Engaging the Whole Person in Prayer Opens us up Further to Inspiration and Creativity - The Divine Office III, part II here, part I here.

Engaging the Whole Person in Prayer Opens us up Further to Inspiration and Creativity - The Divine Office III, part II here, part I here.

‘In the sight of angels I will sing praise to you (Ps 138:1). Let us rise in chanting that our hearts and voices harmonise.’ (Rule of St Benedict: Ch 19)

The heart is the human centre of gravity, our very core that incorporates both body and soul. It is the place that represents the whole person, the vector sum of all our actions and thoughts. If our hearts are to be in harmony with the prayers of the angels in heaven as St Benedict suggested, we need to consider not just our thoughts and voices, but our actions, our bodies and even how are senses are engaged in the action of prayer. The heart is also the place that is closest to God (considering both physical and spiritual human anatomy). It is closest in the sense of being that place that is most directly in contact with Him. So, if we seek the ideal stated, and harmonise our hearts with the prayer of the heavenly hosts, we will also be more sensitive to inspiration because the whole person is engaged. The Liturgy of the Hours is the means to continuous prayer, as discussed last week.  If in the context of the Liturgy our continuous prayer simultaneously engages the whole person then can we are opening ourselves up to the greatest degree possible to God’s grace. To the degree that we cooperate with grace this will help us make all our life decisions and help us to move towards the fulfillment of our personal vocation in life. This will be perfectly ordered also to the model of charity, that is, love of God. To the degree that we match these standards there will be perfect harmony with the objective standard of God’s will. This is the supernatural path to inner peace, peace with our neighbour and a life in harmony with creation.

If in the context of the Liturgy our continuous prayer simultaneously engages the whole person then can we are opening ourselves up to the greatest degree possible to God’s grace. To the degree that we cooperate with grace this will help us make all our life decisions and help us to move towards the fulfillment of our personal vocation in life. This will be perfectly ordered also to the model of charity, that is, love of God. To the degree that we match these standards there will be perfect harmony with the objective standard of God’s will. This is the supernatural path to inner peace, peace with our neighbour and a life in harmony with creation.

As I have said before, I don't claim to be an expert in these matters at all, but I can pass on the guidance that I was given when I asked about these things. Here are the things that were suggested to me a way of involving the whole person in prayer. I seek, as well as seeking to attune my thoughts to the prayer of the Liturgy, to engage all my senses and my physical being in the prayer too:

Chant: the use of voice (and hearing). Even if I do it on my own, I will sing the Office (quietly!). As an aside: ironically singing on my own regularly stopped me from being self conscious about singing in front of others. I was so used to hearing my own voice and not being unsettled by it, that in time the thought of others hearing it too didn’t worry me.

Chant: the use of voice (and hearing). Even if I do it on my own, I will sing the Office (quietly!). As an aside: ironically singing on my own regularly stopped me from being self conscious about singing in front of others. I was so used to hearing my own voice and not being unsettled by it, that in time the thought of others hearing it too didn’t worry me.

Posture: consider our posture at all times. In the Mass I try to follow the rubrics, and in the Liturgy of the Hours do my best to follow the traditional postures such as bowing, standing, sitting. Why is posture important? I see it like this: in the ideal every aspect of human nature is directed towards God, my actions and motives. At any time my motives for doing something are likely to be mixed and not perfectly pure. I have found that even if I don’t feel like praying or feel very peaceful, I can resolve to do it anyway and adopt a reverential posture. My body will tend to lead my heart in the right direction. And where my heart goes, my thoughts and feelings will follow suit. The following scheme was suggested to me and we try to follow this when we say the Office together at Thomas More College of Liberal Arts: we stand through opening words and hymn until the psalms are recited, when we sit, and we stand again for the gospel canticle until the close or if there is no gospel canticle we stand for the closing prayer ; we bow (and if sitting, say at the end of the psalm, we stand again) in honour of the Trinity for the last verse of each hymn and the glory be; we bow our heads at mention of the name Jesus.

Engaging our sense of sight: pray with visual imagery and use candles. I light candles to mark the time of prayer (it reminds me that Christ is the Light of the World) . If I pray to as named saint, for example, Our Lady, I turn and look at an image of her as I do so. At home I create and icon or image corner as a focus for prayer. This can be as simple as have a single icon, or become of more sophisticated combination of images changing according to season and day (see earlier article Praying with Visual Imagery). The ideal core imagery for and icon corner, in accordance with tradition, is to have a crucifixion in the centre, which portrays the suffering Christ; an image of Our Lady on the left; and an additional image of Our Lord glorified on the right. (See past article, How to Make an Icon Corner]

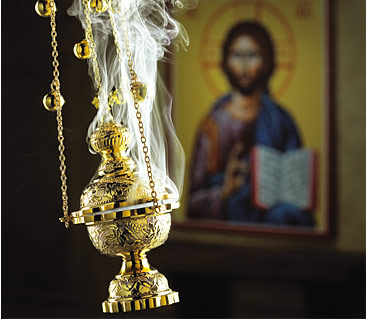

Incorporating the sense of smell –I was encouraged to use incense, for example when singing the gospel canticles. However, I was told, it should be used selectively in accordance with the hierarchy of the liturgy so everything together points to the Sunday Mass as it highpoint. So for example, in community incense can be used on Feast days and Solemnities at Vespers, Lauds and Compline (when gospel canticles are sung), but only if incense is also used at Sunday Mass.

Incorporating the sense of smell –I was encouraged to use incense, for example when singing the gospel canticles. However, I was told, it should be used selectively in accordance with the hierarchy of the liturgy so everything together points to the Sunday Mass as it highpoint. So for example, in community incense can be used on Feast days and Solemnities at Vespers, Lauds and Compline (when gospel canticles are sung), but only if incense is also used at Sunday Mass.

v) Incorporating taste and touch-the Eucharist. We do not take communion during the Liturgy of the Hours, but we should not forget the wider picture. I was reminded that the liturgy as a whole is seen as an unfolding of a single event that incorporates both the Hours and Mass, but has the Mass at its centre. The quotation given to me mentioned in an earlier article comes to mind again here: the Mass is a jewel in its setting, which is the Liturgy of the Hours; and the Liturgy of the Hours also has its setting, which is the cosmos.

Further articles;

The Four Pillars of the New Liturgical Movement

Those who want to learn to do the Divine Office, you might approach a priest or religious (ie monk or nun) and ask them to show you. Alternatively, the Way of Beauty summer retreats at Thomas More College of Liberal Arts will teach you how to pray the Liturgy of the Hours and how you can realistically incorporated it into a busy working or family life

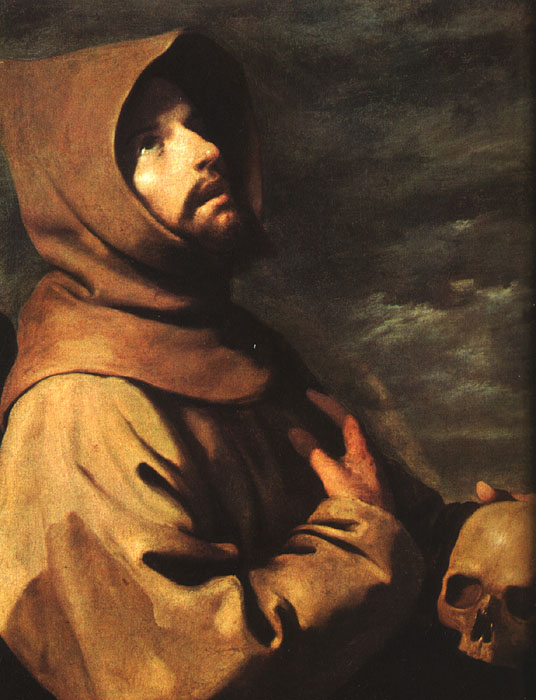

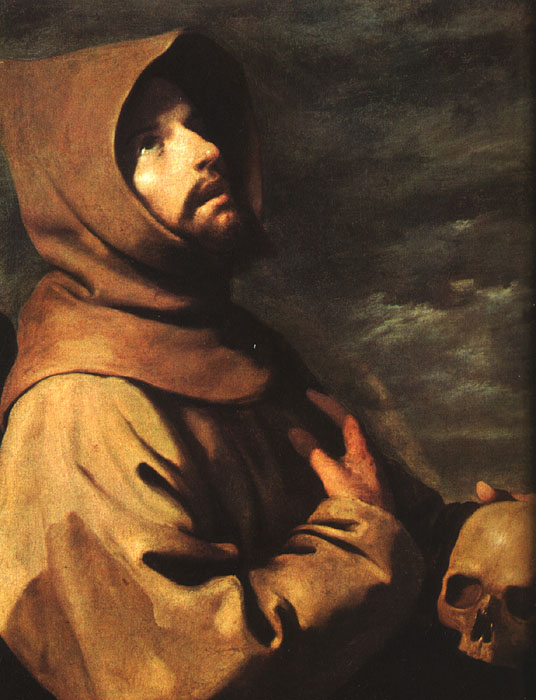

The Painting is of St Francis is by the 17th century Spanish artist Zurbaran

and, below, the Adoration of the Trinity by Albrecht Durer