Woody Allen is a filmmaker who I always wish was a Catholic. He observes human nature brilliantly and knows how to portray that in film; he has an erudite wit and he seems to be able to write this into the dialogue of his characters without it coming across as forced or affected; and he knows how to reflect a philosophical outlook in that dialogue in such a way that even if you don't agree with it, you find yourself enjoying the film and laughing at his jokes. The problem with many of his films is that while he very often knows how to portray the absurdity of modern philosophy, he does not always leave you with a good alternative. Sometimes, from the message portrayed in his films, you wonder if he is unsure himself what the answers are. When he does seem to offer answers, it has looked to me as if he is trying to justify whatever aspect of his tumultuous personal life most recently hit the news.

If only he was a Catholic, or alternatively we had Catholics who knew how to make films like Woody Allen, how much greater would those films be. Also, I would say in order to encourage any Catholic filmmakers out there, the films would be even more successful as a result because they would now represent more fully what is good and what is true. When any art form does this well, then it will have mass appeal for it will have greater beauty too.

Woody Allen is a filmmaker who I always wish was a Catholic. He observes human nature brilliantly and knows how to portray that in film; he has an erudite wit and he seems to be able to write this into the dialogue of his characters without it coming across as forced or affected; and he knows how to reflect a philosophical outlook in that dialogue in such a way that even if you don't agree with it, you find yourself enjoying the film and laughing at his jokes. The problem with many of his films is that while he very often knows how to portray the absurdity of modern philosophy, he does not always leave you with a good alternative. Sometimes, from the message portrayed in his films, you wonder if he is unsure himself what the answers are. When he does seem to offer answers, it has looked to me as if he is trying to justify whatever aspect of his tumultuous personal life most recently hit the news.

If only he was a Catholic, or alternatively we had Catholics who knew how to make films like Woody Allen, how much greater would those films be. Also, I would say in order to encourage any Catholic filmmakers out there, the films would be even more successful as a result because they would now represent more fully what is good and what is true. When any art form does this well, then it will have mass appeal for it will have greater beauty too.

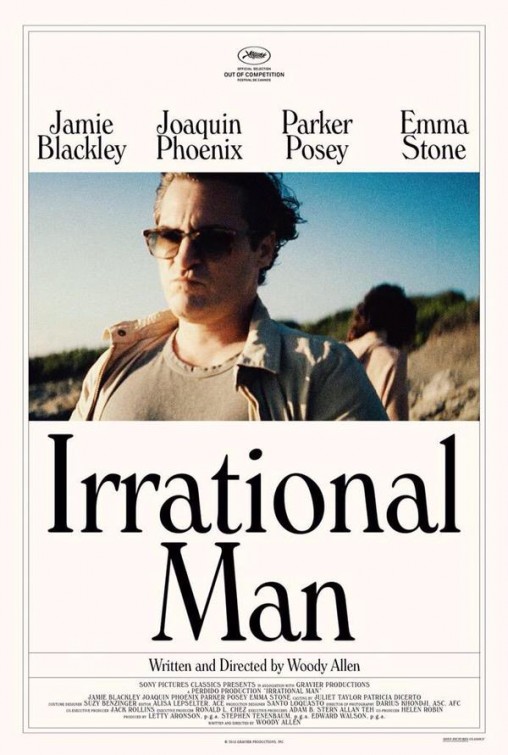

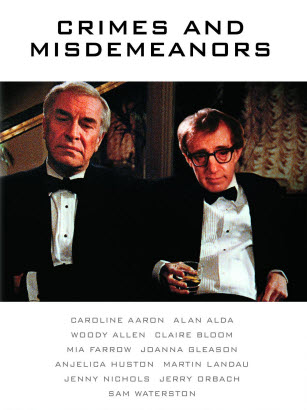

When I saw Woody Allen's latest film, the Irrational Man I wondered if (at the age of 79), he is changing. You will have to watch the film to see the plot, but in general terms, this one struck me as a new version of his 1989 film Crimes and Misdemeanors. Both have the well crafted dialogue and nicely observed human interactions in the context of the confused sexual politics of the liberal elite. And both have a murder in which the film examines the how the conscience of the murderer reacts and changes over time, placing this in the context of right and wrong.

There are two differences. First, the Irrational Man is not as funny - in this sense it is a little disappointing, but perhaps you need to the comic genius Allen himself or Alan Alda, who star in the earlier film, to deliver the lines. It seems that although there are a few chuckles as you go along, but I think that perhaps this wasn't Allen's intention with Irrational Man. Joaquin Phoenix, who plays a bitter and philandering (and murderous) philosophy professor in a Rhode Island college, plays it just right for me in a more serious role and doesn't make the mistake of trying to a replacement for Woody Allen in the way that he plays it.

The other is the nature of the philosophical message of the resolution of the film. In this respect I liked Irrational Man much more. In Crimes and Misdemeanors, the conscience of the murderer, played by Martin Landau, is at first tortured, but in time, the discomfort disappears and the film closes with him a scene of him laughing heartily and saying to friend that he has nothing on his mind that he regrets - in time he indicates, all guilt disappears. This was reinforced by the line from character played by Alan Alda, who said that in the end all comedy is just 'tragedy plus time' - ie the worse it is initially, the funnier it is in the end.

I remember thinking at the time that this was a dangerous message - it was saying that there is no objective right and wrong. No matter how bad something seems, its just the perception, and time if nothing else can change that. I am convert and part of what brought me to the faith was the realization that there was only one thing that would appease my conscience and that was the mercy of God. My experience was that no matter how I tried to tell myself I was good person, I did not believe it until I had confessed my wrong doing. If I had listened to the message of Crimes and Misdemeanors, I thought, I might have found it attractive initially, but I would still be hanging around just waiting until I felt better, feeling miserable and heading, very likely, for hell.  In the Irrational Man, on the other hand, the murderer is initially exhilarated by what he has done as he believes his own hype but as time progresses things get worse and his crime, so to speak, catches up with him. The voice of his conscience is the student with whom he is having an affair, played by Emma Stone, who is initially in thrall to his reputation and all that he does. Gradually, she realizes what he has done and reacts against his justifications and the philosophical theories that underpin them. Unlike the plot in Crimes and Misdemeanors, the effect on the murderer of his past action will not go away in time. It becomes clear that he must face a choice. Either acknowledge what he has done truthfully, or else continue the lie and try to erase the voice of his conscience. From the point of view of moral law, he makes the wrong choice and attempts to do the latter. The outcome of the protaganist here, again, unlike that of Crimes and Misdemeanors, is a just reward for his actions. So as I saw it, the film resolves itself in support of natural law, objective good and bad and a condemnation of the modern philosophy that the professor espoused in the classroom to his students.

In the Irrational Man, on the other hand, the murderer is initially exhilarated by what he has done as he believes his own hype but as time progresses things get worse and his crime, so to speak, catches up with him. The voice of his conscience is the student with whom he is having an affair, played by Emma Stone, who is initially in thrall to his reputation and all that he does. Gradually, she realizes what he has done and reacts against his justifications and the philosophical theories that underpin them. Unlike the plot in Crimes and Misdemeanors, the effect on the murderer of his past action will not go away in time. It becomes clear that he must face a choice. Either acknowledge what he has done truthfully, or else continue the lie and try to erase the voice of his conscience. From the point of view of moral law, he makes the wrong choice and attempts to do the latter. The outcome of the protaganist here, again, unlike that of Crimes and Misdemeanors, is a just reward for his actions. So as I saw it, the film resolves itself in support of natural law, objective good and bad and a condemnation of the modern philosophy that the professor espoused in the classroom to his students.

What is interesting is to me is to see how the mainstream film critics reviewed each film. They had just about the opposite reaction to me! They loved Crimes and Misdemeanors and at the time it was nominated for host of awards - best actor, best film, best director, best screenplay...the list goes on. But they hated the Irrational Man. I don't know if the differing reviews are a reflection of the differing quality of the films, or of the worldview of the critics. I suspect the latter!

— ♦—

My book the Way of Beauty is available from Angelico Press and Amazon.

—JAY W. RICHARDS, Editor of the Stream and Lecturer at the Business School fo the Catholic University of America said about it: “In The Way of Beauty, David Clayton offers us a mini-liberal arts education. The book is a counter-offensive against a culture that so often seems to have capitulated to a ‘will to ugliness.’ He shows us the power in beauty not just where we might expect it — in the visual arts and music — but in domains as diverse as math, theology, morality, physics, astronomy, cosmology, and liturgy. But more than that, his study of beauty makes clear the connection between liturgy, culture, and evangelization, and offers a way to reinvigorate our commitment to the Good, the True, and the Beautiful in the twenty-first century. I am grateful for this book and hope many will take its lessons to heart.”