The iconographic stylization persisted in Italy in some regions due in part to the fact the some parts of Italy remained under Byzantine rule until as late as the 11th century and the painting style continued, passed down by tradition.

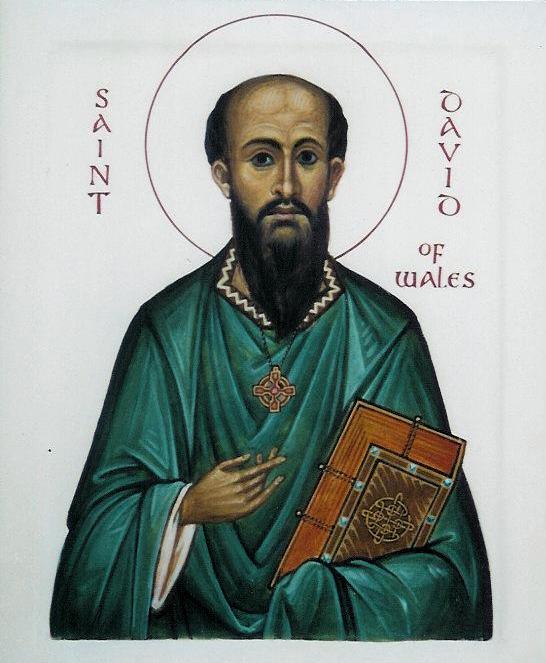

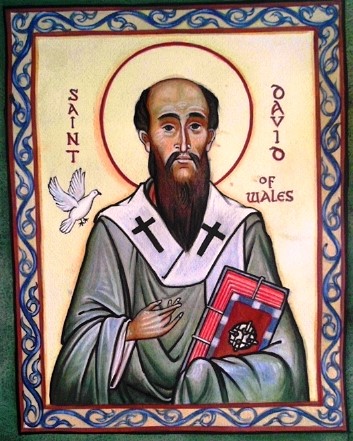

New icon, St David of Wales

This is painted in egg tempera on watercolour paper. I have based it, on another of Aidan Hart's icons of early British saints. He has done a series of similar ones to this, but I don't know if this is his own prototype or if he drew inspiration from another source. Regardless, I love his work and very often look to his corpus first when considering how to approach a subject.

This is in my icon corner at home and I noticed this morning that his right eyelid, the left as you look at it, is drooping slightly. I'll have to modify it.

This is one of the drawbacks of painting for you own prayer, you can be distracted by your own errors! Here is Aidan's:

Two Beautiful Newly Completed Icons of Western Saints by Marek Czarnecki

I have just been sent images of these two beautiful icons of St Cecilia and St Hildegard of Bingen painted by Marek Czarnecki. Marek is a Catholic iconographer based in Connecticut. (www.seraphicrestorations.com). They were another pair of commissions for Our Lady of the Mountains in Jasper, Georgia. Fr Charles Byrd the pastor and the congregation have been working together to commission a whole series of new works of art in their little church.

Don't forget the Way of Beauty online courses www.Pontifex.University (go to the Catalog) for college credit, for continuing ed. units, or for audit. A formation through an encounter with a cultural heritage - for artists, architects, priests and seminarians, and all interested in contributing to the 'new epiphany of beauty'.

Creating the New Culture of Beauty - a little parish in Jasper, Georgia shows us the way

The artistic and musical creativity of a parish shows us why liturgical and, hence, cultural renewal is likely to be a grass-roots, bottom-up process. If you want to know how your parish can do it, read this. Who is going to patronize, ie pay for, the new works that will the Catholic culture? Will it be committees created by the Vatican? Unlikely, given the evidence of the past 50 years or so. Will it be those who fund the grand cathedrals in our large cities? Possibly, but again the evidence of the recent past is not too encouraging there (although not altogether hopeless). How about the ordinary parish church? I think probably the latter. The sheer statistics point to it. There is no reason to believe that a parish priest or parish community is going to be any less (or more) aware of Catholic cultural traditions than those of cathedrals. But given that there are more parishes than cathedrals, says it is more likely that the first green shoots of cultural recovery are going to happen at the local level.

The obvious objection to this is money - where will parishes get the money to patronise the liturgical arts? Don't you need the sort of money that those who build cathedrals have to pay the artists well? I would say no. First, I do believe that artists ought to be paid at least the hourly rate we would pay any other artisan for his work (think of how much a plumber charges) which would ensure a decent price for a picture. But I say also that if the will is there it can pay for art. If a church can afford to keep the plumbing and its roof in good order; it can afford to pay reasonable prices for art and music.

I have two heartening stories about ordinary parish churches having the interest to do great work. The first is the subject of this week's story and is in Jasper, Georgia. The second is a little church in Wyoming that has decided to install a full cosmati pavement in its floor, to replace the carpeting that was there previously. I will give more detail about the second on another occasion. But today Our Lady of the Mountains, Jasper, Georgia, set, as the name suggest up in the hills, the blueridge North Georgia mountains.

I have just been contacted by Fr Charles Byrd the paster who informed me that the church had commissioned and original piece of music for their Good Friday liturgy. I'll let him tell you some detail:

'On Good Friday, 18 April 2014, at the close of Communion, the St. Gregory Choir of Our Lady of the Mountains Catholic Church in Jasper, Georgia, with soloist, Mr. Joseph McBrayer, and organist, Mr. Joseph D’Amico, under the direction of Mrs. Bridget Scott, performed for the first time ever The Song of Rood. Our relic of the True Cross, which the congregation had just venerated, was enthroned upon the altar. This recording documents that first performance. The parish had commissioned this music from Mr. Dallas Gambrell with the text loosely based upon a portion of Saint Caedmon’s epic poem, The Dream of the Rood, one of the oldest, if not the oldest, Christian texts written in English. St. Caedmon was a 7th / 8th century herdsman, lay brother, and poet, and is considered the Father of English Sacred Song. The section we used for the anthem is that part of his longer poem that had been carved in runes on the Ruthwell Cross (or rood), a standing preaching cross, in what is today southwest Scotland.'

It was sung after the Reproaches and Communion and Fr Charles tells me, may be used for the Exaltation of the Cross. You can read more about this and hear the recording of the piece (which I like very much) on their website here.

This is the same parish that contacted me and was looking to commission four icons (they commissioned two from me in the end and I referred them to another iconographer for the other two). What was noticeable to me in undertaking these is how knowledgeable and helpful he was as a patron. He had a firm idea of what he wanted, had done all the background reading on the appearances of the two saints - Ambrose and Gregory - and was clear in his mind why he wanted new images. He was open to suggestions from me as to how we might conform to his idea. As this discussion was taking place I was reminded of John Paul II's call, in his Letter to Artists, of a 'renewed dialogue' between artists and the Church. How did JPII imagine this dialogue would play out, one wonders. I can't answer that, but my own part, I don't think this is something that is going to happen at an institutional level or at grand conferences in Rome. Rather, it will right at the grassroots, where priest and congregation talk to artist and between them they produce something that will be used regularly by those who are commissioning. The great thing about the modern age is that technology, such as the internet (with media such as this blog!), ensure that remoteness does not mean isolation. Georgia and Wyoming can speak to world as easily as Rome or Washington.

Here we have someone with a great sense of the culture and the liturgy and this is what makes it. As a general rule, for a parish to be able to achieve this is needs a consensus on what is good, artistically and musically; or at least a well placed trust on the part of those who do not know, in those who do. That is the difficult part. If priest and congregation are at odds with each other it will reduce the chances of anything being done. Choosing art or music by committee which has to reconcile widely differing views by compromise, often leads to the worst of all both worlds, not the best.

Coming back to this commission: here is the description of their adaptation of the text for modern congregations: 'Our text, a modern adaptation, takes some liberties with Caedmon’s text. We augmented the text with some verses from the Vercelli Book to give this abridged poem more clarity. The original Anglo-Saxon text would be hard for us to understand today, but one phrase in that original tongue remains in our anthem — “Krist waes on rodi,” which means “Christ was on the cross.” There are two voices in the poem, the voice of the dreamer who narrates his vision, and the voice of the Holy Rood, who recalls the heroic struggle of the Crucifixion of the Lord. We can almost think of this song as a dramatic play. The chorus speaks for Caedmon and a soloist speaks the soliloquy of the Rood.

Chorus:

Hear now a vision long foretold of greatest hero from of old.

Naked He embraced the rood;

He was stripped upon the wood.

So the blessed Cross did say of Him who died for us that day.

Krist waes on rodi, Krist waes on rodi, Krist waes on rodi. Gloria.

Krist waes on rodi, Krist waes on rodi, Krist waes on rodi. Gloria.'

I give you images of the paintings commissioned from me which were delivered last Christmas as well as the recording of the music commissioned. I can't comment on the pictures (being mine) and I think the music is has the qualities of goodness of form, holiness and universality that are needed in liturgical music. Regardless, here is the point: even if you don't like what Our Lady of the Mountains has done, we can see from this example that this really can be a bottom up cultural transformation. It starts with inculturation in families and parishes who demand beautiful forms in unity with the liturgy, and beautiful worship. I don't know what the liturgy at Our Lady of the Mountains is like, but I'm guessing from the images and the music I have heard, that it is not dominated by guitars and tambourines.

From the fact that the number of parish churches is much greater

The Visitation - More Work of Students in the Style of the School of St Albans

Here's some more work from the summer painting course I taught in Kansas City, Kansas at the Savior Pastoral Center Kansas. It was sponsored by the Diocese of Kansas City, Kansas which runs the center. I thought I would show some of the work done by students. This is unusual in that we focussed on 13th century gothic illuminated manuscripts from the School of St Albans. The original is shown top left and the work of the class below. Apologies to those whose work isn't featured - I really haven't deliberately cut anyone out. For some reason I didn't arrive home with photographs of everybody's work.

We have already booked up to do two more courses next summer, so those who are interested might even contact the center now. This year the places went quickly and we could have filled the class more than twice over. The center website is here.

Here's some more work from the summer painting course I taught in Kansas City, Kansas at the Savior Pastoral Center Kansas. It was sponsored by the Diocese of Kansas City, Kansas which runs the center. I thought I would show some of the work done by students. This is unusual in that we focussed on 13th century gothic illuminated manuscripts from the School of St Albans. The original is shown top left and the work of the class below. Apologies to those whose work isn't featured - I really haven't deliberately cut anyone out. For some reason I didn't arrive home with photographs of everybody's work.

We have already booked up to do two more courses next summer, so those who are interested might even contact the center now. This year the places went quickly and we could have filled the class more than twice over. The center website is here.

At group of about a dozen adults attended the course and the level of experience varied. Some were themselves teachers of icon painting classes (who were interested in learning about the gothic style); and some were complete beginners. What was exciting for me was that all took to this western form of sacred art very naturally and were enthusiastic to keep doing it and develop this as a tradition for today. As with the work I showed recently (of St Christopher) what strikes me is how naturally the students took to this Western style. Withing a carefully controlled palette, I allowed some range of freedom in the use of colour, and encouraged them to use different borders around the painting. The ornate border is a characteristic feature of Western styles of sacred art.

I do my best to teach people so that they understand the underlying principles of what they are doing, and then they can work out things for themselves. I do stress the need for critiques of work from teachers in order to keep making progress, but at the same time, I want students to have the confidence to be able to do something on their own afterwards. So, I always try to explain why they copy precisely in some instances, and change things in others, for example. I also tell them how to examined the original painting and worked out how the artist did the original.

Why Studying Mosaics Helps Painters to Discern Colour

When I was learning to paint icons with Aidan Hart he gave us the principle of learning to paint in a particular style: 'copy with understanding'. This is true regardless of the style we wish to learn. For example, I am now focussing in the classes I teach on 13th century gothic images of the School of St Albans. I use the same principle: I look carefully, I try to understand what the artist was aiming at and then I copy. Even the great masters get things wrong and occasionally you can errors. On these occasions we don't copy the errors but try to have in mind the ideal that the artist was aiming for and correct what is there. In order to be able to make such a judgement you either need to be very knowledgeable about the tradition, or have a good teacher who can point such things out to you. The motto that Aidan used was 'think twice and paint once'. In other words, study carefully and think before you paint.

When I was learning to paint icons with Aidan Hart he gave us the principle of learning to paint in a particular style: 'copy with understanding'. This is true regardless of the style we wish to learn. For example, I am now focussing in the classes I teach on 13th century gothic images of the School of St Albans. I use the same principle: I look carefully, I try to understand what the artist was aiming at and then I copy. Even the great masters get things wrong and occasionally you can errors. On these occasions we don't copy the errors but try to have in mind the ideal that the artist was aiming for and correct what is there. In order to be able to make such a judgement you either need to be very knowledgeable about the tradition, or have a good teacher who can point such things out to you. The motto that Aidan used was 'think twice and paint once'. In other words, study carefully and think before you paint.

One thing that is sometimes very difficult to ascertain is how the colour and tone effects of a painting have been achieved. Usually what we are seeing are the combined effects of multiple transparent washes and glazes of all sorts of different tones and colours. To help us, Aidan encouraged us to look at old mosaics. The reason for this is that you can see how, for example, a flesh tone has been mixed because each constituent colour is present as a pure-coloured tessera.

Also, I can see more clearly than in a painting devices that artists use to describe form. For example, if we look at the mosaic of St Apollonarius below then we can see that the mosaicist has used all the devices that a painter is told to use on the face, but they are more obvious. So the line defining the upper lid is darker than that defining the lower eyelid. There is a dark red line between this and the eyebrow, which is the line where the eyeball goes back into the socket of the skull. There is a red line that defines the deep shadow between the hairline and the brow. Similarly, there is a red line below the end of the nose. All of these things are present in painted faces, but often they will be translucent to some degree and so the effect is more subtle and this makes it more difficult to discern what the artist did.

This mosaic, by the way was in the reliquary of a monastery that I visited recently in the US. I was told that it came originally from Ravenna! Whatever the details, it is a great piece of work.

New Icon in the Style of the 12th century St Albans Psalter

Here is a recently completed icon by the British icon painter Peter Murphy which caught my eye. It is an image of the three angels from the account of the Hospitality of Abraham and it is in the style of the St Alban's Psalter. For comparison, the curious may wish to visit the Wikipedia page of the original psalter, which dates from the first part of the 12th century, is here.

I find the images in the Romanesque period psalter very interesting because stylistically they always strike me in the design of the figures and drapery as owing something to earlier Ottonian styles of art; but also some of the faces are in profile, anticipating an element of the future gothic style. Peter has captured all of this in his work very well I think.

It is good to see an artist seeking not only to reproduce works from the period that he loves, but also seeking to produce original designs in that style. Very helpfully for me, it arrived in my Inbox just as I was writing last week's piece about how important creativity in traditional forms is if we re-establish our traditions as living traditions.

For any who wish to contact him, Peter Murphy's email is murphype@aol.com

Some Recently Completed Sacred Art

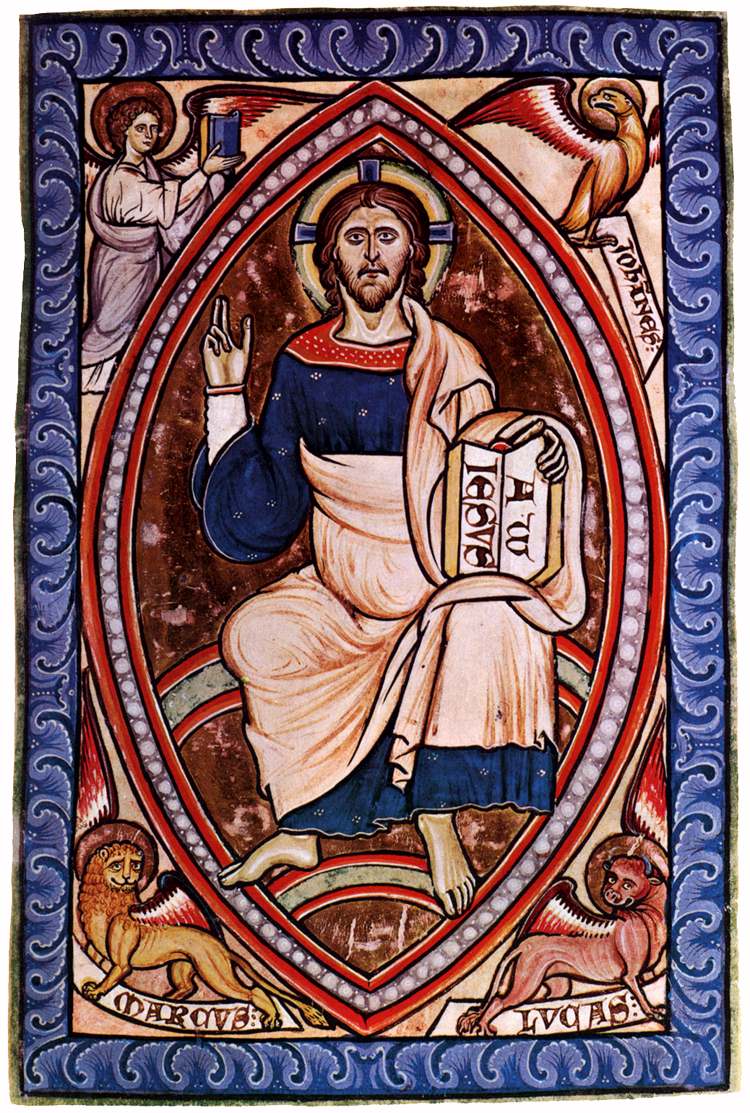

Here are two recently completed works of my own. The first is my own version of a Western iconography. It is Christ in Majesty and will go into the chapel at Thomas More College in Merrimack. I have created the basic design on a Romanesque illuminated manuscript. Christ is enthroned in heaven in glory, surrounded by the six winged seraphim and the four angels representing the four evangelists take the Word to the four corners of the world. In considering how to do this, I felt that in this the figure's sitting pose in the original is too unnatural and primitive for the modern eye. So I looked to the 20th century Russian iconographer, Gregory Kroug for the basis of the central figure. Kroug is interesting to study. Although the form is highly stylised, he was a very skilled draughtsman who placed the relative positions of limbs and torso accurately to reflect the gesture he wanted to show. The third inspiration for me is a 16th century Christ in Majesty that I saw at the Museum of Russian Icons in Clinton, Massachusetts in which the six winged seraphim who surround the throne are portrayed in monochrome in a deep green background. And finally, the face is my own style, but heavily influenced by my teacher, Aidan Hart, the British iconographer. I started this painting over the Christmas break and finished it in early May. The panel upon which it is painted is about six feet long.

Here are two recently completed works of my own. The first is my own version of a Western iconography. It is Christ in Majesty and will go into the chapel at Thomas More College in Merrimack. I have created the basic design on a Romanesque illuminated manuscript. Christ is enthroned in heaven in glory, surrounded by the six winged seraphim and the four angels representing the four evangelists take the Word to the four corners of the world. In considering how to do this, I felt that in this the figure's sitting pose in the original is too unnatural and primitive for the modern eye. So I looked to the 20th century Russian iconographer, Gregory Kroug for the basis of the central figure. Kroug is interesting to study. Although the form is highly stylised, he was a very skilled draughtsman who placed the relative positions of limbs and torso accurately to reflect the gesture he wanted to show. The third inspiration for me is a 16th century Christ in Majesty that I saw at the Museum of Russian Icons in Clinton, Massachusetts in which the six winged seraphim who surround the throne are portrayed in monochrome in a deep green background. And finally, the face is my own style, but heavily influenced by my teacher, Aidan Hart, the British iconographer. I started this painting over the Christmas break and finished it in early May. The panel upon which it is painted is about six feet long.

The second is an icon of St Victoria. I chose this subject because I painted it to give to a friend for the baptism of her baby daughter, Victoria. It is much smaller, about 10 inches long and painted on good quality watercolour paper. This took me about eight hours to paint. St Victoria according to the source I read, died in 304 and lived in Italy. When she refused marriage and to sacrifice to pagan gods because of her faith, she was martyred (that is why she is holding a cross in the icon). The guard converted because of her witness to the faith and was himself martyred.

The second is an icon of St Victoria. I chose this subject because I painted it to give to a friend for the baptism of her baby daughter, Victoria. It is much smaller, about 10 inches long and painted on good quality watercolour paper. This took me about eight hours to paint. St Victoria according to the source I read, died in 304 and lived in Italy. When she refused marriage and to sacrifice to pagan gods because of her faith, she was martyred (that is why she is holding a cross in the icon). The guard converted because of her witness to the faith and was himself martyred.

It is interesting to not that my source makes two observations. First is that very little is known about her life, and secondly that the story that we do have is 'probably a pious myth, though they did actually live'. I would love know why this final comment is made. I might be wrong, but the word 'probably' makes this sound like the historical-critical method at work to me. Historical-critical analysis is an overly skeptical form of analysis that assumes that something is untrue unless confirmed by historical evidence. So by this method, the main source of this information, which is tradition, is not accepted as a valid source of information. I prefer to work the other way around and assume that tradition is true unless proven otherwise. So in the absence of any other information I say wholeheartedly, St Victoria pray for us!

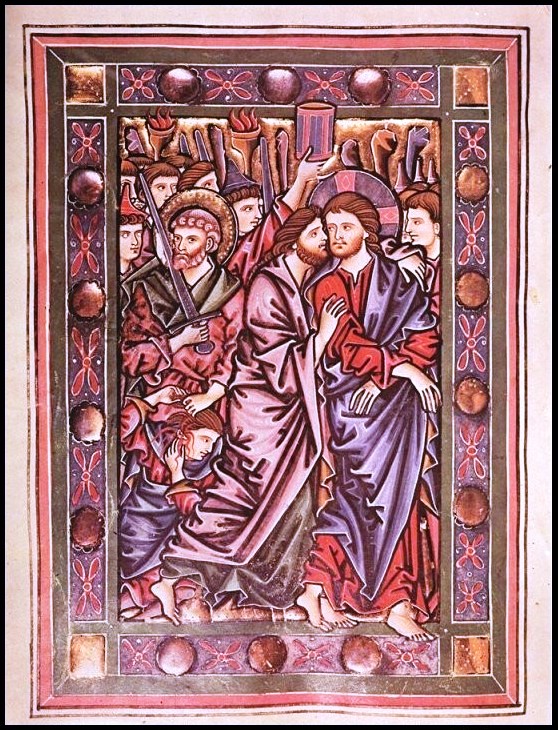

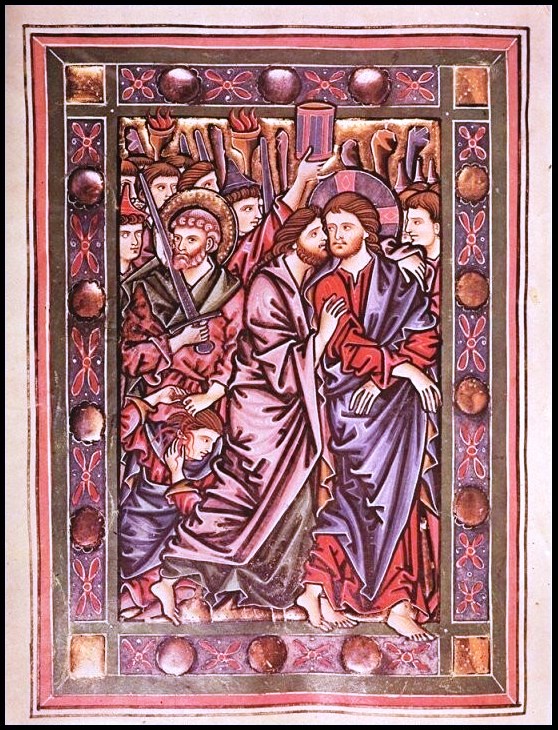

A Traditional Western Icon - from the Rheinau Psalter

How we might re-establish Catholic traditions in sacred art After my references to Western icons and also my assertion of the importance of re-establishing the gothic style as living traditions, people have been asking me to give examples of the images I am talking about. I am going to do a regular series of features of such examples in order to promote these styles. My hope is that we in the West will follow the remarkable work of the Russians and Greeks who reestablished the iconographic tradition in the Eastern Church in the middle of the 20th century (figures such as Ouspensky and Kontoglou).

The first stage in doing this is the artistic study - copying with understanding - of the works of a past tradition. And then the second stage, if this is to become a truly living tradition, is the creation of new works that are consistent with the core timeless principles of the tradition. The great achievement of our Eastern brethren is to moved through to the second stage. In the West our artistic heritage is richer (in the sense that we not only have iconographic tradition, but also the gothic and the baroque as authentic and complementary sacred art traditions). This means that in once sense, given there are three traditions, the task ahead is greater but in another, because we can follow the methods used by the Russians and Greeks (and more recently Copts with Dr Stephane Rene doing great work) it is less because we can use the principles that they used.

How we might re-establish Catholic traditions in sacred art After my references to Western icons and also my assertion of the importance of re-establishing the gothic style as living traditions, people have been asking me to give examples of the images I am talking about. I am going to do a regular series of features of such examples in order to promote these styles. My hope is that we in the West will follow the remarkable work of the Russians and Greeks who reestablished the iconographic tradition in the Eastern Church in the middle of the 20th century (figures such as Ouspensky and Kontoglou).

The first stage in doing this is the artistic study - copying with understanding - of the works of a past tradition. And then the second stage, if this is to become a truly living tradition, is the creation of new works that are consistent with the core timeless principles of the tradition. The great achievement of our Eastern brethren is to moved through to the second stage. In the West our artistic heritage is richer (in the sense that we not only have iconographic tradition, but also the gothic and the baroque as authentic and complementary sacred art traditions). This means that in once sense, given there are three traditions, the task ahead is greater but in another, because we can follow the methods used by the Russians and Greeks (and more recently Copts with Dr Stephane Rene doing great work) it is less because we can use the principles that they used.

We have made a start at this effort in cultural reform at Thomas More College of Liberal Arts and my classes there now focus on these Western forms. What is interesting is to see how the students take to these forms very happily and seem to enjoy creating them. As a result they are producing some of the best work I have seen students of mine produce. (I will post some of their work at the end of the semester once they have finished their projects). My sense is that just seems more natural to us Western Catholics to paint like images like this than to paint Eastern icons. Similarly, the Way of Beauty Summer Atelier (see here for details), which is offering an icon-painting summer school will focus on these forms, which come from illuminated manuscripts. These are excellent examples to study if you are a beginner because they are strongly line based, rather than relying on the modelling of form through gradual blening of tone and colour. This latter requires sophisticated handling of the paint which is very difficult in egg tempera, the medium used. We use egg tempera paint on high quality watercolour paper to replicate these manuscript images.

The image shown here is a remarkable plate from a 13th-century German psalter. Rheinau is the town in Germany where it was created. The artist's name is unkown. It is consistent with the iconographic prototype. The draughtsmanship is wonderful. I love the contrast between the sure smooth flow of the lines that describe the human forms, which contrast with the vigorous angular handling of those lines which describe the drapery. Artists today could learn from this, because this use of a faceting in the description of drapery helps to give the image a greater strength and less sentimental feel. Sentimentality is the scourge of modern sacred art. This device is not limited to iconographic or gothic art - even Bernini used it when he sculpted drapery in the baroque era. Note also how the Rheinau image conforms to the Western preference for patterned borders (which is not unknown but certainly less common in the Eastern variants).

Some might question the ideas this is iconographic by pointing the fact that some of the figures are in profile (not seen in icons usually). However, it seems to me that the artist is being selective in accordance with the iconographic convention. The two figures who have halos, Christ and St Peter are not in profile. All the other figures, with Judas most prominent, are part of the crowd of men who are arresting Christ. These are not saints and so this is indicated not only by the absense of halos but also by drawing them in profile.