I thought I would do a short series (I intend three at this stage) of articles focussing on paintings by the gothic artists, looking at two of my favourites Fra Angelico and Duccio. Fra Angelico, the 15th century Florentine artist is normally considered late gothic in style. Duccio, from Siena, worked earlier, in the late 13th and early 14th centuries. Duccio's work represents the more iconographic based style and Fra Angelic the more naturalistic. Looking at these two exemplars of early and late gothic art gives us a good sense of what characterises this tradition.

This is not just for the purpose of an art history discussion. I think that there is much to benefit from artists today who are trying to spark the ‘new epiphany of beauty’ by looking at the gothic tradition. First, it is one of the three authentic Catholic liturgical traditions cited by Pope Benedict XVI in The Spirit of the Liturgy. Also, I often find in conversation that his work appeals to people who have a similar understanding of the Faith, the liturgy and Catholic culture as I do. It seems that for many, Fra Angelico in particular has the balance of naturalism and idealism that nourishes the prayer of modern man. John Paul II gave him a special mention in his Letter to Artists. I think therefore that perhaps this could be a good starting point for artists to study and from which a distinctive art of Vatican II could develop in the future (just as the baroque, which developed from the base of the stylistic developments of the High Renaissance, might be considered the art of the counter-Reformation and of the Council of Trent). Only time will tell if I am right in this regard, of course.

I thought I would do a short series (I intend three at this stage) of articles focussing on paintings by the gothic artists, looking at two of my favourites Fra Angelico and Duccio. Fra Angelico, the 15th century Florentine artist is normally considered late gothic in style. Duccio, from Siena, worked earlier, in the late 13th and early 14th centuries. Duccio's work represents the more iconographic based style and Fra Angelic the more naturalistic. Looking at these two exemplars of early and late gothic art gives us a good sense of what characterises this tradition.

This is not just for the purpose of an art history discussion. I think that there is much to benefit from artists today who are trying to spark the ‘new epiphany of beauty’ by looking at the gothic tradition. First, it is one of the three authentic Catholic liturgical traditions cited by Pope Benedict XVI in The Spirit of the Liturgy. Also, I often find in conversation that his work appeals to people who have a similar understanding of the Faith, the liturgy and Catholic culture as I do. It seems that for many, Fra Angelico in particular has the balance of naturalism and idealism that nourishes the prayer of modern man. John Paul II gave him a special mention in his Letter to Artists. I think therefore that perhaps this could be a good starting point for artists to study and from which a distinctive art of Vatican II could develop in the future (just as the baroque, which developed from the base of the stylistic developments of the High Renaissance, might be considered the art of the counter-Reformation and of the Council of Trent). Only time will tell if I am right in this regard, of course.

The gothic style arose from a different understanding of man's perception of the natural world through his senses. The ideas that drove it developed from about 1000AD onwards with the rediscovery of the philosophy of Aritotle and the subsequent incorporation of his ideas into Christian thinking by figures such as St Thomas. The love of nature of Franciscan spirituality was also influential in popularizing the ideas. I have written more about this here.

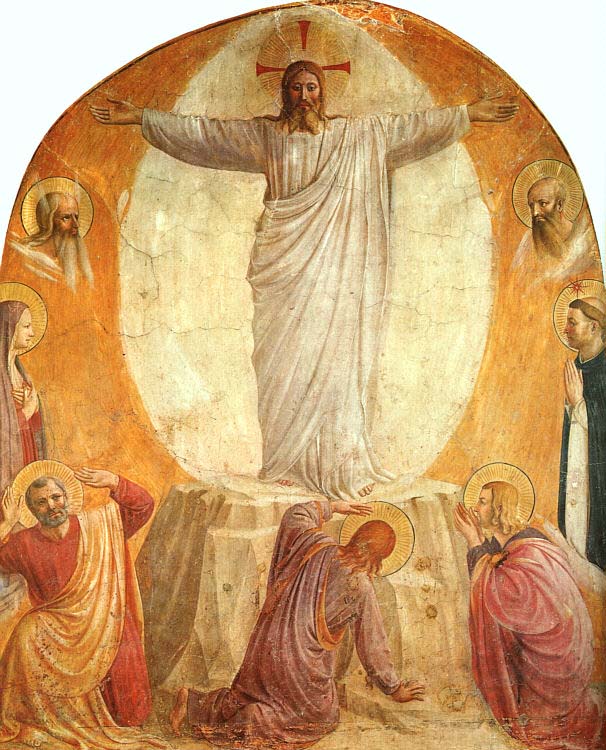

As I wrote in a commentary on his Annunciation, Fra Angelico working late in the period is very interesting to study for his selective use of the features of the well observed naturalism such as perspective, shadow and figures in profile; and his retention at other times of those features of iconographic art.

If we look his Resurrection a fresco from one of the cells in the monastery of San Marco in Florence, we see Christ rising in an almond shaped mandorla, the traditional symbol of His glory, carrying the red and white Resurrection penant. The background is shadowy and dark and we see the tomb drawn with naturalistic perspective. The angel is in profile, which would never be seen in an iconographic painting, though shining with uncreated light which one would expect in iconographic art.

There is one stylistic feature that Fra Angelico uses that interests me greatly. This is his habit of putting the face of Christ in shadow. On first sight this is strange, since he shows the rest of the person of Christ shining with light and the face of the angel, a great, but nevertheless lesser being is totally in light. When I first noticed this I wondered why? A Dominican friar in England told me his interpretation of this: Fra Angelico is showing a light that is brighter still. In fact it is so bright that it blinds us - it is too much for us, fallen human beings who are observing Him, to bear. I find this explanation convincing, especially because we see in in other paintings by Fra Angelico, for example the Transfiguration and the Sermon on the Mount have the same feature.