The reason for my choice in the latest of this series of artists who successfully followed tradition and by doing so went against the trends of their time may surprise some. Many will assume that his style of naturalism spoke for the mainstream in art around the turn of the last century. But as we will see, he went against the mainstream and made his style dominant. By the time of his death in 1925, he was one of the most famous artists of his day. After his death, however, his work quickly fell out of favor in the years that followed his death because he was not progressive or modern enough. For example, one of his most famous series of paintings, the wall paintings in the Boston Public Library entitled The Triumph of Religion, completed in 1919, was neglected and almost destroyed. and it is only in the last 30 years or so that his reputation as a great artist of the past has waxed once again.

When an 18-year-old Sargent chose the studio in which to draw and paint, in Paris in 1874 he did not select the French Academy, who favored a strongly classical influenced style. Nor did he choose to follow the style of the emerging Impressionists (whose first show took place the same year). Rather, he looked back to the baroque style of the 17th-century Spanish school, which was epitomized by the great master, Velazquez.

J D Rockefeller, by John Singer Sargent

To the modern eye, accustomed to the brutalizing ugliness of modern styles, these three options seem similar. Each is naturalistic and requires a high level of drawing skill compared to what is needed to graduate from the art schools of our universities today. However, there are three distinct worldviews behind them and when one style finally came to dominate the art world - the loose focussed style of the Impressionists - it quickly devolved into the artistic forms of modernity that are intended to undermine and speak against traditional Western values.

First, consider the clean-edged and brightly colored look of the Academy (reminiscent of Raphael from the High Renaissance). This style had dominated the French Academy since, Davide, Napoleon's favored artist of the Revolution, introduced it. It is intended to represent the anti-Christian, rationalism of the Continental Enlightenment and, rejecting the need for Revelation in the search for truth and justice, identified itself with pre-Christian classicism. It sought also to identify the State with the grandeur and power of Imperial Rome.

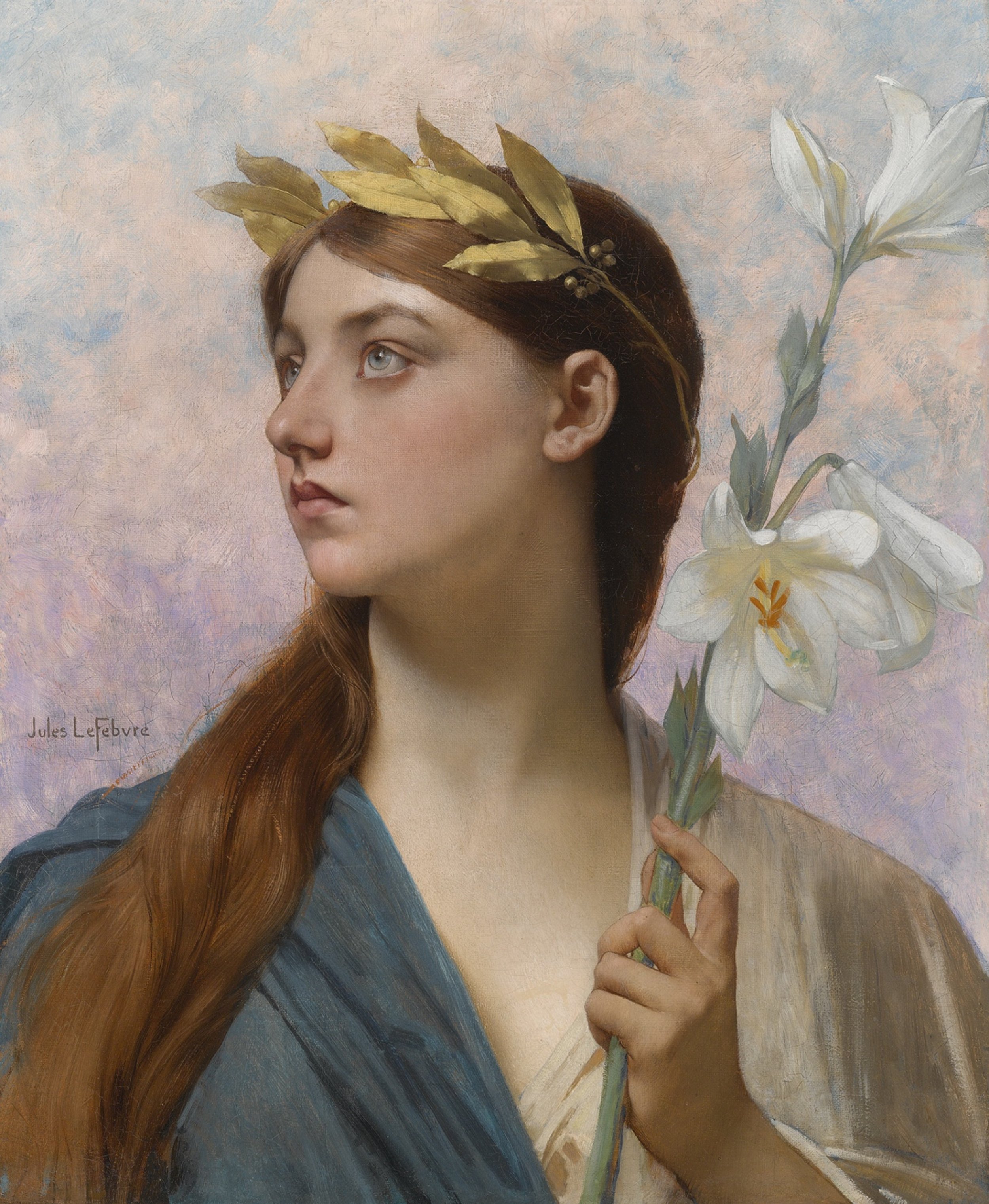

Jules Lefebvre, French, late 19th century: An Allegory of Victory

There are paintings by artists who worked in this style depicting Christian scenes, such as those by Bougeureau, but as with all painting in which the content depicts a message in style that is not equipped to do so, the result is a forced sentimentalism. The modernist descendant of this style is photorealism in which every detail in a painting is represented in precise focus and creates an image that overloads the senses with detail.

There is a re-emergence of the teaching of Academic method in a number of art schools and studios around the country today, mostly outside the university system. While it is a good thing that such skill in drawing and painting is being taught once again, it is unfortunate that it is this particular style, often referred to as 'classical realism' is generally adopted also. We are starting to see paintings in this style appearing in in Catholic churches in the mistaken belief that they are re-establishing Christian traditions.

As a reaction against this style in the mid-19th century, you have the Impressionists, who were just beginning to become dominant at this time and whose work is so familiar today. The Impressionists claimed to look at a scene with radical disinterest. They did not see people, the sky and cows in a field, for example, but simply colors and light manifested by a single extended substance consisting of atoms and molecules. They tried to represent scenes so as to communicate this even disinterest and in contrast to the neo-classical style, their paintings had no focus at all. There is an absence of sharp edges. In practice, the Impressionists were poor at applying their own ethos because they could not escape the fact that they were highly trained artists who almost by instinct composed paintings well. So the Impressionists were popular for the beauty of their landscapes which was manifested despite, and not because of their ethos.

Claude Monet: The Grand Canal in Venice

A dividing line between these styles, one which balances idealism and realism as Christian styles ought to (as Pius XII described in Mediator Dei, 70 years later), is that of the baroque of the 17th century. This is why Benedict XVI describes this, and not neo-classicism, as an authentic liturgical Christian style.

This is the style that Sargent decided to paint in. It was not the dominant style of the period, but there were a few who sought to re-establish it, including the Sargent's teacher, Charles Durand, known as Carolos-Duran.

The baroque grew out of a Christian understanding of the world, in which there is a hierarchy of beings. So for a Christian, a person is not simply a collection of atoms but an entity that is distinct from other beings. When we look at any scene we have more interest in some parts, and this uneven interest usually reflects this hierarchy of being, which we observe instinctively. So we look at people before animals and animals before plants. This places people highest. Furthermore, when we look at people we look at those aspects that reveal to us that he or she has a soul, that is the eyes and the expression on the face, perhaps also the gesture that tells us what he is doing or thinking. A Christian representation of these things therefore, balances sharp edges and blurred detail, to create a sharp focus on those elements that are of greatest interest to us naturally. Through this subtle variation in focus, metaphysical truths are communicated by visible signs embedded into the painting.

If you look at the painting of the Crowning of the Virgin by Velazquez at first impression it looks sharp and clear but close inspection shows how loosely he paints those areas that are not the main focus, and that the face of the Virgin is rendered in the finest detail. This draws the eye naturally to the point that he wishes us to focus on primarily.

This Christian balance of idealism and realism is extraordinarily difficult to achieve and Sargent, though a highly gifted artist, had to study for years in Paris before going to the Prado, the art gallery in Madrid, Spain to copy every painting by the acknowledged master of the style, Velazquez. In so doing he made this style his own.

Sargent's motivation for the adoption this style was not, to my knowledge, religious. It was based upon an aesthetic that viewed this style as superior to all others because, and they were correct in this, it reflected an accurate understanding of how we observe things around us. It is the Christian who add that we do so because God made us to see a sign of Him in His work. R.A.M. Stevenson's book on Velazquez (published in 1895) describes the stylistic elements of the 17th-century artists as they were understood by those participating in his style in the 19th century, such as Sargent. It is an excellent reference book for anyone today who wishes to paint in this style, but he never mentions the Christian origins of the underlying philosophy. Additionally, and confusingly, he calls this style 'impressionism' but he is clear that he is not describing the style of Monet et al.

Ultimately, this lack of identification of the neo-baroque style with Christian principles left it vulnerable to attack from the modernists in the 20th century. After all, I can't defend the use of style if I don't know why I'm using it beyond, 'I like it.'