If every person is beautiful by virtue of being human, why do some people look ugly to me? (And presumably I look ugly to some people too!)

We know objectively that man is the most beautiful of God’s creatures. Every person is beautiful by virtue of being human. Yet, we don’t always see this. We can look around us and we see people whom we think are ugly, (although we might hesitate to tell anyone so). Just as with the recognition of all beauty, the lack here is in the one who looks, who cannot see all people around him as they really are, because he lacks love.

If every person is beautiful by virtue of being human, why do some people look ugly to me? (And presumably I look ugly to some people too!)

We know objectively that man is the most beautiful of God’s creatures. Every person is beautiful by virtue of being human. Yet, we don’t always see this. We can look around us and we see people whom we think are ugly, (although we might hesitate to tell anyone so). Just as with the recognition of all beauty, the lack here is in the one who looks, who cannot see all people around him as they really are, because he lacks love.

Some however reconcile this by looking for two beauties within each person, one physical and the other spiritual. Those who do so would say that if the physical beauty is lacking it is because there is a spiritual beauty that is invisible and it is this that we miss. I feel that this explanation creates a dualism – a separation of body and soul – that is wrong. As I see it, there is no inner beauty that is in contradiction with the outer ugliness; neither is there the converse an outer beauty that masks the inner ugliness. This duality is a fiction. That is not to say that there very often does appear to be such a disparity as in Oscar Wilde’s character Dorian Grey. Rather, that if this is the appearance, we know that the lack is our ability to see or our judgment of the sanctity of the person. The beauty is there in the whole person, body and soul and every person is physically beautiful. We do not see it we must look at ourselves and consider our own lack in love for that person.

When most people talk of beauty in connection with people, they are most likely to be considering sexually attractiveness. Even if we talk of those we are not sexually attracted to, we tend to make the judgment against these criteria. So I might talk of a handsome man. This does not mean that I find him sexually attractive, but that I think that women will. If I talk to those who are much younger than me or much older than me as pretty or handsome, I am usually doing so not in the context of how they appear now, but how they may in the future, or might have been in the past at their most attractive age. For example, with older people I imagine them as they were when at a younger marriageable age.

When most people talk of beauty in connection with people, they are most likely to be considering sexually attractiveness. Even if we talk of those we are not sexually attracted to, we tend to make the judgment against these criteria. So I might talk of a handsome man. This does not mean that I find him sexually attractive, but that I think that women will. If I talk to those who are much younger than me or much older than me as pretty or handsome, I am usually doing so not in the context of how they appear now, but how they may in the future, or might have been in the past at their most attractive age. For example, with older people I imagine them as they were when at a younger marriageable age.

However, in the ideal I would not consider anyone in this way at all. Only one person, in a perfect world, would appear sexually attractive to me, and that is my wife, whom God intends for me to see in this way. For me to see anyone but her in this way must involve a selfish non-loving component for it is based upon a desire to do something that is morally wrong.

There is a different love. This is one that looks with the same loving eyes with which a mother looks at her baby. I wrote recently how it has often struck me how often mothers will tell me, without a trace of irony, that their baby is the most beautiful that there is. I remember once chuckling in response and replying: ‘Yes, but every mother says that about her baby.’ ‘That’s true,’ said this mother and she said (without a trace of irony) ‘but my baby really is the most beautiful in the world.’

In fact, the mother is the one who sees this person fully. The fact that I don’t and that the mother doesn’t see everyone as beautiful as her baby is a reflection of a lack of love in respect to all other people. God sees every single one of us with the eyes of love even greater than those that a mother has for her child.

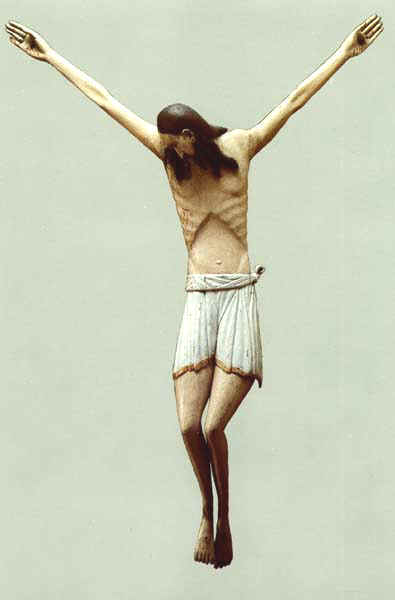

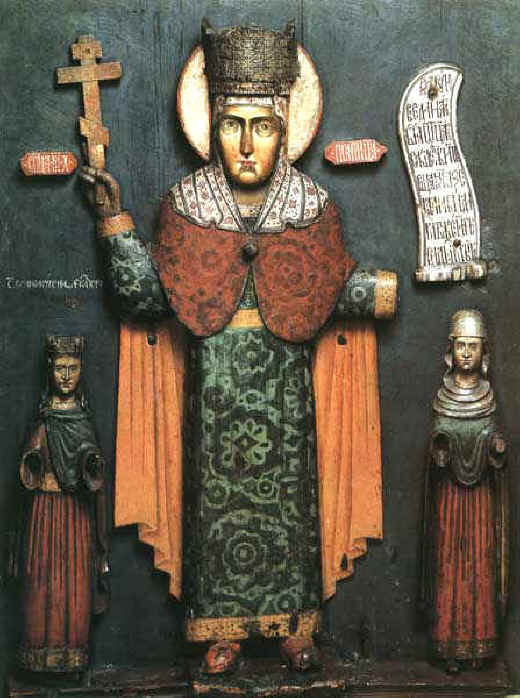

That is not to say that artists do not reveal invisible realities through a visible medium. Icons partially abstract the figure in order to do just that. The point is that these realities would be visible to all if observer and observed were both redeemed. But a painting that shows a distorted ugly human figure portrayed in a painting is not a move towards an inner reality (as an

The artist has a responsibility to represent people so that it inspires a genuinely loving response in the viewer. Consistent with this, when I was learning portrait painting in Florence my teacher always encouraged me to paint people in their best light: ‘Err towards virtue rather than vice,’ he used to say.

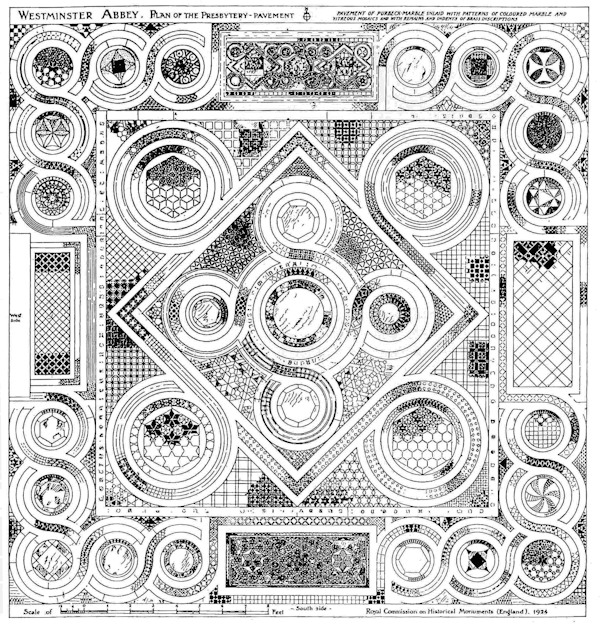

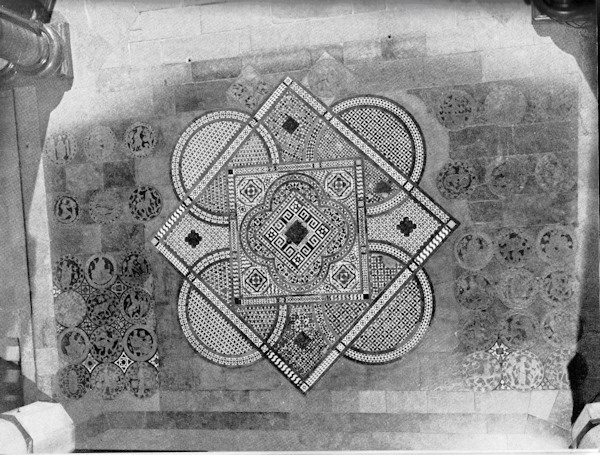

Portraits by Francis Bacon (British 20th century), repeated below; George Romney (18th century); Velazquez.