Here is a review of a selection of Frank La Rocca’s compositions called In This Place, written by Br Brad T. Elliot OP; it appeared first, in slightly altered form, on page 49 of the Fall 2015 edition of Sacred Music, the journal of the CMAA.

I have only just seen this, but I thought to bring it to your attention for a couple of reasons, the first being that I think that Frank La Rocca’s work deserves to get more attention.

The second reason is that the principles by which the reviewer judges the merit of La Rocca’s works are themselves worthy of study. Br Brad Elliot, who is a Dominican of the Western Province of the United States, has a good grasp of music theory (way beyond my own) and of the principles of sacred music. He brings his knowledge of both into the discussion. As such, in this short piece, I feel he outlines succinctly a guide for patrons, composers, and for the judgment of such compositions, in accord with general principles are applicable in all the creative arts.

Br Brad explains very well why it is imperative that we always have new compositions to breathe life into any artistic tradition. No tradition can rely on a canon of past works alone; without continuing creativity, it will cease to engage new people and become dead. As he puts it:

Simply put, the giving over or tradere of the past into the future must pass through the present as a necessary middle term; the present is where the real tradition takes place.

He stresses also the importance of exploring modern forms of music, as he says:

...modern harmony should not be feared as a threat to sacred beauty.

But he is quick to point out that such exploration can never be used as a reason for compromising the essential principles of sacred music.

Is Frank La Rocca’s music doing this? Perhaps. I think so, and Br Brad thinks so. But we must be clear that fulfillment of the criteria that Br Brad lays down is not the only requirement. In the end, it has to appeal at a natural level to many people as well. This is the great challenge to the artist in any field, and the mark of true creativity. Neither Br Brad nor myself are the final arbiters of taste and so the final test of its goodness is not if he or I like it, but its popularity. If it is good, it will be performed, and congregations will be drawn to it. And only time can tell us this in regard to Frank La Rocca’s or any other composer’s music. You can decide for your self by listening to his work. Here is his O Magnum Mysterium.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3SMLinOVi7c

We ought to encourage the continued creativity of people who understand the principles of sacred music and modern music, and are prepared to take that great risk in looking for ways of combining the two. Frank La Rocca looks to the incorporation of modern classical forms. This is not the only area of modern music in which people can look for inspiration, but whatever approach is taken, it has to be done with the dedication and respect for tradition with which we see from Frank and a few others. (Another example is my colleague on this blog, Peter Kwasniewski). The more people who are doing so, the more likely it is that the sacred musical form of today will break out of the esoteric circle of those who are deeply interested in such things and emerge as a new, popular and noble form. The music that does this will characterize our age when future generations look back at the early 21st century.

Someone once tried to persuade me that I should appreciate the highly dissonant classical music of the 20th century with the absurd opening argument that “modern music isn’t as bad as it sounds.” While there is always a place for guiding people into an appreciation of what is good, if we have to persuade people that they ought to like something, we have failed.

Thoughtful criticism that highlights what is good is as necessary to the process of cultural transformation as the work of the creative artist. I think both Br Brad Elliot and Frank La Rocca are showing us the path by which we can succeed (not forgetting Sacred Music which prints the review of course!)

The Fall edition of Sacred Music has just appeared online, so you can read the review in the journal, here. Alternatively, I reproduce it here with permission:

Composers of sacred music are in a precarious position in today’s world; in many ways, they are a dying breed. On the one hand, they find themselves competing with an aesthetic of the past, as so many in their audience are driven by a nostalgia for a form and harmony indicative of music centuries-old. On the other hand, they are immersed in a post-modern world that has all but forgotten the very natural laws of beauty, the very symmetry, proportion, and order imbued in creation that any authentic imitation of that creation – the ancient notion of art – should reflect. The contemporary composer of sacred music seems to be straddling two incommensurable worlds. How is he to be faithful to the tradition by assimilating its rich vocabulary, and yet express this vocabulary and pass it on to a post-modern world that has all but revolted against that language?

The tension between purist and progressive is deeply felt by the sacred music composer. The Christian audience in today’s world inevitably defaults to equating a sacred aesthetic with an ancient or an old aesthetic, and this antiquity tends to become more and more idealized as it fades into a past known only through the frozen images of paintings or the archaic prose of worn books. Yet if the tradition of sacred music is to be handed on at all, if it is to be a true tradition –tradere – or giving over of something, it cannot remain in the idealized past. After all, sacred music is not a mere platonic universal floating in a world of ideas; it must be instantiated in a present particular work, that is, a piece of music that contains all the individuality and unrepeatable character of any other. If the tradition of sacred music is to be known, it must be incarnated in the here-and-now, given flesh and matter through some distinct composition. Simply put, the giving over or tradere of the past into the future must pass through the present as a necessary middle term; the present is where the real tradition takes place.

But here is precisely the dilemma; if any particular composition is to be a true giving over of something and not a mere replica of the past, than this work will naturally embody the character of the present time. The harmony, feel, texture, and aesthetic of the contemporary world will serve as the matter out of which the tradition again takes flesh. But can contemporary music actually provide a sufficient matter for a true expression of the sacred? Has the twentieth century, and now the twenty-first, provided a musical language with which the tradition can again be spoken? Or would not modern harmony, with its dissonance and atonality, compromise the sacred to an unrecognizable degree? Unfortunately, many answer this last question with a simple “yes.” This is the nature of the tension that composers know all too well.

For the past twenty years I have been a lover of sacred music, both its history and contemporary trends, and I have grown accustomed to this tension. I confess that, for much of my life I would have, like the many mentioned above, simply denied that the modern aesthetic could ever express the transcendence which is the hallmark of sacred music. As easy as it may be to succumb to this doubt given the pervasive banality of so much contemporary music, every so often a composer emerges who provides the needed exception to this presumed distrust, a composer who fully embraces contemporary forms of structure and harmony and yet still remains rooted in the sacred tradition. The composer Frank La Rocca has again provided this welcomed exception and the album In This Place is proof that an artist fully immersed in twentieth-century music can again speak the language of the sacred musical tradition to contemporary ears in a way that is understandable and attractive.

The album In This Place is unquestionably a work born from Catholic Christian spirituality with six of the eight compositions as settings of biblical or liturgical texts. From the opening, O Magnum Mysterium, a setting of the responsorial chant of Matins of Christmas, to the closing Credo, a setting of the Latin text of the Nicene Creed, the album is an explicit expression, in music, of the faith of the historic Christian Church. There is Expectavi Dominum with text from Psalm 40, Miserere with text of King David’s great prayer of repentance in Psalm 51, the Pentecost Sequence Veni Sancte Spiritus, and the famous prayer of St. Thomas Aquinas, O Sacrum Convivium. In addition to these vocal works, there is a piano work entitled Meditation, and an instrumental chamber work, In This Place, from which the album gets its name.

The entire album is a kaleidoscope of colors, textures, and moods where, like the psalms and liturgical prayers themselves, the full spectrum of human emotion is embraced and felt. La Rocca is undoubtedly adept at composing with the dissonance and set-harmony of twentieth-century music fully playing with all its qualities, and yet the album touches tonal harmony at every turn. As one listens from start to finish, the composer takes the listener on a journey through both the traditional narrative-like tension/release of tonal harmony and the persistent chromatics of the modern era. In a sense, La Rocca pulls the best from both worlds and weaves them together into his own distinctive voice. While the influence of Renaissance composers like Orlande de Lassus and William Byrd may be heard, particularly in the choral works, the influence of twentieth-century composers is evident. One can hear the harmonic sharpness and rhythmic agility of Stravinsky as well as the mystical naturalism of Mahler. Far from being a patch-like jumble of the old and the new, it is an authentic blending in the truest sense of the word. Any lover of twentieth-century music will find in La Rocca a composer who fully understands his taste. Nonetheless, through these works, the lover of traditional sacred music will also hear, echoing as from the past into the present, a true icon of holy transcendence once again instantiated in the present.

The blending of old and new elements is best seen in La Rocca’s use of old church modes. Traditional modal harmony is present in much of the album yet the composer never compromises its contemporary feel. For example, Veni Sancte Spiritus, for soprano voice and chamber ensemble, is composed in the Aeolian mode. The piece remains rooted in the church mode from beginning to end and yet, by exploring the range of intervals imbedded therein, La Rocca is able to extract gradations of dissonance and consonance that one would not expect. In modern fashion, the composition is held together by an angular motif, a succession of open ascending intervals that is heard from both voice and instrument. While a calm melancholic feel pervades, there is also expressed a subtle note of hope and expectancy so appropriate for the text of the Veni Sancte Spiritus which begins, “Come, Holy Spirit, and from your celestial home radiate divine light.”

Similarly, the title track of the album, In This Place is also composed in the Aeolian mode. The composition, a solely instrumental work, is passionately mournful with an interplay between reed and string that is eerily prayer-like. La Rocca creates this mood, not only through harmonic dissonance, but also through taking advantage of the biting tambour of string and reed. There is a deep introspective element to the work reminiscent of the art songs of Mahler.

The Credo is, as one might expect, most reflective of traditional forms. The influence of Gregorian chant can be heard in the opening phrase yet the music quickly expands to the use of counterpoint indicative of Renaissance polyphony. It is an experiment in the balance and contrast that may be achieved when music suitable for liturgy is combined with more modern concert forms. The settings of the psalms, Expectavi Dominum and Miserere, likewise harken back to an earlier polyphonic style but utilize modern harmonic colors to punctuate the biblical text. For example, Expectavi Dominum, the text of Psalm 40 which begins “I waited patiently for the Lord,” highlights the ache of this waiting by opening with the unconventional dissonance of a minor second. Miserere is, like the text of Psalm 51 itself, a musical journey from the bitterness of contrition, through the pain of repentance, and finally to the tranquility that accompanies faith in the Lord’s mercy. The music first expresses, through minor modes and dissonance, the sadness and gravity of King David’s confrontation with the horror of his own sin. But then as the text “cor mundum crea in me, Deus” is sung (create in me a clean heart O God), the music transforms into a joyful, restful praise of God. Following the biblical text, the music begins with mourning and anguish but ends in a musical Sabbath-rest.

A particularly noteworthy piece is the sixth track on the album, O Sacrum Convivium. This is a setting of the prayer composed by St. Thomas Aquinas in praise of the Holy Eucharist and, like the rest of the album, it is a hauntingly beautiful blend of classic and contemporary elements. The work most reveals the influence that English Renaissance polyphony, particularly that of William Byrd, has had on La Rocca’s choral style. Of all the compositions, it contains the most triadic harmony and best represents traditional polyphonic structure. A classical yet unexpected opening occurs when the bass, tenor, alto, and soprano each respectively state the opening melody in ascending sequence. However, these ascending statements are not removed by a perfect fifth as one would traditionally expect, rather, they are each removed by a perfect fourth giving the opening a suspended and otherworldly feel most fitting for the text of the prayer. The polyphonic chant is interrupted by a recurring motif, arresting of the attention with its dense chromatic clusters, that emphasizes the theologically rich texts “in quo Christus sumitur” (in which Christ is received) and “mens impletur gratia” (the mind is filled with grace).

The album as a whole is a courageous blend of styles and genres that is atypical for the fractioned world of modern music. Thus, it bears a confidence that is only born of years of artistic maturity. The sheer variety of the album pays testament to the diversity of influences that have shaped the composer’s ear and, what is more, pays greater testament to a composer who has himself wrestled with the interplay between these influences and has emerged from the battle. All lovers of sacred music wearied by the divide between the traditional and modern aesthetic will find happy repose in the album In This Place. Its varied collection hints that La Rocca has gone before us through this divide and is now giving to others the fruits of his own musical and spiritual journey.

Indeed, modern harmony should not be feared as a threat to sacred beauty. In This Place is proof of this. For sacred beauty, like God Himself, is timeless; no age can claim Him as its own. Beauty, wherever it is found, may be used as an icon of God’s holy presence, and the composer Frank La Rocca has again given the world a fresh example of this truth. The album In This Place, far from being a mere restatement of the old, is a new instantiation of the tradition of sacred music in our own time. Far from re-creating the past, La Rocca speaks the tradition with his own musical voice. I encourage all lovers of music to invest time in listening to his work. It is time well spent.

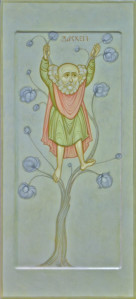

These seven liberal arts and the artists who most exemplify them are featured on the Royal Portal of Chartres Cathedral. (Geometry: Euclid, Rhetoric: Cicero, Dialectic: Aristotle, Arithmetic: Boethius, Astronomy: Ptolemy, Grammar: either Donatus or Priscian)

These seven liberal arts and the artists who most exemplify them are featured on the Royal Portal of Chartres Cathedral. (Geometry: Euclid, Rhetoric: Cicero, Dialectic: Aristotle, Arithmetic: Boethius, Astronomy: Ptolemy, Grammar: either Donatus or Priscian)

Andrew Thornton-Norris offers readers his new poem, Moments of Vision, along with an explanation of its composition. An Englishman based in the west of England, whose work is admired and published on both sides of the Atlantic, Andrew teaches literature and poetry at Pontifex.University.

Andrew Thornton-Norris offers readers his new poem, Moments of Vision, along with an explanation of its composition. An Englishman based in the west of England, whose work is admired and published on both sides of the Atlantic, Andrew teaches literature and poetry at Pontifex.University.

How what started as a budding artist’s quest for a formation in beauty and creativity became a manifesto for cultural renewal; and will now be available as a whole program of courses offered by

How what started as a budding artist’s quest for a formation in beauty and creativity became a manifesto for cultural renewal; and will now be available as a whole program of courses offered by  The problem was how to get the necessary training. I knew that no existing art school would give me what I was looking for. I needed the traditional skills and although it was difficult to find people who still taught drawing and painting with rigor, it was just about possible. The real problem was knowing how to direct those skills once I had them.

The problem was how to get the necessary training. I knew that no existing art school would give me what I was looking for. I needed the traditional skills and although it was difficult to find people who still taught drawing and painting with rigor, it was just about possible. The real problem was knowing how to direct those skills once I had them.