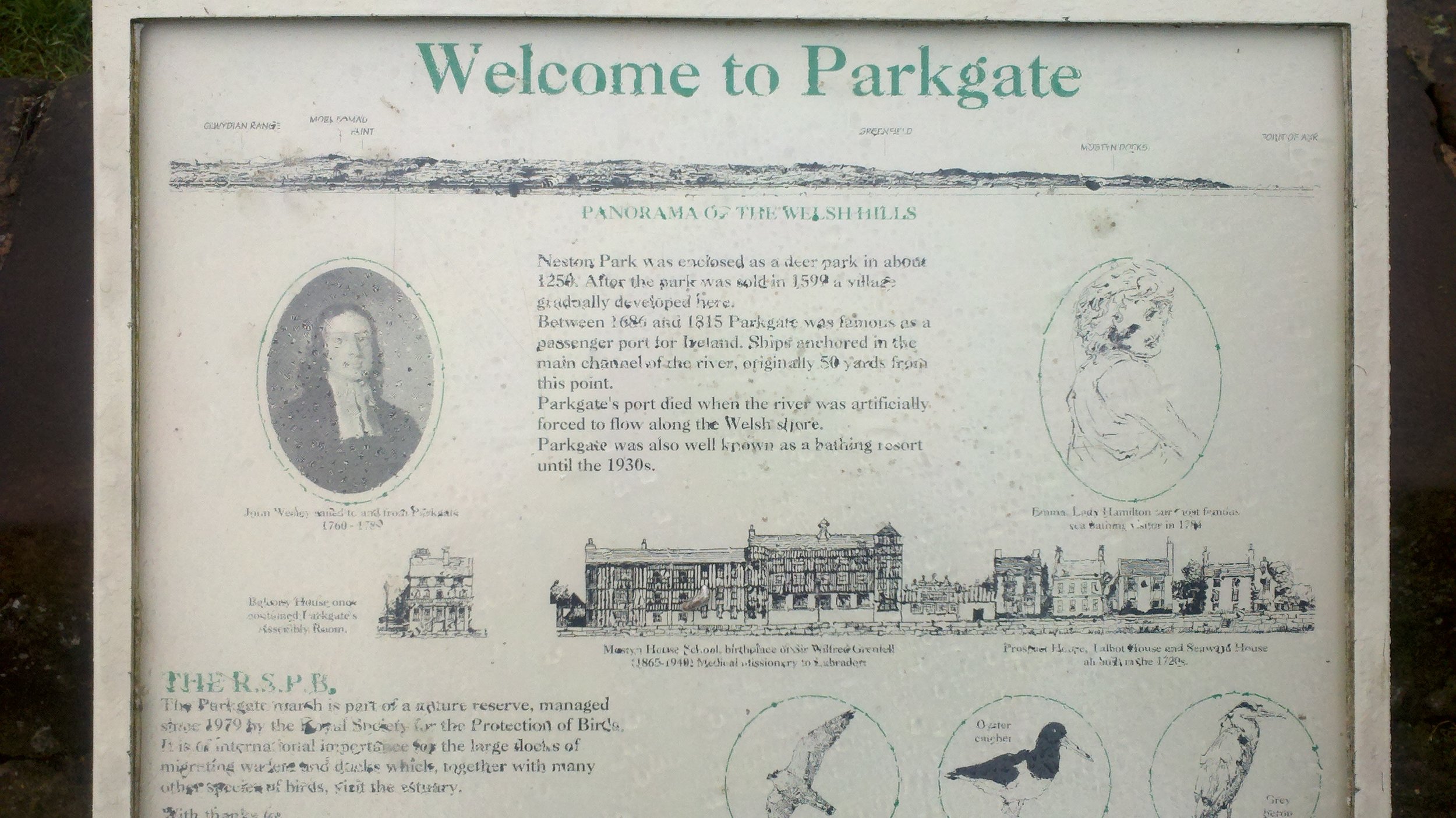

Is a bird reserve created by heavy industry a natural or an unnatural landscape? I grew up in a place called Neston, within a mile from my home there is the old seaside resort of Parkgate. It is on the estuary of the River Dee on the border between northwest England and north Wales. (Directly over the estuary on the Welsh side is the town of Holywell feartured last week.) I took these photographs during the visit earlier this year. I thought that readers will find the elegant Victorian seafront buildings interesting, but would be puzzled as to why they would build it on a marsh? This is an interesting story I think.

A hundred years ago this was a thriving seaside resort with a promenade with a wall and railings and stone steps, made out of the local red sandstone, going down to the beach. The estuary here was tidal and the waters came up to the sea wall at high tide and then retreat miles at low tide, revealing a huge expanse of sand. When my family came to live closeby in the 1960s it was still there and Parkgate was known in the wider area for a shop that sells homemade ice cream. There was even a tide-filled seawater swimming pool open to the public. Then gradually the beach began to be overgrown with a natural hybrid grass called spartina. One of the things that allowed this grass to grow was that a steel company, some miles further down the estuary, took the river waters for its industrial processes. In order to do this they change the course of the river and the tides didn't cover the sand as often - only at the very high spring tides, about twice a year.

Is a bird reserve created by heavy industry a natural or an unnatural landscape? I grew up in a place called Neston, within a mile from my home there is the old seaside resort of Parkgate. It is on the estuary of the River Dee on the border between northwest England and north Wales. (Directly over the estuary on the Welsh side is the town of Holywell feartured last week.) I took these photographs during the visit earlier this year. I thought that readers will find the elegant Victorian seafront buildings interesting, but would be puzzled as to why they would build it on a marsh? This is an interesting story I think.

A hundred years ago this was a thriving seaside resort with a promenade with a wall and railings and stone steps, made out of the local red sandstone, going down to the beach. The estuary here was tidal and the waters came up to the sea wall at high tide and then retreat miles at low tide, revealing a huge expanse of sand. When my family came to live closeby in the 1960s it was still there and Parkgate was known in the wider area for a shop that sells homemade ice cream. There was even a tide-filled seawater swimming pool open to the public. Then gradually the beach began to be overgrown with a natural hybrid grass called spartina. One of the things that allowed this grass to grow was that a steel company, some miles further down the estuary, took the river waters for its industrial processes. In order to do this they change the course of the river and the tides didn't cover the sand as often - only at the very high spring tides, about twice a year.

At first, people were unhappy with this. Here was heavy industry messing with the natural landscape. I can remember as a boy going to lecture about the threat of spartina grass and the speaker asking for volunteers to go and pull it out of the muddy sand and keep the estuary clear. It was a forlorn task and people soon gave up. Then something started to happen. The new wetland terrain that was created started to attract birds and birdwatchers flocked to the area to sea rare waders and shore birds such as Marsh Harriers and Hen Harriers. Now, 40 years later it is an award winning bird reserve that is listed as an area of outstanding natural beauty on the RSPB website.

At first, people were unhappy with this. Here was heavy industry messing with the natural landscape. I can remember as a boy going to lecture about the threat of spartina grass and the speaker asking for volunteers to go and pull it out of the muddy sand and keep the estuary clear. It was a forlorn task and people soon gave up. Then something started to happen. The new wetland terrain that was created started to attract birds and birdwatchers flocked to the area to sea rare waders and shore birds such as Marsh Harriers and Hen Harriers. Now, 40 years later it is an award winning bird reserve that is listed as an area of outstanding natural beauty on the RSPB website.

The steelworks, at Shotton in Wales, has changed hands several times since I was a boy and is now owned by Tata Steel, the Indian steel company. As far as I know its future and so that of the Parkgate Marsh Harriers are secure for the moment. But no company lasts forever and so one wonders, what will the environmentalists do if the steel company were to close? Would they let the river resume its natural course, so submerging the wetlands and destroying the manmade habitat of the birds? Or would they campaign for the preservation of the steel plant for the sake of the birds? For the Christian, there is no such dilemma. Man is as natural as as Marsh Harrier and making steel is a natural activity for man. So faced with a choice of keeping a manmade environment or one that is less affected by man, I would just choose the one I preferred. I this case, I'm not sure I could make up my mind, although as a boy I always wished that the swimming baths had stayed open. Either way, events will take their course; but should the steel company ever face closure (which I hope is a long way off) if we wanted to save it we would have to face the fact that man is as much part of the ecosystem as the black-tailed godwit. Would the plight of the Meadow Pipin push the Shotton steel plant into the category of being 'too big to fail', along with companies such as Barclay's Bank and Bank of America?... I wonder.

It was a rainy day when I visited, so you'll have to imagine the sunny seaside scene. In case you are interested, the ice cream shop survives to this day. I was only able to download one photograph of the old Parkgate, so I refer to a site, here, that has photographs of these sites in 1939, when it was a seaside resort.  Thank you to the Francis Frith collection for the photo above.

Thank you to the Francis Frith collection for the photo above.

Below we have what remains of the old swimming baths.

And just in case anyone makes the trip. The ice cream shop is on the right, below.