Following on from last week’s article Heart to Heart, about the commissioning of the Sacred Heart paintings, there were two points that I raised for discussion. The first is the suitability of the iconographic form for a Sacred Heart painting. A number of people who spoke to objected to this (some quite forcibly!). If I have understood their points properly, then it seemed to be based upon the idea that the iconographic form is necessarily an Eastern (and one person even said an Orthodox form) so the portrayal of a Western devotion is not appropriate. The first point to make is that the Sacred Heart, although originating in the West, is no longer restricted to it. I was told by a Melkite priest that the Sacred Heart is a popular devotion in the Eastern Church too. Second, this view of icons as being an exclusively Eastern form is contrary to the Catholic view. I have written before, here and here that what characterizes the iconographic form is that it is a style that is consistent with an image of eschatological man – mankind, redeemed, in heaven, so to speak. There are variants of the iconographic form that emanate from the Eastern Church and the Western Church (for example Carolingian, Ottonian or Romanesque art). Therefore, if it is right to represent Christ in the iconographic form at all (and of course it is) then it is right, I would argue, to paint images of the Sacred Heart in that form too. (The same could be said in regard to the other liturgical forms – just as it is appropriate to paint Christ in the gothic and baroque styles, it is appropriate also to paint images of the Sacred Heart in those forms.)

Following on from last week’s article Heart to Heart, about the commissioning of the Sacred Heart paintings, there were two points that I raised for discussion. The first is the suitability of the iconographic form for a Sacred Heart painting. A number of people who spoke to objected to this (some quite forcibly!). If I have understood their points properly, then it seemed to be based upon the idea that the iconographic form is necessarily an Eastern (and one person even said an Orthodox form) so the portrayal of a Western devotion is not appropriate. The first point to make is that the Sacred Heart, although originating in the West, is no longer restricted to it. I was told by a Melkite priest that the Sacred Heart is a popular devotion in the Eastern Church too. Second, this view of icons as being an exclusively Eastern form is contrary to the Catholic view. I have written before, here and here that what characterizes the iconographic form is that it is a style that is consistent with an image of eschatological man – mankind, redeemed, in heaven, so to speak. There are variants of the iconographic form that emanate from the Eastern Church and the Western Church (for example Carolingian, Ottonian or Romanesque art). Therefore, if it is right to represent Christ in the iconographic form at all (and of course it is) then it is right, I would argue, to paint images of the Sacred Heart in that form too. (The same could be said in regard to the other liturgical forms – just as it is appropriate to paint Christ in the gothic and baroque styles, it is appropriate also to paint images of the Sacred Heart in those forms.)

Similarly, the iconographic style is not communicating a message restricted to any particular time in history. It is communicating the timeless realm of heaven. So the time in history when the devotion arose is irrelevant to the discussion. (Although, in fact, the Sacred Heart devotion might even have begun, according to my research as early as the 11th century, which would place it in the period when the standard art form in the West was Romanesque, which was iconographic anyway, also, though not specifically linked to the Sacred Heart devotion, there are a few older images of Christ's heart as a symbol of love. I found one going back to 450AD).

Similarly, the iconographic style is not communicating a message restricted to any particular time in history. It is communicating the timeless realm of heaven. So the time in history when the devotion arose is irrelevant to the discussion. (Although, in fact, the Sacred Heart devotion might even have begun, according to my research as early as the 11th century, which would place it in the period when the standard art form in the West was Romanesque, which was iconographic anyway, also, though not specifically linked to the Sacred Heart devotion, there are a few older images of Christ's heart as a symbol of love. I found one going back to 450AD).

The other point relates to how we show the light emanating from the heart. The concern of someone, whom I respect as being very knowledgeable on the tradition, that a halo was not appropriate for the heart, although this is a representation of uncreated light, within the tradition the nimbus of light, the halo, has only been applied to the head. Therefore, rays (as one might see in a monstrance) were better. This is a strong argument and worth of further consideration. While we should never say that just because it hasn't been done before we can't now, we must be respectful of tradition and try to consider why it hasn't. On reflection, however, I feel that it is appropriate to use a halo if the artist chooses, but I am still open to persuasion and would love to see any thoughts that readers have on the matter.

![]() Here are the points I would make in response: it is certainly the case that the halo has a strong symbolic meaning beyond simply the pictorial representation of uncreated light. It is telling us something about the person – that this is a saint or the glorified person. When we see a person their head is the place most appropriate visible part that represents the person – we naturally tend to look at the face as of a person as a ‘window to the soul’; and most would not consider for a moment, for example, putting a halo around the hand to say something about the person. However, tradition does say that the heart, perhaps even more than the head, symbolizes a person. The heart is the human centre of gravity, our very core that incorporates body and soul. It is the place that represents the whole person, the vector sum of all our actions and thoughts. This is why the heart represents love. We are made for love and so the place that represents the person is also the symbol of what the person is made for. This is even more the case for the person of Christ, who is not made for love but rather, as God He is Love.

Here are the points I would make in response: it is certainly the case that the halo has a strong symbolic meaning beyond simply the pictorial representation of uncreated light. It is telling us something about the person – that this is a saint or the glorified person. When we see a person their head is the place most appropriate visible part that represents the person – we naturally tend to look at the face as of a person as a ‘window to the soul’; and most would not consider for a moment, for example, putting a halo around the hand to say something about the person. However, tradition does say that the heart, perhaps even more than the head, symbolizes a person. The heart is the human centre of gravity, our very core that incorporates body and soul. It is the place that represents the whole person, the vector sum of all our actions and thoughts. This is why the heart represents love. We are made for love and so the place that represents the person is also the symbol of what the person is made for. This is even more the case for the person of Christ, who is not made for love but rather, as God He is Love.

Normally the heart is not visible, so the question as to whether or the artist should apply a halo to it does not come up. However, in this case it is, and I would argue therefore that it is not inappropriate, at least, to put the halo around the heart.

Another point that was raised is that it seems to disembody the heart. It is a matter of opinion as to whether this is a problem, I think. My response to this is that the heart has been no more disembodied by putting a halo around it than it has by placing rays around it. The Maryvale image, which is based upon the visions of St Gertrude in the 13th century, has Christ presenting his heart to us in the palm of his hand, this is quite a disembodying action, it seems to me!

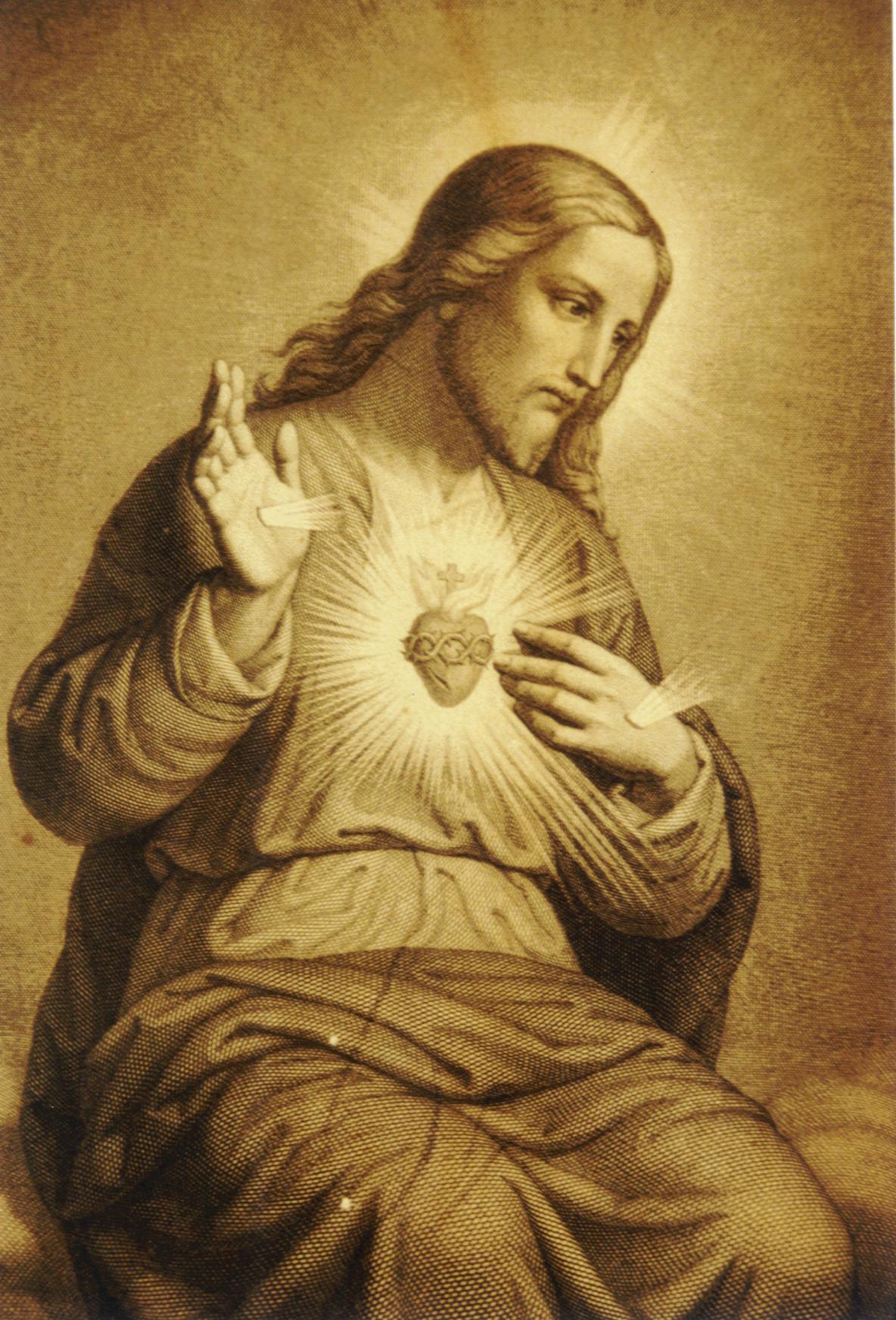

The discussion so far has been concerned with general principles. It does not account for individual taste or the quality of the images portrayed. Even if consistent with the principles that constitute a particular tradition, a painting can still be poorly executed. And I have to say that most of the Sacred Heart images I see are, to my eye, sentimental and unattractive. (There are exceptions. I have included some that appeal to me, including once again the 18th century stain-glass window in the Maryvale Institute in Birmingham.)

Images inserted into text, from top: from St Patrick's El Paso, Texas; the Maryvale stain-glass window; a modern icon of the Sacred Heart.

And images below: an 18th century engraving; a 15th century woodcut of the Five Wounds of Christ; a heart and cross from 450AD.