There are many artists today working towards the reestablishment of the great naturalistic tradition of sacred art which was at its height in the 17th century, and this is to be encouraged. The artists coming out of the ateliers and studios that teach the traditional academic method who are adding greatly to this cause, and while there are some great painters of portrait and still life, I think that very often there is something wrong with the sacred art that they paint.

Someone recently asked me about this. He felt that they looked too individualised - like portraits of the person next door, which makes it difficult to identify the figure portrayed with the saint and the ideals that the saint represents. Is it possible that these modern examples of sacred art are too naturalistic he asked?

There are many artists today working towards the reestablishment of the great naturalistic tradition of sacred art which was at its height in the 17th century, and this is to be encouraged. The artists coming out of the ateliers and studios that teach the traditional academic method who are adding greatly to this cause, and while there are some great painters of portrait and still life, I think that very often there is something wrong with the sacred art that they paint.

Someone recently asked me about this. He felt that they looked too individualised - like portraits of the person next door, which makes it difficult to identify the figure portrayed with the saint and the ideals that the saint represents. Is it possible that these modern examples of sacred art are too naturalistic he asked?

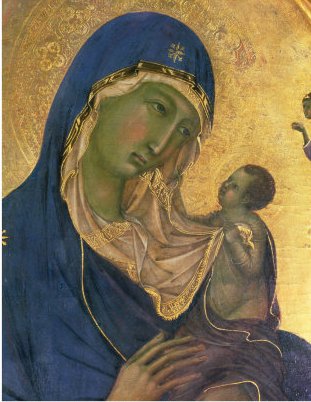

I think that the answer is yes. All Christian figurative art is a balance between naturalism – likeness to physical appearances – and abstraction. The latter is the stylization that enables the artist to reveal invisible truths by visible means. We are used to a high degree of stylization in icons, but are less aware that is there too, though more subtly employed, in naturalistic sacred art too. The problem with the modern sacred art is that most people who are trained academically today are trained to paint the human person as portrait painters. The balance between naturalism and idealism is differs - what is right for portraits, is not right for sacred art.

I think perhaps the seeds of this lie in the difference between 19th century academic art, which is a degraded from of the baroque of the 17th century, which is an authentic Christian tradition (although at first glace they look similar).

Most of the best artists today who are painting in the Western naturalistic tradition were trained in ateliers that teach the academic method as it was in the 19th century. Although the techniques learnt were the same in each case, the there were subtle differences in style between 19th century naturalism (sometimes called ‘Realism’) and 17th century baroque and this reflects a difference in the ethos that underlies each. The impetus for the formation of the baroque was the Counter-Reformation, which built on the work of the great artists of the High Renaissance, which preceded it. Although not all baroque art had an explicitly sacred purpose, stylistically it had its roots firmly in the liturgical art form.

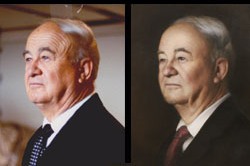

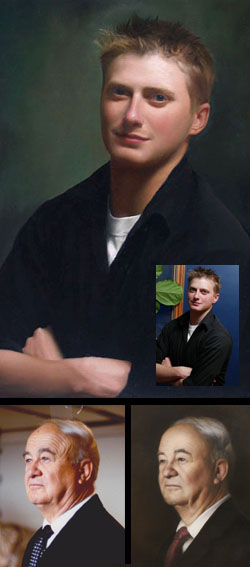

By the 19th century, the art of the teaching academies – ‘academic’ art - had become detached from its Christian ethos. So although there would be individual artists who were Catholic, it was no longer broadly accepted as a Catholic form. In this period, in regard to the painting of people, the main focus was portraiture, as this was where the money was to be made, rather than liturgical art. That is not to say that there was no sacred art all, but that portraiture became the driving force and so this is what formed the style. Characterising the difference in a nutshell: in the 17th century, you had artists whose training was directed to the painting of sacred art turning their hand to portraiture (and other mundane subjects); in the 19th century (and even more so today) you have the reverse – artists whose training is directed to portraiture (as well as still life and to a lesser degree landscape) turning their hand to sacred art.

Portrait painting, by its very nature, stresses the individual characteristic of the person. The Romantic period of the early 19th century added a new dimension. The artist was encouraged now to communicate in addition, their personal feelings about the person. This idea was not accepted by everybody immediately, but from this point we see a steady development of a sense of intimate involvement with the sitter. I do not object this to this in all cases -- I think it can work very well in portraiture. I love the portraits of the great 19th century artists (especially, for example, those of the American Boston school, which is the original source of the training I received in an atelier in Florence 100 years later). Although the unique aspects of the person are important in sacred art too, it must not be at the cost of communicating those aspects which are common to all of us. Those are the aspects of a saint that are of greatest interest to the rest of us sinners - for only the only aspects that we can emulate are those that are common to all of us.

We are made in the image and likeness of God. We are in the likeness of God in those aspects that are subject to the Fall and so can be improved with God's grace. These are the very aspects that saints reveal to us as an ideal and which are presented to us as an inspiration to do the same. In this they point to the Christ-like qualities that we should all aim to imitate. It is this idealized aspect that, in my opinion, is missing from the academic art both of the 19th century and it is even more pronounced in its current manifestation. The result in the context of sacred art is very often a painting that communicates an over-familiarity with the individual. It looks like a set from a Victorian melodrama – with a friend or relative dressed up as Our Lady, rather than Our Lady herself.

Contrast also William Bougeureau’s Virgin and Lamb [above], painted at the turn of the 20th century with Raphael’s tondo the Alba Madonna of 1511 [below].

Raphael deliberately idealized his work, to evoke the heavenly ideal, by basing it on the idealized features of ancient Greek art. Bougeureau’s Madonna, on the other hand, is tinged with a sentimentality that is, in my opinion, inappropriate for the subject which result, I believe, from this over intimate rendering of the person. However, looking another piece of work by the same artist, but this time a portrait, we see a work of both great vigour and beauty.

His style is appropriate here, I feel.

As another piece that has this staged-pose look, I would cite also Jules Bastien-Lapage's St Joan [below].

Bastien-Lepage was famous for painting rural scenes of peasants. Although rendered with dazzling skill (perhaps beyond the level of any artist I know of today) it still has the look of a model, dressed up in peasant garb rather than something that points to the saint. I would struggle to pray in front of this in a church. It is just too present and immediate. And, like Bougeureau, for all the weaknesses of this as a piece of devotional art, Bastien-Lepage's portraits are, in my opinion, splendid.

In naturalistic art it is appropriate to communicate strongly the emotions of the subject painted (in contrast with icons for example, where it is less true). We read emotions of people by looking at their faces and by gesture. It occurs to me that perhaps one of the reasons that the baroque stresses gesture so strongly is that it provides a way of communicating emotion without requiring the observer to focus there attention so strongly on the face and so hightening too much the uniqueness of the person.

So assuming we accept the analysis, how can we avoid it this problem today? I think that the answer lies in the training.

The style within a tradition has always been transmitted by the Masters we study. So, artists seeking to produce should study and copy, in the spirit of understanding, the works of the Masters of liturgical art they admire. Although I love the work of Raphael, and there are many aspects of his work I love to be able to emulate, I would not want to do so in this particular regard – if anything he swings in the opposite direction and the idealization is overemphasized for my tastes. I would go first for the great artists of baroque naturalism, for example, Georges de la Tour [below], Velazquez, Ribera and Zurbaran [below the de la Tours].

All of these artists, (the examples shown are de la Tour's St Joseph and Zurbaran's St Francis) presented saints with a balance of the individuality and idealisation that strikes the right balance. If there was a more recent artist whose sacred art succeeds, I would suggest the 20th century Italian, Pietro Annigoni. I saw his St Joseph [below] hanging in a church in Florence alongside baroque masters and despite its modern appearance in many other respects, it did not look out of place at all.

There is another aspect that could be introduced into the training of all artists that wasn’t present in the 17th century, but which nevertheless might help. Artists cannot help but be influenced by the art we have seen and we live in time in which we are bombarded by photographic imagery in all its manifestations. As a result the subtleties of the balance of the particular and the ideal that we are discussing are not easily reproduced even if we want to. I think that some exposure to a form of painting in which the idealized form is much more obvious and is clearly linked to theology would be beneficial. I would always recommend, therefore, that even an artist who eventually wants to specialize in the Western naturalistic tradition include some iconography in their foundational training. The actual experience of creating icons is more likely to impress these values upon the souls of artists so that intuitively they will include them in their own work.