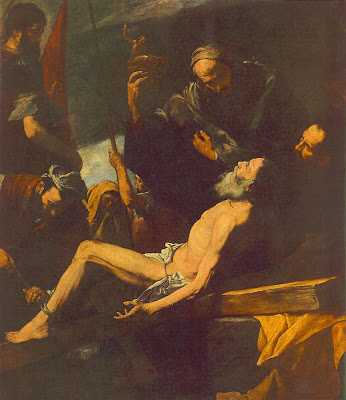

Baroque liturgical art at its best from 18th century Italy.

Bouguereau Bad, Baroque Good

Titian the trailblazer - showing us how to balance naturalism and symbolism

Titian is one of the greats of Western art. He lived from about 1480 to 1576, in Venice, and was active almost right to the end of his life. He began painting in the period of the High Renaissance and when he died was in the latter part of the 16th century which was characterized by individual artistic styles collectively called 'mannerism'. Titian's style, though individual to him when he established it, was highly influential and much of what characterized the baroque tradition of the 17th century was derived from his work. In some ways he can be considered one of the pioneers of the baroque style that dominated in the 17th century. This is important because the baroque is the one artistic traditions that Pope Benedict describes, in his book, the Spirit of the Liturgy, as being an authentic liturgical tradition.

Some people may be surprised, as I was, to discover that the High Renaissance (the style of Leonardo, Michelangelo and Raphael from about 1490 to 1525) is not considered fully and authentically liturgical (ie right for the Catholic liturgy). This is not to say that there are not individual works of art from these great artists that might be appropriate, but that it was not yet a coherent tradition in which a theology of form had been fully worked out, as was later to happen for the baroque. Pope Benedict argues that for the most part it was too strongly influenced by the pagan art of classical Greece and Rome and reveals the self-obsessed negative aspects of classical in a way that is not fully Christian.

Titian is one of the greats of Western art. He lived from about 1480 to 1576, in Venice, and was active almost right to the end of his life. He began painting in the period of the High Renaissance and when he died was in the latter part of the 16th century which was characterized by individual artistic styles collectively called 'mannerism'. Titian's style, though individual to him when he established it, was highly influential and much of what characterized the baroque tradition of the 17th century was derived from his work. In some ways he can be considered one of the pioneers of the baroque style that dominated in the 17th century. This is important because the baroque is the one artistic traditions that Pope Benedict describes, in his book, the Spirit of the Liturgy, as being an authentic liturgical tradition.

Some people may be surprised, as I was, to discover that the High Renaissance (the style of Leonardo, Michelangelo and Raphael from about 1490 to 1525) is not considered fully and authentically liturgical (ie right for the Catholic liturgy). This is not to say that there are not individual works of art from these great artists that might be appropriate, but that it was not yet a coherent tradition in which a theology of form had been fully worked out, as was later to happen for the baroque. Pope Benedict argues that for the most part it was too strongly influenced by the pagan art of classical Greece and Rome and reveals the self-obsessed negative aspects of classical in a way that is not fully Christian.

As a young man Titian trained during the High Renaissance and the influence of this can be seen in this early painting of his, the Enthronement of St Mark. At the feet of St Mark are Ss Cosmas and Damien on the left, and St Sebastien and St Roch on the right. This was painted in 1510 and one could be forgiven for thinking it was painted by Raphael. Notice how sharply defined all the figures and all the details are, even the floor tiles.

If you compare this with the following paintings we see how his work changed as he got older. The first is Cain and Abel painted in 1543; and the second is the entombment of Christ, painted in 1558. In the latter Joseph of Arimathea, Nicodemus and the Virgin Mary take Christ in the tomb watched by Mary Magdalene and Saint John the Evangelist.

We can see how, in contrast to the first painted how diffuse and lacking in color much each painting is. The edges are blurred in many places and only certain areas have bright or naturalistic color. Those areas of primary focus are painted with sharper edges and with bright colors. This is done to draw our attention to the important part of the composition. He cannot apply bright color to the figure of Christ but notice how he uses the bright colors from the clothes of the three figures who are carrying him to frame his figure. In contrast the two figures in the background are depleted of color and detail. He wants us to be aware of them, but not in such a way that they detract from the most important figure. He uses the white cloth draped over the tomb in the same way, making sure that the sharpest contrast in tone, light to dark is between this and the shadow of the tomb. They eye is naturally drawn to those areas where dark and light meet and this is how Titian draws our gaze onto Christ.

It is suggested that this looseness of style in Titian's later works occured because as his eyesight declined, he was unable to paint as precisely as he had done as a young man. This may well have been what forced him to work differently, but if so, all I can say is, my, how he accomodated his handicap so as to create something greater as a result!

If we go forward now to early 17th century Rome, it is the artist Caravaggio who is often credited with creating the characteristic visual vocabulary of exaggerated light and dark of the baroque style. We have seen deep shadow and bright light before this time, but Caravaggio exaggerated it and embued it with spiritual meaning in a new way. The shadow represents the presence of evil, sin, and suffering in this fallen world; and it is contrasted with the light which represents the Light, Christ, who offers Christian hope that transcends such suffering.

This visual vocabulary of light and dark can be seen in the painting above. Notice how it is so pronounced that in this example we do not see any background landscape; all apart from the figures is bathed in shadow. One thing that Caragaggio does retain from the visual style of the High Renaissance is that generally his edges are sharp and well defined, even if partially obscured by shadow. Other artists looked at this and while adopting Caravaggio's language of light and dark, incorporated also the controlled blurring edges that characterized Titian. What we think of as authentic baroque art is a hybrid of the two.

Look at the following painting by the Flemish artist, Van Dyck, St Francis in meditation, painted in 1632:

We can see how much he has taken from Titian in this painting. Van Dyck trained under Rubens. As a young man in 1600, Rubens travelled to Italy where he lived for eight years. His travels took him to Venice (where he saw the work of Titian), Florence and Rome (where much of Caravaggio's work was). He was influenced strongly by both and passed on these influences to his star pupil.

Sassoferrato's Virgin at Prayer - for the Nativity of the Blessed Virgin Mary

For today's Feast of the Birthday of the Blessed Virgin Mary here is the Virgin at Prayer by the Italian artist Giovanni Battista Salvi da Sassoferrato who is generally known simply as Sassoferrato. He lived from 1609 to 1685.

Records of the commemoration of the Nativity of the Blessed Virgin Mary on September 8th go back to the 6th century. The Solemnity of the Immaculate Conception of Mary was later fixed at December 8, nine months prior.

For today's Feast of the Birthday of the Blessed Virgin Mary here is the Virgin at Prayer by the Italian artist Giovanni Battista Salvi da Sassoferrato who is generally known simply as Sassoferrato. He lived from 1609 to 1685.

Records of the commemoration of the Nativity of the Blessed Virgin Mary on September 8th go back to the 6th century. The Solemnity of the Immaculate Conception of Mary was later fixed at December 8, nine months prior.

There is a commentary on the Feast from the following information is drawn, here, by Fr Matthew Mauriello: 'The primary theme portrayed in the liturgical celebration of this feast day is that the world had been in the darkness of sin and with the arrival of Mary begins a glimmer of light. That light which appears at Mary's holy birth preannounces the arrival of Christ, the Light of the World. Her birth is the beginning of a better world: "Origo mundi melioris." The antiphon for the Canticle of Zechariah at Morning Prayer expressed these sentiments in the following way: "Your birth, O Virgin Mother of God, proclaims joy to the whole world, for from you arose the glorious Sun of Justice, Christ our God; He freed us from the age-old curse and filled us with holiness; he destroyed death and gave us eternal life.

'The second reading of the Office of Readings is taken from one of the four sermons written by St. Andrew of Crete ( 660-740 ) on Mary's Nativity. He too used the image of light: "...This radiant and manifest coming of God to men needed a joyful prelude to introduce the great gift of salvation to us...Darkness yields before the coming of light."

This painting, like the painting of Gregory the Great by Vignali, described last week, is in the baroque style of the 17th century. Again, we see the sharp contrast between light and dark symbolizing the Light overcoming the darkness, and again like the Vignali, the face is in partial shadow ensuring that this is distinct in style from a portrait (I described the reasons behind this in more detail in the earlier posting). There is an additional element here in the portrayal of the face that was not so strongly present in Vignali's painting. The facial features are highly idealized and bear the likeness of the ancient Greek classical ideal.

Sassoferrato's training and influences were all in the classical baroque school. This is a stream within baroque art that looks to Raphael from 100 years before as its inspiration. Raphael's faces, in turn, strongly reflected the classical Greek ideal and this was picked up by the Caraccis in the late 16th century (most famously Annibale) who founded a school from which most of line of influential figures in the classical baroque line emerged.

Sassoferrato's training and influences were all in the classical baroque school. This is a stream within baroque art that looks to Raphael from 100 years before as its inspiration. Raphael's faces, in turn, strongly reflected the classical Greek ideal and this was picked up by the Caraccis in the late 16th century (most famously Annibale) who founded a school from which most of line of influential figures in the classical baroque line emerged.

All Christian sacred art must have a balance of idealism, which points to what we might become; and naturalism which roots the image in the particular and what we see and know in the here and now. The different styles of Christian sacred art look different from each other because they look to different sources for their ideal, and because of the exact balance of idealism and naturalism they reflect. Baroque classicism is called so to distinguish it from 'baroque naturalism' in which, though still partially idealized in accordance with what is good for Christian sacred art, has a greater emphasis on natural appearances. Ribera would be an example of the naturalistic school and Poussin was one of the most famous proponents of baroque classicism.

We can see the similarities in the facial features of the Sassoferrato Virgin, Raphael's Alba Madonna (which I describe in more detail in a posting here) and the ancient Greek statue the Venus of Arles from the Louvre. This strong idealization is another way that the artist ensures that portrayal of Our Lady is a piece of sacred art and avoids it looking like a portrait of the girl from next door dressed in historical costume.

Here is the Venus of Arles:

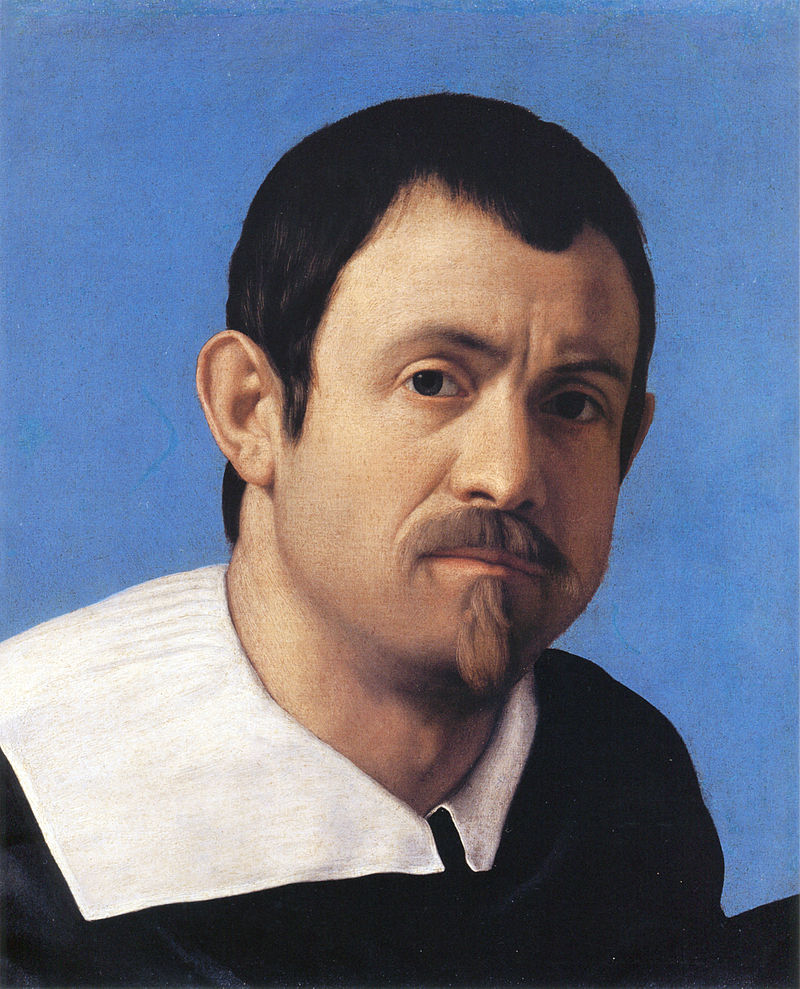

We can see the difference between the way in which sacred art and mundane art are painted by contrasting what these works with Sassoferrato's self portrait. Notice how in the portrait the image engages the viewer much more directly and we look deeply into his eyes, the deep shadow is absent and background is blue rather than black so the contrast between light and dark is not so pronounced. There is still some shadow in the face certainly - this necessary in order to describe form - but it is not so marked. Also there is not such an obvious fusion of the natural features of the face with those of the Greek ideal as we would see in the sacred art.

Sassoferrato's Virgin is in the National Gallery in London and I have a great fondness for it, even long before my conversion, it was one of those paintings that I always made a point of going to look at every time I visited the gallery. As a gallery that has no entrance fee, I often used to just drop in for 20 minutes on my way home from work, or even sometimes just to escape the rain! The peaceful repose and expression of Our Lady, which is even more apparent if you see the original, always drew me in.

Sassoferrato's Virgin is in the National Gallery in London and I have a great fondness for it, even long before my conversion, it was one of those paintings that I always made a point of going to look at every time I visited the gallery. As a gallery that has no entrance fee, I often used to just drop in for 20 minutes on my way home from work, or even sometimes just to escape the rain! The peaceful repose and expression of Our Lady, which is even more apparent if you see the original, always drew me in.

— ♦—

My book the Way of Beauty is available from Angelico Press and Amazon.

—JAY W. RICHARDS, Editor of the Stream and Lecturer at the Business School of the Catholic University of America said about it: “In The Way of Beauty, David Clayton offers us a mini-liberal arts education. The book is a counter-offensive against a culture that so often seems to have capitulated to a ‘will to ugliness.’ He shows us the power in beauty not just where we might expect it — in the visual arts and music — but in domains as diverse as math, theology, morality, physics, astronomy, cosmology, and liturgy. But more than that, his study of beauty makes clear the connection between liturgy, culture, and evangelization, and offers a way to reinvigorate our commitment to the Good, the True, and the Beautiful in the twenty-first century. I am grateful for this book and hope many will take its lessons to heart.”

The Iconography of the Immaculate Conception and the Litany of Loreto - A Lesson for Today from the Spanish Masters

I was recently asked about Zurburan's Immaculate Conception. I was aware of the general description of the iconography of the image, but could not interpret the details of everything that he has painted. My go-to person in these situations is Dr Caroline Farey, who once again will lead the teaching on the distance-learning diploma Art, Beauty and Inspiration run by the Diocese of Kansas City, Kansas through their Maryvale Center.

The general description comes from the teacher and father in law of Velazquez, Francisco Pacheco. He wrote a book, the Art of Painting in which he describes it. His starting point is the book of Revelation: “A great sign appeared in the sky, a woman clothed with the sun, with the moon under her feet, and on her head a crown of twelve stars,” (Revelation, 12:1-2). Pacheco wrote: 'Our Lady should be painted as a beautiful young girl, 12 or 13 years old, in the flower of her youth. She should be painted wearing a white tunic and a blue mantle. She is surrounded by the sun, an oval sun of white and ochre, which sweetly blends into the sky. Rays of light emanate from her head, around which is a ring of twelve stars. An imperial crown adorns her head, without, however, hiding the stars. Under her feet is the moon.'

I was recently asked about Zurburan's Immaculate Conception. I was aware of the general description of the iconography of the image, but could not interpret the details of everything that he has painted. My go-to person in these situations is Dr Caroline Farey, who once again will lead the teaching on the distance-learning diploma Art, Beauty and Inspiration run by the Diocese of Kansas City, Kansas through their Maryvale Center.

The general description comes from the teacher and father in law of Velazquez, Francisco Pacheco. He wrote a book, the Art of Painting in which he describes it. His starting point is the book of Revelation: “A great sign appeared in the sky, a woman clothed with the sun, with the moon under her feet, and on her head a crown of twelve stars,” (Revelation, 12:1-2). Pacheco wrote: 'Our Lady should be painted as a beautiful young girl, 12 or 13 years old, in the flower of her youth. She should be painted wearing a white tunic and a blue mantle. She is surrounded by the sun, an oval sun of white and ochre, which sweetly blends into the sky. Rays of light emanate from her head, around which is a ring of twelve stars. An imperial crown adorns her head, without, however, hiding the stars. Under her feet is the moon.'

Pacheco, through his teaching and writing, is hugely influential in the creation of the Spanish tradition of baroque naturalism, from which so many great painters emerged - Velazquez, Zurburan, Murillo, Cano, Ribera. It is particularly frustrating therefore, that only a few pages of over 700 are translated into English. This is one document that does seem worth studying if you are interested in working within the baroque tradition today. As with so much else, what he wrote and taught on this matter was followed by his Spanish followers. In regard to the Immaculate Conception, artists took his guidance for a long time afterwards, perhaps changing a few details. This version, by Zurburan follows it closely but has a red rather than a white tunic. Rather than symbolise her purity directly with white, Zurburan, chose red which is usually considered as representing humanity.

Looking first at the lower section of the painting: the palm tree on the left is the standard symbol of justice flourishing (Psalm 92:12), and also a symbol of Lady Wisdom (Sir. 24:14), consigned to Our Lady. On the right side there is a view of Seville, with its two landmarks, the Torre de Oro and Giralda Tower. Seville is depicted as a port with ship sailing towards it. Zurburan trained and lived in Seville.

On either side of the Virgin through the breaks in the heavenly cloud, there are symbols of the attributes of Mary. On the right, from the top: a flight of steps leading to a portal symbolises the Temple, and below is Mary as the Mirror of Justice. Zurburan has painted a reversed image of Mary in this mirror. In this mirror, we see ourselves as we are called to be in our Christian vocation, she presents an ideal for us, perfect exemplar of grace and virtue. I cannot see anything in the third window on the right - perhaps something has faded, or perhaps Zurburan left it blank, I don't know.

On the left, from above, are the Gate of Heaven; the Morning Star; the Ark of the Covenant, or possibly the House of Gold; and the Star of the Sea. The Ark of the Covenant, placed below the Mercy Seat in the Holy of Holies in the Temple, was God’s footstool. It contained the stones of the law, given to Moses on Mount Sinai, a sample of manna, and Aaron’s Rod. The ark then comes to symbolise Mary who bore in her womb Jesus, the New Law, our Eucharist and Aaron’s rod which budded (Numbers 17:1-8) is a type of Mary’s Child-bearing. The Morning Star symbolises the time when light is completely fresh, and when everything is still uncorrupted and pure. It is also the planet Venus and is a pagan symbol of female love now purified.

All the scenes shown in these windows correspond to Marian titles taken from the Litany of Loreto. This litany, which was approved by Pope Sixtus V in 1587, was well known in the Seville at this time. This indicates to me that this painting is intended to be used in prayer - as the Litany is recited we can look directly at this painting.

Dr Caroline Farey and I both teach the Art, Beauty and Inspiration diploma in Kansas city, taking place July 11-14, 2014. Go to the Maryvale Center website, here, for more details. In addition I will be teaching two painting courses. One the week before, and one the week after. You can sign up for either or both. If you do both, we will ensure that the second builds on what you learnt in the first. We will focus on the gothic style of illumination of the English School of St Albans, by artists such as Matthew Parris.

An article by Caroline appeared in the The Sower in April 2004

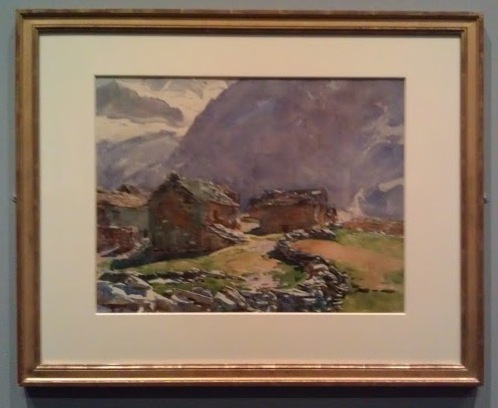

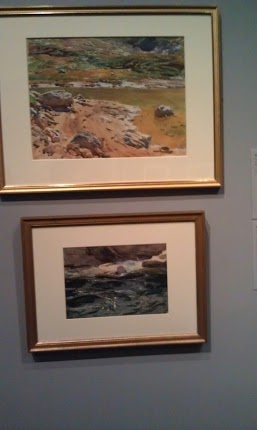

Wonderful Exhibition of Sargent Watercolours at the Boston MFA

I have just visited an exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. This is a must-see. The watercolours by John Singer Sargent display such skill and mastery directed towards such a beautiful and delightful end that I find it difficult to see how anyone could fail to marvel at them.

I always think of Sargent as the last great artist in the naturalistic tradition. He was classically trained and died in 1925. Although he knew and was influenced by the Impressionists, he never reflected their excesses in his work. He always maintained the perfect balance of looseness with close, precise focus that one would have seen in the baroque Masters 300 years earlier and was so rare even in the 19th century; and similarly difficult to find even in the atelier trained artists of today.

I have just visited an exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. This is a must-see. The watercolours by John Singer Sargent display such skill and mastery directed towards such a beautiful and delightful end that I find it difficult to see how anyone could fail to marvel at them.

I always think of Sargent as the last great artist in the naturalistic tradition. He was classically trained and died in 1925. Although he knew and was influenced by the Impressionists, he never reflected their excesses in his work. He always maintained the perfect balance of looseness with close, precise focus that one would have seen in the baroque Masters 300 years earlier and was so rare even in the 19th century; and similarly difficult to find even in the atelier trained artists of today.

Sargent was an American who was born in Florence and trained in Paris, but had strong connections throughout his life with Boston and London. He made his name as a portrait artist but around the turn of the last century abandoned portraiture because he did not enjoy it and no longer needed to paint them for financial reasons. He went on tours of Europe and North Africa and painted watercolours of what he saw. A number of these were later worked up into oil paintings, but most were not. An exhibition of his  watercolours in Boston in 1908 was so well received that the MFA bought the whole show! Spurred on by this he continued to paint them with enthusiasm. In this show we see many from that first 1908 exhibition but also many from later tours. There is even an example from his paintings of the English troops ('Tommies') during the First World War - he was employed by British War Office to record scenes of combat. Seeing this reminded me of a visit to the Imperial War Museum in London where, hanging on the wall close to guns, Spitfires and Hurricanes on display there is a huge oil painting, (8ft x 20ft) of gassed and blinded troops being lead, hand in hand in a line, from the field of combat.

watercolours in Boston in 1908 was so well received that the MFA bought the whole show! Spurred on by this he continued to paint them with enthusiasm. In this show we see many from that first 1908 exhibition but also many from later tours. There is even an example from his paintings of the English troops ('Tommies') during the First World War - he was employed by British War Office to record scenes of combat. Seeing this reminded me of a visit to the Imperial War Museum in London where, hanging on the wall close to guns, Spitfires and Hurricanes on display there is a huge oil painting, (8ft x 20ft) of gassed and blinded troops being lead, hand in hand in a line, from the field of combat.

At this exhibition we were allowed, in accordance with the modern trend in exhibitions which is so heartening, to take photographs. Below I show the photos I took with my cell phone. I have produced a series of photos where you can see the whole painting, and then details, so you can get a sense of how he combines loose and expressive brushwork with more tightly controlled use so expertly. The details were taken separately with the phone just a few inches from the surface of the painting. I suggest that you just marvel at how the image pops out of what appears (deceptively) to be such casually applied paint.

Lessons from Our Lady of Sorrows on our Response to the Suffering of those we Love

The model of loving compassion for others who are suffering. September the 15th was the Feast of Our Lady of Sorrows. I found the liturgy of the Church on this day very instructive and inspirational. The message I get from this is for me, powerful, vigorous and inspiring. The writing of St Paul and St Bernard on the matter speaks of virtue in the fullest sense of the word.

It is interesting to me that so much modern devotional art of Our Lady of Sorrows - Mater Dolorosa - is, to my eye, almost all sentimental and weak. The Spanish baroque and the Flemish gothic masters are for me the model of portraying negative emotion transcended with joy that is powerful yet calm.

The model of loving compassion for others who are suffering. September the 15th was the Feast of Our Lady of Sorrows. I found the liturgy of the Church on this day very instructive and inspirational. The message I get from this is for me, powerful, vigorous and inspiring. The writing of St Paul and St Bernard on the matter speaks of virtue in the fullest sense of the word.

It is interesting to me that so much modern devotional art of Our Lady of Sorrows - Mater Dolorosa - is, to my eye, almost all sentimental and weak. The Spanish baroque and the Flemish gothic masters are for me the model of portraying negative emotion transcended with joy that is powerful yet calm.

One of the most difficult things to deal with in life is the grief we feel when someone whom we love is suffering and we are powerless to do anything about it.

My experience tells me that this can have two components. That born of self-centredness, which is a bad feeling; and one born of love, which is opens the door to intense joy. It is this latter point that has come home to me through the liturgy on this feast day by pointing to the model of Our Lady.

When I am driven by self-centredness, I look at the person who is suffering and I feel sorry for myself. This self-pity can be intense and almost unbearable as long as I see the other's suffering as the cause of my anguish. The cause is my personal response, and I have some control over that. It is easy to decieve myself and think that this is an expression of love, but such empathy can very easily be rooted in self-centredness and be profoundly destructive to my life, while doing nothing to help the other person either. If I put myself in the other person's shoes through my imagination, I might do this so vividly that I feel sorry for myself. At a mild level this is why I feel embarrassed for someone if he makes a fool of himself in front of many people. I am not so much concerned for him, but rather imagining myself in his position so that I feel the self-pity that I would feel if I were in his shoes. Hence the discomfort.

At a deeper level, when someone we love is the author of his own suffering, perhaps an alcoholic or a drug addict, then our suffering can be driven not so much by the loving reaction of ‘how can you do this to yourself?’ but rather, ‘how can you do this to me?’. If there is a sense that the suffering is as a result of fate, then we can find ourselves directing that resentful complaint to God.

One way of dealing with this that I have heard of is to stop the habit of imagining ourselves in the shoes of the other. This is not always a good thing. A cold, uncaring detachment is heartless and shuts out all joy in our lives too. It is a response that lacks both empathy and sympathy.

There is a different sort of detachment in which we do not empathise, but we do sympathise with the suffering and act with love. So we act lovingly towards the other, but do not share in the emotions that they are experiencing as we do it. I have heard this described by some as ‘detaching with love’. Certainly this is greatly preferable to the self-centred anguish that causes us to feel sorry for ourselves when others are suffering. For many of us this may be the best approach for us to aim for, particularly if we are trying to break out of the bad habit of an instinctive reaction of a self-pity – empathy based upon self-centredness - to the suffering of others. When we become aware of the root of our emotions, it is certainly possible to develop an habitual attitude of mind that corresponds to this. In the ideal however, this would be a route to another, higher response which is one of a loving empathy. This is where Our Lady is the model.

There is a different sort of detachment in which we do not empathise, but we do sympathise with the suffering and act with love. So we act lovingly towards the other, but do not share in the emotions that they are experiencing as we do it. I have heard this described by some as ‘detaching with love’. Certainly this is greatly preferable to the self-centred anguish that causes us to feel sorry for ourselves when others are suffering. For many of us this may be the best approach for us to aim for, particularly if we are trying to break out of the bad habit of an instinctive reaction of a self-pity – empathy based upon self-centredness - to the suffering of others. When we become aware of the root of our emotions, it is certainly possible to develop an habitual attitude of mind that corresponds to this. In the ideal however, this would be a route to another, higher response which is one of a loving empathy. This is where Our Lady is the model.

The highest response to the suffering of others is a compassionate grief; and this one that is transcended by joy. This is the grief felt by Our Lady at the foot of the cross as she gazed at her suffering Son. It is an anguish born of love and as with all that arises from love it opens our hearts so that we can have a fuller union with God and experience an even greater joy.

In order for me to try to understand this, I had first to consider the situation when I am the one who is suffering directly, rather than worrying about the suffering of another. I know that God always gives us grace to deal with any situation and through cooperation with His grace, we can transcend any injustice and any suffering. When this occurs the suffering is not necessarily removed, but is as likely to be overwhelmed by the sheer joy of experiencing God’s consoling love. The writings of the saints indicate just how powerful this joy in suffering is. In order to experience this, I must first remove any self-centred feelings and resentment that I may have.

If that consolation is there for us when we are experiencing suffering directly, then it is there too when we experience pain or injustice indirectly, arising from and empathetic sharing in the suffering of others.

However, this is true only to the degree that our anguish arises from love. It if arises from a self-centred desire to right the suffering of others then we shun God’s grace. We must first free ourselves of that resentful attitude and to do this one might have to go back a step and adopt the ‘detach with love’ approach. When our anguish is a sharing in the suffering of others born of love for them, then it is a sharing also in Christ’s suffering on the cross. It is holy suffering that opens the door to a greater joy.

The Church’s liturgy on the Feast of Our Lady of Sorrows is very instructive on this. In the readings of the day there is a long passage from a sermon of St Bernard of Clairvaux. He describes Our Lady’s anguish at the foot of the cross as real, but arising from a genuine compassion that is born of charity ie love. He calls it a ‘martyrdom of the soul’: “We rightly speak of you as more than a martyr, for the anguish of mind you suffered exceeded all bodily pain.'Mother behold your son!' These words were more painful than a sword thrust for they pierced your soul and touched the quick where the soul is divided from the spirit. Do not marvel brethren, that Mary is said to have endured a martyrdom in her soul. Only he will marvel who forgets what St Paul said of the Gentiles that among their worst vices was that they were without compassion. Not so with Mary! May it never be so with those who venerate her. Someone may say: ‘Did she not know in advance that he Son would die?’ Without a doubt. ‘Did she not have sure hope in his immediate resurrection?’ Full confidence indeed. ‘Did she then grieve when he was crucified?’ Intensely. Who are you brother, and what sort of judgment is yours that you marvel at the grief of Mary any more than that the Son of Mary should suffer? Could he die bodily and she not share his death in her heart? Charity it was that moved him to suffer death, charity greater than that of any man before or since: charity too moved Mary, the like of which no mother has ever known.’(From the Office of Readings, Feast of Our Lady of Sorrows)

The Church’s liturgy on the Feast of Our Lady of Sorrows is very instructive on this. In the readings of the day there is a long passage from a sermon of St Bernard of Clairvaux. He describes Our Lady’s anguish at the foot of the cross as real, but arising from a genuine compassion that is born of charity ie love. He calls it a ‘martyrdom of the soul’: “We rightly speak of you as more than a martyr, for the anguish of mind you suffered exceeded all bodily pain.'Mother behold your son!' These words were more painful than a sword thrust for they pierced your soul and touched the quick where the soul is divided from the spirit. Do not marvel brethren, that Mary is said to have endured a martyrdom in her soul. Only he will marvel who forgets what St Paul said of the Gentiles that among their worst vices was that they were without compassion. Not so with Mary! May it never be so with those who venerate her. Someone may say: ‘Did she not know in advance that he Son would die?’ Without a doubt. ‘Did she not have sure hope in his immediate resurrection?’ Full confidence indeed. ‘Did she then grieve when he was crucified?’ Intensely. Who are you brother, and what sort of judgment is yours that you marvel at the grief of Mary any more than that the Son of Mary should suffer? Could he die bodily and she not share his death in her heart? Charity it was that moved him to suffer death, charity greater than that of any man before or since: charity too moved Mary, the like of which no mother has ever known.’(From the Office of Readings, Feast of Our Lady of Sorrows)

Following this is a quote from St Paul in his Letter to the Colossians in which he says directly that this sharing in Christ’s sufferings through love is a source of happiness: ‘It is now my happiness to suffer for you. This is my way of helping to complete, in my poor human flesh, the full tale of Christ’s afflictions still to be endured, for the sake of his body which is the Church.’(Col 1:24-25).

The antiphon for the Benedictus on Lauds for that day echoes this and takes it even further: ‘Rejoice grief stricken Mother, for now you share in the triumph of your Son. Enthroned in heavenly splendor, you reign as queen of all creation.’

The idea of 'bright sadness' is often associated with the expression of saints in icononographic art. This ideal of a loving grief in response to the suffering of another is, it seems, a bright sadness or perhaps even a peaceful anguish – an anguish burning with the fire of love that overwhelms and transcends all before it and gives an intense joy. The first painting is 17th century by Ribera, the next three are 15th century Flemish by Dirk Bouts except for the third which is by Rogier Van Der Weyden. The next two are by Ribera and Murillo and are 17th century baroque; the final one is by El Greco, who although earlier - 16th century - conforms to baroque form in this painting.

In both sets the artist is showing constraint in portraying emotion, it is there, but there is a strong sense of peace in the expressions of Our Lady in each case.

The Cosmos is Made for Man - How this Affects the Way We Paint It

The Office of Readings for July 30th, the Feast of St Peter Chrysologus contains the following passage from one of his sermons: 'Man, why do you have so low an opinion of yourself, when you are so precious to God?...Has not the household of the whole universe which you see been made for you? For you light is produced to dispel the surrounding darkness; for you the night is regulated; for you the day is measured out; for you the sky shines with the varied brilliance of sun, moon and stars; for you the earth is embroidered with flowers, groves and fruit; for you is created a beautiful, well-ordered and marvellous multitude of living things, in the air, in the fields, in the water, lest a gloomy wilderness upset the joy of the world.'He was writing in first half of the 5th century AD. This idea that the universe is made for man to see, and its corollarary, that man is made to see it governs how we paint in the naturalistic artistic traditions. The stylistic elements of baroque naturalism are generated from an analysis of how we observe the natural world and how this manner of observation of the beauty of creation, leads us to give praise to the Creator. If the work of man, in this case a painting, participates in the beauty of the cosmos then it too will raise the hearts and souls of those who see it to God through its beauty. By incorporating traditional harmony and proportion into compositional design, the artist or architect is creating something that participates in this cosmic beauty, described numerically. Similarly, by painting in such a way that stimulates a response in the way we observe it, which is the same as our reaction to the natural world, it is likely to raise our hearts and minds to God just as the beauty of creation does.

The Office of Readings for July 30th, the Feast of St Peter Chrysologus contains the following passage from one of his sermons: 'Man, why do you have so low an opinion of yourself, when you are so precious to God?...Has not the household of the whole universe which you see been made for you? For you light is produced to dispel the surrounding darkness; for you the night is regulated; for you the day is measured out; for you the sky shines with the varied brilliance of sun, moon and stars; for you the earth is embroidered with flowers, groves and fruit; for you is created a beautiful, well-ordered and marvellous multitude of living things, in the air, in the fields, in the water, lest a gloomy wilderness upset the joy of the world.'He was writing in first half of the 5th century AD. This idea that the universe is made for man to see, and its corollarary, that man is made to see it governs how we paint in the naturalistic artistic traditions. The stylistic elements of baroque naturalism are generated from an analysis of how we observe the natural world and how this manner of observation of the beauty of creation, leads us to give praise to the Creator. If the work of man, in this case a painting, participates in the beauty of the cosmos then it too will raise the hearts and souls of those who see it to God through its beauty. By incorporating traditional harmony and proportion into compositional design, the artist or architect is creating something that participates in this cosmic beauty, described numerically. Similarly, by painting in such a way that stimulates a response in the way we observe it, which is the same as our reaction to the natural world, it is likely to raise our hearts and minds to God just as the beauty of creation does.

These considerations are only relevant when we are considering the natural observation of the world we live in now. The baroque tradition is one of these as it seeks to portray fallen man, ie 'historical' man, in such a way that his potential for sanctity through cooperation with God's grace is emphasised. It aims to give us hope that transcends any evil and suffering. This does not apply to artistic traditions that are trying to communicate something different, such as the iconographic which seeks to communicate eschatological man, mankind in union with God partaking of the divine nature.

How do we observe the natural world? When we look at the world around us the eye roves around the scene before it. At any moment on only the central part of the vision is in focus and coloured - to an angle of vision of about 15 degrees. Peripheral vision is monochrome - reflecting only tonal information, no colour - and blurred. This is the nature of the image that is on the retina at any moment. But this is not what we see in our mind's eye. The memory supplies additional information to complete the scene. Usually the information is given to the memory by prior observation of different parts of the same scene. For example, if I am talking to somebody. I spend most of the time looking at the face, most particularly the eyes and eyebrows, because they communicate most information about what the person is thinking and feeling. Other than that I would make the occasional cursory glance up and down the person and unless something unusual particularly catches my attention, I focus first on the eyes, then the mouth and the gesture of the hands. All of these communicate thought. The soul is revealed through the body.

Similarly when I look at the broader scene I naturally focus on points that interest me and these will reflect, generally, the hierarchy of being. I look first and longest at any people, second at any man made objects, such as buildings, then at animals and finally at plants. Of course unusual sights will cause me to look at things longer - if I saw a two-headed sheep, then I would probably focus a lot of my attention on that.

How does the painter make use of this? He supplies key focal points of interest in the painting, harmoniously placed relative to each other and on these focal points he gives most detailed and coloured information. The rest he depletes of colour and softens the focus. In order to make sure that the eye is attracted to these key points the artist not only provides more detail, and more colour, but also will introduce into the composition something that will attract the eye immediately. Generally there will be a heightened and sharpened contrast between light and dark at the key points, and the brightest colour, perhaps a red to draw the eye.

When the focal points arranged by the artist correspond to those foci that we would have looked at preferentially when presented with a scene, because they conform to the hierarchy of being for example, then viewing the work is a delight. We are given most information in those aspects that we would be most naturally interested in anyway and we are barely aware that this is what is going on. The observation of the painting is so natural.

If the artist seeks to overturn our natural curiousity by painting, for example, a cigarette butt on the floor every bit as detailed as the person standing beside it (as a photorealist would do), then we feel overloaded with detail and information and it creates a tension as we observe the painting.

However, one would not want to give that this hierarchy of observation is a rigidly defined set of rules that allow no room for manouvre. The skilled artist understands how much leeway there is and will (through these devices of variation in focus, contrast and colour) deliberately pique our interest in things he wants us to notice by directing us to them prefentially; or conversly play down details that otherwise we might be more interested in.

The contrast between portraiture and sacred art demonstrates this point. In a portrait, the aim of the artist is to demonsrate the uniqueness of the person. By a strong emphasis on the face of the individual the artist not only communicates the thoughts and feeling of the person, thereby communicating the fact that this human person is body and soul; but also he communicates the unique characteristics of the person which for most of us are most striking in our faces. These unique characteristics are the things that differentiate us from all other humanity.

If the artist is portraying a saint or Christ, then the task is slightly different. Certainly the artist must represent the characteristics of the person that identify him as unique. But there is an important need also to emphasise those aspects of the person that can be emulated by us, these are the general characteristics of a good man - virtue, holiness and so on. This is why we look to the lives of the saints. For this reason, the baroque sacred artist, relative to a portrait painter, plays down the facial features. So very often the face will be wholly or partially in shadow, while the thoughts and feeling are communicated through the gesture and posture. The whole person is emphasised. When I was learning in Florence, my teacher Matthew James Collins made this point to me directly in contrasting the aims of portrait painting, which we studied each morning, with figure painting, which we studied in the afternoon. The figure, he told me, should have the light moving up and down its length - particularly on the broader masses such as the thighs and torso, as this emphasises the whole person and this is what the baroque tradition sought to do.

I have shown examples of portraits and paintings of saints to illustrate the point, but what the artist is doing in order to emphasise the general aspects of humanity is not always so obvious. The effect of failing to do it is more obvious. Rather than convincing us that this is the Virgin Mary or Christ, painting looks like painting of the girl or boy next door posing in costume.

This ability to partially abstract the painting in accordance with our natural way of observing, even more than a lack of technical painting skill, is in my opinion what distinguishes the masters of the past from so many atelier trained artists of today. This visual language was developed out of a Christian understanding of the relationship between the human person and the cosmos. While it is possible to consider simply it as a traditional form, without linking it to a Christian ethos, and still paint well (John Singer Sargent, for example, was not a man of faith, to my knowledge), any artist is going to increase his chances of doing so, I would suggest, if he understands and accepts the end to which all of this is directed and how these stylistic elements conform to that end.

The landscape above is by Rubens. All the paintings below are by Ribera: the Lamentation over the Dead Christ, St Andrew, the Martyrdom of St Andrew and St Peter. These should be contrasted with portraits by him that follow: the Drinker, Girl with Tambourine and Clubfooted Boy.

Noli me tangere

A comparison of the baroque naturalism of Alonso Cano and the baroque classicism of Anton Mengs After last week's comparison of two paintings of Christ's Entry into Jerusalem, this week as an Easter meditation I offer something similar, but this time each painting is of the scene when Mary Magdalen sees Christ in the garden and he tells her not to touch him - noli me tangere.

This time the offerning in baroque naturalism comes from Alonso Cano, the 17th century Spanish artist who had the same teacher as Velazquez, Francesco Pacheco. Cano is perhaps more well know for his wood carvings in polychrome (ie painted in many colours). The baroque classicist painting of the same subject is done by the German artist of the 18th century called Anton Raphael Mengs.

A comparison of the baroque naturalism of Alonso Cano and the baroque classicism of Anton Mengs After last week's comparison of two paintings of Christ's Entry into Jerusalem, this week as an Easter meditation I offer something similar, but this time each painting is of the scene when Mary Magdalen sees Christ in the garden and he tells her not to touch him - noli me tangere.

This time the offerning in baroque naturalism comes from Alonso Cano, the 17th century Spanish artist who had the same teacher as Velazquez, Francesco Pacheco. Cano is perhaps more well know for his wood carvings in polychrome (ie painted in many colours). The baroque classicist painting of the same subject is done by the German artist of the 18th century called Anton Raphael Mengs.

Baroque classicism (as exemplified here by Mengs) seeks to evoke more a sense of the classical heritage of Western culture and, inspired by Raphael the artist of 100 years before, often look as thought they are staged scenes from a Shakespeare play set in ancient Rome. Stylistically, there is always more colour and the edges are sharper and cleaner - sometimes this can tend to give them a more sterile and less lively feel, although I don't get this feeling with Meng's painting shown here. In contrast the baroque naturalist style use monochrome and broad focus much more and has a more vigorous, spontaneous feel. My preference generally is for baroque naturalism although I in this case I like both examples equally. To the modern eye, although once pointed out we can distinguish between the two streams, they still look similar. At the time though, each school thought of itself as very different from the other. Each saw theirs as the more authentic form of sacred art and and would be openly rude and dismissive about the other.

After the Englightenment the two streams of baroque art separated and became the Romantic and Neo-Classical movements. The developments, although subtle, were nevertheless destroyed the baroque and with it an authentic Christian tradition in sacred art.

Paintings: above and bottom, Anton Raphael Meng; immediately below: Alonso Cano

Christ's Entry into Jerusalem

The baroque naturalism of Van Dyck and the baroque classicism of Orente compared. We are now in Holy Week. To help our contemplation, here are two different paintings of the Palm Sunday scene - Christ's Entry into Jerusalem. Both are by 17th century painters from the heyday of the baroque period. The first is by Sir Anthony van Dyck, who was taught by Rubens and works in the baroque naturalism style (other painters in this form would be, for example, Velazquez or Zurbaran). The second is by lesser know Spanish artist who was trained by El Greco called Pedro Orrente. He painted this is 1620. In comparing the two styles we see many similarities but also a difference. Orente is working in a style called baroque classicism. This style seeks to evoke more a sense of the classical heritage of Western culture and, inspired by Raphael the artist of 100 years before, often look as thought they are staged scenes from a Shakespeare play set in ancient Rome. Stylistically, there is always more colour and the edges are sharper and cleaner - sometimes this can tend to give them a more sterile and less lively feel. In contrast the baroque naturalist style use monochrome and broad focus much more and has a more vigorous, spontaneous feel. My preference is for baroque naturalism. To the modern eye, although once pointed out we can distinguish between the two streams, they still look similar. At the time though, each school thought of itself as very different from the other. Each saw theirs as the more authentic form of sacred art and and would be openly rude and dismissive about the other.

Paintings: Anthony Van Dyck is the small inset above, and right at the bottom. Pedro Orrente is immediately below this text.

The baroque naturalism of Van Dyck and the baroque classicism of Orente compared. We are now in Holy Week. To help our contemplation, here are two different paintings of the Palm Sunday scene - Christ's Entry into Jerusalem. Both are by 17th century painters from the heyday of the baroque period. The first is by Sir Anthony van Dyck, who was taught by Rubens and works in the baroque naturalism style (other painters in this form would be, for example, Velazquez or Zurbaran). The second is by lesser know Spanish artist who was trained by El Greco called Pedro Orrente. He painted this is 1620. In comparing the two styles we see many similarities but also a difference. Orente is working in a style called baroque classicism. This style seeks to evoke more a sense of the classical heritage of Western culture and, inspired by Raphael the artist of 100 years before, often look as thought they are staged scenes from a Shakespeare play set in ancient Rome. Stylistically, there is always more colour and the edges are sharper and cleaner - sometimes this can tend to give them a more sterile and less lively feel. In contrast the baroque naturalist style use monochrome and broad focus much more and has a more vigorous, spontaneous feel. My preference is for baroque naturalism. To the modern eye, although once pointed out we can distinguish between the two streams, they still look similar. At the time though, each school thought of itself as very different from the other. Each saw theirs as the more authentic form of sacred art and and would be openly rude and dismissive about the other.

Paintings: Anthony Van Dyck is the small inset above, and right at the bottom. Pedro Orrente is immediately below this text.