Good didactic art is simultaneously liturgical, and good liturgical art is simultaneously didactic.

The Sherborne Missal and the 14th-Century Artist Who Suffered for His Art

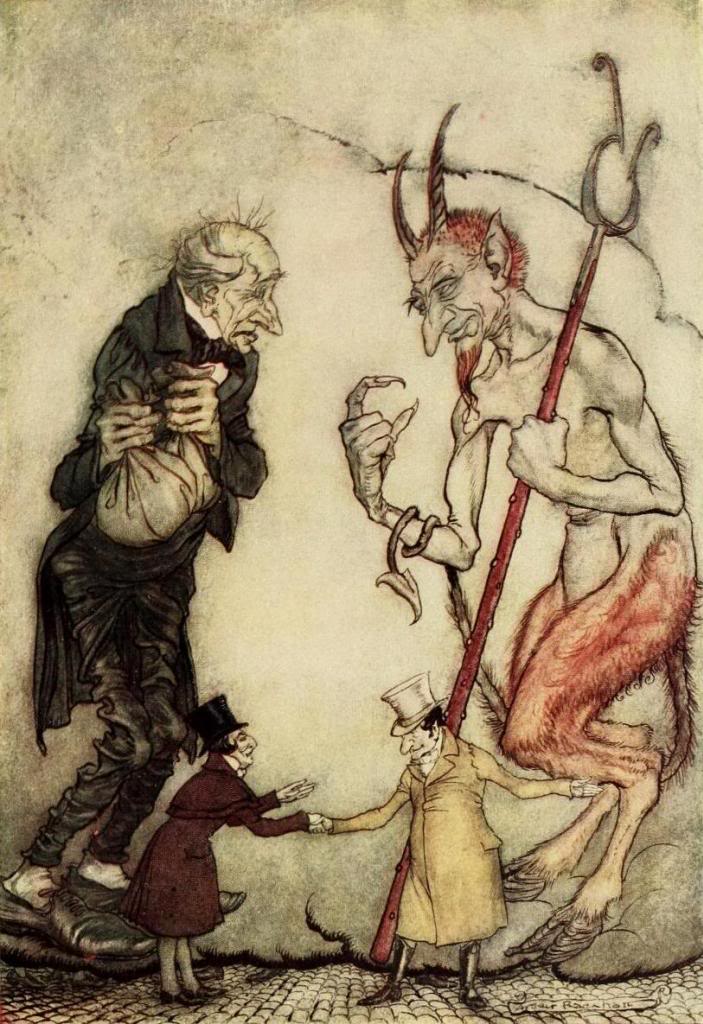

Arthur Rackham - A Brilliant Illustrator from the Golden Age of British Illustration

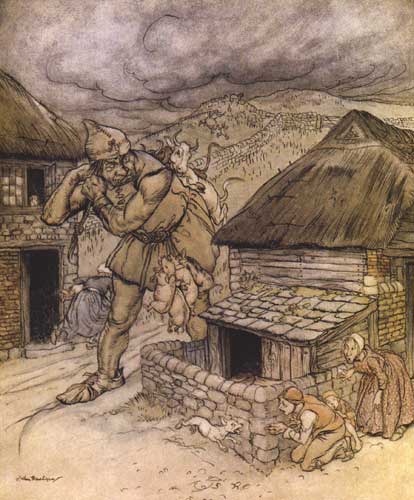

Following on from last week here are some more illustrations from England in the period of 10-15 years on either side of the First World War. This time the artist is Arthur Rackham. When I was young my Mum and Dad used to read Jack the Giant Killer to me. The book had been my Mum's when she was a girl. I loved these stories and the illustrations, by Arthur Rackham which were both terrifying and exciting for a little boy and have made a lasting impression on me. Books illustrated by him have become collector's items and very expensive. Here is one benefit of the internet. Having not seen anything by him for years (somehow that original family copy was lost) I googled him and found hundreds of images online - more than I had ever been aware of.

Following on from last week here are some more illustrations from England in the period of 10-15 years on either side of the First World War. This time the artist is Arthur Rackham. When I was young my Mum and Dad used to read Jack the Giant Killer to me. The book had been my Mum's when she was a girl. I loved these stories and the illustrations, by Arthur Rackham which were both terrifying and exciting for a little boy and have made a lasting impression on me. Books illustrated by him have become collector's items and very expensive. Here is one benefit of the internet. Having not seen anything by him for years (somehow that original family copy was lost) I googled him and found hundreds of images online - more than I had ever been aware of.

Arthur Rackham was born in 1867 and died of cancer in 1939. He had a formal art training in London and his work really started to be noticed at the turn of the last century. He was admired internationally and won gold medals at international art exhibitions and expositions, in Barcelona and Milan for example. You may not have heard of the name, but there is a good chance that you have seen some of his illustrations. As well as children's books such the one already mentioned, he created the well known images of Peter Pan, Jack and the Beanstalk, the Wind in the Willows (top left) and many, many fairy tales for children. Even if the image that comes to mind when you think of these stories from animated film, very often the basic image that the later animators used for the movie is drawn from Rackham's original depiction.

Arthur Rackham was born in 1867 and died of cancer in 1939. He had a formal art training in London and his work really started to be noticed at the turn of the last century. He was admired internationally and won gold medals at international art exhibitions and expositions, in Barcelona and Milan for example. You may not have heard of the name, but there is a good chance that you have seen some of his illustrations. As well as children's books such the one already mentioned, he created the well known images of Peter Pan, Jack and the Beanstalk, the Wind in the Willows (top left) and many, many fairy tales for children. Even if the image that comes to mind when you think of these stories from animated film, very often the basic image that the later animators used for the movie is drawn from Rackham's original depiction.

In this period, illustration was treated almost as high art. Very expensive, leather bound editions of books would be produced as collectors items. Clearly these collectors were usually not young children and so it was natural for the subjects of such editions to be extended to the publication of illustrated poetry and stories that adults would be interested in. For example he illustrated stories from Wagners' Ring Cycle, Shakespeare's plays and John Milton's Comus.

His method seems to have been one of doing detailed drawings in pencil first and then inking in and erasing the pencil lines. He then builds up tonal contrast with multiple washes of browns and ochres and selectively colors areas by a similar build up of multiple transparent washes. His description of form is primarily through line therefore; but he uses tone and colour as very strong supporting players and very skillfully in order to draw the eye of the observer to those areas of the painting that he wants to be primary foci. This is done through: variation in contrast - lights next to dark attracts attention; variation in focus - sharp edges attract attention more than soft edges; and variation in colour - coloured areas attract attention when contrasted with other areas that describe form tonally, usually in sepias and greys. Accounts of his work talk about his understanding of 'new developments' in printing techniques and how he developed a way of working that allowed him to take adantage of thes. To the modern artists, who never needs to think about the capacity of modern technology to reproduce his work, of course, it would seems as though Rackham was working within constraints created by the limitations of printing. That being so, Rackham's work is another example of the maxim that one of my painting teachers use to say when forcing us to work within a limited palette: that very often being forced to work within narrow lateral constraints, push the creative person to greater depths.

His method seems to have been one of doing detailed drawings in pencil first and then inking in and erasing the pencil lines. He then builds up tonal contrast with multiple washes of browns and ochres and selectively colors areas by a similar build up of multiple transparent washes. His description of form is primarily through line therefore; but he uses tone and colour as very strong supporting players and very skillfully in order to draw the eye of the observer to those areas of the painting that he wants to be primary foci. This is done through: variation in contrast - lights next to dark attracts attention; variation in focus - sharp edges attract attention more than soft edges; and variation in colour - coloured areas attract attention when contrasted with other areas that describe form tonally, usually in sepias and greys. Accounts of his work talk about his understanding of 'new developments' in printing techniques and how he developed a way of working that allowed him to take adantage of thes. To the modern artists, who never needs to think about the capacity of modern technology to reproduce his work, of course, it would seems as though Rackham was working within constraints created by the limitations of printing. That being so, Rackham's work is another example of the maxim that one of my painting teachers use to say when forcing us to work within a limited palette: that very often being forced to work within narrow lateral constraints, push the creative person to greater depths.

There are many books now available of stories illustrated by him, and collections of his prints. They are a fascination for children and worthy of study by artist. The Amazon page for Rackham is here.

While I do admire his body of work in general I should point out that as I looked around for images to show, I noticed that some of his images of the female form, especially those from the Wagnerian there struck me as being tinged with an inappropriate eroticism. This is a shame. I didn't see it in his fairy tale illustrations, but it did make me think that as a parent I might want to look first before presenting them to my children.

Below: the first section are all from Jack the Giant Killer, including three uncoloured line drawings. Then one of his Wagnerian illustrations, A Midsummer Night's Dream and two from Peter Pan in Kensington.

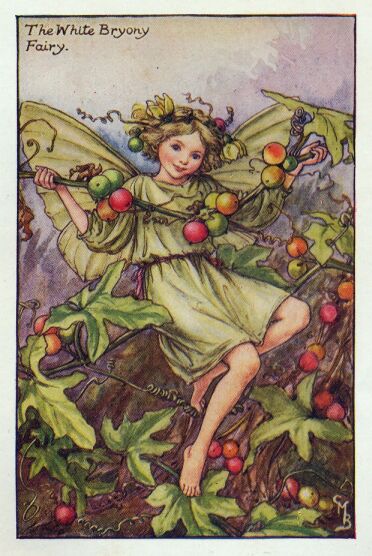

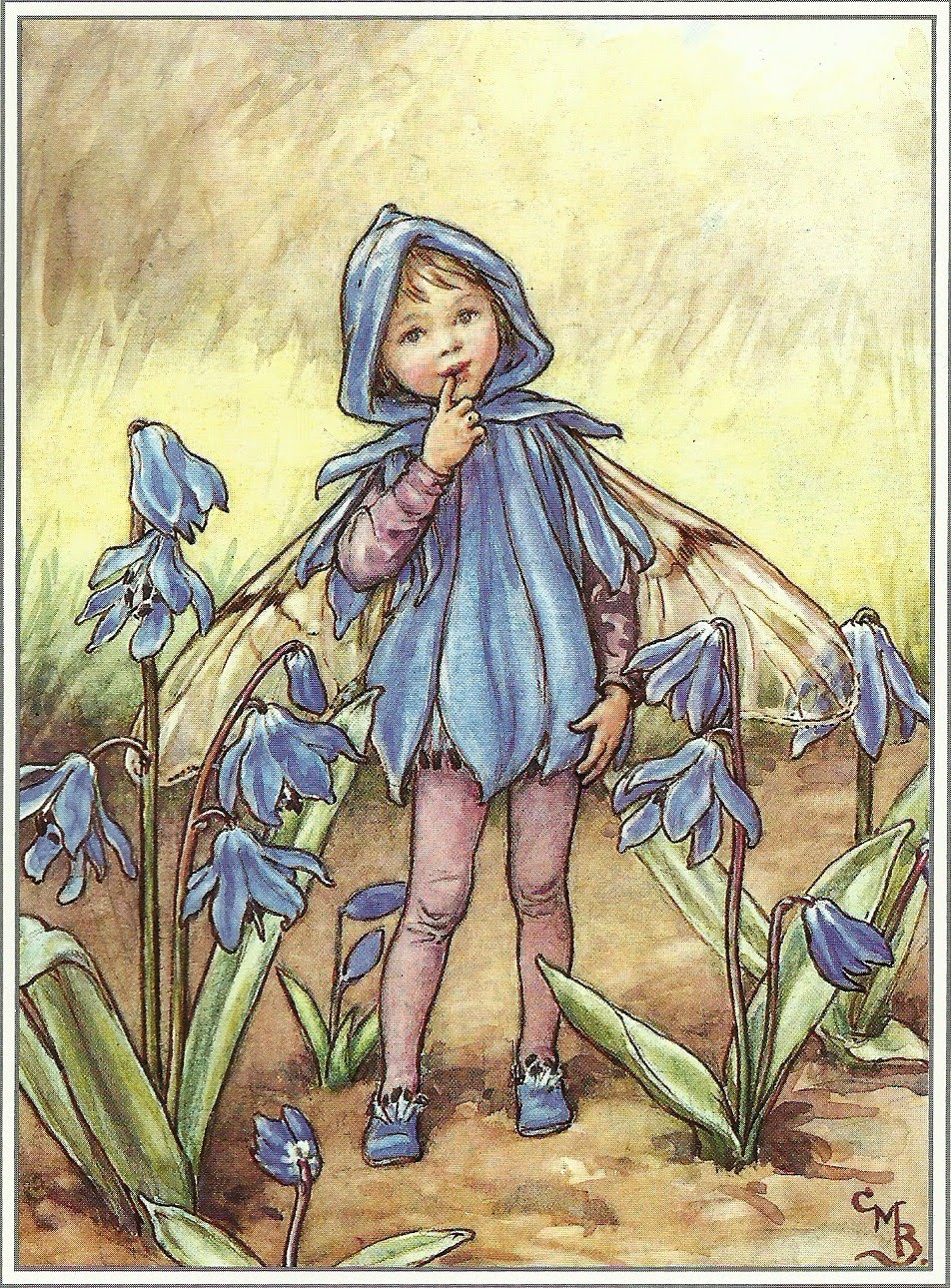

Cicely Mary Barker - Enchanting Illustrations for Children's Books

The first thirty years of 20th century seem to have been a golden period for illustration of children's books. We are all aware of the work of E. H. Shepherd, his illustrations the Winnie the Pooh books. But there are others that are well worth looking at. I will feature a couple in the next week or so. First Cicely Mary Barker (h/t Nancy Feeman!). She is in many ways the artist that Gertrude Jeckyll could have been...or perhaps Gertrude Jeckyll is the gardener that Cicely Barker could have been. Just like Jeckyll, Barker grew up in late-Victorian England and went to art school. Both had a love of English gardens, Barker deciding to paint them, and Jeckyll deciding to 'paint' flower beds. If you want to know more about her then there is a charming website Flower Faries with information about her, lots more illustrations and poems and books for sale at

The first thirty years of 20th century seem to have been a golden period for illustration of children's books. We are all aware of the work of E. H. Shepherd, his illustrations the Winnie the Pooh books. But there are others that are well worth looking at. I will feature a couple in the next week or so. First Cicely Mary Barker (h/t Nancy Feeman!). She is in many ways the artist that Gertrude Jeckyll could have been...or perhaps Gertrude Jeckyll is the gardener that Cicely Barker could have been. Just like Jeckyll, Barker grew up in late-Victorian England and went to art school. Both had a love of English gardens, Barker deciding to paint them, and Jeckyll deciding to 'paint' flower beds. If you want to know more about her then there is a charming website Flower Faries with information about her, lots more illustrations and poems and books for sale at

Barker produced a series of beautiful pen and wash paintings of 'flower fairies' for children's books. Each book would have a short poem and then an illustration. As Nancy Feeman, who brought her to my attention pointed out to me, these would be great for small children today and a great way to teach them to learn to recognise flowers in the garden. So here's the first lesson (which I pass on to you 5 minutes after I learnt it myself): the orchis is genis within the orchid family. Note that Ms. Barker is botanically correct in placing it among the 'family' of orchids.

Barker produced a series of beautiful pen and wash paintings of 'flower fairies' for children's books. Each book would have a short poem and then an illustration. As Nancy Feeman, who brought her to my attention pointed out to me, these would be great for small children today and a great way to teach them to learn to recognise flowers in the garden. So here's the first lesson (which I pass on to you 5 minutes after I learnt it myself): the orchis is genis within the orchid family. Note that Ms. Barker is botanically correct in placing it among the 'family' of orchids.

The Song of the Orchis Fairy

The families of orchids, they are the strangest clan, With sports and twists resembling a bee, or fly, or man; And some are in the hot house, and some in foreign lands, But Early Purple Orchis in English pasture stands.

He loves the grassy hill-top,

he breathes the April air;

He knows the baby rabbits,

he knows the Easter hare,

The nesting of the skylarks,

the bleat of lambkins too, The cowslips, and the rainbow,

the sunshine, and the dew.

The cowslips, and the rainbow,

the sunshine, and the dew.

O orchids of the hot-house,what miles away you are!

O flaming tropic orchids, how far, how very far!

All are exquisitely designed, drawn and painted. Stylistically she said that she loved the Pre-Raphaelites, but in contrast to them, she controls the focus and colour skilfully so that she often gives just enough of a suggestion of background to let us know what is there, with pale, diffuse articulation, but not so much that it detracts from the main points of attention. The Pre-Raphaelites, I feel, tend to overload the painting with colour and detail so that even the unimportant parts of the composition fight for our attention.

My only regret about these is that they seem to be aimed at girls and that's a shame because I would love to find a way for boys to learn about flower varieties as well. I don't think I would have enjoyed this when I was young but I can see that many would.

At the very top we have the Bluebell (scilla) fairy and Blackberry, Bryony, Apple Blossom, the cover of one of her books, Forget-me-not, Rose, Fuchsia and Winter Jasmine.

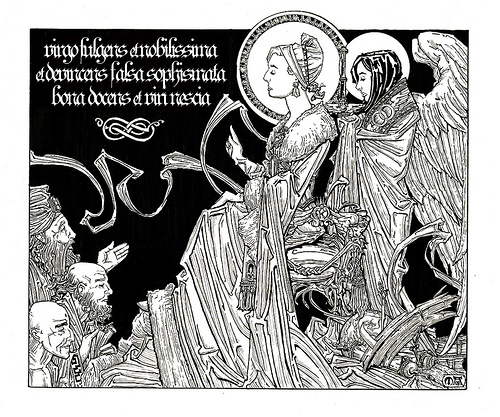

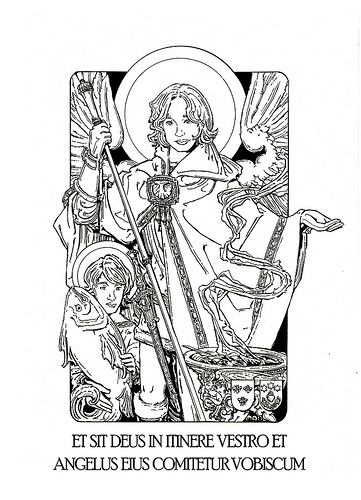

Matt Alderman, Illustrator!

Matt Alderman describes himself first as an architect (he trained at Notre Dame). He is a Catholic and a writes about sacred architecture for the New Liturgical Movement website. He also has his own blog about all matters Catholic and which is worth a visit, here. It is called the Shrine of the Holy Whapping (don’t ask me what the title means!).

He talks about his art as though its just a hobby on the side, but I find it interesting. He has, in my opinion, a natural sense of composition and his lines flow gracefully and rhythmically. He fills up the space without it being too cluttered. In this regard it reminds me of the English artist from the turn of the last century, Aubrey Beardsley. There is also something of another English artist, Arthur Rackham, about his work.

Matt Alderman describes himself first as an architect (he trained at Notre Dame). He is a Catholic and a writes about sacred architecture for the New Liturgical Movement website. He also has his own blog about all matters Catholic and which is worth a visit, here. It is called the Shrine of the Holy Whapping (don’t ask me what the title means!).

He talks about his art as though its just a hobby on the side, but I find it interesting. He has, in my opinion, a natural sense of composition and his lines flow gracefully and rhythmically. He fills up the space without it being too cluttered. In this regard it reminds me of the English artist from the turn of the last century, Aubrey Beardsley. There is also something of another English artist, Arthur Rackham, about his work.

Although I can say with certainty I like his work, I find it difficult to pigeonhole. Clearly, the subject matter reflects his faith, featuring lots of saints (and he has Catholic figures such as Dante there too). But the style is not one that which I would normally associate with sacred art (very different from Beardsley, for example who evokes a turn of the century decadence). I couldn’t see Matts's work in a church as liturgical art, for instance, or even an icon corner in the home as a focus for quiet prayer. It doesn’t make we want to pray. But it does draw me in and make me curious about the personality of the person depicted. These seem to me to be just the qualities that are needed in illustrations, which accompany text. I wonder, Matt, do you get any requests in this regard?

I should explain that I am not downgrading his work by describing it thus. Much of the quality artwork of the last century has come from illustrators. This point was made to me years ago when I was working as a lowly freelance sub-editor at the The Sunday Times in London. The art critic, Frank Whitford (who was a charming gentleman) always used to include reviews of illustrators’ art exhibitions in his weekly round-up. I can remember him reviewing a show of the work of E.H. Shepherd, for example, the creator of the images of the characters in the Winnie the Pooh books. I asked him why he included so many illustrator's shows. He said it was because illustrators were, in contrast to most artists nowadays, trained in the skills of drawing and painting and were directing their skills i conformity to an external purpose (rather than self-promotion). Consequently they very often produced the most interesting and original work around.

Above, from top: Dante; St Augustine.

Below, from top: St Catherine disputing with 50 pagans in Alexandria; St Peter Martyr; St John Kemble; Archangel Raphael.