodramatic. In this case the emotional portrayal is dominant to the degree that it stifles the imagination of the viewer. It is so dominant that it allows for no personal response unless it happens to coincide with what the actor does. The skilled underplayed part doesn’t dictate what emotion I should feel, rather it places me there so that my imagination can supply it. The skilled actor therefore must portray enough emotion to stimulate the imagination, but not so much that it stifles a personal response. I happen to think that John Wayne was skilled at striking this balance on screen because to a degree he allowed the words to speak for themselves and let his screen presence do the rest.

Storytelling, perhaps by reading from a book aloud, is not acting and the need to let the words speak for themselves is even greater than in drama. While acting, which is just a highly developed skill of ‘let’s pretend’, does require an authentic portrayal of emotion to some degree, storytelling, I suggest does not.

One of the best storytellers I have encountered was Garrison Keillor. For years he gave a monologue in his show The Prairie Home Companion, which was a story about the week’s events in a fictional town in Minnesota, Lake Wobegon. For the most part, he just told the story in a detached and unemotional way and really did allow the words, which he had written with great care, to speak for themselves. He did change his intonation in the dialogue a little so that you could distinguish one character from another as you were listening. And at key moments he did reflect a little of the emotion of a character, but it was always understated to a degree. Few actors would dare show such restraint, I suggest, and Keillor never became the character in the way that an actor would, it was always Garrison Keillor giving you words.

Again, the value of this is that it gives the listener space in their imaginations to create a rich personal picture of what is going on. Actors, even highly-skilled actors, are often not good storytellers because they often seem to want to act out the story too much, rather than tell it. It is difficult for them to step out of the way and let the words alone reveal the sense that the author wished to communicate.

Proclaiming the gospel, I suggest, is telling a story, but even more than any other, it is important that the words do the talking and the reader is not dictating the emotion to the listener. For this reason, I find the injection of emotion on the part of the lector at Mass utterly inappropriate. If ever there is a situation in which we want to give room for a personal response to the text, this is it. The less that the reader emotes and the more he keeps his own personality out of the way, the more, I suggest that God speaks to each person present through the words that he authored.

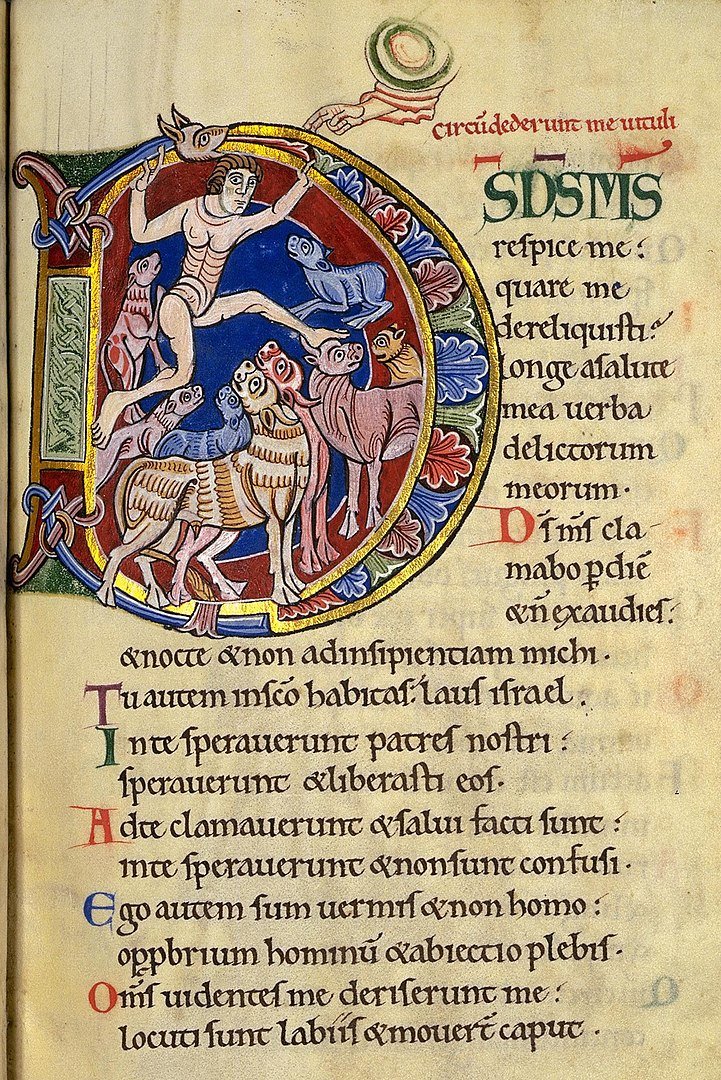

The same is true of the psalms, which are highly emotional in content. This emotional poetry is written in the original language in what Gerard Manley Hopkins called ‘sprung rhythm’ and this poetic structure will be present also in good translations. If the reader observes this rhythm, which is simply to allow for a set number of emphasized syllables in each line, then it is difficult to ‘act out’ the words of the psalmist. For the same reasons as given above, this is a good thing, I suggest. The Holy Spirit speaks to us personally and powerfully through the text simply by our grasping the sense of what they say, and the injection of any emotion on the part of the reader is stifling that personal response.

For this reason, it seems to me, that traditional melodies for chanting the psalms and intoning the text are unemotional in nature. They are beautiful but do not impose, any emotion onto the text. This is why, within reason, just about any authentic psalm tone works with any psalm. It engages us but directs us to the words on the page so that we can respond individually to them.

When melodies that have an emotional content embedded within them are used to sing the psalms, then it becomes less prayer and meditation, and more a performance that distracts from what the psalms are saying.