To repeat our opening words, we act as we see. The first step is therefore education, not education merely to swell our head knowledge, but to check, and if necessary, recalibrate, our vision of the world and of our worship.

The Icon and the Feast of the Exhaltation of the Holy Cross

Sacred Art That Survived the Oppression of the Church in Britain and Ireland Up for Auction

Byzantine Ressourcement? Liturgical Reform in the Orthodox Churches, as a Model for the Roman Rite

Churches Should Look Like Airports, But Not Like This

Contemporary Icons from Poland

How Does An Artist Deal With Rejection?

Rejection and failure are facts of our existence. When an artist's work is rejected or negatively critiqued, he or she is often told "don't take it personally, they are not rejecting you, just your work." This is a reflection of post-enlightenment thinking that considers art an end unto itself. It considers art in a vacuum, unrelated to the context in which it was created or the purpose it serves because to our modern way of thinking, those considerations are irrelevant.

Do We Need A New Christian Symbolism in Art - Aren't Pelicans and Peacocks Redundant?

Should we resurrect the old Christian symbolism? Or are pelicans and peacocks just nonesense, like cabbages and kings.

Should we resurrect the old Christian symbolism? Or are pelicans and peacocks just nonesense, like cabbages and kings.

Is there a danger that trying to reestablish traditional Christian symbols in art would sow confusion rather that clarity? Lots of talks and articles about traditional Christian art I see discuss the symbolism of the iconographic content; for example, the meaning of the acacia bush (the immortality of the soul) or the peacock (again, immortality). This is useful if we have a printed (or perhaps for a few of you an original) Old Master in church or a prayer corner as it will enhance our prayer life when contemplating the image. But is this something that we ought to be aiming to reinstate the same symbolism in what we produce today? Should we seek to educate artists to include this symbolic language in their art?  If symbols are meant to communicate and clarify, they should be readily understood by those who see them. This might have been the case when they were introduced – very likely they reflected aspects of the culture at the time – and afterwards when the tradition was still living and so knowledge of this was handed on. But for most it isn’t true now. How many would recognize the characteristics of an acacia bush, never mind what it symbolizes? If you ask someone today who has not been educated in traditional Christian symbolism in art what the peacock means, my guess is that they are more likely to suggest pride, referring to the expression, ‘as proud as peacock’. So the use of the peacock would not clarify, in fact it would do worse than mystify, it might actually mislead. (The reason for the use of the peacock as a symbol of immortality, as I understand it, is the ancient belief that its flesh was incorruptible). So to reestablish this sign language would be a huge task. We would not only have to educate the artists, but also educate everyone for whom the art was intended to read the symbolism. If this is the case, why bother at all, it doesn’t seem to helping very much, and in the end it will always exclude those who are not part of the cognoscenti . This is exactly the opposite of what is desired: for the greater number, it would not draw them into contemplation of the Truth, but push them out. I think that the answer is that some symbols are worth persevering with, and some should be abandoned. First, it is part of our nature to ‘read’ invisible truths through what is visible. This does not only apply to painting. The whole of Creation is made by God as an outward ‘sign’ that points to something beyond itself to Him, the Creator. Blessed John Henry Newman put it in his sermon Nature and Supernature as follows: "The visible world is the instrument, yet the veil, of the world invisible – the veil, yet still partially the symbol and index; so that all that exists or happens visibly, conceals and yet suggests, and above all subserves, a system of persons, facts, and events beyond itself.” It is important to both to make use of this faculty that exists in us for just this purpose; and to develop it, increasing our instincts for reading the book of nature and in turn, our faith.

If symbols are meant to communicate and clarify, they should be readily understood by those who see them. This might have been the case when they were introduced – very likely they reflected aspects of the culture at the time – and afterwards when the tradition was still living and so knowledge of this was handed on. But for most it isn’t true now. How many would recognize the characteristics of an acacia bush, never mind what it symbolizes? If you ask someone today who has not been educated in traditional Christian symbolism in art what the peacock means, my guess is that they are more likely to suggest pride, referring to the expression, ‘as proud as peacock’. So the use of the peacock would not clarify, in fact it would do worse than mystify, it might actually mislead. (The reason for the use of the peacock as a symbol of immortality, as I understand it, is the ancient belief that its flesh was incorruptible). So to reestablish this sign language would be a huge task. We would not only have to educate the artists, but also educate everyone for whom the art was intended to read the symbolism. If this is the case, why bother at all, it doesn’t seem to helping very much, and in the end it will always exclude those who are not part of the cognoscenti . This is exactly the opposite of what is desired: for the greater number, it would not draw them into contemplation of the Truth, but push them out. I think that the answer is that some symbols are worth persevering with, and some should be abandoned. First, it is part of our nature to ‘read’ invisible truths through what is visible. This does not only apply to painting. The whole of Creation is made by God as an outward ‘sign’ that points to something beyond itself to Him, the Creator. Blessed John Henry Newman put it in his sermon Nature and Supernature as follows: "The visible world is the instrument, yet the veil, of the world invisible – the veil, yet still partially the symbol and index; so that all that exists or happens visibly, conceals and yet suggests, and above all subserves, a system of persons, facts, and events beyond itself.” It is important to both to make use of this faculty that exists in us for just this purpose; and to develop it, increasing our instincts for reading the book of nature and in turn, our faith.  However, coming back to the context of art again, some discernment should be used, I suggest. I would not be in favour of creating an arbitrarily self-consistent symbolism. The symbol must be rooted in truth. The symbolism in the iconographic tradition is very good at following this principle. This is best illustrated by considering the example of the halo. This is very well known as the symbol of sanctity in sacred art. There are very good reasons for this. The golden disc is a stylized representation of a glow of uncreated, divine light, shining out of the person. Even if this were not already a widely known symbol, it would be worth educating people about the meaning of it, because in doing so something more is revealed. When however, the representation of a halo develops into a disc floating above the head of the saint, as in Cosme Tura’s St Jerome, or even a hoop, as in Annibale Caracci’s Dead Christ Mourned, (both shown) then it seems to me that the symbol has become detached from its root. Neither could be seen as a representation of uncreated light. These latter two forms, therefore, should be discouraged.

However, coming back to the context of art again, some discernment should be used, I suggest. I would not be in favour of creating an arbitrarily self-consistent symbolism. The symbol must be rooted in truth. The symbolism in the iconographic tradition is very good at following this principle. This is best illustrated by considering the example of the halo. This is very well known as the symbol of sanctity in sacred art. There are very good reasons for this. The golden disc is a stylized representation of a glow of uncreated, divine light, shining out of the person. Even if this were not already a widely known symbol, it would be worth educating people about the meaning of it, because in doing so something more is revealed. When however, the representation of a halo develops into a disc floating above the head of the saint, as in Cosme Tura’s St Jerome, or even a hoop, as in Annibale Caracci’s Dead Christ Mourned, (both shown) then it seems to me that the symbol has become detached from its root. Neither could be seen as a representation of uncreated light. These latter two forms, therefore, should be discouraged.

Similarly, those symbols that are rooted in the gospels or in the actual lives of the saints should be encouraged and the effort should be made, I think, to preserve or, if necessary, reestablish them. The tongs and coal of the prophet Isaias relate to the biblical accounts of his life. The inclusion of these, will generate a healthy curiosity in those who don’t know it, and so might direct them to investigate scripture. The picture shown, is one of my own icons.

In contrast consider the peacock and the pelican. The peacock, as already mentioned, does not, we now know, have incorruptible flesh. The pelican is a symbol of the Eucharist based upon the erroneous belief in former times that pelicans feed their young with their own flesh. My first though is that these symbols should not be used should not be used, because the reason for their symbolism in invalid, given that we no longer believe it to be true. However, I will admit that I am torn by the fact that both of these are beautiful and striking images, even if based in myth. Also, it might be argued, and this is particularly true for the pelican, that to use it is not resurrecting an obscure medieval symbol. It is an ancient symbol certainly - and St Thomas Aquinas's hymn to the Eucharist, Adore te devote called Christ the 'pelican of mercy'. But it lasted well beyond that. It was very widely understood even 50 years ago. Awareness of it is still common nowadays amongst those who are interested in liturgy and sacred art. Perhaps an argument could be made that even when the reason for the use of symbol is based in myth, if that is known and understood, and when that symbol recognition is still widespread enough to be considered part of the tradition, it should be retained. We should also remember that modern science is not infallible, and we moderns could be those who are mistaken about the pelican! My Googling research (admittedly even less reliable than modern science) revealed that the coat of arms of Cardinal George Pell has the image of the pelican. If this is so, I imagine he would have something to say about the issue also!

The 19th Century Beuronese School, An Inspiration for Artists Today?

Stylistically, Beuronese school is an interesting cul-de-sac that sits outside the mainstream of the Christian tradition. It is named after the town of Beuron in Germany which is the location of the Benedictine community in which the school originated in the mid-19th century.

The most well known artists who painted in this style in Europe are Desiderius Lenz (d 1928) and Gabriel Wuger (d 1892). In the United States, the walls and the ceiling of the abbey church of the Benedictines at Conception Abbey in Missouri, are decorated primarily with authentic examples of the Beuronese style. The abbey website tells us that the work was done between 1893 and 1897, by several monks of Conception, most notably Lukas Etlin (d. 1927), Hildebrand Roseler (d. 1923), and Ildephonse Kuhn (d. 1921), the latter two of whom had studied art at Beuron.

The original Beuronese artists were reacting against what was the dominant form of sacred art being painted for the churches of the Roman Rite at the time. This dominant style was an overly naturalistic and sentimental form of academic art, the product of the French academies and ateliers. The most well known artist of this decadent form is probably the Frenchman Bougeureaux. (For an in-depth discussion of this over naturalism in academic art read Is Some Sacred Art Too Naturalistic?)

Authentic Christian art has a style that is always a carefully worked out balance of naturalism (sometimes referred to as ‘realism’) and idealism. The naturalism in art tells us visually what is being painted – put simply if you want to paint a man it must look like a man, with a human body and limbs and so on. The idealistic element of the style is a controlled deviation from strict adherence to natural appearances by which the artist reveals invisible truths. The invisible truths that the artist might reveal, though style, are that man has a soul and a spirit that is intellect and will, for example.

It is this deviation from strict ‘photographic’ naturalism that characterizes the style of art (although in reality even a camera lens distorts appearances in a way that causes a photograph to be subtly different from what the eye actually sees). All paintings in any particular tradition will have in common particular methods of controlled abstraction that are carefully worked out to reveal the Christian understanding of what it portrayed. It is through perception of these that we are able to recognise the style. For example, we recognise the iconographic style because of, for example, an enlargement of the eyes, the dimunition of the mouth, and the elongation of the nose, in a particular way. These elements of iconographic style were developed to suggest to the observer a particular characteristics in the person portrayed that are appropriate for a saint.

It is as easy to distort appearances to hide truth and to create the equivalent of a visual lie through style, incidentally. Many advertising hoardings have photographs that are composed and then usually ‘airbrushed’ – that is, deliberately distorted - so as to to exaggerate in an imbalanced way the aspect of sexual attraction (and so, it is believed, sell products). This tells us that it is not enough to stylize, the Christian artist has a great responsbility and must understand deeply how his stylization is going to reveal truth, rather than hide it. If he gets it wrong he can lead souls astray. It's not just what he paints, it's how he paints it. (I hesitated to portray the image, below right, which I see as an example of art that has an anti-ideal. It is about at the limit of what I feel I can show and even then I felt I had to make is small.. Bear in mind it is intended for a children's comic.)

Aware of the deficiencies of the sacred (and mundane art) of their own time, Beuronese art sought to introduce an idealization into their style by seeking inspiration from ancient Egyptian art and from the Greek ideal. Visually it is easy to see the influence of the Egyptian papyri; but in addition the Beuronese artists used a canon of proportion that was said to be derived from that of the ancient Greeks (although this is speculative on their part, given that the canon of Polyclitus is lost). The link between ancient Greek art and Egyptian art is not an unnatural one. Plato praised the Egyptian style and it has been speculated that Greek art from the classical period (around 500 BC) was influenced by Egyptian art. The Beuronese artists themselves were trained in the methods of the19th century atelier and the result is a curious mixture, 19th century naturalism stiffened up, so to speak, by an injection of what they believed to be Egyptian art and Greek geometry.

What of the painting of Beuronese art today? In his encyclical about the sacred liturgy, Mediator Dei, Pius XII made it clear (in paragraph 195) that we should always be open to different styles of art for the liturgy provided any style under consideration: has the right balance of naturalism and idealism (he uses the words ‘realism’ and ‘symbolism’ to refer to these qualities); and that what drives its use is the need of the Christian community and not the whim of the artist or patron. In my experience, the Bueronese style does connect with people today in the right way so that it is appropriate for the liturgy. It has the sufficient naturalism so that one can recognise easily what they are looking at; and sufficient idealism that it does suggest another world beyond this one. Furthermore, contemporary culture does seem to provide naturally enough cultural reference points to allow modern people, even those without a classical education, to relate to this style. Art deco architecture, for example, is also derived from Egyptian styles. Strangely, many might find the Beuronese style with its Egyptian roots more accessible than a traditional icon in the classic Russian style of Andrei Rublev.

I have read an account of the geometric proportions used in the human form in translation of the book written by their main theorist Fr Desiderius Lenz, On the Aesthetic of Beuron. It was so complex that my reaction was that it would be very difficult for any painter to use the canon succesfully in any but very formal poses. As soon as an artist seeks to twist and turn a pose in the image, then the necessary foreshortening requires the painter to use an intuitive sense as to how the more distant parts relate to the nearer. Usually this means that in these cases he is less able to adhere to the cannon of proportion so well. This might account for that fact that when the figures are in less stiff and formal, Bueronese art seems to work less well, in my opinion. To my eye, the more relaxed poses produce art that looks like illustrations from the bible I was given when I was a child. Good in that context, perhaps, but too naturalistic for the liturgy I would say.

The approach of original Beuronese school is idiosyncratic – I do not know of any other Christian style of liturgical art that looked to ancient Egypt for inspiriation. Nevertheless the end result, when done well, does strike me as having something of the sacred to it and being worthy of attention. Perhaps their efforts to control the modern temptation to individual expression have contributed to this too. The school stressed, for example, the value of imitation of prototypes above the production of works originating in any one artist, furthermore the artists collaborated on works and did not sign it once finished.

Note, the icon detail is from a contemporary icon at St John the Baptist, Euless, TX, painted by Vladimir Grygorenk

Below I show some examples of Beuronese art that I think are less successful than the examples above. The first is less formal and ends up looking like a good illustration for a children's bible, but not so good for the liturgy, I suggest.

The next is highly skilled, but a little to close to 19th century naturalism for my liking.

Making People Smile in the Cry Room!

This has been inspired by photographs sent to me by friends who spent Easter at St. William's parish in Greenville, Texas. They were struck by the effort that the priest, Fr Paul Weinberger had made to make the cry room holy.

As Sherri wrote to me: 'The cry room is pretty small, but Fr. Paul has managed to fit in a lot for the little ones to examine, and it really adds a sense of holiness to the room.

'How simple but clever to put everything behind locked glass storm doors, so it is both accessible to the kids for viewing and yet safe from little hands. It's like a tiny museum! Besides the items behind glass, there are wooden statues of saints and Angels on the top of each cabinet, keeping a watchful eye on the kids.'

George and Katy Rose are the boy and girl in photos. It takes something pretty powerful to keep young George quiet, I know, so Fr Paul must be getting something right. So, if anyone has anything interesting from their cry room, send the photos along!

Should We Paint God the Father?

One of the most famous pieces of sacred art that exists is Michelangelo’s fresco, in the Sistine Chapel, of God giving the spark of life to Adam. Despite its popularity and familiarity, I had often wondered about the validity of representing God the Father.

My own instincts run against the idea of portraying God the Father in a painting at all, even when I was a child (I always thought that the white-whiskered God looked more like God the Grandfather, than God the Father). Later on in life, this was reinforced by the fact that my icon painting training led me to believe that it was wrong. I was pretty sure, but not certain, that it was not part of the tradition. Certainly, I have never painted an icon of God the Father. Furthermore, the theology of Theodore the Studite in regard to sacred imagery, which is accepted by both Eastern and Western Churches, bases the argument for the creation of any figurative art upon the fact that we can portray the person of Christ as man. The person of God the Father is a spiritual being and most certainly not man. This would seem to suggest that we should not portray the Father as man either.

One of the most famous pieces of sacred art that exists is Michelangelo’s fresco, in the Sistine Chapel, of God giving the spark of life to Adam. Despite its popularity and familiarity, I had often wondered about the validity of representing God the Father.

My own instincts run against the idea of portraying God the Father in a painting at all, even when I was a child (I always thought that the white-whiskered God looked more like God the Grandfather, than God the Father). Later on in life, this was reinforced by the fact that my icon painting training led me to believe that it was wrong. I was pretty sure, but not certain, that it was not part of the tradition. Certainly, I have never painted an icon of God the Father. Furthermore, the theology of Theodore the Studite in regard to sacred imagery, which is accepted by both Eastern and Western Churches, bases the argument for the creation of any figurative art upon the fact that we can portray the person of Christ as man. The person of God the Father is a spiritual being and most certainly not man. This would seem to suggest that we should not portray the Father as man either.

I quietly suspected that the white-bearded God of Michelangelo or William Blake or even my favourite baroque artist Velazquez were all in error, his Crowning of the Virgin by the Trinity is to the right. I wasn't too worried about Blake, an eccentric non-Catholic, but Michelangelo and Velazquez?

I quietly suspected that the white-bearded God of Michelangelo or William Blake or even my favourite baroque artist Velazquez were all in error, his Crowning of the Virgin by the Trinity is to the right. I wasn't too worried about Blake, an eccentric non-Catholic, but Michelangelo and Velazquez?

I was approached recently to do a commission that involves the portrayal of the Father. Rather than reject it out of hand, I thought I had better find out where the Church stands on this.

Here’s what my first investigations have revealed. For the first thousand years or so of Christianity, East and West, there was little portrayal of the Father figuratively. Then images started to appear in both the Eastern and Western traditions, though it was more common in the West.

There are two simple arguments that I have found for the representation of the Father: the first is that Christ said in John 14:9 that whoever has seen me has seen the Father. This would seem to open up to a representation of the Father as the Son. So, one could say, seeing an image of the Sacred Heart of Jesus is also seeing one of the Sacred Heart of the Father, with the heart of the Father understood as a symbol of His love.

![]() The second is that the white-bearded figure, which we are all familiar with is the Ancient of Days in the book of Daniel (7:9, 13, 22). This is the source of so many familiar portrayals of the Father. In the East there is a tradition known as the New Testament Trinity. This title would distinguish it from the Hospitality of Abraham (in which three angelic strangers represent the three persons of the Trinity). Right is a Greek Orthodox New Testament Trinity from the ceiling of the entrance Vatopedion Monastery at Agion Oros (Mount Athos), Greece. The Catholic Church, allows for the interpretation of the Ancient of Days as the Father, which justifies the portrayal of the Father. (I have been told that Pope Benedict XIV [fourteenth, not sixteenth!] in 1745 pronounced this, though beyond a Wikipedia reference I have not been able to validate this). It also allows for the interpretation of the Ancient of Days as Christ. The Russian Orthodox Church, since the synod of Moscow in 1667 has forbidden the portrayal of God the Father as a man. Consistent with this it interprets the Ancient of Days strictly as the Son. It is this decision of the pronouncement by the Russian church that gave me the idea, wrongly, that it had never been part of the Eastern tradition and that the whole present Eastern Church forbids it.

The second is that the white-bearded figure, which we are all familiar with is the Ancient of Days in the book of Daniel (7:9, 13, 22). This is the source of so many familiar portrayals of the Father. In the East there is a tradition known as the New Testament Trinity. This title would distinguish it from the Hospitality of Abraham (in which three angelic strangers represent the three persons of the Trinity). Right is a Greek Orthodox New Testament Trinity from the ceiling of the entrance Vatopedion Monastery at Agion Oros (Mount Athos), Greece. The Catholic Church, allows for the interpretation of the Ancient of Days as the Father, which justifies the portrayal of the Father. (I have been told that Pope Benedict XIV [fourteenth, not sixteenth!] in 1745 pronounced this, though beyond a Wikipedia reference I have not been able to validate this). It also allows for the interpretation of the Ancient of Days as Christ. The Russian Orthodox Church, since the synod of Moscow in 1667 has forbidden the portrayal of God the Father as a man. Consistent with this it interprets the Ancient of Days strictly as the Son. It is this decision of the pronouncement by the Russian church that gave me the idea, wrongly, that it had never been part of the Eastern tradition and that the whole present Eastern Church forbids it.

There is a Western tradition of portrayal of the trinity in a type known as the Throne of Mercy, in which the Father sits on his throne and presents his crucified son to the viewer while a dove rests on the cross or hovers just above it. It was this that was explicitly mentioned by Benedict XIV. A 16th century German version is shown left. This tradition goes right back the Medieval times in the Western Church and we have this continued even into the 20th century with Eric Gill in England doing woodcut of this image in a modern gothic style.

There is a Western tradition of portrayal of the trinity in a type known as the Throne of Mercy, in which the Father sits on his throne and presents his crucified son to the viewer while a dove rests on the cross or hovers just above it. It was this that was explicitly mentioned by Benedict XIV. A 16th century German version is shown left. This tradition goes right back the Medieval times in the Western Church and we have this continued even into the 20th century with Eric Gill in England doing woodcut of this image in a modern gothic style.

So where do I stand on this now? Clearly the portrayal of the Father as a grey-haired man is permitted. I would feel on safest ground following the traditional presentations, such as the Mercy Throne image. Outside that, I would be consider images, but would be cautious, unwilling to promote, as Caroline Farey of the School of the Annunciation put it to me, ‘any trend of anthropomorphizing God the Father in case the transcendence of God is further compromised in people's imaginations.’

It is worth pointing out also, that when God is portrayed as a single person in the form of the Ancient of Days, we cannot be sure that it is the Father who is portrayed. The artist might, quite justifiably, have the intention of representing the Son. I have not, for example, been able to find an authoritative text that tells us precisely which person of the Trinity either Michelangelo or Blake intended us to be looking at (I would welcome comments from readers on this point).

Below: an early gothic Mercy Throne; a 20th century version by the Englishman, Eric Gill; an early gothic pieta in which God the Father supports the son; a baroque Mercy Throne by Ribera, 17th century; and William Blake's Ancient of Days.

Just Because I Like It, It Doesn't Mean It's Good

If I can't trust my taste in food, can I trust my taste in art? I like chocolate cake. I don't know for certain, but I am guessing that there aren't many nutritionist out there who would argue that chocolate cake is good food. So here's the point. If the food I like isn't necessarily good food, might it be true also for the art I like?

If I can't trust my taste in food, can I trust my taste in art? I like chocolate cake. I don't know for certain, but I am guessing that there aren't many nutritionist out there who would argue that chocolate cake is good food. So here's the point. If the food I like isn't necessarily good food, might it be true also for the art I like?

Good art, I would maintain, communicates and reflects truth; and it is beautiful. There should never be any conflict between the good, the true and beautiful for they are all aspects of being and exist in the object being viewed, for example a painting. However sometimes it might appear as though there is a conflict. We might think something is false, yet find it beautiful for example.

Or that something is ugly but good. I have heard some people say that they like Picasso’s Guernica, see below, because its ugliness speaks of suffering. I would say contrary to this that if it is ugly, and it looks it to me, it must be bad. (I might go on and explain that this is contrary to truth because Christian art reveals suffering, but always with hope rooted in Christ, the Light of the World who overcomes the darkness. Such a painting, if successful will always be beautiful. what Geurnica lacks is Christian hope. ) In regard to the general principle, who is right? How can we account for these apparent contradictions between the good and the beautiful?

Many today would respond by asserting the subjectivity of the viewer. That is, they would say that my premise is wrong and the qualities good, true and beautiful are just a matter of personal opinion; and they are not necessarily tied to each other in the way I described. If they are right then there is nothing disordered about liking ugliness; or hating beauty; or thinking that something is both ugly and good at the same time.

I do not accept this. The answer for me lies in accepting that we have varying abilities to recognize goodness, truth and beauty. This gap between reality and our perception of it has its roots in our impurity. Since the Fall, we see these qualities only ‘through a glass darkly’ so to speak and our judgement, to varying degrees, can be disordered. This is where food comes into the discussion.

Now, more than chocolate cake, I love fluorescent-orange cheesey corn puffs. In England are they are called Cheezy Wotsits (pictured right...and don’t they look delicious!). I have an insatiable appetite for these wonderful dusted pieces of crunchy manna. The dust they are coated with is 'cheese-flavoured' - there's no pretence that there is any real cheese involved (and those brands where the manufacturer claims that real cheese is one of the ingredients, are inferior in taste in my opinion).

Now, more than chocolate cake, I love fluorescent-orange cheesey corn puffs. In England are they are called Cheezy Wotsits (pictured right...and don’t they look delicious!). I have an insatiable appetite for these wonderful dusted pieces of crunchy manna. The dust they are coated with is 'cheese-flavoured' - there's no pretence that there is any real cheese involved (and those brands where the manufacturer claims that real cheese is one of the ingredients, are inferior in taste in my opinion).

I could happily enjoy three meals a day consisting of nothing else and never get tired of them. But I don’t do that because I know that however much I like them they are not good food…or not if you eat them in the quantities that I want to eat them anyway. I would end up overweight and have permanently colour-stained fingers and lips.

So where does this leave us in trying to decide if a work of art is good. There are no rules of beauty by which I can decide how beautiful something is on a scale of 1-10. There is no artistic expert doing the equivalent what the nutritionist has done for the Cheesy Wotsit: a scientist with beauty meter that gives a definitive answer. For all that I might use ideals of harmony and proportion when creating art, the process of apprehending beauty after the fact is always intuitive. When I see a tree, I don’t go out and measure to see if it’s beautiful. I look at it and decide that it is. It’s just like harmony in music. The composer follows the rules of harmony, but listener just listens and decides if it is beautiful.

But the fact that it is difficult to discern, doesn't mean that it is not an objective quality. It just means that I should try to be as discerning as I can. And here's how I approach this problem: because I know that the good and the true and beautiful must all exist in equal measure in any particular object, I ask myself certain pointed questions to help me judge them and only if the answer is yes will I select the piece:

Is it communicating truth? This means that I look at the content and the form (see Make the Form Conform) and ask myself if what is being communicated is consistent with a Catholic worldview. If it isn’t I reject it, regardless of whether or not I like it.

The second question I ask myself is do I think it is beautiful? If I at least try to make a judgement on beauty then at least I stand a chance of getting it right. And this probably isn't as unreliable as you might think. When I go through this process with the classes I teach I ask them if they like a piece. Very often there is a split within the class. However, when I ask the question: do you think this is beautiful? There is almost always a much higher degree of consensus. Christopher Alexander, an architect, wrote a book in which he described an experiment he carried out. He presented people with an object and then asked a range of questions and observed the degree of consensus. He found ‘do you like this’ had a low degree of consensus; ‘is this beautiful?’ was higher; and ‘would you like to spend eternity with this?’ gave almost complete unanimity. He was framing the questions so as to get people to think gradually more about the nature of beauty, and when he did, there was consensus.

And finally do I like it? So it’s not that taste is completely unimportant, but that it is just one aspect of choosing.

If the answer to all of these is yes I choose it. Even then, does this mean that I have made an infallible choice? No. As I mentioned before, there is no visible standard of perfect beauty by which I can measure something on any verifiable ‘beauty-scale’. God who is pure beauty is the standard, and I can’t see Him. However, what this does do by using reason to some degree, is to increase my chances of getting it right.

If I was choosing a piece for a public viewing, and especially a work of art for a church, I would play safe and seek not only those works that passed the above criteria when I consider my own opinion, but also for which there is a broad consensus that they are good, true and beautiful. How do I know which these are? Tradition tells me. Tradition is Chesterton’s democracy of the dead – taking the highest proportion of yesses, when considering all time, and not just the present. So for liturgical art, the authentic traditions are the styles of the iconographic, the gothic and the baroque. These styles have passed the test of time and I would choose art in these forms.

One last point, art is like food in another way. The more I am exposed to what is good, the more I learn to like it. My taste can be educated. So the more I expose myself to traditional art, the better my taste will become. Just as the more I eat salad, the more I will like it and the maybe one day I will grow out of Cheezy Wotsits...although I hope that day never comes.

Why All Christian Artists Must Learn to Draw - And Where You Can Learn To Do It Well

Summer Drawing Classes in the Academic Method at the Ingbretson Studios, Manchester NH

All figurative Christian art, and especially sacred art, is a balance between natural appearances and idealisation. Idealisation is the controlled distortion from natural appearances that enables the artist to communicate invisible truths.

Summer Drawing Classes in the Academic Method at the Ingbretson Studios, Manchester NH

All figurative Christian art, and especially sacred art, is a balance between natural appearances and idealisation. Idealisation is the controlled distortion from natural appearances that enables the artist to communicate invisible truths.

Some people assume that working in a style such as the gothic or iconographic is easier than in more naturalistic styles, but in fact to be able to work in a style well is takes great skill. The artist must be aware of span the divide between the two worlds he is representing. If there is too great an emphasis on natural appearances, then it lacks mystery. If the distortion so too great, then we lose a sense of the material. Artists should be aware too, that in sacred art the degree of naturalism should be less than in mundane art - for example landscapes and portraits.

Pius XII spoke of this in Mediator Dei (195) he refers to this balance (he uses the word 'realism' for my naturalism; and 'symbolism' for my idealism): 'Modern art should be given free scope in the due and reverent service of the church and the sacred rites, provided that they preserve a correct balance between styles tending neither to extreme realism nor to excessive "symbolism," and that the needs of the Christian community are taken into consideration rather than the particular taste or talent of the individual artist.'

The first step in getting this right is studying the tradition to develop a sense of where the balance lies. Even so, different artists will have a different sense of exactly where this balance lies, but even recognition of the fact that there can be excessive naturalism and excessive abstraction and that he should seek the temperate mean goes a long way to getting it right.

The second step is getting the skill to represent precisely both the naturalistic and the idealistic (by reflecting accurately the idea of the mind in the artist). The artist who cannot draw well from nature cannot do this, for no matter how well conceived his ideas may be he cannot represent them accurately if he cannot draw well. Therefore learning to draw well is an essential part of the training of any artist. Regardless of the style in which he ultimately intends to paint in, I would recommend everyone to learn to draw rigorously. The best drawing training that I know is the academic method. I spent a year learning this in the Florence atelier of Charles H Cecil with the blessing of my icon painting teacher even though the style is very different. As a result the quality of my icon painting went up by orders of magnitude. A danger of learning the academic technique is that of being so dazzled by how ones drawing improves that one forgets that technique is only the means to an end and not the end. The artist must realise that he cannot succeed on technique alone and so should not neglect the development of his understanding tradition and how to direct those skills in the service of God.

Those who wish to learn this technique can come along to the Thomas More College summer school art program. This is done in conjunction with the world reknowned Ingbretson Studio, featured here:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fbtBW2T50p0 In this class a day spent in the studio is supplemented by a series of lectures explaining the basis of the tradition and placing the use of it within the context of Catholic sacred art so that you always control the technique in the service of the Church.

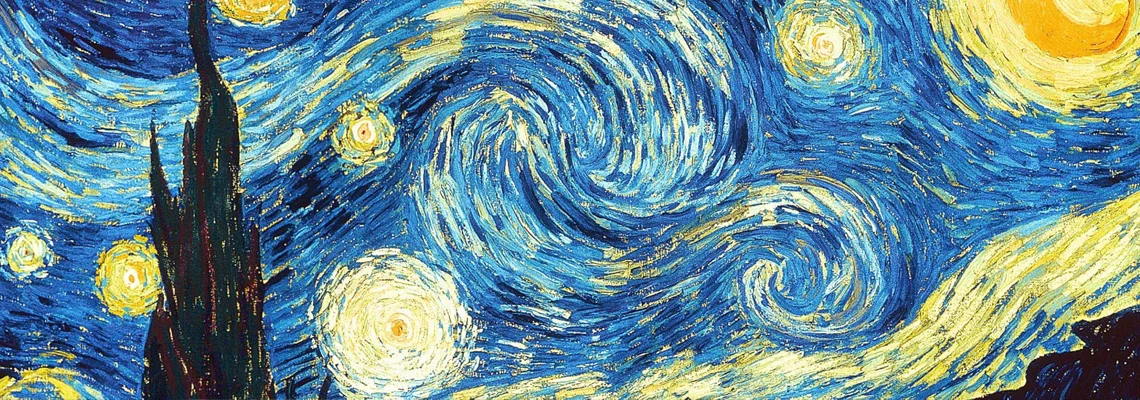

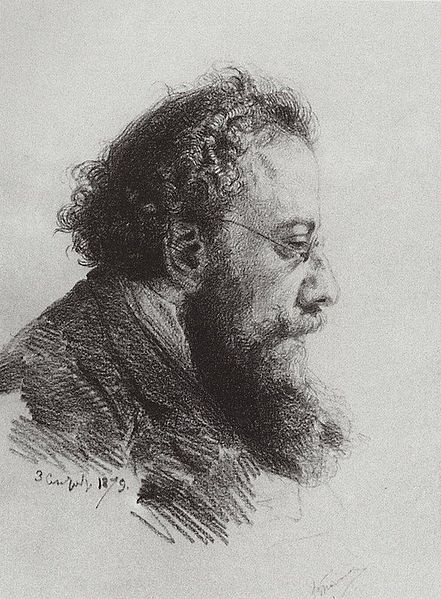

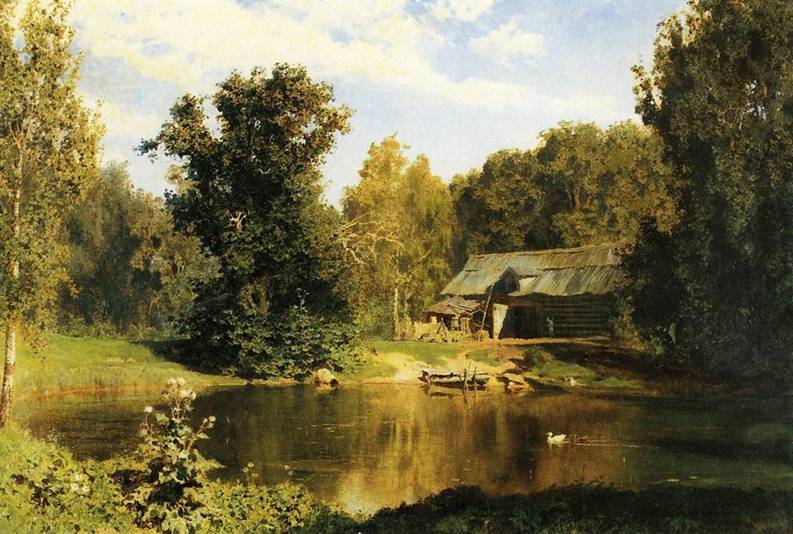

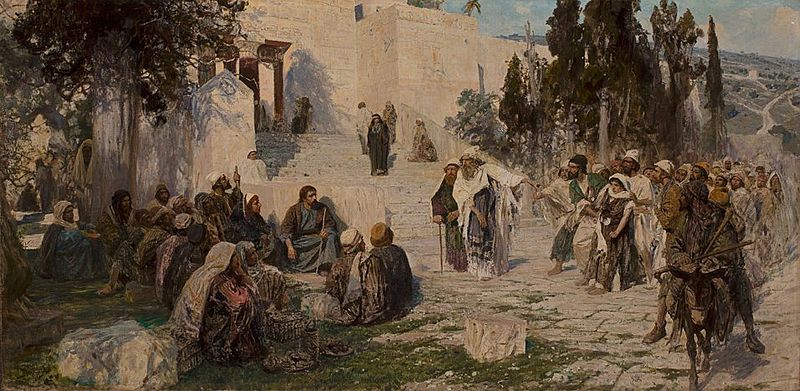

Just to illustrate the level of drawing skill achieved by the academic method. Here is work from the Russian 19th century Master Vasiliy Polenov. He is highly skilled. You can see a couple of examples of his drawings including one of a bibilical scene - the raising of the daughter of Jairus. I have also included a couple of his landscapes.

In my personal judgement, he was a superb draughtsman and has dazzling technical skill. This works wonderfully in the landscapes. However, it is not sufficiently abstracted or symbolic for sacred art and so his bibilical scenes look more like what we used to seeing as color plates in children's bibles than devotional art. It is interesting to note that in Russia in the 19th century, this is how art for churches was painted and part of process of reestablishing the Russian iconographic tradition, which happened in the 20th century as reaction to this by figures at the turn of the last century such as Fr Pavel Florensky. His analysis was then picked up by painters such as Ouspensky and Kroug in the mid-20th century.

The purpose of this not to argue against the validity of the academic training. In fact it is the opposite, I would argue that it has great value; but if one is to use it in the services of sacred art, one must be aware of how to direct that skill towards the right balance of naturalism and idealism. This is the special element, expressed in an explicitly Catholic way, is included in the classes I have described above, and which is absent from nearly all others.

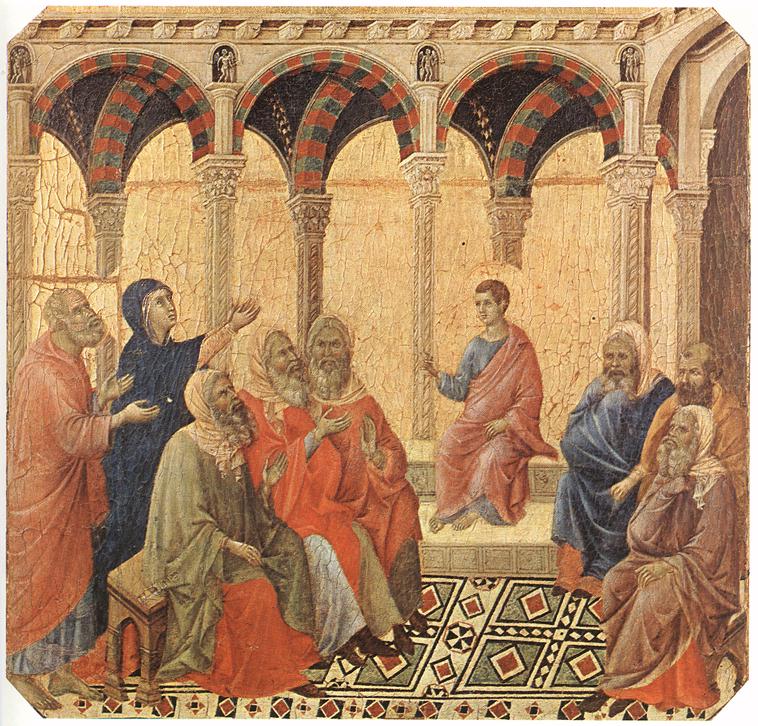

Below: first, the raising of Jairus' daughter in full, then a drawing - portrait of an art critic; a superb landscape of a Russian rural scene; then two bibilical scenes - 'he who is without sin' and the boy Jesus found in the temple teaching the teachers. By way of contrast I show Duccio's version of the same subject that has a much more abstracted style.

And here is a poster for the summer drawing class run by TMC and the Ingbretson Studios

Stations of the Cross - Some New Images in the Gothic Style

On Good Friday, here are some images for the season. A reader has directed my attention to the paintings of this London based Catholic painter. She bases here style on the 14th century Italian gothic style. I am encouraged that she is developing so well a voice, so to speak, that is characteristic of the Western tradition. I am reminded of the Florentine painter Lorenzo Monaco, whose paintings I used to see regularly in the National Gallery in London when I lived there. The link for the full set on her website is here; and to her notes on the commission here.

On Good Friday, here are some images for the season. A reader has directed my attention to the paintings of this London based Catholic painter. She bases here style on the 14th century Italian gothic style. I am encouraged that she is developing so well a voice, so to speak, that is characteristic of the Western tradition. I am reminded of the Florentine painter Lorenzo Monaco, whose paintings I used to see regularly in the National Gallery in London when I lived there. The link for the full set on her website is here; and to her notes on the commission here.

These new Stations were blessed by the Bishop of Norwich at Wymondham Abbey on Laetare Sunday.

There is one point of consideration here and that is the choice of painting the buildings in the style of 14th century Italy and some of the figures dressed in clothes contemporary to that period (we see that in the 5th station particularly. When painted, these were echoes of what the world around them looked like at that time. One might argue that today, if we were to adopt the same principle, we would be showing modern buildings and modern clothes painted in a gothic style. It is difficult to imagine, but it is the job of the artist to imagine for us. This is the talking point that I brought up recently in connection with my own work in the style of the English School of St Albans. I painted a pious knight in chainmail and wondered if I should have been painting a pious Wall Street trader in pinstripe suit as a modern equivalent!

On the other hand it might be argued that although not historically accurate representation of Palestine of 2000 years ago is nevertheless convincing to the modern viewer in regard to sacred art. We are not concerned with strict historical representation provided the principles that we do wish to convey are communicated, and the style is certainly the right balance of naturalism and abstraction that one would want to see. One could argue therefore, that it evokes another age sufficiently for us to acknowledge that this event took place historically in the past and then we move past that and on to the spiritual lessons.

Christ meets his mother

Christ's Second Fall

Christ is nailed to the cross

12th century Christian geometric art

Some readers will already be aware of the Christian tradition of geometric and patterned art (see longer articles in the section Liturgy, Number, Proportion on the archive site). This was an adaptation of the patterned geometric art that we see in the pre-Christian classical period. TMC is, in a small way. The Way of Beauty class, students reproduce some of the patterns seen at the Romanesque Cappella Palatina in Sicily.The principles behind this geometric design echo the patterns and harmonies that are the basis of proportion and compositional design in traditional architecture and art (and they are surprisingly simple to learn – you do not need special artistic ability). Although all artists would benefit from this knowledge, this is not simply an artistic pursuit. It relates to the study of the traditional education called the ‘quadrivium’.

Some readers will already be aware of the Christian tradition of geometric and patterned art (see longer articles in the section Liturgy, Number, Proportion on the archive site). This was an adaptation of the patterned geometric art that we see in the pre-Christian classical period. TMC is, in a small way. The Way of Beauty class, students reproduce some of the patterns seen at the Romanesque Cappella Palatina in Sicily.The principles behind this geometric design echo the patterns and harmonies that are the basis of proportion and compositional design in traditional architecture and art (and they are surprisingly simple to learn – you do not need special artistic ability). Although all artists would benefit from this knowledge, this is not simply an artistic pursuit. It relates to the study of the traditional education called the ‘quadrivium’.

The quadrivium, four of the seven liberal arts (geometry, music, number and cosmology), is concerned with the study of cosmic order as a principle of beauty, and which is expressed mathematically. The patterns and rhythms of the liturgy of the Church reflect this order too. Christian geometric art is an abstract (in the sense of non-figurative visual representation) manifestation of Christian number symbolism. This aspect of traditional education came from the ancients too. Pope Benedict XVI, again in one of his weekly papal addresses, described how St Boethius worked to bring this aspect of Greco-Roman culture into a Christian form of education, by writing manuals on each of these disciplines. In the medieval university, he seven liberal arts were the basis of qualification of the Bachelor of Arts (the Trivium), the Master of Arts (for the Quadrivium) and these then were the preparation for further study in the higher subjects of Theology or Philosophy, for which one could receive a Doctorate.

Geometry is not now, to my knowledge, a living tradition as a Christian art form. By the time of the Enlightenment the acceptance of number symbolism had fallen away and it died out.

I recently taught an undergraduate class about Islamic geometric patterned art at Thomas More College. This tradition, an example from a tile at the the Alhambra in Granada is shown right, is derived from the Byzantine patterned art of the lands they conquered (and of course the classical mosaics and other patterned art that preceded them). Because Islam was forbidden completely, in its strictest interpretation, from any figurative art, their focus on abstract art forms was intensified. Islamic craftsmen took what they had taken from the Byzantine craftsmen and developed it into something more complex than had previously existed.

I recently taught an undergraduate class about Islamic geometric patterned art at Thomas More College. This tradition, an example from a tile at the the Alhambra in Granada is shown right, is derived from the Byzantine patterned art of the lands they conquered (and of course the classical mosaics and other patterned art that preceded them). Because Islam was forbidden completely, in its strictest interpretation, from any figurative art, their focus on abstract art forms was intensified. Islamic craftsmen took what they had taken from the Byzantine craftsmen and developed it into something more complex than had previously existed.

The question I asked that first class was: can we safely take it back? That is, in order to reestablish this as a Christian form, can we look to the Islamic art form and re-form it into Christian tradition again?

I was pleased that in response my class said, yes. (Teachers are always pleased when their class agrees with them!) They understood further that while we can adopt some of the forms, we don’t have to adopt the Islamic numerical symbolism as well. Islamic number symbolism is similar, but crucially different from the Christian symbolism. (The number three and the Trinity come to mind immediately.) That is, it is always important to make sure that due proportion is used – that the number symbolism contained within the symmetry of the pattern is appropriate to the place where it is used, when understood in Christian terms.

For the final project of the semester I suggested to them that they consider how to incorporate some of the patterns they are learning to draw one that could be used in the floor of the sanctuary of a church. (The class in the Way of Beauty summer program will be doing something similar.)

The day after introducing the topic to the TMC students, I stumbled across this website, www.thejoyofshards.co.uk which is a great resource of images of mosaics and opus sectile work. Its gallery ranges from the floors in the offices of a Victorian architect in Norwich to Roman villas and the great churches of the world. The section on Sicilian mosaics has 80 photographs of the Palatine Chapel in Palermo. This revealed that precisely what my class was proposing had been done by the Norman king, Roger II of Sicily when he built his private chapel in the 12th century. He employed not only Christian mosaicists and Cosmati pavement specialists who produced geometric art in the Christian tradition, but also Islamic craftsmen. He instructed them to produce patterns obviously derived from those that can be seen in mosques and adapted for Christian use. This a model that would be well worth further study and I hope any architects reading this might consider commissioning something like this. I have included some photographs below of the chapel, and one pattern from a mosque for comparison; and you can see more at joyofshards.co.uk.

Below are examples of opus sectile (cut work) from the Palatina)

Is some sacred art too naturalistic?

There are many artists today working towards the reestablishment of the great naturalistic tradition of sacred art which was at its height in the 17th century, and this is to be encouraged. The artists coming out of the ateliers and studios that teach the traditional academic method who are adding greatly to this cause, and while there are some great painters of portrait and still life, I think that very often there is something wrong with the sacred art that they paint.

Someone recently asked me about this. He felt that they looked too individualised - like portraits of the person next door, which makes it difficult to identify the figure portrayed with the saint and the ideals that the saint represents. Is it possible that these modern examples of sacred art are too naturalistic he asked?

There are many artists today working towards the reestablishment of the great naturalistic tradition of sacred art which was at its height in the 17th century, and this is to be encouraged. The artists coming out of the ateliers and studios that teach the traditional academic method who are adding greatly to this cause, and while there are some great painters of portrait and still life, I think that very often there is something wrong with the sacred art that they paint.

Someone recently asked me about this. He felt that they looked too individualised - like portraits of the person next door, which makes it difficult to identify the figure portrayed with the saint and the ideals that the saint represents. Is it possible that these modern examples of sacred art are too naturalistic he asked?

I think that the answer is yes. All Christian figurative art is a balance between naturalism – likeness to physical appearances – and abstraction. The latter is the stylization that enables the artist to reveal invisible truths by visible means. We are used to a high degree of stylization in icons, but are less aware that is there too, though more subtly employed, in naturalistic sacred art too. The problem with the modern sacred art is that most people who are trained academically today are trained to paint the human person as portrait painters. The balance between naturalism and idealism is differs - what is right for portraits, is not right for sacred art.

I think perhaps the seeds of this lie in the difference between 19th century academic art, which is a degraded from of the baroque of the 17th century, which is an authentic Christian tradition (although at first glace they look similar).

Most of the best artists today who are painting in the Western naturalistic tradition were trained in ateliers that teach the academic method as it was in the 19th century. Although the techniques learnt were the same in each case, the there were subtle differences in style between 19th century naturalism (sometimes called ‘Realism’) and 17th century baroque and this reflects a difference in the ethos that underlies each. The impetus for the formation of the baroque was the Counter-Reformation, which built on the work of the great artists of the High Renaissance, which preceded it. Although not all baroque art had an explicitly sacred purpose, stylistically it had its roots firmly in the liturgical art form.

By the 19th century, the art of the teaching academies – ‘academic’ art - had become detached from its Christian ethos. So although there would be individual artists who were Catholic, it was no longer broadly accepted as a Catholic form. In this period, in regard to the painting of people, the main focus was portraiture, as this was where the money was to be made, rather than liturgical art. That is not to say that there was no sacred art all, but that portraiture became the driving force and so this is what formed the style. Characterising the difference in a nutshell: in the 17th century, you had artists whose training was directed to the painting of sacred art turning their hand to portraiture (and other mundane subjects); in the 19th century (and even more so today) you have the reverse – artists whose training is directed to portraiture (as well as still life and to a lesser degree landscape) turning their hand to sacred art.

Portrait painting, by its very nature, stresses the individual characteristic of the person. The Romantic period of the early 19th century added a new dimension. The artist was encouraged now to communicate in addition, their personal feelings about the person. This idea was not accepted by everybody immediately, but from this point we see a steady development of a sense of intimate involvement with the sitter. I do not object this to this in all cases -- I think it can work very well in portraiture. I love the portraits of the great 19th century artists (especially, for example, those of the American Boston school, which is the original source of the training I received in an atelier in Florence 100 years later). Although the unique aspects of the person are important in sacred art too, it must not be at the cost of communicating those aspects which are common to all of us. Those are the aspects of a saint that are of greatest interest to the rest of us sinners - for only the only aspects that we can emulate are those that are common to all of us.

We are made in the image and likeness of God. We are in the likeness of God in those aspects that are subject to the Fall and so can be improved with God's grace. These are the very aspects that saints reveal to us as an ideal and which are presented to us as an inspiration to do the same. In this they point to the Christ-like qualities that we should all aim to imitate. It is this idealized aspect that, in my opinion, is missing from the academic art both of the 19th century and it is even more pronounced in its current manifestation. The result in the context of sacred art is very often a painting that communicates an over-familiarity with the individual. It looks like a set from a Victorian melodrama – with a friend or relative dressed up as Our Lady, rather than Our Lady herself.

Contrast also William Bougeureau’s Virgin and Lamb [above], painted at the turn of the 20th century with Raphael’s tondo the Alba Madonna of 1511 [below].

Raphael deliberately idealized his work, to evoke the heavenly ideal, by basing it on the idealized features of ancient Greek art. Bougeureau’s Madonna, on the other hand, is tinged with a sentimentality that is, in my opinion, inappropriate for the subject which result, I believe, from this over intimate rendering of the person. However, looking another piece of work by the same artist, but this time a portrait, we see a work of both great vigour and beauty.

His style is appropriate here, I feel.

As another piece that has this staged-pose look, I would cite also Jules Bastien-Lapage's St Joan [below].

Bastien-Lepage was famous for painting rural scenes of peasants. Although rendered with dazzling skill (perhaps beyond the level of any artist I know of today) it still has the look of a model, dressed up in peasant garb rather than something that points to the saint. I would struggle to pray in front of this in a church. It is just too present and immediate. And, like Bougeureau, for all the weaknesses of this as a piece of devotional art, Bastien-Lepage's portraits are, in my opinion, splendid.

In naturalistic art it is appropriate to communicate strongly the emotions of the subject painted (in contrast with icons for example, where it is less true). We read emotions of people by looking at their faces and by gesture. It occurs to me that perhaps one of the reasons that the baroque stresses gesture so strongly is that it provides a way of communicating emotion without requiring the observer to focus there attention so strongly on the face and so hightening too much the uniqueness of the person.

So assuming we accept the analysis, how can we avoid it this problem today? I think that the answer lies in the training.

The style within a tradition has always been transmitted by the Masters we study. So, artists seeking to produce should study and copy, in the spirit of understanding, the works of the Masters of liturgical art they admire. Although I love the work of Raphael, and there are many aspects of his work I love to be able to emulate, I would not want to do so in this particular regard – if anything he swings in the opposite direction and the idealization is overemphasized for my tastes. I would go first for the great artists of baroque naturalism, for example, Georges de la Tour [below], Velazquez, Ribera and Zurbaran [below the de la Tours].

All of these artists, (the examples shown are de la Tour's St Joseph and Zurbaran's St Francis) presented saints with a balance of the individuality and idealisation that strikes the right balance. If there was a more recent artist whose sacred art succeeds, I would suggest the 20th century Italian, Pietro Annigoni. I saw his St Joseph [below] hanging in a church in Florence alongside baroque masters and despite its modern appearance in many other respects, it did not look out of place at all.

There is another aspect that could be introduced into the training of all artists that wasn’t present in the 17th century, but which nevertheless might help. Artists cannot help but be influenced by the art we have seen and we live in time in which we are bombarded by photographic imagery in all its manifestations. As a result the subtleties of the balance of the particular and the ideal that we are discussing are not easily reproduced even if we want to. I think that some exposure to a form of painting in which the idealized form is much more obvious and is clearly linked to theology would be beneficial. I would always recommend, therefore, that even an artist who eventually wants to specialize in the Western naturalistic tradition include some iconography in their foundational training. The actual experience of creating icons is more likely to impress these values upon the souls of artists so that intuitively they will include them in their own work.

How to Make an Icon Corner

Beauty calls us to itself and then beyond, to the source of all beauty, God. God's creation is beautiful, and God made us to apprehend it so that we might see Him through it. The choice of images for our prayer, therefore, is important. Beautiful sacred imagery not only aids the process of prayer, but what we pray with influences profoundly our taste: praying with beautiful sacred art is the most powerful education in beauty that there is. In the end this is how we shape our culture, especially so when this is rooted in family prayer. The icon corner will help us to do that. I am using icon here in the broadest sense of the term, referring to a sacred image that depicts the likeness of the person portrayed. So one could as easily choose Byzantine, gothic or even baroque styles.

The contemplation of sacred imagery is rooted in man’s nature. This was made clear by the 7th Ecumenical Council, at Nicea. Through the veneration icons, our imagination takes us to the person depicted. The veneration of icons, therefore, is an aid to prayer first and it serves to stimulate and purify the imagination. This is discussed in the writings of Theodore the Studite (759-826AD), who was one of the main theologians who contributed to the resolution of the iconoclastic controversy.

Beauty calls us to itself and then beyond, to the source of all beauty, God. God's creation is beautiful, and God made us to apprehend it so that we might see Him through it. The choice of images for our prayer, therefore, is important. Beautiful sacred imagery not only aids the process of prayer, but what we pray with influences profoundly our taste: praying with beautiful sacred art is the most powerful education in beauty that there is. In the end this is how we shape our culture, especially so when this is rooted in family prayer. The icon corner will help us to do that. I am using icon here in the broadest sense of the term, referring to a sacred image that depicts the likeness of the person portrayed. So one could as easily choose Byzantine, gothic or even baroque styles.

The contemplation of sacred imagery is rooted in man’s nature. This was made clear by the 7th Ecumenical Council, at Nicea. Through the veneration icons, our imagination takes us to the person depicted. The veneration of icons, therefore, is an aid to prayer first and it serves to stimulate and purify the imagination. This is discussed in the writings of Theodore the Studite (759-826AD), who was one of the main theologians who contributed to the resolution of the iconoclastic controversy.

In emphasising the importance of praying with sacred images Theodore said: “Imprint Christ…onto your heart, where he [already] dwells; whether you read a book about him, or behold him in an image, may he inspire your thoughts, as you come to know him twofold through the twofold experience of your senses. Thus you will see with your eyes what you have learned through the words you have heard. He who in this way hears and sees will fill his entire being with the praise of God.” [quoted by Cardinal Schonborn, p232, God’s Human Face, pub. Ignatius.]

It is good, therefore for us to develop the habit of praying with visual imagery and this can start at home. The tradition is to have a corner in which images are placed. This image or icon corner is the place to which we turn, when we pray. When this is done at home it will help bind the family in common prayer.

![]() Accordingly, the Catechism of the Catholic Church recommends that we consider appropriate places for personal prayer: ‘For personal prayer this can be a prayer corner with the sacred scriptures and icons, in order to be there, in secret, before our Father. In a Christian family kind of little oratory fosters prayer in common.’(CCC, 2691)

Accordingly, the Catechism of the Catholic Church recommends that we consider appropriate places for personal prayer: ‘For personal prayer this can be a prayer corner with the sacred scriptures and icons, in order to be there, in secret, before our Father. In a Christian family kind of little oratory fosters prayer in common.’(CCC, 2691)

I would go further and suggest that if the father leads the prayer, acting as head of the domestic church, as Christ is head of the Church, which is His mystical body, it will help to re-establish a true sense of fatherhood and masculinity. It might also, I suggest, encourage also vocations to the priesthood.

The placement should be so that the person praying is facing east. The sun rises in the east. Our praying towards the east symbolizes our expectation of the coming of the Son, symbolized by the rising sun. This is why churches are traditionally ‘oriented’ towards the orient, the east. To reinforce this symbolism, it is appropriate to light candles at times of prayer. The tradition is to mark this direction with a cross. It is important that the cross is not empty, but that Christ is on it. in the corner there should be representation of both the suffering Christ and Christ in glory.

‘At the core of the icon corner are the images of the Christ suffering on the cross, Christ in glory and the Mother of God. An excellent example of an image of Christ in glory which is in the Western tradition and appropriate to the family is the Sacred Heart (the one from Thomas More College's chapel, in New Hampshire, is shown). From this core imagery, there can be additions that change to reflect the seasons and feast days. This way it becomes a timepiece that reflects the cycles of sacred time. The “instruments” of daily prayer should be available: the Sacred Scriptures, the Psalter, or other prayer books that one might need, a rosary for example.

This harmony of prayer, love and beauty is bound up in the family. And the link between family (the basic building block upon which our society is built) and the culture is similarly profound. Just as beautiful sacred art nourishes the prayer that binds families together in love, to each other and to God; so the families that pray well will naturally seek or even create art (and by extension all aspects of the culture) that is in accord with that prayer. The family is the basis of culture.

Confucius said: ‘If there is harmony in the heart, there will be harmony in the family. If there is harmony in the family, there will be harmony in the nation. If there is harmony in the nation, there will be harmony in the world.’ What Confucius did not know is that the basis of that harmony is prayer modelled on Christ, who is perfect beauty and perfect love. That prayer is the liturgical prayer of the Church.

A 19th century painting of a Russian icon corner

The Iconography of the Immaculate Conception and the Litany of Loreto - A Lesson for Today from the Spanish Masters

I was recently asked about Zurburan's Immaculate Conception. I was aware of the general description of the iconography of the image, but could not interpret the details of everything that he has painted. My go-to person in these situations is Dr Caroline Farey, who once again will lead the teaching on the distance-learning diploma Art, Beauty and Inspiration run by the Diocese of Kansas City, Kansas through their Maryvale Center.

The general description comes from the teacher and father in law of Velazquez, Francisco Pacheco. He wrote a book, the Art of Painting in which he describes it. His starting point is the book of Revelation: “A great sign appeared in the sky, a woman clothed with the sun, with the moon under her feet, and on her head a crown of twelve stars,” (Revelation, 12:1-2). Pacheco wrote: 'Our Lady should be painted as a beautiful young girl, 12 or 13 years old, in the flower of her youth. She should be painted wearing a white tunic and a blue mantle. She is surrounded by the sun, an oval sun of white and ochre, which sweetly blends into the sky. Rays of light emanate from her head, around which is a ring of twelve stars. An imperial crown adorns her head, without, however, hiding the stars. Under her feet is the moon.'

I was recently asked about Zurburan's Immaculate Conception. I was aware of the general description of the iconography of the image, but could not interpret the details of everything that he has painted. My go-to person in these situations is Dr Caroline Farey, who once again will lead the teaching on the distance-learning diploma Art, Beauty and Inspiration run by the Diocese of Kansas City, Kansas through their Maryvale Center.

The general description comes from the teacher and father in law of Velazquez, Francisco Pacheco. He wrote a book, the Art of Painting in which he describes it. His starting point is the book of Revelation: “A great sign appeared in the sky, a woman clothed with the sun, with the moon under her feet, and on her head a crown of twelve stars,” (Revelation, 12:1-2). Pacheco wrote: 'Our Lady should be painted as a beautiful young girl, 12 or 13 years old, in the flower of her youth. She should be painted wearing a white tunic and a blue mantle. She is surrounded by the sun, an oval sun of white and ochre, which sweetly blends into the sky. Rays of light emanate from her head, around which is a ring of twelve stars. An imperial crown adorns her head, without, however, hiding the stars. Under her feet is the moon.'

Pacheco, through his teaching and writing, is hugely influential in the creation of the Spanish tradition of baroque naturalism, from which so many great painters emerged - Velazquez, Zurburan, Murillo, Cano, Ribera. It is particularly frustrating therefore, that only a few pages of over 700 are translated into English. This is one document that does seem worth studying if you are interested in working within the baroque tradition today. As with so much else, what he wrote and taught on this matter was followed by his Spanish followers. In regard to the Immaculate Conception, artists took his guidance for a long time afterwards, perhaps changing a few details. This version, by Zurburan follows it closely but has a red rather than a white tunic. Rather than symbolise her purity directly with white, Zurburan, chose red which is usually considered as representing humanity.

Looking first at the lower section of the painting: the palm tree on the left is the standard symbol of justice flourishing (Psalm 92:12), and also a symbol of Lady Wisdom (Sir. 24:14), consigned to Our Lady. On the right side there is a view of Seville, with its two landmarks, the Torre de Oro and Giralda Tower. Seville is depicted as a port with ship sailing towards it. Zurburan trained and lived in Seville.

On either side of the Virgin through the breaks in the heavenly cloud, there are symbols of the attributes of Mary. On the right, from the top: a flight of steps leading to a portal symbolises the Temple, and below is Mary as the Mirror of Justice. Zurburan has painted a reversed image of Mary in this mirror. In this mirror, we see ourselves as we are called to be in our Christian vocation, she presents an ideal for us, perfect exemplar of grace and virtue. I cannot see anything in the third window on the right - perhaps something has faded, or perhaps Zurburan left it blank, I don't know.

On the left, from above, are the Gate of Heaven; the Morning Star; the Ark of the Covenant, or possibly the House of Gold; and the Star of the Sea. The Ark of the Covenant, placed below the Mercy Seat in the Holy of Holies in the Temple, was God’s footstool. It contained the stones of the law, given to Moses on Mount Sinai, a sample of manna, and Aaron’s Rod. The ark then comes to symbolise Mary who bore in her womb Jesus, the New Law, our Eucharist and Aaron’s rod which budded (Numbers 17:1-8) is a type of Mary’s Child-bearing. The Morning Star symbolises the time when light is completely fresh, and when everything is still uncorrupted and pure. It is also the planet Venus and is a pagan symbol of female love now purified.

All the scenes shown in these windows correspond to Marian titles taken from the Litany of Loreto. This litany, which was approved by Pope Sixtus V in 1587, was well known in the Seville at this time. This indicates to me that this painting is intended to be used in prayer - as the Litany is recited we can look directly at this painting.

Dr Caroline Farey and I both teach the Art, Beauty and Inspiration diploma in Kansas city, taking place July 11-14, 2014. Go to the Maryvale Center website, here, for more details. In addition I will be teaching two painting courses. One the week before, and one the week after. You can sign up for either or both. If you do both, we will ensure that the second builds on what you learnt in the first. We will focus on the gothic style of illumination of the English School of St Albans, by artists such as Matthew Parris.

An article by Caroline appeared in the The Sower in April 2004

How to Pray With Visual Imagery

It is now more than three and a half years since I started this blog so first of all I would like to thank so many of you for your interest and your comments. I am currently involved in several book projects which will be published in the early part of next year - more information to come. In order to give myself time to write these, I thought I would reduce my postings to one fresh piece per week. However, it also occurred to me that many of you who read this, will not have seen much of what I posted in the first two years. In my mind, these are foundational to my thinking and shed light on much of what I write now, so I thought they would be worth repeating. So for these two reasons I thought I would replay some of these foundational posts. So for the next couple of months, I will alternate old and new. The first replay was first published in April, 2010:

When I first started painting icons I was, of course, interested in knowing as well how they related to prayer. I was referred by others (though not my icon painting teacher) to books that were intended as instruction manuals in visual prayer. I read a couple and perhaps I chose badly, but I struggled with them. One the one hand, they seemed to be suggesting some sort of meditative process in which one spent long quiet periods staring at an icon and experiencing it, so to speak, allowing thoughts and feelings to occur to me. Being by nature an Englishman of the stiff-upper-lip temperament (and happy to be so) I was suspicious of this. I had finally found a traditional method of teaching art that didn’t rely on splashing my emotions on paper, and here I was being told that in the end, the art I was learning to produce was in fact intended to speak to us through a heightened language of emotion. Furthermore, the language used to articulate the methods always seemed to employ what struck me as pseudo-mystical expressions and which, I suspected, were being used to hide the fact that they weren’t really saying very much.

When I first started painting icons I was, of course, interested in knowing as well how they related to prayer. I was referred by others (though not my icon painting teacher) to books that were intended as instruction manuals in visual prayer. I read a couple and perhaps I chose badly, but I struggled with them. One the one hand, they seemed to be suggesting some sort of meditative process in which one spent long quiet periods staring at an icon and experiencing it, so to speak, allowing thoughts and feelings to occur to me. Being by nature an Englishman of the stiff-upper-lip temperament (and happy to be so) I was suspicious of this. I had finally found a traditional method of teaching art that didn’t rely on splashing my emotions on paper, and here I was being told that in the end, the art I was learning to produce was in fact intended to speak to us through a heightened language of emotion. Furthermore, the language used to articulate the methods always seemed to employ what struck me as pseudo-mystical expressions and which, I suspected, were being used to hide the fact that they weren’t really saying very much.

So I started to ask my teacher about this and to observe Eastern Christians praying with icons. What struck me was that prayer for them seemed to be pretty much what prayer was for me. They said prayers that contained the sentiments that they wished to express to God. The difference between what they did and what I did at that time was that they turned and looked at an icon as they prayed. Also, when at home, often happily and without embarrassment they sang their prayers using very simple, easily learnt chant. Before meals, for example, the family would stand up, face an icon of Christ on the wall and sing a prayer of gratitude or even just the Our Father.