The Christian connection between culture, conservative values, the common good and the natural law

In my post one week ago (entitled What is Culture), I described how a beautiful culture emerges through the loving interaction of the people in a society and their love of God. Now, love is by nature freely given (the moment we are compelled to love, it is no longer love!). Therefore, freedom - the freedom to love God and neighbor - is a necessary condition for a beautiful culture.

What is freedom? Many feel that freedom is simply the absence of constraint and compulsion. That is part of it, but the traditional approach has a deeper understanding. We can define freedom in the traditional understanding as the capacity to choose the practicable best. For us to be in full possession of freedom and be able to choose the course that is best, therefore, three components must be present.

The first component is the absence of constraint or compulsion; the second is a full knowledge of what is best for us; and the third is the power to act in accordance with what is best. The good that is best for each of us in the context of a society is known as the ‘common good’. When we act in accordance with the common good then we also do what is best for ourselves. In the proper order of things, the personal good and the common good are never in conflict with each other. The most obvious guides to seeking the common good are the moral law and the principles of justice as prescribed by Christ’s Church. All authentic and beautiful Christian cultures emerge from the freely taken actions of the members of a society toward the common good.

The Capitol Building, Washington DC. This building has become emblematic of America and American values

It is in the interest of a Cristian society therefore to promote freedom by a system of laws that are just and so give security to the individual to act in accordance with the freedom to be moral and good. Such a system of laws would be directed to restraining people from interfering with the freedom of others. The state also encourages the formation of people through an education that will help them to know the common good. The state fulfils its role by enabling good teachers, and most especially parents as teachers of the children, to teach well. If these conditions are satisfied then I believe a culture of beauty will emerge organically from the bottom up.

Analogously, and in regard to supporting the arts themselves, I believe that it is better to strive to create the conditions that promote the freedom to pursue art as a career, than to try to impose the elitist vision of what art ought to look like onto people from the top down. The freedom given to an artist in this context is understood as consisting of a knowledge of what sort of art might benefit the society and the skill and means to create it. A top down imposition of artistic standards, almost always tends to restrict freedom and so undermines the chance of creating an authentically beautiful culture.

One might think that an exception to this rule might be those arts that are to be used directly by government, for example the design of civic buildings, for which government must, by necessity, be involved. However, even then the government ought to be mindful that it serves the people and does not direct them, and hence be aware both of tradition (the people of the past) and what most people want. Also, because architecture and public spaces have an impact on the whole community and not just those who occupy them, then the community that it will impact most immediately must have a say on the style of buildings. The authority that specifies such buildings must reflect the principle of subsidiarity as far as possible. A State Capitol building should reflect what the people of the state want and used to want ie tradition, while the small city government would select the architecture for the town hall, reflecting what the neighborhood wants.

Boston public library

For example, the Hungarian government recently undertook a building program to replace the brutalist style of communist built buildings in its capital Budapest with more elegant architecture. In the last 10 years it has rebuilt or rennovated in the style that is in accord with the traditional architecture of the city, and this has been a highly popular building program. Furthermore, the level of tourism in the city has increased dramatically, with the new buildings being the attractions as much as the old.

Returning to our focus on the role of the state and its connection to culture: the pattern of positive law (those laws created by human government) of a society will inevitably be different from one nation to another even for those nations that are seeking to create laws for all the right reasons. The truths of the natural law which inform positive law are eternal and universal principles; but this universality of the principles themselves does not mean that human society immediately and instantaneously comes to know and apply these principles universally, in all places, in exactly the same way. Human knowledge, like human society, must progress slowly, in stages, step-by-step, and organically, or else it is not a true "human society" at all. It does so through a process of trial and error, gradually seeing what works best. Therefore each society will take a different path towards this knowledge.

The good Christian society recognizes the difficulty of knowing fully, and applying well, the universal principles of the natural law and thus the good Christian society seeks the aid of revelation, Tradition, and the experience of past laws to help guide reason. God revealed truths for two reasons, St Thomas Aquinas tells us, first because some truths are beyond the grasp of reason (for example, the Trinity, the Incarnation, the resurrection of the body); and second, God also revealed moral truths that, although part of the natural law and accessible to natural reason, would “only be discovered by a few, and that after a long time, and with the admixture of errors” (ST Ia Q1,1 co.). Arising from this there are two important reasons why the pattern of the exercise of freedom will be different from one Christian nation to another. First, principles that are understood well can still be applied in different ways by different societies without contravening those principles; and second, the knowledge or understanding of a principle is very likely not perfect or full and will vary from nation to nation, each thinking that it knows best.

Accordingly, different Christian nations are free to observe the experience of other nations, imitate what is best in them, and adopt what is beautiful and good from them. This way, in the proper order of things, each nation is part of a family of distinct and autonomous nations, each helping each other to find what is best.

As mentioned in my earlier post, a culture is a sign of the core values of the society that produces it and as such it is beautiful to the degree that it is Christian. This is true even in those societies or countries that would not think of themselves as Christian. An Islamic nation, for example, has a beautiful culture to the degree that its culture is consistent with an expression of the Christian truths even when those truths are communicated to them by the Koran.

Further, it is the Christian characteristics of different cultures that connect them to each other; and it is the different national expressions of that Christian faith manifested in characteristic patterns of loving interraction and free behaviour that distinguish different Christian cultures from each other.

So for example, historically, the United States began as a nation that adopted and then adapted a system of law from the English constitutional tradition. The English constitutional tradition is a system of laws, rooted in Christian values, yet expressed in a characteristically English way that is quite different from, for example, that of its neighbor France. In time the American system of law developed its own national characteristics, while still owing much to its English beginnings, but now expressing it in a characteristically American way. If American culture is to be transformed into one of beauty it will be one that asserts the importance of America as a distinct nation with characteristic values that are simultaneously Christian and of a particular American-English expression. As such one would expect to see similarities to English culture in American culture. It is no accident for example, that in the latter part of the 19th century and early 20th century, American churches and universities were modeled on the English neo-gothic style. They even hired English architects to build them, but quickly an American character emerged from these and so while we can see the similarities between Princeton and Oxford universities, one reflects America while the other reflects England. All this was before the decline of the culture in both America and England, which took hold strongly after the second world war, and by which both nations lost a sense of importance of the Christian faith to the defining principles of their nations, and the principles of common law that underlay each.

Oxfprd

Yale

Princeton

The task of transforming the culture in our country, America, then, is clearly one of evangelization. We hope for and work towards a society in which the culture’s ordering principle is the transfigured Christ. And people must be aware again of what that looks like in America. This latter aspect requires more than an understanding of the principles of the American constitution. It requires an appreciation also of the cultural mileau from which it emerged and a love for it.

How do we do this? Education and other factors are important, of course; I have devoted much of what I do to education for just this reason. But once again, the greatest contribution that each of us can make is to play our own part in relating to others as good Christians and good Americans. When we do this we can conform more closely to our supernatural end, through grace and participation in the sacramental economy and we do so as Christians and as Americans.

For all American Christians, the most powerful influence on the transmission and retention of the Christian faith is its worship. For American Catholics in particular worship by participation in the Mass and the Liturgy of the Hours. This principle of the pre-eminence of worship in retaining and transmitting faith is articulated by the Church Fathers with the phrase lex orandi, lex credendi which means rule of prayer, rule of faith. It says that our prayers and especially those in the context of the liturgy which is the highest form of prayer, influence most strongly what we believe. This phrase originates, tradition tells us, with Prosper of Aquitaine who was a disciple of St Augustine in the 4th century.

People today, who very likely have never heard of Prosper of Aquitaine, know instinctively how important worship is to the Christian faith. This is why fights over the content and style with which the liturgy is celebrated are so emotional and at times embittered. This is not a sideshow, it really does matter. It is the primary battleground in the fight for Christian culture. Those who hate the Church know this too and will do all they can to undermine the freedom to worship God.

And visual art has a vital and necessary part to play in our worship. Art therefore is not a matter to be considered only by aesthetes, it plays a vital role in the well being of the Church and therefore of society as a whole. Thus beautiful and dignified liturgy, along with the re-establishment of art forms in harmony with it, are a constant need for the well-being of the Church and the nations of the world.

In summary, if we accept that the liturgy has the greatest influence on our faith, and our faith has the greatest influence on the culture, then we can see that it is the liturgy, (rather than for example socio-economic factors), that is the greatest positive influence on the wider culture. Other factors can have an impact, but authentic worship is the wellspring of Christian culture, and its primary influencer is Christ Himself.

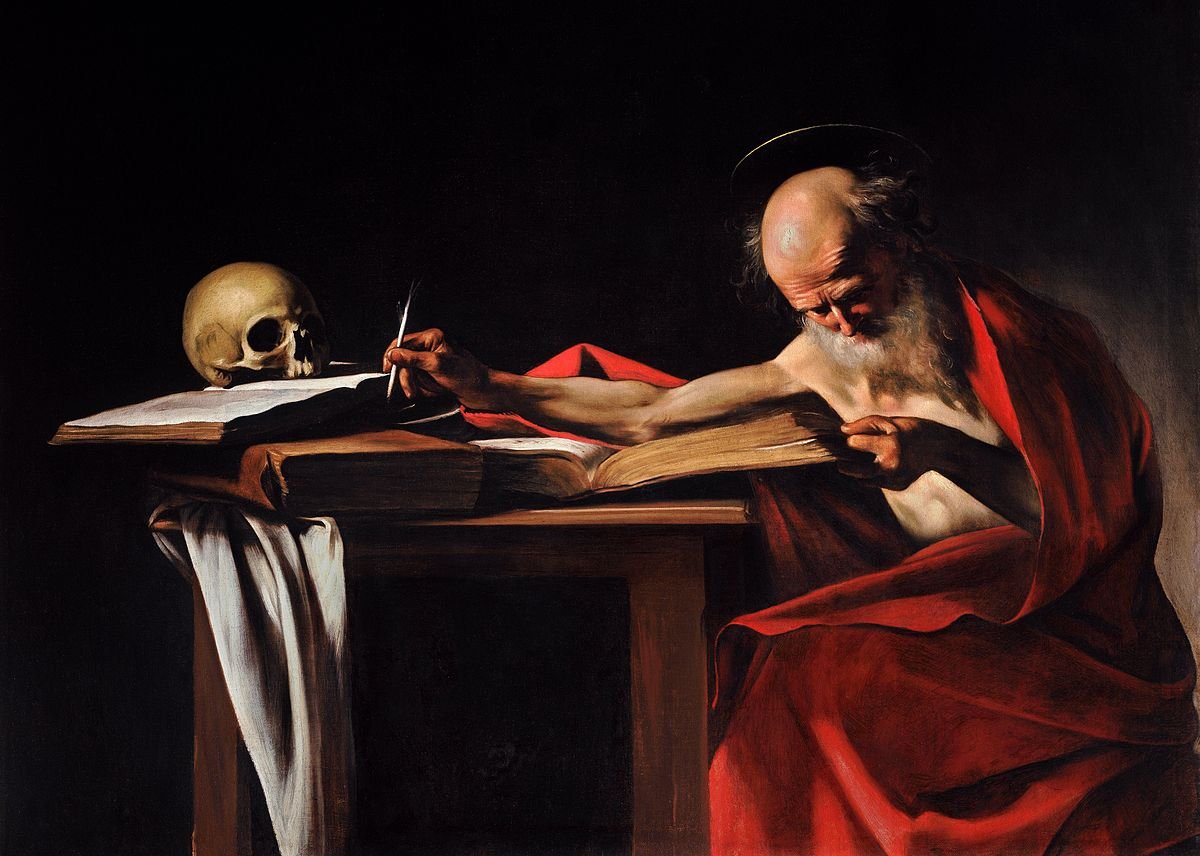

It is this principle that informs our understanding of what the purpose of art ought to be. It must inspire and inform our worship first, and then the whole of our Christian lives through its beauty. It has been said that all the great art movements began on the altar. So, for example, baroque art began as a style of sacred art in Italy with great painters such as Caravaggio and Frederico Barocci, who created art as servants of the Church to aid worship in the liturgy.

The Circumcision by Frederico Barocci, c 1590

St Jerome by Caravaggio

Once established however, baroque art quickly became the standard for non-religious art too. Portraits, landscapes and still lives were painted in the baroque style too. Such was the beauty of these works that Protestants decided that they wanted to paint in this style too. Rembrandt and the Dutch masters were inspired by the new Italian style of Catholic sacred art to paint as they did. A young Flemish master, Anthony van Dyck was commissioned by King Charles 1 of England to paint portraits of the royal household and from his work came the English portrait tradition. It was in mimicry of the English portrait tradition that the famous portraits of the founding fathers of the US, such as George Washington were painted, establish an American tradition of its own. It was the the great beauty of baroque art that persuaded also patrons to commission works in this style. The same effect was observed in music and architecture and by this the culture of 17th-century Europe became universally baroque and through its style always spoke in some way of Christ, even when the subject painted was something more mundane.

Rembrandt self portrait

Sir Anthony van Dyck, self portrait

To transform the American culture, therefore, we American Christians must worship well, draw others to our faith by our conduct and love for them and strive for art forms that connect with our worship. The most beautiful art forms that emerge from this will dominate eventually because its beauty will persuade all Christians that it is what they want. This will then become the driving force for contemporary culture that is informed by and speaks of the faith and the values of the Christianity in a uniquely American way.

In the Office of Readings, which is part of the Liturgy of the Hours, on the Feast of the Epiphany the second reading is from a sermon by Pope St Leo the Great. The passage closes with the following words:

‘Dear friends, you must have the same zeal to be of help to one another; then, in the kingdom of God, to which faith and good works are the way, you will shine as children of the light: through our Lord Jesus Christ, who lives and reigns with God the Father and the Holy Spirit for ever and ever. Amen.’

Our lives and our whole life’s work - and art is part of this - must participate in this Light. If we can move towards this ideal even partially, then the effect will be irresistible. And our Christian worship is the engine that drives us forward to the Light.

John Adams painted by Gilbert Stuart