SingtheOffice.com has been upgraded so as to provide daily Offices from the English prayerbook tradition, fully pointed for Gregorian chant, and compliant with the rubrics of Divine Worship: Daily Office (Commonwealth Edition) of the Personal Ordinariate of Our Lady of Walsingham.

Where Have All the *!*?-ing Psalms Gone?

How to Address the Crisis in Fatherhood Head On through Prayer

In this article I describe how it is prayer, above all, that binds families together; and the most powerful form of prayer we can pray in the home is the liturgy of the hours. Furthermore, with the father leading the prayers, we are opening the way for a powerful driving force that has effect not only within the family but also beyond the four walls of our home.

I first posted this exactly three years ago. It was in part a desire to see this home-based driving force for change that lead to the writing of the book on prayer in the home, The Little Oratory.

In this article I describe how it is prayer, above all, that binds families together; and the most powerful form of prayer we can pray in the home is the liturgy of the hours. Furthermore, with the father leading the prayers, we are opening the way for a powerful driving force that has effect not only within the family but also beyond the four walls of our home.

I first posted this exactly three years ago. It was in part a desire to see this home-based driving force for change that lead to the writing of the book on prayer in the home, The Little Oratory.

The word Oratory, incidentally means in English 'House of Prayer'. When I used to go to the London Oratory - the wonderful Catholic church in England whose liturgy was so influential in my conversion - I used to see these words on the walls around the sanctuary: domus mea domus orationis vocabitur. It was a quote from Isaiah 56:7 which is echoed in Matthew's gospel - my house shall be called a house of prayer, says the Lord. This isn't the full quote, I know there's some Latin missing there but I am handicapped by a combination of poor Latin skills and a bad memory; but here's the point, I wanted to include at least part of it because it shows the word 'orationis' - 'of prayer' - so that you can make the connection with the title of the book.

We chose this title because we wanted to communicate the idea that even the most humble house can be transformed into a house of prayer in accordance with the ideal articulated in Isaiah, and just as the London Oratory, in all its wonderful glory does. This is how a house becomes a home, however many people live there. The book we have written, we hope, helps us to fulfill that ideal and it places fathers, when we are talking of families, once more right at the centre of family and in right relationship with all others. As one might say, the father is the head and the mother is the heart. Both are necessary!

I will be doing a series of postings over the next few weeks that draw out themes discussed in more detail in the book. Anyway, here is the article....

In the exercise of the lay office in the liturgy each person participates in the sacrifice made by Christ, the supreme act of love for humanity. When we are advocates in prayer in this liturgical setting, the participation in the liturgy becomes an act of love for those people and communities with which we have a connection. Accordingly, by participating in the liturgy the family members enter into the to the mystical body of Christ who is our advocate to the Father and so participate in that sacrifice and His advocacy, on behalf of the family, too. It is the father who is the head of the family and who is called is called above the others to be in a quasi-priestly role, and is in a special position to be the advocate to God for his family. This role is executed without diminishing or replacing the advocacy of other family members.

This role of the father as advocate to the Father is a tradition that is biblical at its source, as Scott Hahn points out: ‘[In] the Book of Genesis, liturgy was the province of the Patriarchs themselves. In each household, priesthood belonged to the father, who passed the office to his son, ideally the firstborn, by pronouncing a blessing over him. In every household, fathers served as mediators between God and their families’[1] Also, just as at Mass we pray for the head of state, family members might pray for the head of the family (and by extension, to all communities and groups that we belong to).

We hear that there is a crisis of fatherhood at the moment, and for all the ways that this manifests itself in our society, one wonders if at root, part of the cause at least is the loss of this sense of advocacy for the family by one who is assigned that special role. A visible example of this aspect of fatherhood is powerful for children in learning to pray and inspiring them to do so regularly; and valuable for boys especially as a demonstration that prayer is a masculine thing to do.

The liturgical activity of the home is the liturgy of the hours because it need not be done in a church and does not need a priest participating in order to be valid, the lay office is sufficient. The ideal therefore is that the father leads the family in the liturgy of the hours, visibly and audibly. If this were to common practice, I believe it would help to reestablish prayer as something that men do and will promote a genuine, masculine fatherhood as well as encouraging vocations to the priesthood amongst boys through this masculine example of liturgical piety.

The liturgical activity of the home is the liturgy of the hours because it need not be done in a church and does not need a priest participating in order to be valid, the lay office is sufficient. The ideal therefore is that the father leads the family in the liturgy of the hours, visibly and audibly. If this were to common practice, I believe it would help to reestablish prayer as something that men do and will promote a genuine, masculine fatherhood as well as encouraging vocations to the priesthood amongst boys through this masculine example of liturgical piety.

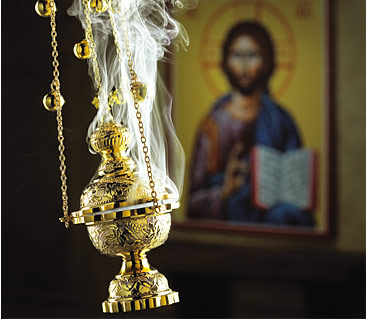

Something that would help to reinforce this is a domestic shrine. This is a visible focus in the home for prayer and the Eastern practice of creating and icon corner is particularly good for this. I will never forget seeing an Orthodox family doing their night prayers in front of the icons. The father led the prayers and all sang together or took their turn singing their prayers in the simple but robust Eastern tones. What impressed me was how all the children right down to the youngest who was four, wanted to take their turns and emulate their father. At one point two of the children argued about whose turn it was and Dad had to come in and arbitrate! They had a small incense burner burning and several long slender orange ochre beeswax candles burning in front of the icons. Each stood in reverence, facing the icon corner, occasionally crossing themselves. All the senses and faculties, it seems were directed for prayer as part of and on behalf of the family.

The families who have resolved to do this say to me that full family involvement is not always possible. It is inevitable that often family members will be too busy to join in and some will not want to. Nevertheless, the father resolved to make it clear that he was committing to regular prayer for the family and that all family members were invited at least to join in, so even if the prayer took place with only the father taking part, he was prepared to make that sacrifice on behalf of his family. And when the father is not with the family, for example if at work, he still strives to follow that liturgical rhythm of prayer and when does so, he does so on behalf of his family still.

I am only recently a father, but even when I was single and I prayed the liturgy of the hours I tried to remember to think of myself as participating in some way on behalf of my wider family and the various social groups that I am a member of, including work. Through my personal relationships, and this is still the case, those groups are present in the liturgy, to some degree, when I am. It is one way I can emulate Our Lord by participating in His sacrifice, and make a sacrifice for those with whom I relate. My hope is that will play a small part in bringing God's grace into these groups of people so that they might become communities supernaturally bound together in love. In my prayers, every morning, I consciously dedicate my liturgical activity to all those groups and with whom I am connected so I think of myself as representing my family, my friends, my work, the Church, social groups and so on, perhaps naming any individuals that are on my mind at that time. if, during the day I am not in a position to recite an hour, which can be often, I try mentally to mark the hour with a small prayer to maintain that sense of rhythm.

Images: top two are both paintings of the Holy Family by Giuseppe Crespi painting around the 1700; below: the Nativity with God the Father and the Holy Ghost by Giambattista Pittoni, Italian, 17th century

[1] Scott Hahn, Letter and Spirit, pub DLT, p28

A Beautiful Pattern of Prayer - the Path to Heaven is a Triple Helix…

...And it passes through an octagonal portal.

...And it passes through an octagonal portal.

Liturgy, the formal worship of the Church - the Mass and the Liturgy of the Hours, the Eucharist at its centre - is the ‘source and summit of Christian life’. We are made by God to be united with him in heaven in a state of perfect and perpetual bliss, a perfect exchange of love. All the saints in heaven are experiencing this and liturgy is what they do. It is what we all are made to do; this how it is the summit of human existence. Our earthly liturgy is a supernatural step into the heavenly liturgy, this unchanging yet dynamic heavenly drama of love between God and the saints; and the node, the point at which all of the cosmos is in contact with the supernatural is Christ, present in the Eucharist. It is more fantastic than anything ever imagined in a sci-fi drama. There is no need to watch Dr Who to see a space-time vortex, when I take communion at Mass (assuming I am in the proper state of grace) I pass through one. And there’s no worry about hostile aliens, that battle is fought and won.

Everything else that the Church offers and that we do is meant to deepen and intensify our participation in this mystery. Through the participation in the liturgy, we pass from the temporal into a domain that is outside time and space. Heaven is a mode of existence where all time, past and future is compressed into single present moment; and all places are present at a single point.

Our participation in this cannot be perfect in this life, bound as we are by the constraints of time and space. We must leave the church building to attend to the everyday needs of life. However, this does not, in principle, mean that we cannot pray continuously. The liturgy is not just the summit of human existence; it is the source of grace by which we reach that summit. In conforming to the patterns and rhythms of the earthly liturgy in our prayer, we receive grace sufficient to sanctify and order all that we do, so that we are led onto the heavenly path and we lead a happy and joyous life. This is also the greatest source of inspiration and creativity we have. We will get thoughts and ideas to help us in choices that we make at every level and which permeate every action we take. Then our mundane lives will be the most productive and fulfilling they can be.

How do we know what these liturgical patterns are? We take our cue from nature, or from scripture. Creation bears the thumbprint of the Creator and through its beauty it directs our praise to God and opens us to His grace. The patterns and symmetry, grasped when we recognize its beauty, are a manifestation of the divine order.

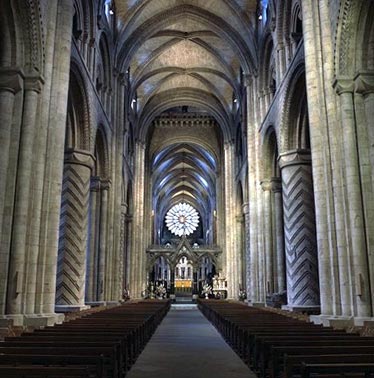

Traditional Christian cosmology is the study of the patterns and rhythms of the planets and the stars with the intention of ordering our work and praise to the work and praise of the saints in heaven. This heavenly praise is referred to as the heavenly liturgy. The liturgy that we participate, which is connected supernaturally to the heavenly liturgy is called the earthly liturgy. The liturgical year of the Church is based upon these natural cycles of the cosmos. By ordering our worship to the cosmos, we order it to heaven. The date of Easter, for example, is calculated according to the phases of the moon. The earthly liturgy, and for that matter all Christian prayer, cannot be understood without grasping its harmony with the heavenly dynamic and the cosmos. In order to help us grasp this idea that we are participating in something much bigger that what we see in the church when we go to Mass, the earthly liturgy should evoke a sense of the non-sensible aspect of the liturgy through its dignity and beauty and especially the beauty and solemnit of the art and music we use with it. All our activities within it: kneeling, praying, standing, should be in accordance with the heavenly standard; the architecture of the church building, and the art and music used should all point us to what lies beyond it and give us a real sense that we are praising God with all of his creation and with the saints and angels in heaven. When we pray in accordance with these patterns we are opening ourselves up to God’s helping hand at just the moment when it is offered. This is the prayer that places us in directly in beam of the heat lamp of God’s grace.

The harmony and symmetry of the heavenly order can be expressed numerically. For example, because of the seven days of creation in Genesis there are seven days in the week (corresponding also to a half phase of the idealised lunar cycle). The Sunday mass is the summit of the weekly cycle. In the weekly cycle there is in addition day, the so-called eighth ‘day’ of creation, which symbolises the new order ushered in by the incarnation, passion, death and resurrection of Christ. Sunday the day of his resurrection, is simultaneously the eighth and first day of the week (source and summit). Eight, expressed as ‘7 + 1’ is a strong governing factor in the Church’s earthly liturgy. (It is why baptismal fonts and baptistries are constructed in an octagonal shape and why you might have octagonal patterns on a sanctuary floors.)

The harmony and symmetry of the heavenly order can be expressed numerically. For example, because of the seven days of creation in Genesis there are seven days in the week (corresponding also to a half phase of the idealised lunar cycle). The Sunday mass is the summit of the weekly cycle. In the weekly cycle there is in addition day, the so-called eighth ‘day’ of creation, which symbolises the new order ushered in by the incarnation, passion, death and resurrection of Christ. Sunday the day of his resurrection, is simultaneously the eighth and first day of the week (source and summit). Eight, expressed as ‘7 + 1’ is a strong governing factor in the Church’s earthly liturgy. (It is why baptismal fonts and baptistries are constructed in an octagonal shape and why you might have octagonal patterns on a sanctuary floors.)

Without Christ, the passage of time could be represented by a self enclosed weekly cycle sitting in a plane. The eighth day represents a vector shift at 90° to the plane of the circle that operates in combination with the first day of the new week. The result can be thought of as a helix. For every seven steps in the horizontal plane, there is one in the vertical. It demonstrates in earthly terms that a new dimension is accessed through each cycle of our participation temporal liturgical seven-day week.

The 7+1 form operates in the daily cycle of prayer in the Divine Office too. Quoting Psalm 118, St Benedict incorporates into his monastic rule the seven daily Offices of Lauds, Prime, Tierce, Sext, None, Vespers, and Compline; plus an eighth, the night or early-morning Office, Matins.

The 7+1 form operates in the daily cycle of prayer in the Divine Office too. Quoting Psalm 118, St Benedict incorporates into his monastic rule the seven daily Offices of Lauds, Prime, Tierce, Sext, None, Vespers, and Compline; plus an eighth, the night or early-morning Office, Matins.

Prime has since been abolished in the Roman Rite, but usually the 7+1 repetition is maintained by having daily Mass (not common in St Benedict’s time). Eight appears in the liturgy also in the octaves, the eight-day observances, for example of Easter. Easter is the event that causes the equivalent vector shift, much magnified, in the annual cycle. The Easter Octave is eight solemnities – eight consecutive eighth days that starts with Easter Sunday and finishes the following Sunday.

These three helical paths run concurrently, the daily helix sitting on the broader weekly helix which sits on the yet broader annual helix. We are riding on a roller coaster triple corkscrewing its way to heaven. This, however, is a roller coaster that engenders peace.

For those who are not aware of this, more information on this topic and how to conform you're life to this pattern, read The Little Oratory; A Beginner's Guide to Prayer in the Home and especially the section, A Beautiful Pattern of Prayer.

Pictures: The baptismal font, top, is 11th century, from Magdeburg cathedral. The floor patterns are from the cathedral at Monreale, in Sicily and from the 12th century. The building is the 13th century octagonal baptistry in Cremona, Italy.

How to Make an Icon Corner

Beauty calls us to itself and then beyond, to the source of all beauty, God. God's creation is beautiful, and God made us to apprehend it so that we might see Him through it. The choice of images for our prayer, therefore, is important. Beautiful sacred imagery not only aids the process of prayer, but what we pray with influences profoundly our taste: praying with beautiful sacred art is the most powerful education in beauty that there is. In the end this is how we shape our culture, especially so when this is rooted in family prayer. The icon corner will help us to do that. I am using icon here in the broadest sense of the term, referring to a sacred image that depicts the likeness of the person portrayed. So one could as easily choose Byzantine, gothic or even baroque styles.

The contemplation of sacred imagery is rooted in man’s nature. This was made clear by the 7th Ecumenical Council, at Nicea. Through the veneration icons, our imagination takes us to the person depicted. The veneration of icons, therefore, is an aid to prayer first and it serves to stimulate and purify the imagination. This is discussed in the writings of Theodore the Studite (759-826AD), who was one of the main theologians who contributed to the resolution of the iconoclastic controversy.

Beauty calls us to itself and then beyond, to the source of all beauty, God. God's creation is beautiful, and God made us to apprehend it so that we might see Him through it. The choice of images for our prayer, therefore, is important. Beautiful sacred imagery not only aids the process of prayer, but what we pray with influences profoundly our taste: praying with beautiful sacred art is the most powerful education in beauty that there is. In the end this is how we shape our culture, especially so when this is rooted in family prayer. The icon corner will help us to do that. I am using icon here in the broadest sense of the term, referring to a sacred image that depicts the likeness of the person portrayed. So one could as easily choose Byzantine, gothic or even baroque styles.

The contemplation of sacred imagery is rooted in man’s nature. This was made clear by the 7th Ecumenical Council, at Nicea. Through the veneration icons, our imagination takes us to the person depicted. The veneration of icons, therefore, is an aid to prayer first and it serves to stimulate and purify the imagination. This is discussed in the writings of Theodore the Studite (759-826AD), who was one of the main theologians who contributed to the resolution of the iconoclastic controversy.

In emphasising the importance of praying with sacred images Theodore said: “Imprint Christ…onto your heart, where he [already] dwells; whether you read a book about him, or behold him in an image, may he inspire your thoughts, as you come to know him twofold through the twofold experience of your senses. Thus you will see with your eyes what you have learned through the words you have heard. He who in this way hears and sees will fill his entire being with the praise of God.” [quoted by Cardinal Schonborn, p232, God’s Human Face, pub. Ignatius.]

It is good, therefore for us to develop the habit of praying with visual imagery and this can start at home. The tradition is to have a corner in which images are placed. This image or icon corner is the place to which we turn, when we pray. When this is done at home it will help bind the family in common prayer.

![]() Accordingly, the Catechism of the Catholic Church recommends that we consider appropriate places for personal prayer: ‘For personal prayer this can be a prayer corner with the sacred scriptures and icons, in order to be there, in secret, before our Father. In a Christian family kind of little oratory fosters prayer in common.’(CCC, 2691)

Accordingly, the Catechism of the Catholic Church recommends that we consider appropriate places for personal prayer: ‘For personal prayer this can be a prayer corner with the sacred scriptures and icons, in order to be there, in secret, before our Father. In a Christian family kind of little oratory fosters prayer in common.’(CCC, 2691)

I would go further and suggest that if the father leads the prayer, acting as head of the domestic church, as Christ is head of the Church, which is His mystical body, it will help to re-establish a true sense of fatherhood and masculinity. It might also, I suggest, encourage also vocations to the priesthood.

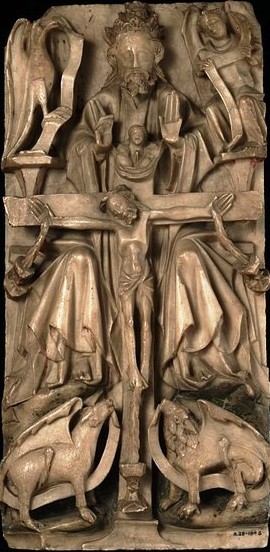

The placement should be so that the person praying is facing east. The sun rises in the east. Our praying towards the east symbolizes our expectation of the coming of the Son, symbolized by the rising sun. This is why churches are traditionally ‘oriented’ towards the orient, the east. To reinforce this symbolism, it is appropriate to light candles at times of prayer. The tradition is to mark this direction with a cross. It is important that the cross is not empty, but that Christ is on it. in the corner there should be representation of both the suffering Christ and Christ in glory.

‘At the core of the icon corner are the images of the Christ suffering on the cross, Christ in glory and the Mother of God. An excellent example of an image of Christ in glory which is in the Western tradition and appropriate to the family is the Sacred Heart (the one from Thomas More College's chapel, in New Hampshire, is shown). From this core imagery, there can be additions that change to reflect the seasons and feast days. This way it becomes a timepiece that reflects the cycles of sacred time. The “instruments” of daily prayer should be available: the Sacred Scriptures, the Psalter, or other prayer books that one might need, a rosary for example.

This harmony of prayer, love and beauty is bound up in the family. And the link between family (the basic building block upon which our society is built) and the culture is similarly profound. Just as beautiful sacred art nourishes the prayer that binds families together in love, to each other and to God; so the families that pray well will naturally seek or even create art (and by extension all aspects of the culture) that is in accord with that prayer. The family is the basis of culture.

Confucius said: ‘If there is harmony in the heart, there will be harmony in the family. If there is harmony in the family, there will be harmony in the nation. If there is harmony in the nation, there will be harmony in the world.’ What Confucius did not know is that the basis of that harmony is prayer modelled on Christ, who is perfect beauty and perfect love. That prayer is the liturgical prayer of the Church.

A 19th century painting of a Russian icon corner

How to Pray With Visual Imagery

It is now more than three and a half years since I started this blog so first of all I would like to thank so many of you for your interest and your comments. I am currently involved in several book projects which will be published in the early part of next year - more information to come. In order to give myself time to write these, I thought I would reduce my postings to one fresh piece per week. However, it also occurred to me that many of you who read this, will not have seen much of what I posted in the first two years. In my mind, these are foundational to my thinking and shed light on much of what I write now, so I thought they would be worth repeating. So for these two reasons I thought I would replay some of these foundational posts. So for the next couple of months, I will alternate old and new. The first replay was first published in April, 2010:

When I first started painting icons I was, of course, interested in knowing as well how they related to prayer. I was referred by others (though not my icon painting teacher) to books that were intended as instruction manuals in visual prayer. I read a couple and perhaps I chose badly, but I struggled with them. One the one hand, they seemed to be suggesting some sort of meditative process in which one spent long quiet periods staring at an icon and experiencing it, so to speak, allowing thoughts and feelings to occur to me. Being by nature an Englishman of the stiff-upper-lip temperament (and happy to be so) I was suspicious of this. I had finally found a traditional method of teaching art that didn’t rely on splashing my emotions on paper, and here I was being told that in the end, the art I was learning to produce was in fact intended to speak to us through a heightened language of emotion. Furthermore, the language used to articulate the methods always seemed to employ what struck me as pseudo-mystical expressions and which, I suspected, were being used to hide the fact that they weren’t really saying very much.

When I first started painting icons I was, of course, interested in knowing as well how they related to prayer. I was referred by others (though not my icon painting teacher) to books that were intended as instruction manuals in visual prayer. I read a couple and perhaps I chose badly, but I struggled with them. One the one hand, they seemed to be suggesting some sort of meditative process in which one spent long quiet periods staring at an icon and experiencing it, so to speak, allowing thoughts and feelings to occur to me. Being by nature an Englishman of the stiff-upper-lip temperament (and happy to be so) I was suspicious of this. I had finally found a traditional method of teaching art that didn’t rely on splashing my emotions on paper, and here I was being told that in the end, the art I was learning to produce was in fact intended to speak to us through a heightened language of emotion. Furthermore, the language used to articulate the methods always seemed to employ what struck me as pseudo-mystical expressions and which, I suspected, were being used to hide the fact that they weren’t really saying very much.

So I started to ask my teacher about this and to observe Eastern Christians praying with icons. What struck me was that prayer for them seemed to be pretty much what prayer was for me. They said prayers that contained the sentiments that they wished to express to God. The difference between what they did and what I did at that time was that they turned and looked at an icon as they prayed. Also, when at home, often happily and without embarrassment they sang their prayers using very simple, easily learnt chant. Before meals, for example, the family would stand up, face an icon of Christ on the wall and sing a prayer of gratitude or even just the Our Father.

As I learnt more about icons through learning to paint them, I realized that every aspect of the style of an icon is worked out to engage us in a dynamic that assists prayer – through its form and content the icon will do the work of directing our thoughts to heaven. In short I don’t need to ‘do’ anything. The icon does the work for me.

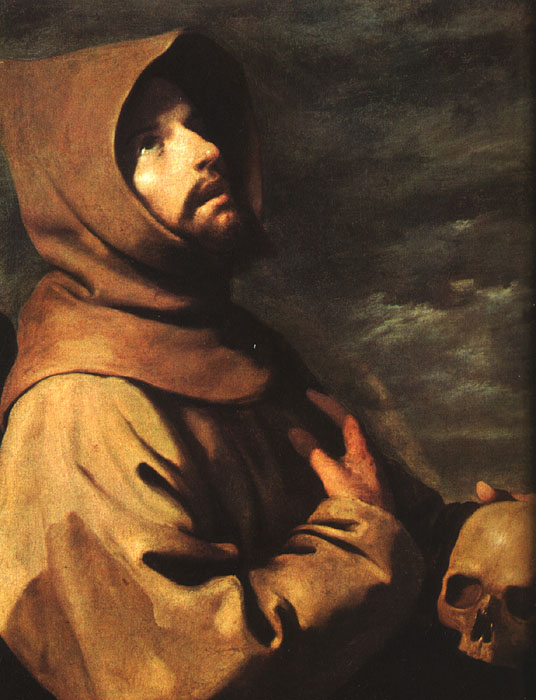

The iconographic form is not the only one to do this. The Western Catholic tradition is very rich and has also the Baroque and gothic art forms that are carefully worked out to engage the observer in a dynamic of prayer, although in different ways. If the icon draws our thoughts to heaven, the baroque form is designed in contrast to have an impact at a distance in order to make God present on earth. The gothic figurative art is the art of pilgrimage, or of transition from earth to heaven, and stylistically it sits between the iconographic and baroque. It is the ‘gradual psalm’ of artistic form. Just like the spires of its architecture, it spans the gap between heaven and earth so that we have a sense both of where we going to and where we are coming from. I will discuss how the form of each tradition achieves in the next articles I write.

So the advice I was given was to ditch the books about praying with icons, and learn first to pray. Then as I pray always aim to have visual imagery that I allow to engage my sight and which assists. St Augustine said that those who sing their prayers pray twice. I would add that those who look at visual imagery as well pray three times (and if we use incense four times, and consider posture five). This process of engaging different aspects of the person in addition to the intellect is a move towards the ideal of praying with the whole person. This is what praying from the heart means. The heart is the vector sum of our thoughts and actions. It is our human centre of gravity when both body and soul are considered. It is the single point that, when everything is taken into account, defines what I am doing. It is the heart of us, in the sense of representing the core. This is why it is a symbol of the person. It is a symbol of love also because each of us is made by God to love him and our fellow man. It symbolizes what we ought to be rather than, necessarily, what we are. The modern world has distorted the symbolism of the heart into one of desire and ‘heartfelt’ emotion, precisely because these are the qualities that so many today associate with the essence of humanity.

The liturgy is ultimate form of prayer. By praying with the Church, the mystical body of Christ, we are participating in ‘Christ's own prayer addressed to the Father in the Holy Spirit. In the liturgy, all Christian prayer finds its source and goal.’[1] Therefore, the most important practice of praying with visual imagery is in the context of the liturgy. For example, when we pray to the Father then we look at Christ, for those who have seen Him have seen the Father. The three Catholic figurative traditions in art already mentioned were developed specifically to assist this process.

Just as the liturgy is the ‘source and goal’ of prayer, so liturgical art is, I would argue, the source and goal of all Catholic art. The forms that are united to the liturgy are the basis of Catholic culture. All truly Catholic art will participate in these forms and so even if a landscape in the sitting room, will point us to the liturgical. We cannot become a culture of beauty until we habitually engage in the full human experience of the liturgy. In the context of visual art, this practice will be the source of grace from which artists will be able to produce art that will be the basis of the culture of beauty; the source of grace and from which patrons will know what art to commission; and in turn by which all of us will be able to fulfill our vocation, whatever it may be, by travelling on the via pulchritudinis, the Way of Beauty, recently described by Pope Benedict XVI.

Of course, each individual (depending upon his purse) usually has a limited influence on what art we see in our churches. However, as lay people, we can pray the Liturgy of the Hours and control imagery that we use. The tradition of the prayer corner, in which paintings are placed on a small table or shelf at home as a focus of prayer, is a good one to adopt. We ‘orientate’ our prayer towards this, letting the imagery engage our sight as we do so. We can also sing, use incense and stand, bow, sit or kneel as appropriate while praying. A book I found useful in this regard, which describes traditional practices is called Earthen Vessels (The Practice of Personal Prayer According to the Patristic Tradition) by Gabriel Bunge, OSB

Does this mean that meditation of visual imagery is not appropriate? No it does not. But as with all prayer that is not liturgical, it is should be understood by its relation to the liturgy. So just as lectio divina, for example, is good in that it is ordered to the liturgy because through it our participation in the liturgy is deepened and intensified. So, perhaps, should meditation upon visual imagery should be understood in relation to the use of imagery in the liturgical context. Also, I would say that it is useful, just as with lectio, to avoid the confusion between the Western and Eastern non-Christian ideas of meditation and contemplation are. I was recommended a book recently that helped me greatly in this regard. It is called Praying Scripture for a Change – An Introduction to Lectio Divina by Dr Tim Gray.

[1] CCC, 1073

Thomas Aquinas on the Psalms and the Liturgy as the Source of Wisdom

Educators take note! Here is the greatest source of wisdom. When writing about Jean Leclercq's Love of Learning and the Desire for God, I referred to his description of the tension that exists between the different educational approaches of the scholastic and the monastics schools . The former characterised (in part) by relying of very dry, technical language of logic; the latter relying on more accessible language that draws on sources such as scripture more directly, which while more poetic and beautiful might be criticised for lacking precision). As Leclercq points out, when the spiritual life of the person is centred on the liturgy, then either form of education can open the door to full knowledge, in love and through God's grace. The liturgy is the place where all of this can be synthesized and one is immersed in God’s wisdom and this, deep in the heart of the person, is where we form the culture.

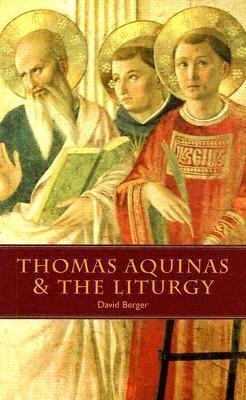

St Thomas is the first name who comes to mind when one thinks of scholastics so his attitude to the liturgy would be of interest in this regard. In his little book Thomas Aquinas and the Liturgy, David Berger directs us to Thomas's special regard for the psalms and in the Divine Office as source of grace and wisdom, which reinforces the point that Leclerqc made. This regard for the psalms arises because Thomas considered that within the single book of the psalms they contain the entire content of theology. Berger refers us to his commentary on the psalms where Thomas says the following: 'The material is universal for while the particular books of the Canon of Scripture contain special materials, this book has the general material of Theology as a whole.' Then in referring to their special place in the liturgy where they are to be sung he says: 'This is what Dionysius [the Areopagite] says in Book 3 of the Celestial Hierarchy, the sacred scripture of the Divine Songs (Psalms) is intended to sing of all sacred and divine workings.' St Thomas goes on to tell us that these are presented in the most dignified form - liturgical praise, thanksgiving and prayer. And according to St Thomas, says Berger, 'wherever theology reverts to the psalms it shows it's character of wisdom in a special way'

Educators take note! Here is the greatest source of wisdom. When writing about Jean Leclercq's Love of Learning and the Desire for God, I referred to his description of the tension that exists between the different educational approaches of the scholastic and the monastics schools . The former characterised (in part) by relying of very dry, technical language of logic; the latter relying on more accessible language that draws on sources such as scripture more directly, which while more poetic and beautiful might be criticised for lacking precision). As Leclercq points out, when the spiritual life of the person is centred on the liturgy, then either form of education can open the door to full knowledge, in love and through God's grace. The liturgy is the place where all of this can be synthesized and one is immersed in God’s wisdom and this, deep in the heart of the person, is where we form the culture.

St Thomas is the first name who comes to mind when one thinks of scholastics so his attitude to the liturgy would be of interest in this regard. In his little book Thomas Aquinas and the Liturgy, David Berger directs us to Thomas's special regard for the psalms and in the Divine Office as source of grace and wisdom, which reinforces the point that Leclerqc made. This regard for the psalms arises because Thomas considered that within the single book of the psalms they contain the entire content of theology. Berger refers us to his commentary on the psalms where Thomas says the following: 'The material is universal for while the particular books of the Canon of Scripture contain special materials, this book has the general material of Theology as a whole.' Then in referring to their special place in the liturgy where they are to be sung he says: 'This is what Dionysius [the Areopagite] says in Book 3 of the Celestial Hierarchy, the sacred scripture of the Divine Songs (Psalms) is intended to sing of all sacred and divine workings.' St Thomas goes on to tell us that these are presented in the most dignified form - liturgical praise, thanksgiving and prayer. And according to St Thomas, says Berger, 'wherever theology reverts to the psalms it shows it's character of wisdom in a special way'

Then referring to Aquinas's early education as a Benedictine at Monte Cassino, Berger says: 'The love of singing the psalms in the context of the divine office, founded in Monte Cassino, seems to have stayed alive in Thomas all his life. The best known of Thomas's early biographers, William of Tocco, who had the privilege of knowing Thomas personally, reports that he would arise at night before the actual hour of Mattins.' (p14)

If wisdom is the goal of education, this reinforces the idea that the liturgy, including the liturgy of the hours, should be at the heart of the life of an educational institution, and that students should be encouraged to understand the value of this in helping them to achieve their goal. It is not simply that it is the whole psalter is sung in liturgy, but that the liturgy itself prepares us to receive and accept the wisdom contained within them in a special way.

One hopes that it is having the same effect on me as it has on St Thomas, even if only partially!

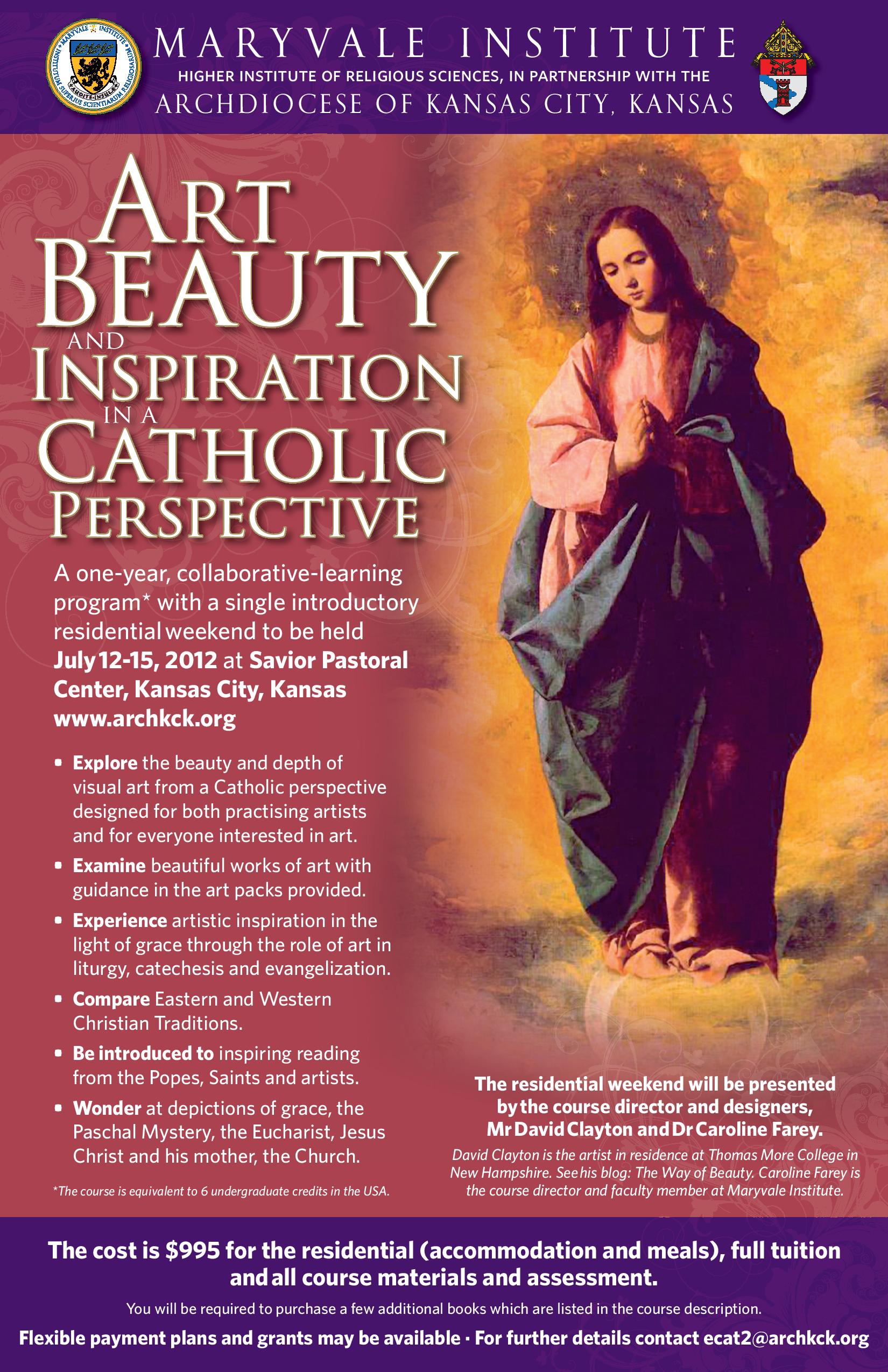

Plus don't forget to tell your friends about the course on art and beauty this summer.....

Send Out the L-Team - Making a Sacrifice of Praise for American Veterans

Recently when I went home to England we had a reunion of old college friends of mine. Most were not believers of any sort - I had known them since I was eighteen and so the friendships pre-date, by a long way, my conversion (I was 31 when was received into the Church and have just turned 50 fyi). It was great to catch up with everyone and see how they were getting on. I was interested by a recent decision of one. She had given up teaching genetics at Imperial College, London and was now working for a company that would go into investment banks in the City and teach executives how to meditate to help them deal with the stress of the job. She been introduced to meditation when she took up yoga for the physical benefits and then was attracted to the 'spirituality' that is attached to it. In order to convince the executives that there is something to this Eastern meditation, they would be armed with statistics from scientific research. She said that there had been observable improvements in the condition of heart patients in hospitals when people meditated. The research shows, she said, that even if the patients did not meditate with the visitors or even if they were unaware it was happening, just have meditation going on in the building seemed to have a positive effect.

I was happy to believe that she was right and that the research backed her up. However, my reaction was that if anything good was coming out of this, then it was because it was participating in some way in Christian prayer, whether they knew it or not. I would contest that the fullness of what they are doing is in the traditional prayer of the Church and there is every chance that this would be even more powerful if done.

When I got back to the US I contacted local hospitals and asked if they would like a small group of people to come and sing Vespers on a regular basis. What is surprising and some ways dismaying, is that I couldn't find anyone who had ever heard of this being done before. There are Christian prayer groups who visit hospitals, but I don't hear of people making regular commitment (beyond the occasional concert) to pray the liturgy. Shouldn't the liturgy of the hours be one of our most powerful weapons as part of the New Evangelisation?

I didn't expect anyone to welcome us with open arms. All I wanted was for us to be tolerated, so that we could pray the Office for them. If nobody wanted to come we didn't mind, we wanted to pray for them regardless. The point in my mind was to make the personal sacrifice in prayer, praying for the well being of the patients and for the hospital as a community. Having said that, we would make every effort to chant beautifully for God regardless of how many others attend.

I was delighted when the Catholic chaplain at the VA Hospital, the American armed services veterans hospital in Manchester, New Hampshire, invited us to come in every other Monday evening. Fr Boucher is an old friend of mine and the college. Since September, myself and Dr Tom Larson from Thomas More College have been leading a group of male students in Vespers and Compline on Monday evenings. Because we were singing the psalms, we have presented it as ecumenical and administratively this enabled us to fill an available slot in the chapel and it has attracted a few non-Catholics

The veterans at the hospital know that we are there but very few have been able to come each time. Most are too ill or injured even to be able to get up one floor from the ward without someone dressing them and bringing them up and those helpers aren't always available. Even then, I am not fooling myself that large numbers want to come but can't make it. This is an unusual thing. But we are undaunted. A regular group of up to a dozen guys has been going in and singing the psalms. We keep the door open and sing loud enough so that it floats down the corridor for the wards to hear. They are always surprised at the effort we make to sing well on their behalf and in order to praise God. It has been gratifying to hear how readily those who come, many who have never been to any Office before, can sing with us, and want to. We are singing in the vernacular so that any visitor can understand and join in. Nevertheless the tones are modal and have the feel of the plainchant tradition and this I think draws them in. (They were developed for the liturgy at the college).

I am not usually the sort for public prayer. I wouldn't go out and sing in public, in this way if I didn't feel that we have is is beautiful and accessible and fits naturally with the language I have done processions in public before, cringing with embarrassment at the songs we are singing and having to offer it up as a penance in order to keep doing it. Unlike those, I am happy to sing these in a in the range that is natural to me. They feel vigorous and masculine, yet pious and respectful of God, so we hope promoting the right internal disposition. We are doing this for soldiers after all.

For any who are interested we did some very recordings of what we have been singing (the recordings below). Some are in unison and some are harmonised.

Although I would love to see this tested, I can't comment on whether or not it measurably reduces the stress levels of heart patients, but regardless I am happy that this is benefitting these people and this community in ways that cannot be measured. I make the point to the students who come along, that one thing we can be certain of is that this is a sacrifice that is worth making. We jokingly call ourselves a crack squad from the 'L-team' (L for liturgy!)

I would like to finish by acknowedging how gracious and positive the hospital staff and the priests and ministers of various denominations at the hospital have been towards us, in allowing us to come and offering personal encouragment.

Here is the Our Father we sang (which was originally composed by Paul Jernberg, Thomas More College's Composer in Residence for his St Philip Neri Mass)

http://youtu.be/UC8kqYYbJEc

...and the Magnificat sang:

http://youtu.be/oElTV1jogS8

as you listen to these, try to remember they are not professional recordings. They are recorded on a cell phone by a group of amateurs. One of the great things about Paul's arrangements is that someone who sings as badly as me can learn my part and sing it.

Praying the Divine Office on Holiday When You Haven't Got Your Breviary With You

How do you pray the Liturgy of the Hours when the books are too heavy to put into your suitcase and your normal routine is disrupted? I have just returned from a visit to England and Spain to see my family. For various reasons I haven't been able to leave the US for a couple of years. I couldn't wait to see everyone again and I had a great time. Lots of time spent with family and friends, walks in the countryside in both countries, visits to English gardens and even a pilgrimage site in North Wales. There was plenty to report on and I will be writing about it in the coming weeks.

First though, how to keep going with the prayer routine while travelling? The quickest answer is to use your smart phone and access the Office online. This was too expensive for me when going to Europe, so I had to go low-tech. Furthermore, not everyone has a smart phone even in the US, so for many this is never an option. The books for the Divine Office are bulky for travel - the time I was away was the transition from volume II to volume III in my three volume briviary, so I would need both. And if you are as careless as I am there is always the worry about the expense of replacing them if I lose them. (I can lose anything that isn't attached to me - I left the first book of Hours given to me by my spiritual director on a plane.) I could have taken the Shorter Morning and Evening Prayer, but this would still leave me with the problem of what to do for the minor Offices.

How do you pray the Liturgy of the Hours when the books are too heavy to put into your suitcase and your normal routine is disrupted? I have just returned from a visit to England and Spain to see my family. For various reasons I haven't been able to leave the US for a couple of years. I couldn't wait to see everyone again and I had a great time. Lots of time spent with family and friends, walks in the countryside in both countries, visits to English gardens and even a pilgrimage site in North Wales. There was plenty to report on and I will be writing about it in the coming weeks.

First though, how to keep going with the prayer routine while travelling? The quickest answer is to use your smart phone and access the Office online. This was too expensive for me when going to Europe, so I had to go low-tech. Furthermore, not everyone has a smart phone even in the US, so for many this is never an option. The books for the Divine Office are bulky for travel - the time I was away was the transition from volume II to volume III in my three volume briviary, so I would need both. And if you are as careless as I am there is always the worry about the expense of replacing them if I lose them. (I can lose anything that isn't attached to me - I left the first book of Hours given to me by my spiritual director on a plane.) I could have taken the Shorter Morning and Evening Prayer, but this would still leave me with the problem of what to do for the minor Offices.

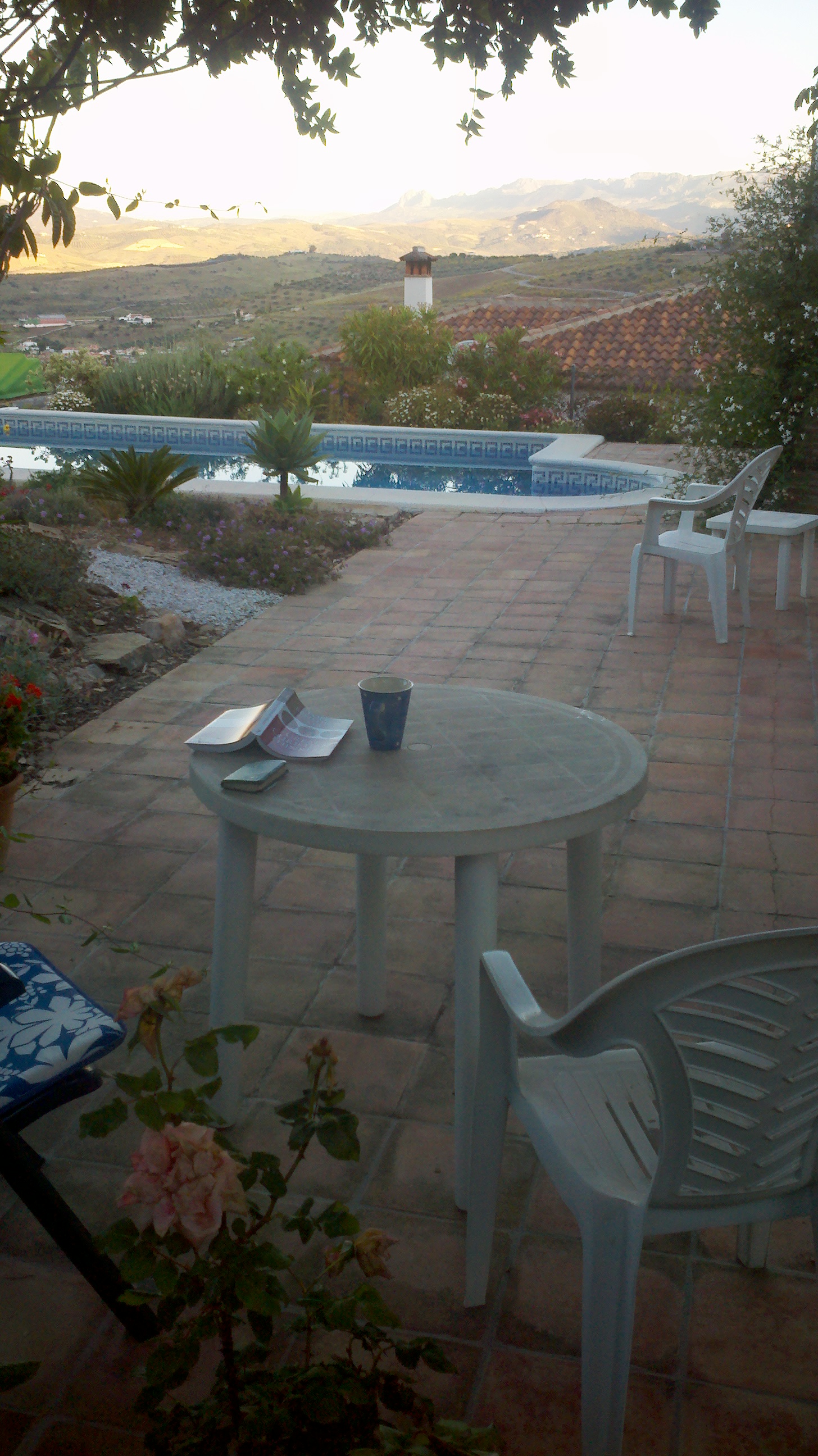

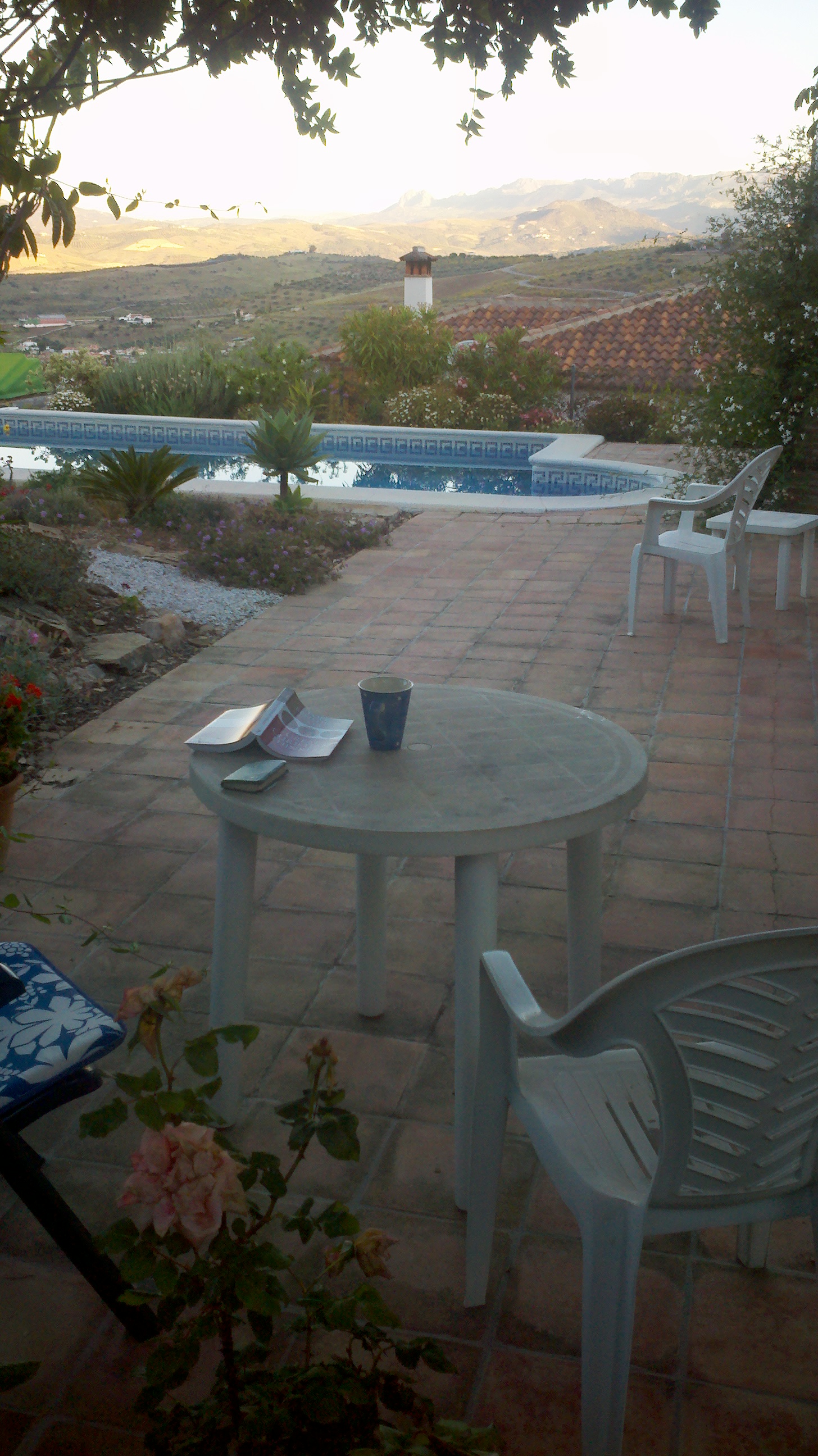

Here's what I did. In his book Earthen Vessels published by Ignatius Press, Gabriel Bunge OSB explains that the essence of the Liturgy of the Hours is marking the Hours and saying the psalms. As a lay person I am not bound to the weekly cycle of the psalms as set out by St Benedict, or the four-weekly cycle that secular priests are bound to. I can devise any cycle of the psalms that suits me and pray them at the hours and this still constitutes liturgical prayer and if I follow it I will still be praying with the Church. I happened to have with me a tiny edition of the New Testament with the Psalms so I made us of this. At each Hour I read the next psalm (or two or even three if they were short) in the order that they come in the bible, 1- 150. I did start with Psalm 94 each day, the invitatory psalm, and where I knew there were penitential psalms (eg psalm 50), I tried to save them for Friday. At the Hours of Lauds, Vespers and Compline, I delved into the gospels and sang the Benedictus, the Magnifcat and the Nunc Dimittis all from Luke. I have included some photos of my little chapel on the patio at my parents' place in Spain. They have a great view and their garden is lovely, so the motivation to sit out their with a pot of coffee and the psalms was great!

Here's what I did. In his book Earthen Vessels published by Ignatius Press, Gabriel Bunge OSB explains that the essence of the Liturgy of the Hours is marking the Hours and saying the psalms. As a lay person I am not bound to the weekly cycle of the psalms as set out by St Benedict, or the four-weekly cycle that secular priests are bound to. I can devise any cycle of the psalms that suits me and pray them at the hours and this still constitutes liturgical prayer and if I follow it I will still be praying with the Church. I happened to have with me a tiny edition of the New Testament with the Psalms so I made us of this. At each Hour I read the next psalm (or two or even three if they were short) in the order that they come in the bible, 1- 150. I did start with Psalm 94 each day, the invitatory psalm, and where I knew there were penitential psalms (eg psalm 50), I tried to save them for Friday. At the Hours of Lauds, Vespers and Compline, I delved into the gospels and sang the Benedictus, the Magnifcat and the Nunc Dimittis all from Luke. I have included some photos of my little chapel on the patio at my parents' place in Spain. They have a great view and their garden is lovely, so the motivation to sit out their with a pot of coffee and the psalms was great!

We have been developing psalm tones at for English for use at Thomas More College. These are designed so that any tone can be applied to any psalm. I apply the inflexions in the melody to the natural emphases in the text. This meant that even with just two or three simple tones sticking in my memory, I could sing the whole Office if I wanted to. This is did if I thought I was out of earshot. I am not yet at the level of evangelical fervour to be able to sing the psalms solo in a busy  shopping mall (although I am getting there - I am much less self conscious about singing in front of others than I used to be). The great thing about working from such a small book is that I could fit it in my back pocket and during the course of the day, wherever I happened to be, could pull it out and read the next psalm.

shopping mall (although I am getting there - I am much less self conscious about singing in front of others than I used to be). The great thing about working from such a small book is that I could fit it in my back pocket and during the course of the day, wherever I happened to be, could pull it out and read the next psalm.

For the Vigils (the Office of Readings) I would always read a passage from the New Testament. The Office of Readings also includes each day a reading from the works of the Church Fathers. By chance, for my holiday reading I had with me the collected addresses (70 0f them) by Pope Benedict XVI on the Church Fathers called Great Christian Thinkers, From the Early Church through to the Middle Ages and so I read one of these each day. Incidentally this is a wonderful survey of the mystical and theological writings of the great figures of the Church. If anyone is interested in a guide for reading the Fathers, this is the place to start.

I was also in a position to supplement this with mental prayer and so each day did in addition to this some lection divina. I did a short series of articles on how I was instructed to pratise this ancient form of prayer, here.

If I went for a walk in the hills (we about 45 minutes from Malaga in southern Spain) then my little bible was so small that I could fit it in my back pocket and at a convenient place pull it out and sing the psalms to the plants and any passing mountain deer. I picked a rock among the wild flowers to sit on...

in position where there was a pleasant view of the of Spanish farmland, and began.

Glory be to God for dappled things...!

Praying the Mass and the Liturgy of the Hours teaches us how to discerning God's will

Liturgical prayer is a means for discerning our personal vocation and God’s will for us…and so much more In the Lenten readings from the Liturgy of the Hours we have an example how through the Liturgy the Church instructs us about the value of praying the Liturgy with the Church. The reading from Vespers on Monday of weeks 1 and 2 in Lent reads:

‘My brothers, I implore you by God’s mercy to offer your very selves to him: a living sacrifice, dedicated and fit for his acceptance, the worship offered by mind and heart. Adapt yourselves no longer to the pattern of this present world, but let your minds be remade and your whole nature thus transformed. Then you will be able to discern the will of God, and to know what is good, acceptable and perfect.’ (Rom 12:1-2)

Liturgical prayer is a means for discerning our personal vocation and God’s will for us…and so much more In the Lenten readings from the Liturgy of the Hours we have an example how through the Liturgy the Church instructs us about the value of praying the Liturgy with the Church. The reading from Vespers on Monday of weeks 1 and 2 in Lent reads:

‘My brothers, I implore you by God’s mercy to offer your very selves to him: a living sacrifice, dedicated and fit for his acceptance, the worship offered by mind and heart. Adapt yourselves no longer to the pattern of this present world, but let your minds be remade and your whole nature thus transformed. Then you will be able to discern the will of God, and to know what is good, acceptable and perfect.’ (Rom 12:1-2)

This passage is telling us in order to discern the will of God, we ought to make a ‘living sacrifice’ of ourselves. That living sacrifice is specifically our worship of God, that is, our participation in the liturgy - the Mass and the Liturgy of the Hours. What makes this living sacrifice ‘worthy and fit for his acceptance’ is that it is a participation in the only living sacrifice than can have that high worth, that is the sacrifice of Christ himself. There is only an upside to this. We get a free ride - we pray the liturgy, and in so doing open ourselves up to the reception of all the benefits of the supreme act of living made by someone else, without experiencing any of the pain. Christ bears all of that. It is an absurdly one-sided arrangement in our favour. It is such good news that it is scarcely believable, yet this is truly what we are offered through the Church. There is a standing offer already made, and our prayer is the act of acceptance.

Then, just in case we doubted that this living sacrifice is the prayer of the Church, we read the next morning in the Office of Readings a commentary by St Augustine on Psalm 140, 1-2. The Psalm passage he is commenting on reads as follows:

Then, just in case we doubted that this living sacrifice is the prayer of the Church, we read the next morning in the Office of Readings a commentary by St Augustine on Psalm 140, 1-2. The Psalm passage he is commenting on reads as follows:

‘I call upon you O Lord, listen to my prayer, Give ear to the voice of my supplication when I call to you.

Let my prayer be counted as incense before you, And the lifting up of my hands as an evening sacrifice.’

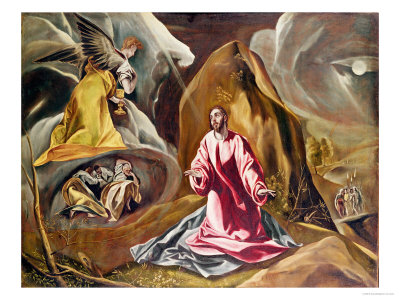

Within the commentary he explicitly makes the connection between the sacrifice and prayer of the faithful as part of the body of Christ, that is, the liturgy. He also explains how the pain and anguish that Christ felt in his passion is due to His bearing our sins and agony. The blood that streamed over his body when experiencing the agony in the garden was not due to anxiety for himself but, says Augustine: ‘Surely this bleeding of all his body is the death agony of all the martyrs of his Church’. We have just had the Feast of the martyrs Perpetua and Felicity. What is so striking the account of their deaths (again given in the Office of Readings) is how cheerfully and gracefully they bore the grevious mutilations that eventually killed them. I wonder at their purity and cooperation with grace and I wonder also at the fact that this pain is what Christ is choosing to experience on their behalf.

Augustine goes on to encourage us by saying that this is available to all of us: ‘All of us can make this prayer; this is not merely my prayer; the entire Christ prays in this way. But it is made rather in the name of the body…The evening sacrifice, the passion of the Lord, the cross of the Lord, the offering of a saving victim, the whole burnt offering acceptable to God; that evening sacrifice produced in his resurrection from the dead, a morning offering. When a prayer is sincerely uttered by a faithful heart, it rises as incense rises from a sacred altar. There is no scent more fragrant than that of the Lord. All who believe must possess this perfume.’

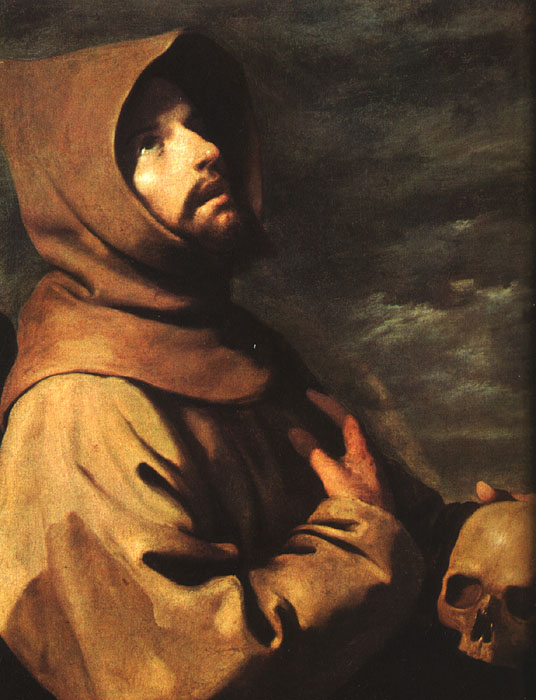

Paintings by, from top: El Greco, Rubens and Titian

New Liturgical Movement's Fr Thomas Kocik to Speak at Thomas More College this Friday

Fr Thomas Kocik, who writes for the New Liturgical Movement website on the Reform of the Reform (and has written a great book on this subject published by Ignatius Press, see here) will be speaking at Thomas More College of Liberal Arts in Merrimack, New Hampshire this Friday, October 14th, 7pm.

Entitled Singing His Song, Fr Kocik will be presenting an overview of the Liturgical Movement originating with Dom Guéranger and culminating with Sacrosanctum Concilium – its aims, principles, and leading proponents (without getting too involved in detail). He will discuss the good and bad fruits of the post-Vatican II liturgical reform, to provide the necessary background for the New Liturgical Movement now underway.

Fr Thomas Kocik, who writes for the New Liturgical Movement website on the Reform of the Reform (and has written a great book on this subject published by Ignatius Press, see here) will be speaking at Thomas More College of Liberal Arts in Merrimack, New Hampshire this Friday, October 14th, 7pm.

Entitled Singing His Song, Fr Kocik will be presenting an overview of the Liturgical Movement originating with Dom Guéranger and culminating with Sacrosanctum Concilium – its aims, principles, and leading proponents (without getting too involved in detail). He will discuss the good and bad fruits of the post-Vatican II liturgical reform, to provide the necessary background for the New Liturgical Movement now underway.

This will be the second visit that Fr Kocik has visited the college this year. In the spring he chaired our discussion on art and the liturgy, which was a lively and well attended event. His address at that event is here. His lecture, entitled Beauty and the Renewal of Catholic Culture spoke of the importance of liturgical renewal at the root of cultural renewal. A theme very close to my heart.

Fr Kocik is a priest in the diocese of Fall River, Mass.

Where Do Liturgy, Devotional Prayer and Meditation all Fit Together?

Shawn Tribe of the New Liturgical Movement writes about the relationship between Exposition and the Liturgy, (here).

Shawn Tribe of the New Liturgical Movement writes about the relationship between Exposition and the Liturgy, (here).  When I asked this question first, years ago, I was directed first to the Church's teaching on the liturgy in the Catechism and Sacrosanctum Concilium. In regard to Marian devotion, I later discovered an encyclical called Marialis Cultus, For the Right Ordering and Development of the Devotion to the Blessed Virgin Mary.

When I asked this question first, years ago, I was directed first to the Church's teaching on the liturgy in the Catechism and Sacrosanctum Concilium. In regard to Marian devotion, I later discovered an encyclical called Marialis Cultus, For the Right Ordering and Development of the Devotion to the Blessed Virgin Mary. Third, while the sacred liturgy (that is the Mass and the Liturgy of the Hours) is higher than any of them and contains a fuller expression of what the devotions point to, one should not interpret the raising of the liturgy to its proper position as an desire to diminish the importance of devotional prayers; and finally that many of the different aspects of prayer life including the meditative and the contemplative are accessible through liturgical practice.

Third, while the sacred liturgy (that is the Mass and the Liturgy of the Hours) is higher than any of them and contains a fuller expression of what the devotions point to, one should not interpret the raising of the liturgy to its proper position as an desire to diminish the importance of devotional prayers; and finally that many of the different aspects of prayer life including the meditative and the contemplative are accessible through liturgical practice.Beauty and the Renewal of Catholic Culture by New Liturgical Movement's Fr Thomas Kocik

The following is short opening address given at a symposium of working Catholic artists that recently took place at Thomas More College of Liberal Arts. It is a message of great hope for the future of Catholic culture.

The following is short opening address given at a symposium of working Catholic artists that recently took place at Thomas More College of Liberal Arts. It is a message of great hope for the future of Catholic culture.

Father Thomas Kocik, contributor to the New Liturgical Movement web site and former editor of Antiphon, the journal of the Society for Catholic Liturgy, chaired the discussion. He is a priest in the diocese of Fall River, Massachusetts. In his talk he tackled the subject right at the heart of any discussion about the re-establishment of culture. As he pointed out, the word "culture" derives from the Latin cultus, meaning what we cherish or worship. Christian culture is thus centered on Christ, the incarnate beauty of God. The "source and summit of the Christian life," (Lumen Gentium, #11) and therefore of Christian culture, is the Liturgy: Holy Mass, the sacraments, the different Hours of prayer that sanctify the entire day. In liturgical prayer, art and culture—indeed all human activity— finds true meaning; for at the center of the Liturgy is Christ, the source and summit of all human hope.

The full text of his talk follows here:

'The Second Vatican Council described the Sacred Liturgy as “the summit towards which the activity of the Church is directed” and “at the same time” as “the fount from which all her power flows” (SC 10).

All the power of the Church flows from the Sacred Liturgy: from the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass, the sacraments, and the unceasing round of liturgical prayer offered each day by the Church. If one does not nourish himself from this power source at least at Sunday Mass and through regular confession, the life of grace given him at Baptism will wither. He will risk spiritual death.

The Sacred Liturgy is the summit towards which all Christian activity — everything! — is directed. All human activity: political life, family life, social life, labor, leisure, the arts, acts of charity and compassion, even our struggles and suffering, find true meaning and fulfillment when they are offered to God and united with the sacrifice of Christ, the sacrifice of the Mass.

This, then, is why we are obliged (for our own good) to gather for liturgical prayer: to offer all aspects of our lives to God and to receive from Him all that we need to persevere in joyful service of God and our neighbor.

Now while Sunday Mass is a minimum, I would suggest that a Christian life, that any culture, that is not permeated by prayer is deficient. Another word for worship is “cult” and it is no coincidence that the word gives rise to the word “culture.” In a sense, our culture is an expression of what we worship – think of any so-called “cult figure.” And so, Christian culture is a culture in which Christ is adored, praised, loved, and worshiped.

Now while Sunday Mass is a minimum, I would suggest that a Christian life, that any culture, that is not permeated by prayer is deficient. Another word for worship is “cult” and it is no coincidence that the word gives rise to the word “culture.” In a sense, our culture is an expression of what we worship – think of any so-called “cult figure.” And so, Christian culture is a culture in which Christ is adored, praised, loved, and worshiped.

Although it may only be possible to participate in the Sacred Liturgy once a week, we can nevertheless keep our spirit of worship alive through prayer. Some do this by praying parts of the Liturgy of the Hours, and there could be no better prayer for daily use. Others do so with prayers such as the Angelus, which raises the mind and heart to God at morning, noon, and night. There are many other ways of so doing. The point is that it is done: that, like the farmer in Millet’s famous painting L’Angelus, amidst the duties and distractions that our different states in life present, we stop and we pray. When we do that, we will have done one more thing that helps bring about a restoration of Christian culture, in ourselves and in our society.

It is very easy for us to lament the loss of Christian culture and to be weighed down by the secularism all around us, and from which at times even the Church is not immune. But we must not forget who we are: we are Christians; we have been given the gift of God the Holy Spirit through our Baptism and Confirmation. We are a people constituted by faith, hope, and charity. Yes, our times present their challenges, but what times have not presented challenges? Christian culture was slowly built up over centuries from the foundation of the faith and witness of mere handfuls of individuals who personally encountered the Risen Christ and who gave their all in proclaiming Him as the Way, the Truth, and the Life. Perhaps we have lost much in recent decades; but our task is not to lament. It is to believe, to hope, to pray and to work with integrity for a renewal of all things in Christ. If the Apostles and early disciples could lay the foundations for Christian culture, so can we. For they, too, had to deal with an overwhelmingly hostile culture that did not know Christ. They too, in confessing a relationship with the person of Jesus Christ, were met with skepticism and, at times, violent hostility. And yet, with God’s help, they changed the course of history and influenced the cultures of countless peoples.

Let us therefore prefer nothing to the opus Dei, the work of God, the Sacred Liturgy. And let us ever be confident in what good following this precept can yield.'

Using the Principles of the Liturgy and Beauty in Retail

High Shelf Esteem! When James Woodward, owner of Woodward Menswear, decided to open a second high-end men’s clothes shop he wanted to model it upon the principles he had read about in the Way of Beauty. He had already started to put some of the principles into practice in his first shop, in Oxted in Surrey, England and had been encouraged the results. Because he was beginning with a blank page in this new venture, he saw the opening of his second shop in Banstead, also in Surrey, as an opportunity to use them more fully. I received a telephone call from him earlier this year asking for ideas about the layout and decoration of the new place.

He had already been trying some of these things out in the first shop, but hadn’t been able to implement them properly because a lot of the things were already set differently when he had thought about introducing them. Nevertheless the changes that he was able to make had made an impact he thought. The local bank manager had told him at one point, in the deepest part of the recession, that his was the only business on his books that showed any significant signs of growth. ‘I had been making money and I felt that this had contributed. The growth of the business is helping to fund the investment in this new shop. But it isn’t just the money,’ he told me. ‘The principles that I had been able to try seemed to show me a way of having the values of my Catholic faith penetrate much more deeply than before the everyday activities of business.’

High Shelf Esteem! When James Woodward, owner of Woodward Menswear, decided to open a second high-end men’s clothes shop he wanted to model it upon the principles he had read about in the Way of Beauty. He had already started to put some of the principles into practice in his first shop, in Oxted in Surrey, England and had been encouraged the results. Because he was beginning with a blank page in this new venture, he saw the opening of his second shop in Banstead, also in Surrey, as an opportunity to use them more fully. I received a telephone call from him earlier this year asking for ideas about the layout and decoration of the new place.

He had already been trying some of these things out in the first shop, but hadn’t been able to implement them properly because a lot of the things were already set differently when he had thought about introducing them. Nevertheless the changes that he was able to make had made an impact he thought. The local bank manager had told him at one point, in the deepest part of the recession, that his was the only business on his books that showed any significant signs of growth. ‘I had been making money and I felt that this had contributed. The growth of the business is helping to fund the investment in this new shop. But it isn’t just the money,’ he told me. ‘The principles that I had been able to try seemed to show me a way of having the values of my Catholic faith penetrate much more deeply than before the everyday activities of business.’

James is a Catholic convert of about 10 years. I had known him for several years because we both attended the London Oratory when I lived in London. We had had conversations about the Way of Beauty over the years, just as a result of staying in touch and his curiosity about what I was up to over here. At some point he started to ask me how he might introduce into what he was doing in his first shop. Even so, I was surprised to be asked recently to contribute so much to the new project.

James is a Catholic convert of about 10 years. I had known him for several years because we both attended the London Oratory when I lived in London. We had had conversations about the Way of Beauty over the years, just as a result of staying in touch and his curiosity about what I was up to over here. At some point he started to ask me how he might introduce into what he was doing in his first shop. Even so, I was surprised to be asked recently to contribute so much to the new project.

So what has he done? As a starting point I suggested that whatever he does he constantly ask himself the question, is this beautiful? And to be prepared to go against the trend of modern design if necessary. I did offer some specific points:

- The general layout is one that gives a general impression of symmetry and order. I suggested that he introduce some details of asymmetry. If it is too rigidly symmetrical it would be cold and sterile. He went directly against the advice of his retail designers here, who were recommending more sweeping and turning curves in the layout; and asymmetry ordered to the personal intuition of the designer. I suggest that the colour scheme should be based around natural earth colours if possible.

- The clothes are presented on shelves and I suggested that the spacing of the shelves should not be even, but should vary so that the largest spacing is at the bottom and smallest at the top, mimicking the proportions of storey size in traditional architecture.

- He has the natural beauty of plants in the shop too, either pot plants or cut flowers. Because there are people walking around the shop, this meant that he had to design into the layout spaces and shelves just for this purpose so that the arrangements could be placed without impeding the flow of people or the views of the clothes he was selling.

I told him to try to avoid pop or rock music and again, if you have music to opt for something that is beautiful. I am not completely against all pop music per se, but even good music that is designed for dancing at midnight is unlikely to promote calm and peace, which is what we were aiming for here. In the end James opted for no music at all. He was really sticking his neck out here. Almost all retailers install music systems and have background music constantly. The outfitters cite scientific studies that prove that when you play such music, people stay for a shorter period of time and buy more quickly. Also the staff initially wanted it too for their own entertainment. He is not certain he wants to maintain the silent vigil and is considering using classical music.

I told him to try to avoid pop or rock music and again, if you have music to opt for something that is beautiful. I am not completely against all pop music per se, but even good music that is designed for dancing at midnight is unlikely to promote calm and peace, which is what we were aiming for here. In the end James opted for no music at all. He was really sticking his neck out here. Almost all retailers install music systems and have background music constantly. The outfitters cite scientific studies that prove that when you play such music, people stay for a shorter period of time and buy more quickly. Also the staff initially wanted it too for their own entertainment. He is not certain he wants to maintain the silent vigil and is considering using classical music.- I felt it was important to have the face of Christ as a focus in the décor (a good principle for all main rooms in a building). In the end he bought a small icon of the mandylion and put it on the wall behind the till. This meant that every customer who went to the counter would see it. In his previous shop James put also a nativity scene in the window every Christmas and he intends to the same here. Aside from any thoughts about décor, he wanted to bear witness to his faith in an open, but quiet way. Again, the advice of the professionals on this one was the exact opposit! It would offend and put off non-Christians he was told. He has had no complaints from customers since he did this, and several complementary remarks. Small children were pulling their parents into the shop as a result of the nativity in the window.

- Finally, I had suggested that he pray the Liturgy of the Hours as part of his spiritual life and even if he couldn’t pray all the hours, try to mark each Office with a prayer of some sort. He might, I thought, consciously dedicate this prayer as a sacrifice for the well being of his employees and customers.

The photographs of the shop and are shown, so you can make your own mind up about the look. The shelves are solid oak veneer and the flooring is solid oak coupled with pure-wool carpeting. The paintwork is all natural-pigment traditional paint (produced to re-create eighteenth-century decorative schemes). What strikes me is that although traditional proportions and materials have been used, it has a clean-cut modern look. This is not trying to recreate and Italian villa or a Georgian town house. The modifications are subtle.

The photographs of the shop and are shown, so you can make your own mind up about the look. The shelves are solid oak veneer and the flooring is solid oak coupled with pure-wool carpeting. The paintwork is all natural-pigment traditional paint (produced to re-create eighteenth-century decorative schemes). What strikes me is that although traditional proportions and materials have been used, it has a clean-cut modern look. This is not trying to recreate and Italian villa or a Georgian town house. The modifications are subtle.

Clearly, using these high quality materials involves a greater outlay than the usual materials. He has now been going for about three months and when I spoke to him recently I was interested to know: did he feel the extra investment had been worthwhile?

‘The look of the place has had an impact. Several customers and other local retailers have complimented the shop actually using the word “beautiful”. For example I was at the local newsagents and the lady behind the till engaged me conversation. When she realized I was from the new Woodward Menswear she immediately told me that people had been saying to her how beautiful the shop was.

‘Many customers have told me how comfortable and inviting the shop is and one top-notch fellow fashion retailer said it was a really beautiful shop and “very calming”. What I find so interesting is that they can't really tell why it is. they respond to the overall look but they can't say why. I haven't made it look like a Victorian shop or anything, the look is similar in many respects to other shops, but the modifications are subtle. I think that unless it was pointed out to them, for example, they wouldn't know that the shelves are spaced differently to other places.’

And the bottom line?