He is a model of the New Evangelization that we can all imitate.

After his visit to the United States, the sense is that Pope Francis has done a remarkable job in connecting with people beyond the Church. True, there is constant argument about what he actually says, what people want him to say and what he really means. But despite the confusion no one can doubt that he has a knack for connecting with people. Just today, as I write this, I had a spam email from a political candidate who is, as far as I know, an avowed socialist asking me to vote for him with a connection to a speech he made praising Pope Francis because of his concern for the poor. (I am not entitled to vote for anyone in the US incidentally so he had wasted his time even if I agreed with thim). It is interesting that this should happen despite the fact that Pope Francis has repeatedly condemned socialism and a the fact the the candidate wants to use Francis to push his agenda, indicates how strong his public image is. My reaction to this was to think that this is not an argument for me to vote for socialism, as the candidate thinks; but rather one for the socialists to realise that their aims would be better met if they converted to Catholicism! Stranger things have happened!

I am presenting three articles about him to mark the occasion of his visit, sparked off by a conversation with a friend who told me that she had noticed how many of her friends, especially non-Catholics seemed to warm to him. We were asking ourselves why he is so popular. Is it really just that the non-Catholics like him because he sounds as though he is reversing Catholic teaching? I don't think so as you'll see. You will see that I am largely still optimistic about the Franciscan papacy. I do hope that I feel the same after the synod on the family which is taking place as speak :)

Two of these three contain some things I have written before, but represented in this new context.

How does he do it? The answer, I believe is quite simple and it is nothing to do with PR tactics or political spinning if ever there was a Pope that really seemed less interested and less skilled in the art of polished media manipulation it is this one. Rather, to the degree that he is connecting with people and drawing them to the truth, what is drawing people in is supernatural.

Those who do not believe in the supernatural will not account for it in this way, even if they like him, but that doesn't invalidate the point. I suggest that what we see here is a case of the New Evangelization at work. For Catholics it works like this - or rather it ought to if we followed the Church's teaching: by our participation in the sacramental life, we are transformed supernaturally so that we partake of the divine nature. By degrees in this life, and fully in the next, we enter into the mystery of the Trinity, relating personally to the divine godhead by being united to the mystical body of Christ, the Church. When this happens we shine with the light of Truth as Christ did at the Transfiguration - people see beauty and love in our daily actions because they are, quite literally, graceful. They see the joy in our lives. This is what people are seeing in Pope Francis, I suggest. And here is the great fact that so often seems to be missed, the Pope is not especially blessed in participating in this. On the contrary, what he is showing us something that is available to every single one of us, low or high. This is what he wants us to believe.

How do we get this. The place of transformation, if I can put it like that, is our encounter with God in the sacred liturgy, most especially the Mass and the Liturgy of the Hours with the Eucharist at its heart. All of the Christian life is consummated in this life by our worship of God. It is by accepting the love of God first, and most powerfully in the sacred liturgy, that we are transformed into lovers who are capable of loving our fellow man and the Franciscan way.

This message is precisely the same as Pope Benedict XVI and John Paul II before him. In this sense Francis is utterly traditional. He is, I suggest, able to be the Pope of evangelization because he comes after the work of these two great Popes who did so much, beginning with John Paul II, in the chaotic aftermath of Vatican II to implement the true message of the council. Contrary to what is often reported, he does not stand out against his predecessors. Rather, in his own way, he is in conformity with them.

Let us take the case in point. What is his view on the liturgy and the need for supernatural transformation. His words and actions indicate that he understands that all Benedict XVI did was not only necessary, but he now wants to continue in the same vein. This may be a surprise to many, but this is why I think so.

I have heard some express disappointment that there was not enough emphasis on the liturgy in the apostolic exhortation of Pope Francis, Evangelii Gaudium. It is true that there is little direct reference to the liturgy, and so it might appear at first sight that there is little interest from the Pope on this matter.

I have no special access to the personal thoughts of the Holy Father beyond what is written, so like everyone else, I look at the words and ask myself what they mean. In doing this, given that the Holy Father is for the most part articulating general principles, and given that I am not in a position to ask him directly, I am forced to interpret and ask myself what does he mean in practice? And then the next question I ask myself is this: to what degree does this change what the Church is telling me I ought to do? Or rather is he simply directing my attention to an already existing aspect of Church teaching that he feels is currently neglected?

If I want to, of course, I can choose to look at it the Exhortation as a manifesto in isolation and assume that is the sum total of all that the Pope believes; or I can choose to see this in the context of a hermeneutic of continuity. In other words I will assume that in order to understand this document, I must read read it as a continuation of those that went before, and this means most especially the period just before the advent of Pope Francis, that is, the documents of the papacy of Pope Emeritus Benedict. So unless I see something that contradicts them, I will assume that they are considered valid and important still.

If we read it this way, then because he doesn't have much to say on any particular issue, it doesn't mean that he opposes it, or even that he thinks it is unimportant, rather it means that he feels that what is appropriate has already been said and so has little or nothing to add.

This is what traditionalists within the Church say that the liberals failed to do after Vatican II. Sacrosanctum Concilium must be read, we have been told (and I think quite rightly) in the context of what went before to be properly understood; and is one reason why Pope Benedict XVI encouraged celebration of the Extraordinary Form of the Mass - so the people could learn from and experience of that context, so to speak. I accept this argument fully, and therefore, it seems reasonable to read the writings of the new Pope in this way too.

Now to Evangelii Gaudium and the liturgy. The following paragraph appears:

'166. Another aspect of catechesis which has developed in recent decades is mystagogic initiation.[128] This basically has to do with two things: a progressive experience of formation involving the entire community and a renewed appreciation of the liturgical signs of Christian initiation. Many manuals and programmes have not yet taken sufficiently into account the need for a mystagogical renewal, one which would assume very different forms based on each educational community’s discernment. Catechesis is a proclamation of the word and is always centred on that word, yet it also demands a suitable environment and an attractive presentation, the use of eloquent symbols, insertion into a broader growth process and the integration of every dimension of the person within a communal journey of hearing and response.'

So what is mystagogical initiation? What the Pope is saying seems to me be referring to and reiterating what was said in the apostolic exhortation written by Pope Emeritus Benedict, Sacramentum Caritatis. This is headed 'On the Eucharist as the Source and Summit of the Church's Life and Mission' and was written following a synod of bishops (I don't know, but I'm guessing the Pope Francis was present). In a section entitled 'Interior participation in the celebration' we have a subheading 'Mystagogical catechesis' in which the views of the gathered bishops are referred to specifically:

'64. The Church's great liturgical tradition teaches us that fruitful participation in the liturgy requires that one be personally conformed to the mystery being celebrated, offering one's life to God in unity with the sacrifice of Christ for the salvation of the whole world. For this reason, the Synod of Bishops asked that the faithful be helped to make their interior dispositions correspond to their gestures and words. Otherwise, however carefully planned and executed our liturgies may be, they would risk falling into a certain ritualism. Hence the need to provide an education in eucharistic faith capable of enabling the faithful to live personally what they celebrate.'

This is so important that the following paragraph was included also:

c) Finally, a mystagogical catechesis must be concerned with bringing out the significance of the rites for the Christian life in all its dimensions – work and responsibility, thoughts and emotions, activity and repose. Part of the mystagogical process is to demonstrate how the mysteries celebrated in the rite are linked to the missionary responsibility of the faithful. The mature fruit of mystagogy is an awareness that one's life is being progressively transformed by the holy mysteries being celebrated. The aim of all Christian education, moreover, is to train the believer in an adult faith that can make him a "new creation", capable of bearing witness in his surroundings to the Christian hope that inspires him.' [my emphases]

I don't think it is possible to make a stronger statement on the centrality of the liturgy to the life of the Church and the importance of the faithful understanding this and deepening their participation in it. There is no reason to believe that Pope Francis is dissenting from this, in fact quite the opposite - he seems to be referring directly to it and re-emphasising it. If this is what he doing, then he might be stressing the liturgy in a way that even some Catholic liturgical commentators do not. (Indeed, one wonders if the first step in mystagogical catechesis for many is one that begins by explaining the meaning of the phrase 'mystagogical cathechesis'!)

I wonder also how many Catholic colleges and universities (I am thinking here of those that consider themselves orthodox) actually make mystagogy the governing principle in the design of their curricula? How many Catholic teachers, regardless of the subject they are teaching, consider how what they are teaching relates to it? If we believe what Pope Benedict wrote (and Francis appears to be referring to) then if I can't justify what I teach in these terms, then it isn't worth teaching.

Am I choosing to interpret Pope Francis the way I wish to see it too? Perhaps - like most people I would always rather that others agreed with me than the other way round. Only future events will demonstrate if I am correct. However, his papacy so far seems to support this picture: while there are some new things, I have read nothing that that explicitly rejects anything that developed during the previous papacy (that's not to say that he hasn't said things that could be interpreted that way if we chose to). In fact, the signs seem to indicate the reverse: his appointment as the Prefect of the Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments has told us the he was directed explicitly by Pope Francis, to 'continue the good work in the liturgy started by Pope Benedict XVI,' He has broadened and strengthened the mission of the Anglican Use Ordinariate, which is all about enrishment of the liturgy in the English vernacular. I wrote about this in an article 'Has Pope Francis saved Western culture?'. And I have read articles in the New Liturgical Movement website and elsewhere heard anecdotal evidence that he has rejected direct appeals from deputations of emboldened liturgical liberals asking him to ban the Extraordinary Form and celebrating the Mass ad orientem (I attended at a papal Mass in St Peters that was celebrated by him in Latin two years ago).

His personal preferences may not be precisely the same as mine, and I will freely admit that in some of the specifics of matters where I am not bound to agree with him - matters of science and politics for example. But in but in his reinforcement of matters of the Faith, I don't hear anyone telling me that the views I had three years ago need to be changed at all. So in regard to liturgy, art, music and even free market economics (despite the alarm of many), I see nothing as yet that worries me at all...quite the opposite.

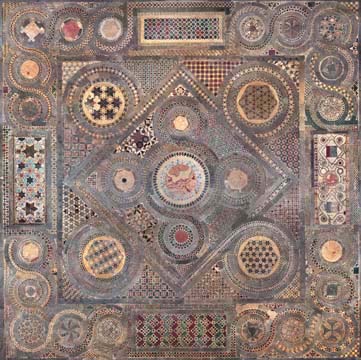

This week we show images, one is representational are and one is geometric art.

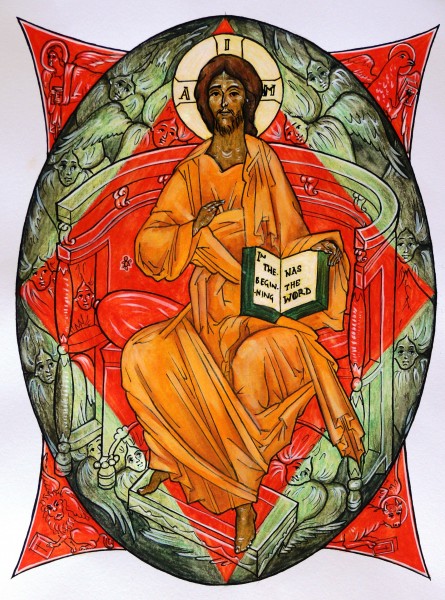

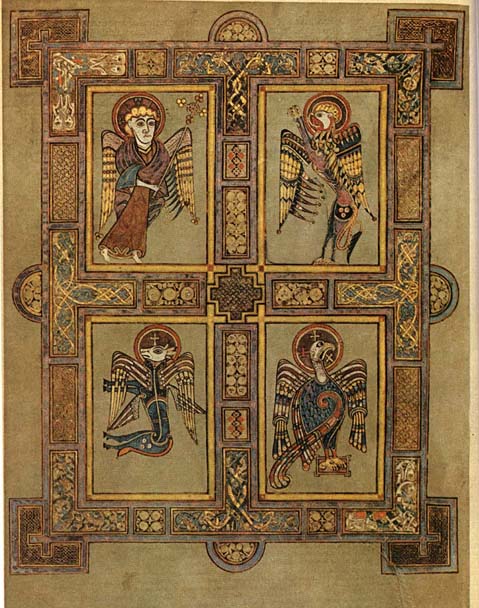

First is Christ Enthroned. I painted this for the childrens coloring book, Meet the Angels. It went on the back cover. It shows Christ, as described in the vision of Ezekiel and the Book of Revelaton, enthroned with the four faces of the Cherubim in each corner. Around the throne also are many six-winged seraphim - just wings and faces - and who are transparent so the colours of the background show through. This is a standard iconographic image and if you look on Google images for 'Christ Enthroned' or 'Christ in Majesty' you will see many in this style. It is painted in egg tempera. The almond shape around Christ is called a Mandorla (Italian for almond!) and represents the cosmos.

This week we show images, one is representational are and one is geometric art.

First is Christ Enthroned. I painted this for the childrens coloring book, Meet the Angels. It went on the back cover. It shows Christ, as described in the vision of Ezekiel and the Book of Revelaton, enthroned with the four faces of the Cherubim in each corner. Around the throne also are many six-winged seraphim - just wings and faces - and who are transparent so the colours of the background show through. This is a standard iconographic image and if you look on Google images for 'Christ Enthroned' or 'Christ in Majesty' you will see many in this style. It is painted in egg tempera. The almond shape around Christ is called a Mandorla (Italian for almond!) and represents the cosmos.