A book that explains why the American ideal of ordered liberty is consistent with a holistic view of human flourishing that is described in Catholic social teaching:

Tea Party Catholic: the Catholic Case for Limited Government, a Free Economy and Human Flourishing, by Samuel Gregg (www.teapartycatholic.com)

A book that explains why the American ideal of ordered liberty is consistent with a holistic view of human flourishing that is described in Catholic social teaching:

Tea Party Catholic: the Catholic Case for Limited Government, a Free Economy and Human Flourishing, by Samuel Gregg (www.teapartycatholic.com)

If you want to know what this book is about, at least read the whole of the front cover. If you got no further than Tea Party Catholic, it would be easy to mistake it as a piece of current affairs and contemporary social commentary. This is much more than that.

Although not unconnected with the values of the modern Tea Party movement that the title evokes, it is more a reference to the original Boston Tea Party and describes the influence of the sole Catholic signatory to the Declaration of Independence, Charles Carroll. Through papal writings especially those of Leo XIII, John Paul II and Benedict XVI he demonstrates that the free market, liberty, limited government and other ideas that characterize the American conservative mindset are consistent with Catholic teaching on the human person, freedom and capitalism. I suggest that it is important enough that it should be standard reading in the general education of all students - not just Catholics and not just Americans - for years to come.

For Catholics it is a great introduction to the basic principles of Catholic social teaching, freedom and the human person and the nature of a society in which the human person can flourish.

For American Catholics and especially those who doubt that the American constitution and characteristic American values are consistent with the Catholic worldview, he demonstrates the harmony between the two visions of society. I have often felt that some are too quick seize upon the fact that each defines the terms 'freedom' and describes the human person differently and use it as a reason to dismiss the principles upon which America is founded as contrary to Catholic thinking. As Gregg explains although some of the language of the Founding Fathers is characterized by that of Enlightenment thinking - the principles that they are describing can be shown to be consistent the Catholic thought, developments in CST which occurred much later.

For American Catholics and especially those who doubt that the American constitution and characteristic American values are consistent with the Catholic worldview, he demonstrates the harmony between the two visions of society. I have often felt that some are too quick seize upon the fact that each defines the terms 'freedom' and describes the human person differently and use it as a reason to dismiss the principles upon which America is founded as contrary to Catholic thinking. As Gregg explains although some of the language of the Founding Fathers is characterized by that of Enlightenment thinking - the principles that they are describing can be shown to be consistent the Catholic thought, developments in CST which occurred much later.

If you could get any of them to read it, it would be an eye-opener to the large numbers of Europeans who are like I used to be: anti-American, anti-capitalist, anti-business and pro-socialist; who are taught to believe that the interests of business are fundamentally opposed to the good of society as a whole and the well being of the poor in particular; and have no knowledge of the principles upon which America was founded or any sense that they were even worthy of investigation.

This book will counter these prejudices on two fronts.

First, Gregg clearly articulates how Catholic social teaching describes the principles by which society can be ordered so that it is prosperous and the human person can flourish. Furthermore, CST is quite specific that this cannot include socialism and that a society that favors markets, the free economy, business and entrepreneurs, and is built on a culture of faith, morality and trust is the one that offers the greatest hope for all people, especially the poor.

Second, his description of the meaning of traditional American values demonstrates, I believe, that America offers hope to the West in a time of crisis. The cultural foundation upon which so much that is good in the modern age and upon which the West is founded is more than Christian, it is Catholic. This being so, these American values which are so smugly rejected by many - especially the university educated - in fact represent a beacon of light in the West that is otherwise throwing away so much of its Christian heritage. If this is not stopped we are on a path to disaster.

Second, his description of the meaning of traditional American values demonstrates, I believe, that America offers hope to the West in a time of crisis. The cultural foundation upon which so much that is good in the modern age and upon which the West is founded is more than Christian, it is Catholic. This being so, these American values which are so smugly rejected by many - especially the university educated - in fact represent a beacon of light in the West that is otherwise throwing away so much of its Christian heritage. If this is not stopped we are on a path to disaster.

This last point could be noted as well, I think by many Americans who are, as I was surprised and somewhat dismayed to discover when I moved here, ashamed of their own culture and starry-eyed about Europe. Perhaps because I am English, it seems to bring this side out of them and they will quickly find a reason to apologize for their own culture and praise that of Europe, which they view as inherently superior. They identify European culture, I am guessing, with that which produced the beautiful buildings and art they see in European cities and do not seem to realize that modern European culture is far removed from the one that created these wonders.

If you want hope for the future it is not to Europe we must look, but to that part of American society that still espouses its traditional values and therefore, whether they know it or not, Catholic Social Teaching. That is not to say the American culture is perfect (although it is far better than most of these negative Americans and Europeans give it credit for). Rather it is that American society still has far more of what is necessary for such a transformation. From this starting point there is still, in my opinion, the possibility of infusing it with more so that it can be culture of greater beauty and in which the human person can flourish. My conviction about this arises not from a deep knowledge of the history of the founding of the United States, of which still am no expert, but from personal observations of American society. But I see support for this view in Gregg's book.

As Gregg put it it: 'Subsidiarity tells us that the primary responsibility for limiting the temptations associated with the affluence generated by market economics lies with non-state organizations, especially families and churches. Parents are usually better placed than government officials to teach their children how to value material goods, to use mass media, and apply their minds critically to what they see and hear so that they can make clear judgments about what they are being told in advertising. The long-term goal is to root free markets in a moral culture that enables us live in societies akin to the Florence of the High Middle Ages and the Renaissance; communities in which widespread commerce, banking and trade went hand in hand with the literature of Dante and the art of Michelangelo.'

As Gregg put it it: 'Subsidiarity tells us that the primary responsibility for limiting the temptations associated with the affluence generated by market economics lies with non-state organizations, especially families and churches. Parents are usually better placed than government officials to teach their children how to value material goods, to use mass media, and apply their minds critically to what they see and hear so that they can make clear judgments about what they are being told in advertising. The long-term goal is to root free markets in a moral culture that enables us live in societies akin to the Florence of the High Middle Ages and the Renaissance; communities in which widespread commerce, banking and trade went hand in hand with the literature of Dante and the art of Michelangelo.'

Well I might say Duccio or Giotto rather than Michelangelo but I don't want to quibble! The point is very well made.

To read more and to buy the book go to www.teapartycatholic.com

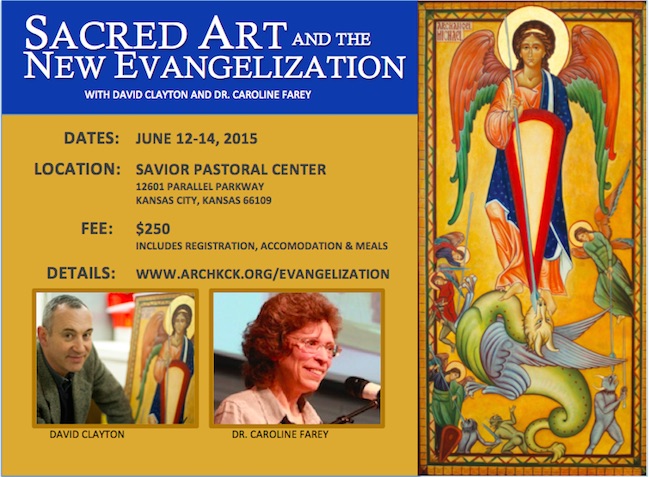

Sam Gregg will be teaching at Acton University - the annual conference of the Acton Institute in Grand Rapids, Michigan, June 16-19 which is open to everyone, and thoroughly recommended to all.

Don't forget the Way of Beauty online courses www.Pontifex.University (go to the Catalog) for college credit, for continuing ed. units, or for audit. A formation through an encounter with a cultural heritage - for artists, architects, priests and seminarians, and all interested in contributing to the 'new epiphany of beauty'.

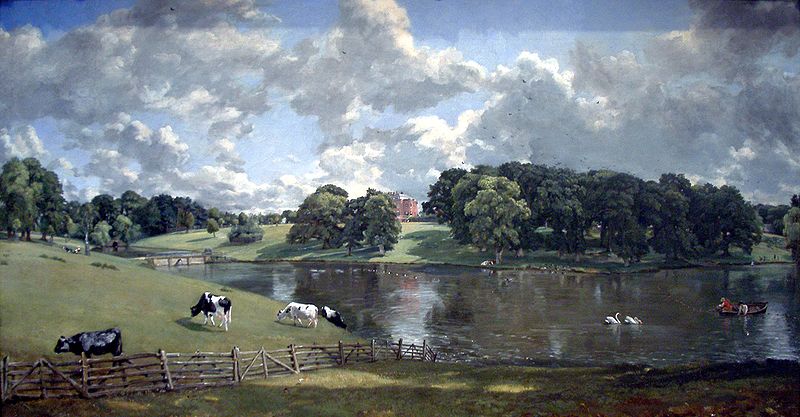

I can only marvel at the work of French artist Corot (1796-1875). He follows that baroque format of variation in focus rendering much of out blurred and out of focus. In this respect some might liken him to the Impressionists who followed him. But to my eye he differs in that he retains the sense of a sharp focus. There are enough edges and sharp contrasts for give the roving eye places to rest comfortably. Corot was part of movement of landscape painters, called the 'Barbizon' (after a village near Fontainbleau Forest where they gathered). They consciously modelled their work on John Constable's landscapes and ideas. Constable's work had been popular in France and he had exhibited his work there. I think that my comments on his approach are, not surprisingly, similar to those I made in regard to Constable. For example, he tends to work tone into the natural colour of what is being painted, greens, for example, of the landscape. However, Corot seems to have developed further what Constable did and is perhaps even more masterly in his ability to combine all these competing considerations in a unified beautiful image. His rendering of foliage and especially the appearance of trunks and branches within the form of the tree or shrub is immensely skilfull. I would refer those who haven't read them to my other articles on baroque landscapes in previous weeks. Beyond the general comments about landscape I have very little to say other than just enjoy the beauty of his work.

Baroque Landscape

I can only marvel at the work of French artist Corot (1796-1875). He follows that baroque format of variation in focus rendering much of out blurred and out of focus. In this respect some might liken him to the Impressionists who followed him. But to my eye he differs in that he retains the sense of a sharp focus. There are enough edges and sharp contrasts for give the roving eye places to rest comfortably. Corot was part of movement of landscape painters, called the 'Barbizon' (after a village near Fontainbleau Forest where they gathered). They consciously modelled their work on John Constable's landscapes and ideas. Constable's work had been popular in France and he had exhibited his work there. I think that my comments on his approach are, not surprisingly, similar to those I made in regard to Constable. For example, he tends to work tone into the natural colour of what is being painted, greens, for example, of the landscape. However, Corot seems to have developed further what Constable did and is perhaps even more masterly in his ability to combine all these competing considerations in a unified beautiful image. His rendering of foliage and especially the appearance of trunks and branches within the form of the tree or shrub is immensely skilfull. I would refer those who haven't read them to my other articles on baroque landscapes in previous weeks. Beyond the general comments about landscape I have very little to say other than just enjoy the beauty of his work.

Baroque Landscape