How busy people can strive for the ideal of praying continuously. The Divine Office for lay people, part 2 (part 1 is here):

St Paul exhorts us: ‘Always rejoice. Pray without ceasing.’ (1 Thessalonians 5:16-17).

How busy people can strive for the ideal of praying continuously. The Divine Office for lay people, part 2 (part 1 is here):

St Paul exhorts us: ‘Always rejoice. Pray without ceasing.’ (1 Thessalonians 5:16-17).

How can we do this? One can imagine the heavenly host of angels and saints doing this as they participate in the heavenly liturgy. But how can we, while here in this earthly life, strive towards this ideal? The answer is the liturgy of the hours, also known as the Divine Office.

The Church’s General Instruction on the Liturgy of the Hours reads as follows:

"Consecration of Time

10. Christ taught us: "You must pray at all times and not lose heart" (Lk 18:1). The Church has been faithful in obeying this instruction; it never ceases to offer prayer and makes this exhortation its own: "Through him (Jesus) let us offer to God an unceasing sacrifice of praise" (Heb 15:15). The Church fulfills this precept not only by celebrating the Eucharist but in other ways also, especially through the liturgy of the hours. By ancient Christian tradition what distinguishes the liturgy of the hours from other liturgical services is that it consecrates to God the whole cycle of the day and the night. [56]

11. The purpose of the liturgy of the hours is to sanctify the day and the whole range of human activity.'' [My emphasis]

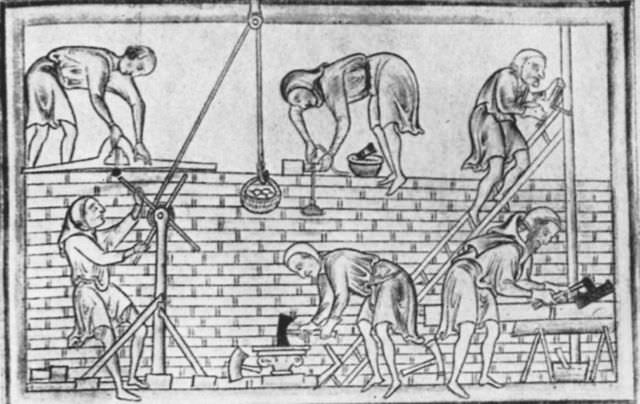

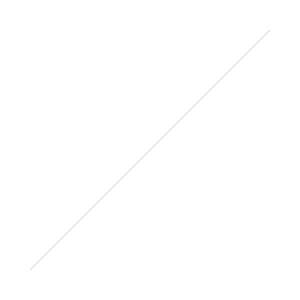

If all times in the day and all human activity (no matter how mundane) can be sanctified by praying the liturgy of the hours, as the Church tells us, then this is this is a wonderful gift by which we can open ourselves up to God’s inspiration and consolation in all we do, and the degree that we cooperate, all our activities will be good and beautiful; and will be infused with new ideas and creativity. And we will have joy.

If all times in the day and all human activity (no matter how mundane) can be sanctified by praying the liturgy of the hours, as the Church tells us, then this is this is a wonderful gift by which we can open ourselves up to God’s inspiration and consolation in all we do, and the degree that we cooperate, all our activities will be good and beautiful; and will be infused with new ideas and creativity. And we will have joy.

There are seven liturgical hours to be marked in the day and by tradition the process of doing something seven times symbolizes doing it perfectly or continuously. So for example, the psalmist (Ps 12:6) tells us that, ‘The words of the Lord are pure words: like silver tried by fire, purged from the earth refined seven times.’ This pattern of cycles of seven runs through the liturgy (see previous article, The Path to Heaven is a Triple Helix).

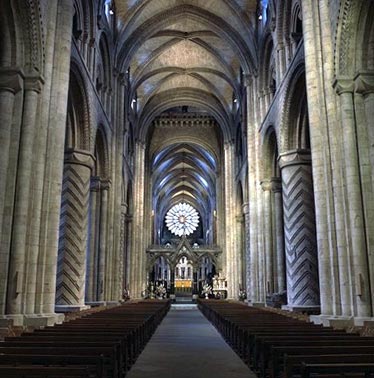

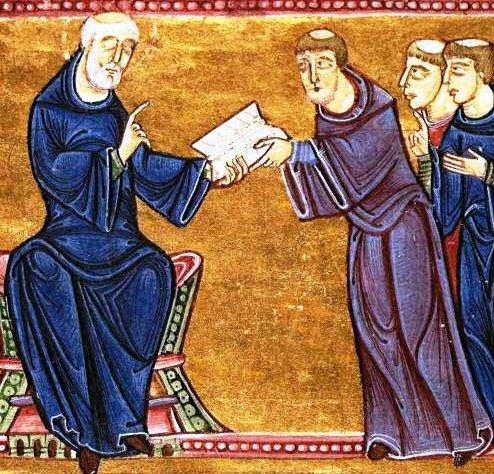

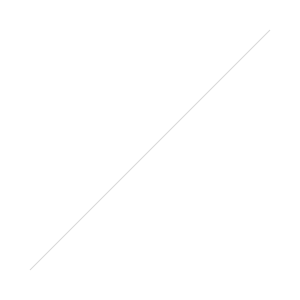

Even if we accept this and want to benefit from it, it is a huge problem for most lay people. If you get the full cycle of prayer of seven Offices in the day for seven days of every week in the year it adds up to a three or four volume set. Priests and religious who are obliged to pray it, devote a huge part of their lives to praying the liturgy of the hours. Benedictine monks can spend up to six hours a day singing the psalms in church. One might expect them to be able to cope as that is their special calling, but what about the rest of us?

Even if we accept this and want to benefit from it, it is a huge problem for most lay people. If you get the full cycle of prayer of seven Offices in the day for seven days of every week in the year it adds up to a three or four volume set. Priests and religious who are obliged to pray it, devote a huge part of their lives to praying the liturgy of the hours. Benedictine monks can spend up to six hours a day singing the psalms in church. One might expect them to be able to cope as that is their special calling, but what about the rest of us?

This is how I approached the problem. First, as with all these things the help of a spiritual director is invaluable. He told me that I should take heart in the fact that through its priests and religious especially, the Church as a whole is praying the Hours on our behalf. As the globe turns, someone somewhere is praying for all of humanity (most of whom have no idea of the benefits they are getting as a result). So any additional contribution that I might make, no matter how small, to this prayer of Christ in the mystical body, the Church, will be good, but neither is everything going to collapse if I don't do it perfectly. Even one Hour (or ‘Office’) a week is worth it.

I was told to start modestly. If I found it beneficial, then I was told that I could increase what I did, but then it would be best to do so only gradually. There was a danger that if I took on too much too early that I would find it overwhelming and then give up altogether.

I started by aiming to read a maximum of two each day: Morning Prayer (‘Lauds’) when I got up and Night Prayer (‘Compline’) before I went to bed. I had a single volume version that just had Lauds, Evening Prayer (Vespers) and Compline for the year. If you want to try this but don’t even want to buy a book, you can see what each Office is for any day by going to www.universalis.com.

Mark the Hours

Mark the Hours

It took me a while to develop this habit, but once I had, I had to decide what to do next? I'd experienced enough to know that this was good and I knew I wanted to do more. But, like many busy people it seemed to me that trying to introduce even just Vespers on top of what I was already doing was going to be difficult. I was given an alternative. If at any time I could not recite a full Office, why not substitute it with a memorized prayer, and aim gradually to mark each Hour and aim for the ideal of sevenfold prayer each day?

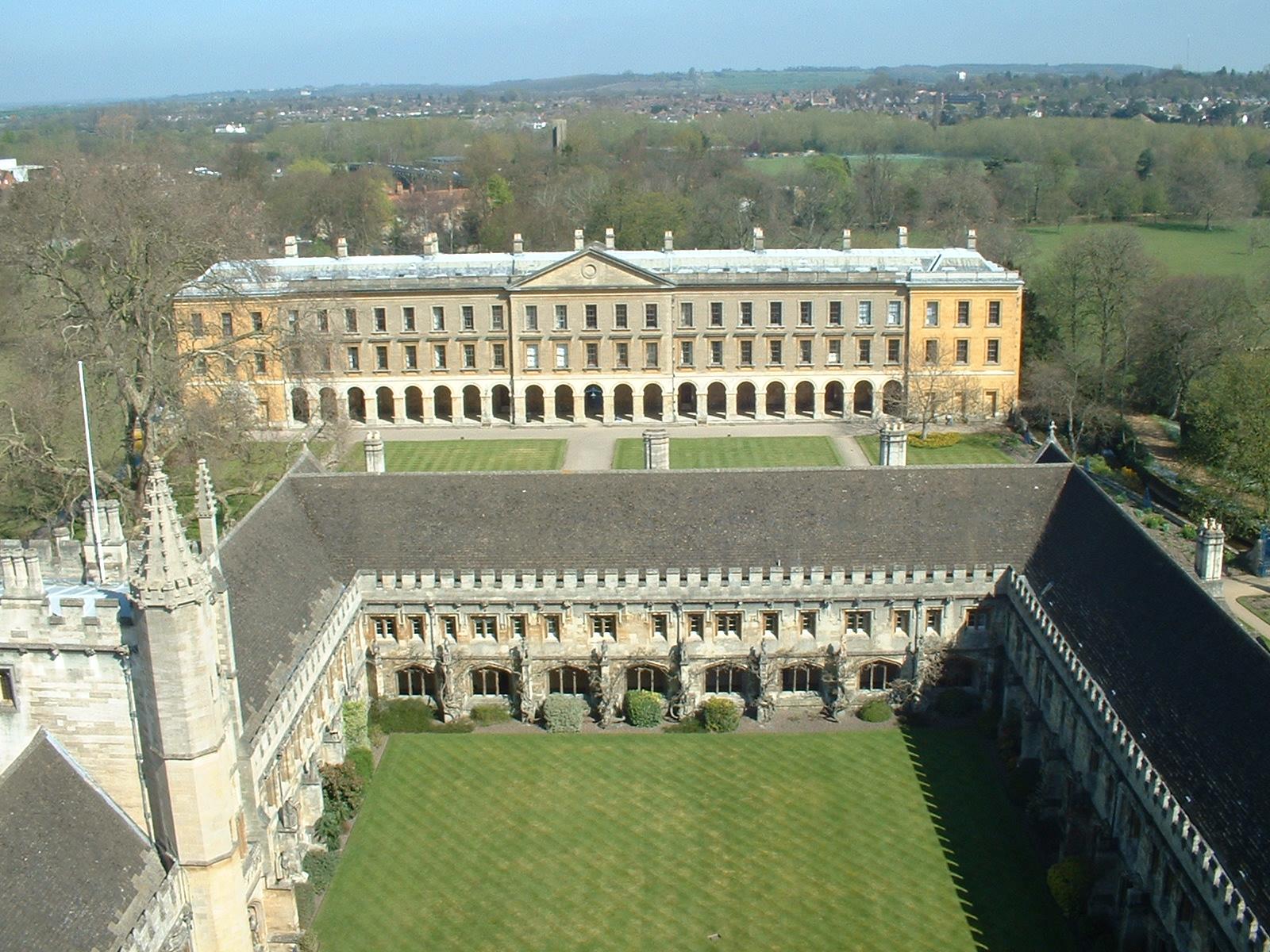

I was helped by reading a book recommended to me by a fellow faculty member of Thomas More College of Liberal Arts called Earthen Vessels, the Practice of Personal Prayer According to the Patristic Tradition, by Fr Gabriel Bunge. Despite its daunting title it is in fact quite easy to read and very practical. Fr Bunge a Swiss Benedictine monk explains that the essence of the liturgy of the hours can be described as two things: first praying the psalms; and second, the marking of an hour. The official ‘off-the-shelf’ cycles of psalms, canticles, hymns and prayers are produced to allow people to sing in community, and this is why priests and religious must say a prescribed form. However, as lay people, we are free to devise any cycle of the psalms we like.

So this is what I did: for the most part I tried to keep to the standard form of each Office as in the Liturgy of the Hours book I had been given (which was according the Roman Rite, it said in the front) and from that to the schedule of Compline at night and Lauds in the morning. However, in between I marked the hour with a short memorised prayer, sometimes just the Our Father, Hail Mary and Glory Be. If I could remember any, I tried to have just a line from a psalm. The ideal would be to memorise one psalm (and some are short!). This habit of continual prayer is what opens the door to the possibility of continuous prayer. The publication Magnificat is a cycle of the psalms, with some prayers and canticles, that one can subscribe to monthly, which has been designed with lay people in mind.

So this is what I did: for the most part I tried to keep to the standard form of each Office as in the Liturgy of the Hours book I had been given (which was according the Roman Rite, it said in the front) and from that to the schedule of Compline at night and Lauds in the morning. However, in between I marked the hour with a short memorised prayer, sometimes just the Our Father, Hail Mary and Glory Be. If I could remember any, I tried to have just a line from a psalm. The ideal would be to memorise one psalm (and some are short!). This habit of continual prayer is what opens the door to the possibility of continuous prayer. The publication Magnificat is a cycle of the psalms, with some prayers and canticles, that one can subscribe to monthly, which has been designed with lay people in mind.

What are the Hours?

The hours are not set times according the clock, but to the traditional organisation of time in which, roughtly speaking, usual hours of daylight are broken up into twelve divisions. So it is roughly like this: Lauds at dawn or when you get up; Terce (the ‘third hour’)at 9am or mid-morning, Sext (the ‘sixth’ hour) at noon or the middle of the day, None (at the ‘ninth’ hour)at 3pm or mid afternoon and Vespers at dusk. Then there is Compline at bed time and during the night Matins, which is also called the Office of Readings. Because busy people are not expected always to be able to rise at midnight to praise God, this can be said at any convenient time and is often run together with Lauds, first thing in the morning.

The experience of doing this has been so positive that I can't imagine not wanting to pray at least part of the Hours each day. As someone said to me recently, he found that the praying of the liturgy of the hours was like regular physical exercise: although it meant an investment of time, there was a sense that in doing so, time was created because work seemed more efficient and productive and things just seemed to go more smoothly during the day. We both felt the same. We couldn’t prove it, but once we had tried it, we were convinced of its value.

The experience of doing this has been so positive that I can't imagine not wanting to pray at least part of the Hours each day. As someone said to me recently, he found that the praying of the liturgy of the hours was like regular physical exercise: although it meant an investment of time, there was a sense that in doing so, time was created because work seemed more efficient and productive and things just seemed to go more smoothly during the day. We both felt the same. We couldn’t prove it, but once we had tried it, we were convinced of its value.

I started doing the liturgy of the hours about 15 years ago and gradually, I have found that my life circumstances have altered to give room for it. I don’t do it all perfectly, but I now do most Offices each day. It does not feel like a burden, but a source of sustenance.

Psalm 116

O praise the Lord, all ye nations: praise him, all ye people. For his mercy is confirmed upon us: and the truth of the Lord remaineth for ever.

You can read a more detailed article about it by following the link: Achieving the Pauline Ideal - Praying Continuously Body and Soul.

Those who want to learn to do the Divine Office, you might approach a priest or religious (ie monk or nun) and ask them to show you. Alternatively, the Way of Beauty summer retreats at Thomas More College of Liberal Arts will teach you how to pray the Liturgy of the Hours and how you can realistically incorporated it into a busy working or family life

The Liturgy is the most powerful and effective form of prayer.

The Liturgy is the most powerful and effective form of prayer.

Engaging the Whole Person in Prayer Opens us up Further to Inspiration and Creativity - The Divine Office III,

Engaging the Whole Person in Prayer Opens us up Further to Inspiration and Creativity - The Divine Office III,  If in the context of the Liturgy our continuous prayer simultaneously engages the whole person then can we are opening ourselves up to the greatest degree possible to God’s grace. To the degree that we cooperate with grace this will help us make all our life decisions and help us to move towards the fulfillment of our personal vocation in life. This will be perfectly ordered also to the model of charity, that is, love of God. To the degree that we match these standards there will be perfect harmony with the objective standard of God’s will. This is the supernatural path to inner peace, peace with our neighbour and a life in harmony with creation.

If in the context of the Liturgy our continuous prayer simultaneously engages the whole person then can we are opening ourselves up to the greatest degree possible to God’s grace. To the degree that we cooperate with grace this will help us make all our life decisions and help us to move towards the fulfillment of our personal vocation in life. This will be perfectly ordered also to the model of charity, that is, love of God. To the degree that we match these standards there will be perfect harmony with the objective standard of God’s will. This is the supernatural path to inner peace, peace with our neighbour and a life in harmony with creation. Chant:

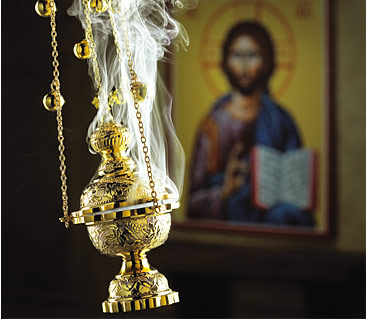

Chant: Incorporating the sense of smell

Incorporating the sense of smell

How busy people can strive for the ideal of praying continuously. The Divine Office for lay people, part 2 (

How busy people can strive for the ideal of praying continuously. The Divine Office for lay people, part 2 ( If all times in the day and all human activity (no matter how mundane) can be sanctified by praying the liturgy of the hours, as the Church tells us, then this is this is a wonderful gift by which we can open ourselves up to God’s inspiration and consolation in all we do, and the degree that we cooperate, all our activities will be good and beautiful; and will be infused with new ideas and creativity. And we will have joy.

If all times in the day and all human activity (no matter how mundane) can be sanctified by praying the liturgy of the hours, as the Church tells us, then this is this is a wonderful gift by which we can open ourselves up to God’s inspiration and consolation in all we do, and the degree that we cooperate, all our activities will be good and beautiful; and will be infused with new ideas and creativity. And we will have joy. Even if we accept this and want to benefit from it, it is a huge problem for most lay people. If you get the full cycle of prayer of seven Offices in the day for seven days of every week in the year it adds up to a three or four volume set. Priests and religious who are obliged to pray it, devote a huge part of their lives to praying the liturgy of the hours. Benedictine monks can spend up to six hours a day singing the psalms in church. One might expect them to be able to cope as that is their special calling, but what about the rest of us?

Even if we accept this and want to benefit from it, it is a huge problem for most lay people. If you get the full cycle of prayer of seven Offices in the day for seven days of every week in the year it adds up to a three or four volume set. Priests and religious who are obliged to pray it, devote a huge part of their lives to praying the liturgy of the hours. Benedictine monks can spend up to six hours a day singing the psalms in church. One might expect them to be able to cope as that is their special calling, but what about the rest of us? Mark the Hours

Mark the Hours So this is what I did: for the most part I tried to keep to the standard form of each Office as in the Liturgy of the Hours book I had been given (which was according the Roman Rite, it said in the front) and from that to the schedule of Compline at night and Lauds in the morning. However, in between I marked the hour with a short memorised prayer, sometimes just the Our Father, Hail Mary and Glory Be. If I could remember any, I tried to have just a line from a psalm. The ideal would be to memorise one psalm (and some are short!). This habit of continual prayer is what opens the door to the possibility of continuous prayer. The publication

So this is what I did: for the most part I tried to keep to the standard form of each Office as in the Liturgy of the Hours book I had been given (which was according the Roman Rite, it said in the front) and from that to the schedule of Compline at night and Lauds in the morning. However, in between I marked the hour with a short memorised prayer, sometimes just the Our Father, Hail Mary and Glory Be. If I could remember any, I tried to have just a line from a psalm. The ideal would be to memorise one psalm (and some are short!). This habit of continual prayer is what opens the door to the possibility of continuous prayer. The publication  The experience of doing this has been so positive that I can't imagine not wanting to pray at least part of the Hours each day. As someone said to me recently, he found that the praying of the liturgy of the hours was like regular physical exercise: although it meant an investment of time, there was a sense that in doing so, time was created because work seemed more efficient and productive and things just seemed to go more smoothly during the day. We both felt the same. We couldn’t prove it, but once we had tried it, we were convinced of its value.

The experience of doing this has been so positive that I can't imagine not wanting to pray at least part of the Hours each day. As someone said to me recently, he found that the praying of the liturgy of the hours was like regular physical exercise: although it meant an investment of time, there was a sense that in doing so, time was created because work seemed more efficient and productive and things just seemed to go more smoothly during the day. We both felt the same. We couldn’t prove it, but once we had tried it, we were convinced of its value.

An ancient beautiful prayer that leads us to joy, and opens us up to inspiration and creativity; part 1,

An ancient beautiful prayer that leads us to joy, and opens us up to inspiration and creativity; part 1,  If we pray in harmony with rhythms and patterns of the cosmos, especially the cycles of the the sun, the moon and the stars, then the whole person, body and soul, is conforming to the order of heaven. The daily repetitions, the weekly, monthly and season cycles of the liturgy allow us to do just that. In his book, the Spirit of the Liturgy, Pope Benedict XVI calls our apprehension of this order, when we see the beauty of Creation a glimpse into 'the mind of the Creator'. This conformity in prayer opens us up so that we are drawing in the breath of the Spirit, so to speak, as God chooses to exhale. It increases our receptivity to inspiration and God’s consoling grace and leads us more deeply into the mystery of the Mass.

If we pray in harmony with rhythms and patterns of the cosmos, especially the cycles of the the sun, the moon and the stars, then the whole person, body and soul, is conforming to the order of heaven. The daily repetitions, the weekly, monthly and season cycles of the liturgy allow us to do just that. In his book, the Spirit of the Liturgy, Pope Benedict XVI calls our apprehension of this order, when we see the beauty of Creation a glimpse into 'the mind of the Creator'. This conformity in prayer opens us up so that we are drawing in the breath of the Spirit, so to speak, as God chooses to exhale. It increases our receptivity to inspiration and God’s consoling grace and leads us more deeply into the mystery of the Mass.

Scripture, Part of the Foundation of Joy (part three; part one

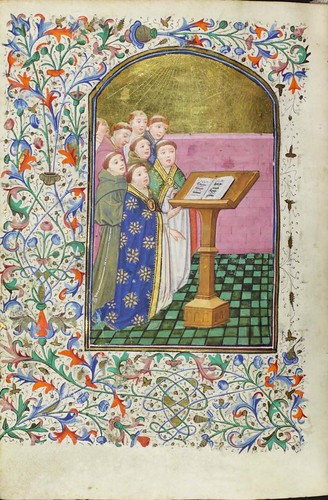

Scripture, Part of the Foundation of Joy (part three; part one  And so whenever anyone discovers some part of the treasure, he should not think that he has exhausted God’s word. Instead he should feel that this is all that he was able to find of the wealth contained in it. Nor should he say that the word is weak and sterile or look down on it simply because this portion was all that he happened to find. But precisely because he could not capture it all he should give thanks for its riches.

And so whenever anyone discovers some part of the treasure, he should not think that he has exhausted God’s word. Instead he should feel that this is all that he was able to find of the wealth contained in it. Nor should he say that the word is weak and sterile or look down on it simply because this portion was all that he happened to find. But precisely because he could not capture it all he should give thanks for its riches.

Scripture, Part of the Foundation of Joy (part two; read part one,

Scripture, Part of the Foundation of Joy (part two; read part one,

This leads to the third stage, Oratio – prayer. So here I can ask God to show me how to act on something or help me in those areas that the meditation highlighted. The worry for me here was that sometimes I didn’t seem to have any profound lessons or thoughts to react to. This meant I didn’t know what to pray, except perhaps, ‘please give me some profound lessons or thoughts’. Here again I was given some helpful advice by someone with much greater experience than me. He said that quite often this happened to him and he didn’t think it was anything to worry about, he simply said some prayers in which he praised God for having this chance to hear his Word.

This leads to the third stage, Oratio – prayer. So here I can ask God to show me how to act on something or help me in those areas that the meditation highlighted. The worry for me here was that sometimes I didn’t seem to have any profound lessons or thoughts to react to. This meant I didn’t know what to pray, except perhaps, ‘please give me some profound lessons or thoughts’. Here again I was given some helpful advice by someone with much greater experience than me. He said that quite often this happened to him and he didn’t think it was anything to worry about, he simply said some prayers in which he praised God for having this chance to hear his Word.

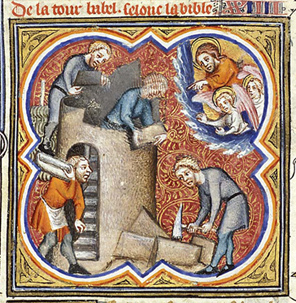

Scripture, part of the foundation of joy (part one, part two tomorrow)

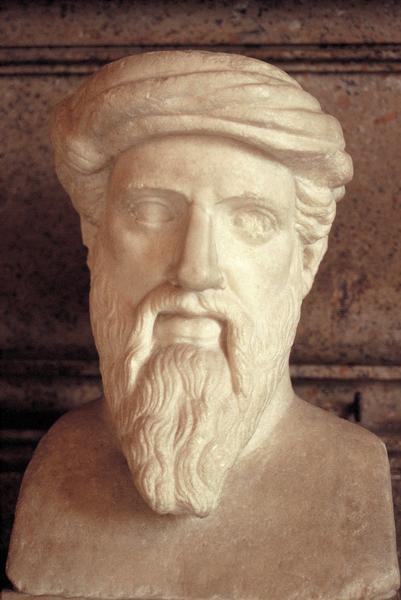

Scripture, part of the foundation of joy (part one, part two tomorrow) Here is St Bonaventure (whose picture is shown) from the Office of Readings of Monday Week 5 of the year:

Here is St Bonaventure (whose picture is shown) from the Office of Readings of Monday Week 5 of the year: