The Christian connection between culture, conservative values, the common good and the natural law

The Raising of Lazarus

See How They Love One Another

Painting Workshop, Rome, August 6-17: The Methods of Caravaggio and Titian.

This summer Pontifex University is proud to sponsor a unique workshop taking place in Italy. "The Art and Theology of the Catholic Reformation in Rome", which will take place this August 6 - 17 at the Accademia Urbana delle Arti in the center of Rome. This intensive two-week/60- hour course will provide a comprehensive overview of the painting methods of artists of the Catholic Reformation and the theology that underpinned their works.

The Importance of Seeing Paintings in Context

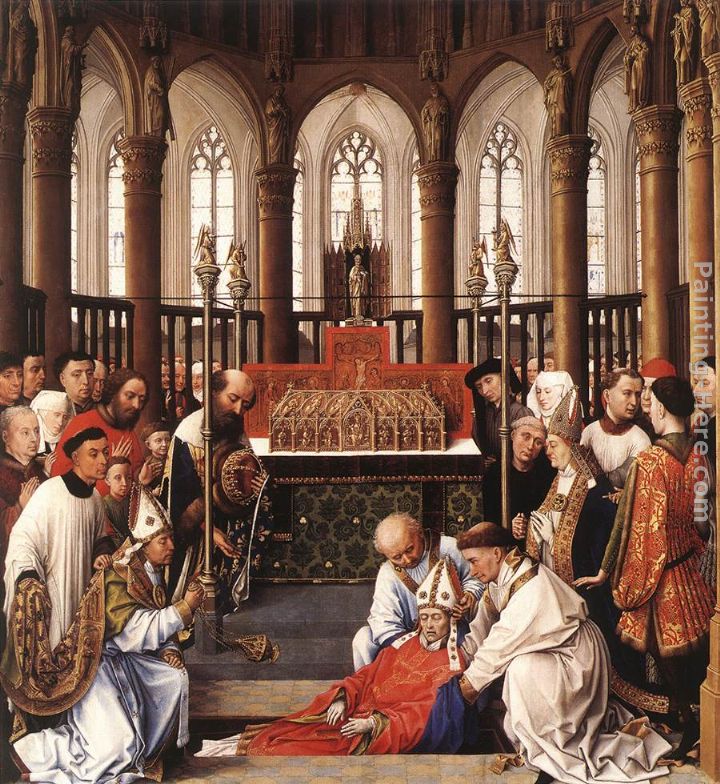

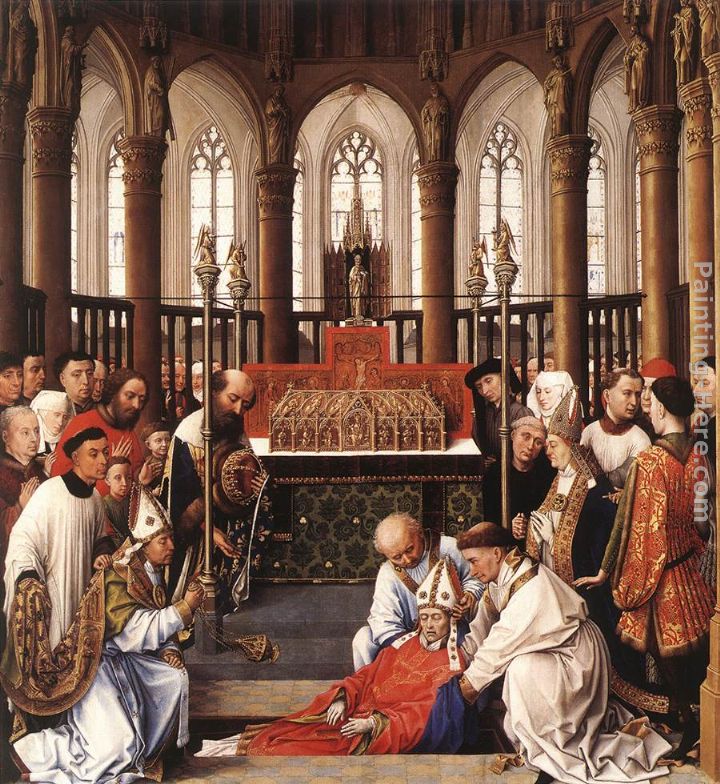

I would like to draw readers' attention to a piece in The Catholic Herald written by Fr Anthony Symondson. He has reviewed the exhibition Devotion by Design which is at the National Gallery in London and which runs until October 2nd. The exhibition is unusual in that, commendably, altarpieces are displayed along with simulated altars so that visitors can get a feel for the setting in which they ought be placed. One of the pieces on display is Rogier van der Weyden's Exhumation of St Hubert, shown left.

While the only way to get a full sense of the importance of context for such a piece is to see it in church while praying the liturgy, what the museum has done does at least indicate the intended purpose of the piece. It also makes the point that context of a painting is important and open our imaginations to what it might have been like originally. I am pleased to see a gallery thinking about this.

I would like to draw readers' attention to a piece in The Catholic Herald written by Fr Anthony Symondson. He has reviewed the exhibition Devotion by Design which is at the National Gallery in London and which runs until October 2nd. The exhibition is unusual in that, commendably, altarpieces are displayed along with simulated altars so that visitors can get a feel for the setting in which they ought be placed. One of the pieces on display is Rogier van der Weyden's Exhumation of St Hubert, shown left.

While the only way to get a full sense of the importance of context for such a piece is to see it in church while praying the liturgy, what the museum has done does at least indicate the intended purpose of the piece. It also makes the point that context of a painting is important and open our imaginations to what it might have been like originally. I am pleased to see a gallery thinking about this.

Good sacred art is painted so that it engages the person at precise moments in the liturgy and then directs their attention beyond the work of art to something greater – by for example making sure in the case of the reredos that there is sufficient contrast so that the host is visible when held aloft. This is something that artist should always be aware of. Even within a painting, one part in isolation looks different when viewed in relation to all the other parts. Artists are taught to consider the unified view. Once the form of a painting has been established – the basic shapes, tones and colours – then the so much of the final part of the process is subtle alteration using colour washes, glazes and scumbles so that each part speaks to the others in such way that the piece has unity.

Similarly, the artist must try to consider the wider context into which it is to be placed. Works look different when placed on dark or light backgrounds, or when there are other paintings around. Also and most importantly, the position relative to the liturgy must be considered.

Similarly, the artist must try to consider the wider context into which it is to be placed. Works look different when placed on dark or light backgrounds, or when there are other paintings around. Also and most importantly, the position relative to the liturgy must be considered.

Consider Caravaggio’s Calling of St Matthew. This is a great painting even when viewed in isolation, but the ideal position for this, I suggest, is in a side chapel on the left hand ie north side of the church, on an east wall so that at the point of elevation someone in the main body of the church could see both the painting, in the left hand side of their vision, and the elevated host. This would give the appearance that the source of light was the Blessed Sacrament itself - the Light calling St Matthew - thus reinforcing visually the fact that Christ is really present within it.

One of the wonders of nature for me is how each object can be beautiful and complete in itself, can also be a beautiful part of a wider landscape and, furthermore, contains within it beautiful parts in perfect relation to each other. We need only think of a rose: each petal within it is beautiful and placed so that together they form the flower; and then each bloom is placed in relation to the others, to the stems and leaves so that we have a beautiful rosebush.

When I take commissions I do my best to have this model in mind and consider carefully not just what the form of the painting itself, also where it will be placed and how it can be most beautiful in its final setting.

Caravaggio and His Followers - An Exhibition in Ottowa

Thanks go to a reader who told me about an exhibition of the works of Caravaggio and his followers taking place at the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa. It's too far away from where I live me to get to it, but it seemed such an interesting theme that I felt compelled to write about it anyway! It acknowledges the influence that this great artist had on the art of the Catholic Counter Reformation. Also, the lists of artists featured gives many familiar names but some not so familiar (ie some I hadn't heard of!) whose work is high quality and this represented a fruitful new seam of interest to me to mine.

Working at the period around the beginning of the 17th century, Caravaggio is often credited as the artist whose work marks the beginning of the baroque period. He developed the visual language of light and dark that characterizes the baroque period by imbuing with a spiritual significance. He also became the figurehead of the more naturalistic stream of artists of the 17th century baroque, who emphasised very strongly painting what is seen directly onto the canvas. He stood against a group that saw themselves as drawing on classical themes more strongly, with Annibale Caracci as their talisman. Caracci and the classisists, who would later include figures such as Poussin, looked to the work of Raphael and had a more widely coloured and polished feel in their work. Compositionally the work of the more naturalistic group used often depicted figures in contemporary clothes, whereas the classicist stream (and here I characterise the extremes) tended to paint everything as though it was a scene out of ancient Rome. Their methods differed slightly too. Although both emphasised observation from nature very strongly, Caravaggio would paint directly onto the canvas from models, while Carracci would happily base his compositions on drawings and studies of models.

Thanks go to a reader who told me about an exhibition of the works of Caravaggio and his followers taking place at the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa. It's too far away from where I live me to get to it, but it seemed such an interesting theme that I felt compelled to write about it anyway! It acknowledges the influence that this great artist had on the art of the Catholic Counter Reformation. Also, the lists of artists featured gives many familiar names but some not so familiar (ie some I hadn't heard of!) whose work is high quality and this represented a fruitful new seam of interest to me to mine.

Working at the period around the beginning of the 17th century, Caravaggio is often credited as the artist whose work marks the beginning of the baroque period. He developed the visual language of light and dark that characterizes the baroque period by imbuing with a spiritual significance. He also became the figurehead of the more naturalistic stream of artists of the 17th century baroque, who emphasised very strongly painting what is seen directly onto the canvas. He stood against a group that saw themselves as drawing on classical themes more strongly, with Annibale Caracci as their talisman. Caracci and the classisists, who would later include figures such as Poussin, looked to the work of Raphael and had a more widely coloured and polished feel in their work. Compositionally the work of the more naturalistic group used often depicted figures in contemporary clothes, whereas the classicist stream (and here I characterise the extremes) tended to paint everything as though it was a scene out of ancient Rome. Their methods differed slightly too. Although both emphasised observation from nature very strongly, Caravaggio would paint directly onto the canvas from models, while Carracci would happily base his compositions on drawings and studies of models.

What is interesting is how many artists are listed as being ‘followers’ of Caravaggio. Many would be considered artists in their own right – Ribera, George de la Tour. These would not normally be considered followers in the sense of being in a Caravaggio school, but given that a crucial part of the training of all artists was the copying of masters, I’m guessing that at the very least, they will have copied Caravaggio’s work at some stage at the very least, and this is the reason for their inclusion. The National Gallery acknowledges this broader focus, saying that works are ‘by painters who had direct knowledge of his work, as well as those who were active in Rome during his lifetime and in the first few decades after his death.’ I think that it is all the more interesting for this.

What is interesting is how many artists are listed as being ‘followers’ of Caravaggio. Many would be considered artists in their own right – Ribera, George de la Tour. These would not normally be considered followers in the sense of being in a Caravaggio school, but given that a crucial part of the training of all artists was the copying of masters, I’m guessing that at the very least, they will have copied Caravaggio’s work at some stage at the very least, and this is the reason for their inclusion. The National Gallery acknowledges this broader focus, saying that works are ‘by painters who had direct knowledge of his work, as well as those who were active in Rome during his lifetime and in the first few decades after his death.’ I think that it is all the more interesting for this.

Rubens is another example of one of these artists who would not be classified as a follower of Caravaggio in the usual sense of the word, but is worthy of consideration here. We know from his writings that he was very careful about which Masters he copied as he felt it would influence strongly the taste of the artist. For example, he implored artists not just draw casts for practice, but to consider carefully which casts they drew and only pick the most beautiful because this would influence the work they produced, which is never solely a reproduction of what is seen.

The commentary of this exhibition tells us that even Caravaggio modified what he saw to some degree: ‘He painted directly from live models posed before him in the studio, studying how the light fell over them, and observing the different textures and surfaces. He then transformed what he saw before him with his own distinct artistic vision. As one of his patrons once said his works were “painted partly from observation of reality, partly from his imagination.”’

The imagination is molded by the art we copy, hence Rubens’s concern.

The artists whose works are shown in the exhibition include many that are not household names, and not all sacred art. However, the style is all derived from that which developed as part of the sacred art and speaks of the power of Catholic culture at the time. The images shown here are works of sacred art by some of the lesser names of the exhibition. They are paintings that caught my eye as I was doing my own research and are not necessarily in the exhibition itself.

Above, right: Simon Vouet, the Fortune Teller

Triphome Bigot, St Sebastien

Nicolas Regnier, St Matthew

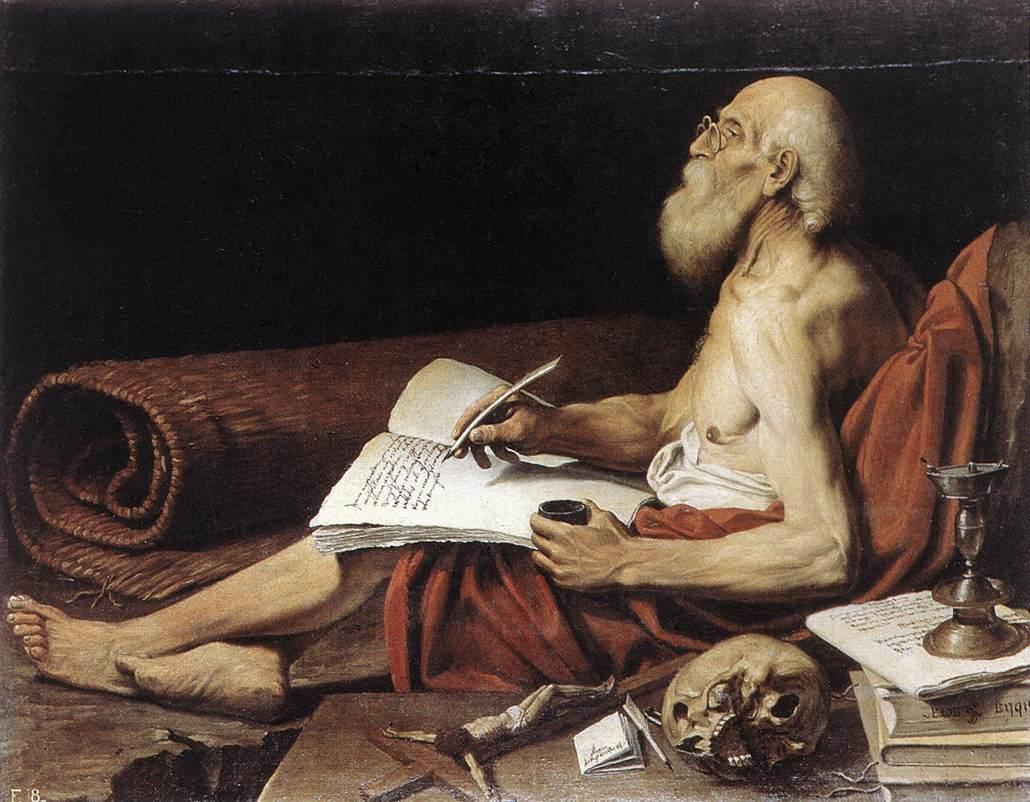

Lionel Spinada, St Jerome

Gerrit van Honthorst, St Joseph in his Workshop