https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NNvGNdv_dp0

The Pocket Oratory - a stocking filler for every holy season

Nanci Keatley has just sent me photographs of these updated versions of her pocket oratory. They are handmade and are a great portable aid to contemplative prayer as they engage the sight and the imagination and directs our thoughts to heavenly things. I have one and use it daily.

Some will remember my extended essay on the connection between the New Evangelization and the Domestic Church and how the core imagery is chosen specifically to open us up to the supernatural. For those who did not read it the first time you can read it here. The three key images are the suffering Christ, Christ glorified and Our Lady.

Now at any moment you can use this visual aid for prayer and pray the office (if you have your smartphone); or personal prayer (if you don't). When folded they are about three inches by four inches. They fit easily into the inside pocket of a jacket.

If you are interested in getting hold of one, Nanci's email is fencing_mama@comcast.net

Denis McNamara - on church architecture and the restoration of images.

This is the second video within the series that focusses on sacred images particularly. In this he argues for a resoration of sacred images in churches which respects a hierarchy of imagery. Describing first the reasons for the iconoclasm of period after Vatican II (with more charity towards those responsible than I could muster) he then indicates some principles by which we can restore imagery so that we don't just repeat the problems that existed before the Council. This means giving the altar greatest prominence followed by authentically liturgical art. This is art that depicts the heavenly liturgy in a form that is appropriate to the high purpose. He acknowledges that there is a place for devotional images in church provided they do not distract from the liturgical function.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CbbArAwwuYU

A Call to Men in Parishes from Cardinal Burke - Join the Holy League

A friend, Tom, in New Hampshire contacted me to tell me that he and another are establishing a Holy League in response to this call from Cardinal Burke.

This intended to create a network of parish based men's groups that meet monthly in a structured Holy Hour. The Holy League was first formed as part of the call to holiness and fortitute that occurred when Europe was under threat from Islamic forces and prior to the battle of Lepanto in 1571. The aim is to reestablish this in every Catholic parish.

The website tells us that the Holy League:

- Provides a Holy Hour format which incorporates: Eucharistic adoration, prayer, short spiritual reflections, the availability of the Sacrament of Confession, Benediction and fraternity;

- Encourages consecration to the Most Sacred Heart of Jesus, the Immaculate Heart of Mary, and the Purest Heart of Joseph;

- Promotes the Precepts and Sacraments of the Church; especially through devotion to the Most Blessed Sacrament and the praying of the Most Holy Rosary;

- Creates a unified front, made up of members of the Church Militant, for spiritual combat.

In addition to this, Tom told me that they intend to sing Compline during this hour as well. This sounds great to me!

You can read more about it here and below see a short description of it by the Cardinal.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pp764vr35wk&feature=youtu.be

Denis McNamara on Church Architecture, part 7 - Sacred Images

In this one he focusses on sacred images. He describes how sacred images are a necessary part of the environment for the worship of God because they manifest those aspects of the liturgy that are present but not ordinarily visible. So they are there to give us a sense of the angels and saints in heaven participating in the heavenly liturgy.

In this video, the stylistic features of art that he describes are those of the iconographic tradition which portrays man fully redeemed. One point that he doesn't address in this short presentation is the how the other authentic liturgical traditions, the gothic and the baroque, fullfill this function. I would argue that they do exactly what the iconographic styles does, but in a subtly different way. They are stylistically different and do not reveal man fully redeemed, but rather justified and at various stages on the path to heaven. But it is by revealing the path they direct our attention, via the imagination, to the destination point of that path, which is our heavenly destiny and so fulfulling their liturgical function. (If you are interested in a fuller discussion of this last point I direct you to section three of my book, the Way of Beauty.)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mxjgAP495-I

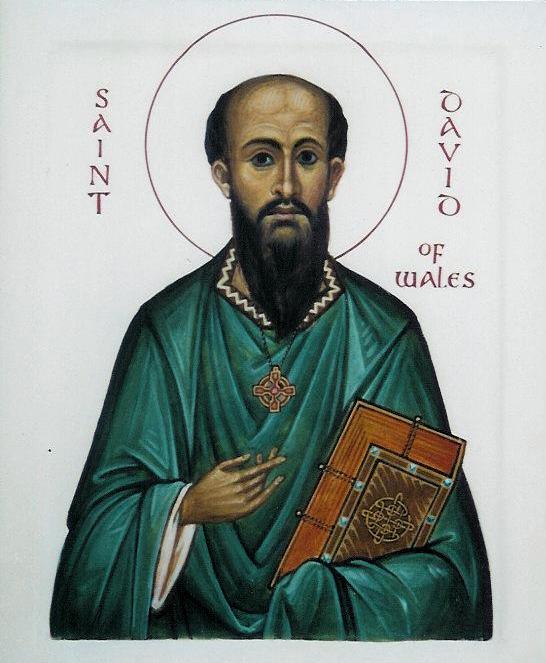

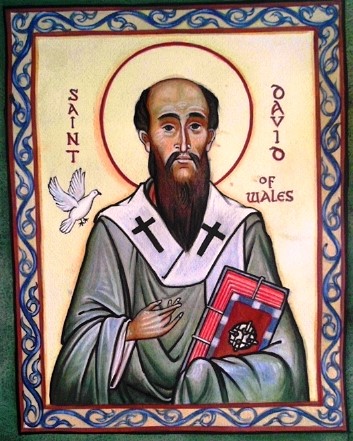

New icon, St David of Wales

This is painted in egg tempera on watercolour paper. I have based it, on another of Aidan Hart's icons of early British saints. He has done a series of similar ones to this, but I don't know if this is his own prototype or if he drew inspiration from another source. Regardless, I love his work and very often look to his corpus first when considering how to approach a subject.

This is in my icon corner at home and I noticed this morning that his right eyelid, the left as you look at it, is drooping slightly. I'll have to modify it.

This is one of the drawbacks of painting for you own prayer, you can be distracted by your own errors! Here is Aidan's:

Denis McNamara on architecture, part 6: columns

I found this one particularly fascinating.

Denis describes here how columns are a vital part of the design of the church building which is meant to be the sacramental image of the Church, the mystical body of Christ. Historically the building was so clearly identified as an image of the Church, that this is why it came to be called a 'church'.

The columns represent important people within the Church who, metaphorically, support it. Most importantly it would be the 12 apostles. Prior to the Christian era the columns represented the 12 tribes of Isreal in Jewish architecture. Even within the classical, pre-Christian tradition, columns were identified with people and different designs were ascribed to men, women and young girls. With the tradition present in both the Jewish and classical traditions that preceeded them, we can see why it made great sense, for the early Christians to incorporate the same symbolism into the design of their churches.

It is because they are symbolic images of people that there are particular aspects of design on the columns, again incorporated into the tradition, and they should not just be created as straight vertical lines that are pure structural support - as a modern architect might wish to do. It does not mean that every column should necessarily correspond precisely to the Doric, Corinthian and Ionic columns of classical architecture, but it does point to importance of columns of some form as symbolic images of people, as decoration that visibly performs a structural purpose.

The question one might have after considering this is, even if we acknowledge that properly formed columns are right for a church building, is do we need to have them in secular buildings as well? What about libraries, town halls, houses, theatres, and so on?

I would say again that the church should be the symbolic heart of the community. Therefore, just as all human activity is formed by and leads us to the worship of God, so the design of all buildings whatever their purpose should be derived from and point to what should be the focal point within the town plan, the church and so we ought to see columns in secular buildings too. All of this should be modified so that each building is appropriate to its particular purpose: a government building would have a design that is mre directly corresonding to a church, I would suggest, than a cow shed or a public convenience.

https://youtu.be/CIw_zw-QCJk

Titian the trailblazer - showing us how to balance naturalism and symbolism

Titian is one of the greats of Western art. He lived from about 1480 to 1576, in Venice, and was active almost right to the end of his life. He began painting in the period of the High Renaissance and when he died was in the latter part of the 16th century which was characterized by individual artistic styles collectively called 'mannerism'. Titian's style, though individual to him when he established it, was highly influential and much of what characterized the baroque tradition of the 17th century was derived from his work. In some ways he can be considered one of the pioneers of the baroque style that dominated in the 17th century. This is important because the baroque is the one artistic traditions that Pope Benedict describes, in his book, the Spirit of the Liturgy, as being an authentic liturgical tradition.

Some people may be surprised, as I was, to discover that the High Renaissance (the style of Leonardo, Michelangelo and Raphael from about 1490 to 1525) is not considered fully and authentically liturgical (ie right for the Catholic liturgy). This is not to say that there are not individual works of art from these great artists that might be appropriate, but that it was not yet a coherent tradition in which a theology of form had been fully worked out, as was later to happen for the baroque. Pope Benedict argues that for the most part it was too strongly influenced by the pagan art of classical Greece and Rome and reveals the self-obsessed negative aspects of classical in a way that is not fully Christian.

Titian is one of the greats of Western art. He lived from about 1480 to 1576, in Venice, and was active almost right to the end of his life. He began painting in the period of the High Renaissance and when he died was in the latter part of the 16th century which was characterized by individual artistic styles collectively called 'mannerism'. Titian's style, though individual to him when he established it, was highly influential and much of what characterized the baroque tradition of the 17th century was derived from his work. In some ways he can be considered one of the pioneers of the baroque style that dominated in the 17th century. This is important because the baroque is the one artistic traditions that Pope Benedict describes, in his book, the Spirit of the Liturgy, as being an authentic liturgical tradition.

Some people may be surprised, as I was, to discover that the High Renaissance (the style of Leonardo, Michelangelo and Raphael from about 1490 to 1525) is not considered fully and authentically liturgical (ie right for the Catholic liturgy). This is not to say that there are not individual works of art from these great artists that might be appropriate, but that it was not yet a coherent tradition in which a theology of form had been fully worked out, as was later to happen for the baroque. Pope Benedict argues that for the most part it was too strongly influenced by the pagan art of classical Greece and Rome and reveals the self-obsessed negative aspects of classical in a way that is not fully Christian.

As a young man Titian trained during the High Renaissance and the influence of this can be seen in this early painting of his, the Enthronement of St Mark. At the feet of St Mark are Ss Cosmas and Damien on the left, and St Sebastien and St Roch on the right. This was painted in 1510 and one could be forgiven for thinking it was painted by Raphael. Notice how sharply defined all the figures and all the details are, even the floor tiles.

If you compare this with the following paintings we see how his work changed as he got older. The first is Cain and Abel painted in 1543; and the second is the entombment of Christ, painted in 1558. In the latter Joseph of Arimathea, Nicodemus and the Virgin Mary take Christ in the tomb watched by Mary Magdalene and Saint John the Evangelist.

We can see how, in contrast to the first painted how diffuse and lacking in color much each painting is. The edges are blurred in many places and only certain areas have bright or naturalistic color. Those areas of primary focus are painted with sharper edges and with bright colors. This is done to draw our attention to the important part of the composition. He cannot apply bright color to the figure of Christ but notice how he uses the bright colors from the clothes of the three figures who are carrying him to frame his figure. In contrast the two figures in the background are depleted of color and detail. He wants us to be aware of them, but not in such a way that they detract from the most important figure. He uses the white cloth draped over the tomb in the same way, making sure that the sharpest contrast in tone, light to dark is between this and the shadow of the tomb. They eye is naturally drawn to those areas where dark and light meet and this is how Titian draws our gaze onto Christ.

It is suggested that this looseness of style in Titian's later works occured because as his eyesight declined, he was unable to paint as precisely as he had done as a young man. This may well have been what forced him to work differently, but if so, all I can say is, my, how he accomodated his handicap so as to create something greater as a result!

If we go forward now to early 17th century Rome, it is the artist Caravaggio who is often credited with creating the characteristic visual vocabulary of exaggerated light and dark of the baroque style. We have seen deep shadow and bright light before this time, but Caravaggio exaggerated it and embued it with spiritual meaning in a new way. The shadow represents the presence of evil, sin, and suffering in this fallen world; and it is contrasted with the light which represents the Light, Christ, who offers Christian hope that transcends such suffering.

This visual vocabulary of light and dark can be seen in the painting above. Notice how it is so pronounced that in this example we do not see any background landscape; all apart from the figures is bathed in shadow. One thing that Caragaggio does retain from the visual style of the High Renaissance is that generally his edges are sharp and well defined, even if partially obscured by shadow. Other artists looked at this and while adopting Caravaggio's language of light and dark, incorporated also the controlled blurring edges that characterized Titian. What we think of as authentic baroque art is a hybrid of the two.

Look at the following painting by the Flemish artist, Van Dyck, St Francis in meditation, painted in 1632:

We can see how much he has taken from Titian in this painting. Van Dyck trained under Rubens. As a young man in 1600, Rubens travelled to Italy where he lived for eight years. His travels took him to Venice (where he saw the work of Titian), Florence and Rome (where much of Caravaggio's work was). He was influenced strongly by both and passed on these influences to his star pupil.

New icon: St Edna, Abbess of Whitby

This recently painted icon is St Edna, who succeeded St Hilda as the Abbess of Whitby in the 7th century. I based this icon a series painted by Aidan Hart of early British saints, including one of St Hilda herself. These seem to me, in turn, to be inspired by an icon of St Theodora from Mt Sinai in Egypt. This is for my domestic church.

'Decoration' and 'Ornament' - Denis McNamara of Architecture 5

Why both are necessary for the beauty of the building

Here is the fifth in the series of short videos by Denis McNamara. Denis is on the faculty of the Liturgical Institute, Mundelein; and his book is Catholic Church Architecture and the Spirit of the Liturgy. Scroll to the bottom if you want to go straight to the video!

Here he distinguishes between two similar, but crucially different ways in which the building is made beautiful - 'decoration' and 'ornament'. The two words are interchangeable in common parlance, he is using them here as technical terms that been developed by architects in order to be able to describe two complementary aspects of a building that are necessary for its beauty.

In the way Denis describes them decoration is a 'poetic', that is beautifully applied adornment that reveals the structural elements of the building. This is to be distinguished from the modern architect's desire to show the structural elements literally, almost brutally, without regard for beauty. The columns used in neo-classical architecture, for example are designed to reveal beautifully their load bearing function.

The church above is a neo-classical design in Poland, while the building below is an 18th century civic building from York in England that clearly points to and is derived from the church architecture.

As we will see, while one would not be surprised to see similar decoration on the two buildings. We would expect to see different ornament. That is because ornament is an enrichment that tells you the purpose of the building. A cross on a steeple, for example, is ornament as it reveals the buildings theological purpose. The cross of St George (the patron saint of England) on the York building tells Englishmen that this is a civic building...although ironically, this is also the Resurrection flag (although as an Englishman I didn't know this until I converted!).

Decoration and ornament are both necessary for a beautiful building because they contribute to the form in such a way that it tells us what this building is. Beauty, remember, is the radiance of being: a property of something that communicates to the observer what he is looking at.

In the flying buttresses of gothic architecture, it occurs to me, this distinction between decorative and literal in structural elements almost seems to disappear. Architects please feel free to contradict me if I am mistaken, but these are fully structural and literal in that sense, but they are also built in harmonious proportion. Might this represent the highest ideal for the architecture?

Anyway, here is the link to Denis's talk:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hEi0aqNFpVw

How do we paint disfigurement and bodily imperfections in saints?

Blessed Margaret of Castello is the patron saint of unwanted and disabled children. Born in 14th century Italy, she was disfigured and neglected from birth by her wealthy parents. She was taken in by Dominican nuns when she was sixteen and became a third order Dominican. Her story is both harrowing and inspiring: harrowing because of the suffering and cruelty she experienced; and inspiring because of her joy in life, which arose from her faith and transcended that suffering. Here is an account of her life from the website of the Dominican sisters at Nashville. As I read this story it occured to me that if this had been today and her parents had had access sonogram prior to her birth she would surely have become another abortion statistic.

A friend of mine, Gina Switzer, told me that she had been commissioned to paint her and we were discussing how artists might represent human disfigurement in saints so that they retain the dignity of the human person. So this week, I thought I'd write about this - for those who are looking for the continuation of the series, we'll come back to the series of architecture videos next week.

The first point is that it is not immediately clear that human imperfections should be portrayed in holy images. One might assume that these are absent in heaven and so to the degree that we show the redeemed person, argue that they should not be there at all. I was reminded that Denis McNamara told me recently that when they were designing the stained glass windows for the new John Paul II chapel at Mundelein, they thought about this and deliberately left out St Maximilian Kolbe's spectacles for just this reason.

The counter to this is that in order to make an image worthy of veneration, according to the theology of holy images established by St Theodore the Studite in the 9th century, two things need to be present: first the name should be written on the image; and second it should portray the essential visual characteristics of the saint. This last criterion refers to those aspects of the saint that together give the person his unique identity. This can include a physical likeness, although a rigid application of physical likeness is not appropriate - a holy image is not a portrait. We are thinking here of those things that characterize the person and his story, for example, St Paul's baldness, the tongs containing hot coal for Isaias. With this in mind, to use the example of the JPII chapel again, Denis told me that for Blessed Teresa of Calcutta they did want to show her deformed feet because it symbolized her charity - this disfigurment arose because she always chose the worst shoes for herself from those donated to the order. We thought that for St Margaret, in this age of the culture of death, the portrayal of her joyful but with her physical imperfections would be particularly important.

One ideas was to look for inspiration at the dwarfs painted by Velazquez from the court of Philip IV of Spain, who have great dignity and bearing. This idea was rejected, firstly because they can also have an imappropriate haughtiness about them which would have to be changed. And second, because to incorporate all of these considerations into a naturalistic style and be able to pull it off would be very difficult indeed - it might almost require a Velazquez to do it. Even in naturalistic styles there should always be a degree of symbilism (or idealism) and this is notoriously difficult for contemporary Catholic artists to get right even for easier subjects. (Below you see his portrait of Sebastien de Morro.)

In the light of all these considerations I thought that I would probably paint an image in a gothic or iconographic style in which her natural physical characteristics were shown, retained but nevertheless redeemed in some way. The first thing I always do is, as I was taught, look first at existing images and if I can find one that is appropriate, just copy it. The aim to change as little as possible. If there is no perfect image to copy then I look at other images from which I can use the particular characteristics that appear to be missing from my desired image and patch them together into a single image. Only if I can find nothing that has already been painted do I attempt something original. I create drawings made from observation of nature and onto those I impose the stylistic form of the tradition that I am working in.

I found this picture of this sculpture of St Margaret.

I thought that a painting in egg tempera based upon this would work. A change I would make, I though, would be to change the face to one that is more joyful. I like the ones that I see in a series of Aidan Hart's icons, such as St Winifride or St Hilda of Whitby or St Melangell, which look to me as though they are based on an ancient icon of St Theodosia which is at Mt Sinai. You can see images of each below. One thing that I would do is close her eyes to indicate St Margaret's blindness:

Denis McNamara of Architecture, part 4: the Classical Tradition

And no, this does not mean that every building has to look like a Roman temple.

Here is the fourth in the series of short videos by Denis McNamara. Denis is on the faculty of the Liturgical Institute, Mundelein; and his book is Catholic Church Architecture and the Spirit of the Liturgy.

Before I sat in on some of his lectures this summer, I had been aware of Denis's emphasis on the classical tradition in architecture. I have to admit, I did have half a suspicion that his ideal was a world of faux Roman temples - all domes and Doric columns.

As I found out, and as you can see in the video, he does not mean this at all - although it does include what most of us think of as classical style. He describes classical architecture as any style that is created out of a respect for tradition and which participates in order of nature that 'reveals the mind of God'. This includes, for example, gothic architecture.

Furthermore, he says that a respect for tradition does not mean that we look back, rather it provides a set of principles that will guide us as we go forward employing forms that might echo the past closely, or on the other hand might have styles that are previously unimagined. The potential range of styles is limitless.

Rather than painting a picture of people walking backwards reluctantly into the future wishing they could head for the past, he is giving us one which is closer to the crew of a beautiful sloop that looks forward in optimism as it sails into the rising sun in the East, with tradition firmly at the tiller.

His reference to the mind of God is reminiscent of language used by Pope Benedict XVI, the Spirit of the Liturgy in which he describes how the numerical description of the patterns of the cosmos give us a glimpse into the mind of the Creator. Even the beauty of this world as it is now, fallen, does not reveal the divine beauty fully, for it is a fallen world. The question the good architect asks himself when designing a building is not so much, how can I reflect the beauty of the cosmos as it is, but rather, how can I reflect the beauty of the cosmos as it is meant to be? For me a critical point is that if we want beauty we cannot escape this question, for there is no order outside the divine order, only disorder and ugliness. Any building, or for that matter any aspect of the culture that does not look forward to the heavenly ideal

Onwards and Eastwards!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MDpg_ChcgfI

Pictures from the Way of Beauty explained: Attingham House, Shropshire

A perfect exemplar of traditional harmonious proportion. And how modern research supports the traditional consensus for what is beautiful.

This is a picture that is only referred to in the book. For various reasons we were unable to include it in the book. I visited Attingham park in Shropshire in the Midlands area of England with my icon painting teacher Aidan Hart. We went primarily to enjoy the extensive grounds which are beautifully landscaped. I always thought that it was made in the 17th century, but in fact I notice now that it was build in the late 18th century.

It is a National Trust property, which means that it is owned by the state and considered a place of outstanding interest and beauty. When I was there I noticed the proportional layout of the main house, as seen in this view above. What makes this particularly worthy of study is how simple the design, yet how beautiful. If it were not for the Palladian style portico (the grand columned porch that leads to the entrance of the building) the main house would be just a square block. One might argue that there was very little in terms of design to differentiate it from a modern housing block.

Both have windows and doors in a rectangular facade. Yet the modern building is no tourist attraction. In fact it was described in the website where I saw it as one of the seven most notorious housing projects in the US.

What gives Attingham House its beauty is the proportion? Proportion is the consonant relationship between three or more objects of different size. You cannot have pleasing proportion when everything is the same size as in the modern building shown. The basis for theories of harmonious proportion are consensus - people have observed since the ancient Greeks how most people react psychologically to different proportions. The Attingham House proportions are made apparent by the different window sizes associated with the three stories. If you count the panes of glass there are 6 in the lower floor, 4 in the second floor and 2 in the upper floor windows. The proportion would be expressed mathematically as 3:2:1. This corresponds exactly to the traditional proportions based upon the lengths of pipes that produce pleasing combinations of musical notes developed by the ancient Greek philosopher, Pythagoras (who we talked about in the last of these features, here.)

It seems that modern science is beginning to catch up. Someone recently contacted me to tell me about this book by Colin Ellard, Places of the Heart in which a psychologist conducts studies to see how different designs affect the mood of people.

If the designers of modern housing projects had made use of such proportions, even such mass housing could elevate the spirit in the same, way.

Behold the lamb of Advent!

Here's an enterprising way to draw people into the liturgy...and to prepare for Advent:

This from Jesson Mata, recently appointed Director of Office of Divine Worship for Archbishop Sample in the Archdioces of Portland, Oregon. He is also the Archbishop's Master of Ceremonies. He has done a blog posting on how to cook a dish - 'lamb with earthy vegetables'. At one level this is a simple cooking demonstration but he connects it with the liturgical season of Advent and offers it in anticipation of the coming season. This highlights the point that feasts and fasts are not just religious observances or names given to the liturgical celebration but are about eating (or not as the case may be).

There can be a tendency to think of the Lamb's supper, in the Mass, as a symbolic replication of conventional meals, but in fact it is the other way around. Formal meals are quasi-liturgical activities that are derived from and point to the holy banquet.

Similarly, the choice of vegetables reflects the earthly season, which points us to the seasons of sacred time. It is sacred time that is the model for earthly time, and not the other way around. He also gives it a Oregonian connection by making use of locally grown produce.

Anyway, here is the posting, complete with the video of Jessen in his kitchen...

My only criticism would be the same one I have of all haute cuisine - the size of the helping. If I was presented with a meal like this I could probably eat about 10 of them and still be hungry. Then again, I am a bit of a Philistine when it comes to food and tend to see quantity and quality as the same thing!

Jesson also chooses a very interesting modern image of Our Lady - it has a hazy, gothic feel to it which I think works very well. I didn't recognize it so asked Jesson about it and he referrred me to this link here. The artist is Kay Eneim and it was painted in 2007. As she explains its is 'copied' from a 14th painting by Spanish gothic master, Pere Serra. She explains her reasons for focussing just on Our Lady (the original has many saints surrounding her). It is to her credit that she did not seek to do something wholly original (as someone working in the modern idiom might) This selective copying, changing only what is necessary to make it accessible to the modern eye, is how artists should approach the reestablishment of these traditions today as living traditions.

Denis McNamara on Architecture, part 3: the Jewish Roots of Church Architecture

Denis is on the faculty of the Liturgical Institute, Mundelein; and his book is Catholic Church Architecture and the Spirit of the Liturgy.

Drawing on St Gregory the Great and Pope Benedict, he refers to three eras in time: the pre-Christian time of the Jewish faith, the 'time of shadow'; the heavenly period to which we all look and which is called the 'time of reality'; and the time in between, which we occupy. This is the 'time of image'. The liturgy of the time of image both recalls the sacrificial aspects of the previous age and anticipates and gives us a foretaste of our heavenly end. Having described time in this way, Denis then goes on to explain how good church architecture reflects this.

As I was listening to this, I was reminded of how in art, again according to Pope Benedict, there are three authentic liturgical traditions. The baroque 'at its best' reveals historical man, that is man after the Fall but with the potential for sanctity as yet unrealised. It occured to me that this might seen also as the art of the time of shadow (after all it is characterized visually by deep shadows contrasted with the light of hope).

The art of eschatological man - man fully redeemed in heaven - is the icon. This is the art of the 'time of reality' and visually there are never any deep cast shadows in this form. Every figure is a source of light.

The art of the in-between time is the gothic, which I always called the art of our earthly pilgrimage. Like the spire of the gothic church it spans the divide between heaven and earth. Its form reflects the partial divinization of man which characterizes the Christian who participates in the liturgy. This might then be called the art of the 'time of image'. As before, any are curious to know more about this analysis can find a deeper explanation in the book the Way of Beauty.

In contrast to the artistic forms, in which the form of each tradition focusses on one age, the form of the church building, regardless of style, must reveal all three ages simultaneously. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bLj2ivFh75M

What is a church? What is the Church?...and How are They Connected?

The essence of Church as institution, and church as building. And how understanding this is what opens up the 'Pope Francis effect' to all people.

A friend was telling me recently how much he is enjoying meeting regularly with a group of friends, a mixture of Catholics and non-Catholics, to read the bible and pray together. From what I gathered, it had started as much for the sharing of friendship and conviviality as it was to explore different ideas of Christianity, but gradually the development of personal faith had become a more and more important part of it.

What had struck him, he told me, was how the different understanding of the church is was proving a stumbling block in explaining his Faith to his friends. I thought it was worth summarizing our discussion of this here, because it relates directly to beauty and worship and how we engage with the culture; and this is something, I suggest, that we can see in Pope Francis as I have been describing in recent articles.

If there was a quick way to describe the different ideas of what a church (as an institution now, not the building) is, then it might be this: for his protestant friends, their understanding of a church is of a community united by common belief. It is the creed, what is believed in common, that makes the church. That community can be local, as in a parish; and it can much wider, something that links many parishes together. Catholics believe this too, but there is something else that defines a church and is present, we believe, only in the Church. That is common worship.

In fact, for the Catholic this identity of common worship is the most important thing of all. All of the Church's activity is directed towards right worship for it is in its heart, at the Eucharist, we encounter personally, the living God. This is the foundation of our personal relationship, coming before emotions and feelings about God (which may be very good nevertheless). This is the optimal place to respond to the love of God so that in accepting it, we are transformed, supernaturally, as better lovers and, for all our personal inadequacies, become more capable of loving other.

In his book, the Spirit of the Liturgy, as my friend pointed out, Pope Benedict talks about how it is natural to man to worship God. If this natural tendency is distorted or not given full expression then it has a profound effect on us as people. The saying of the Church Fathers going back to the early centuries of the Church that describes this effect is lex orandi, lex credendi - rule of prayer, rule of faith. This expression tells us that it is how we pray in the liturgy more than anything else that forms what we believe in. This is why, if you want to destroy belief, you attack the liturgy. Accordingly, we believe that because the wider culture is a manifestation in all that we do of our attitude to God - art, music, architecture even the mundane activities of daily life, if you want to restore the culture you restore right worship in our churches.

So how do we know how to worship properly? We believe that this was revealed to us as much as Holy Scripture. Both the form of worship and holy scripture have been preserved in what we call Tradition. We believe that we are not at liberty to change it and in fact would not want to, because this is offered to us not as a constraint, or as a rod to beat us with, but rather as a gift. It is a heavenly path, that shows us how to love God adequately, so that we can be capable of accepting his love. This is why in the last two articles I wrote about Pope Francis I suggested that the optimal way for us to shine with the light of Christ and to know how to love man effectively is a full and active participation (properly understood) in the liturgy that leads to a supernatural transformation. That liturgy is not just any form of worship but it is the sacred liturgy that God has given us.

In the Spirit of the Liturgy, Pope Benedicts talks of the fault of the Isrealites who were worshipping the golden calf as that of worshipping in a way that differed from that which God had told them to do (in the Jewish liturgy). In our own way, if try to modify the liturgy from what is ordained we participate in the same flaw.

This importance of the liturgy to the identity of the Church is reflected in the way that the Catechism of the Catholic Church defines it. It refers to the other understanding of church as community, but very clearly places that of worship as the highest: 'In Christian usage, the word "church" designates the liturgical assembly, but also the local community or the whole universal community of believers. These three meanings are inseparable. "The Church" is the People that God gathers in the whole world. She exists in local communities and is made real as a liturgical, above all a Eucharistic, assembly. She draws her life from the word and the Body of Christ and so herself becomes Christ's Body.' (CCC, 752)

That is what the Church is as an institution, but how does that relate to the church as a building? The two are intimately connected...or they should be.

If you recall the last posting I made, in which Denis McNamara talks of the importance of beauty in architecture. He describes how one of the important attributes of the church if it is going to be beautiful is that it must communicate to us - radiate - through its form just what it is. In fact this is how you define beauty: it is the 'radiance of being'.

If a church is going to communicate its 'churchness' to us it will reveal in outward signs what it is for. Now we can see what has been the cause of so much ugliness in church design especially in the last 75 years. Architects did not seek to reveal the full purpose of the church to us through its forms. There was a neglect of the true liturgical purpose of the church and too much emphasis on human fellowship and community. For a church to be beautiful it must not only look like a place of community, it must also, crucially, look like a place of worship. And that worship must be right worship. Furthermore it must be a symbol of what the Church as in institution is, the body of Christ and relate to God the Son. Practically this last aspect might have been achieved,for example, by basing the design features on the porportions of an idealized man.

Someone who does not understand all of this and how it can be reflected in form cannot create a church that looks like a church, and so cannot create a beautiful church (except by luck).

By the way, as you look at the photographs, which are all churches, ask yourself two questions: first, do I think it is beautiful?; and second, could I tell it was church without being told so (or having an obvious sign such as a cross).

Denis McNamara on the Meaning of Beauty and its Importance in Church Architecture

In this short video Denis McNamara talks about the nature of beauty and then talks about it in the context of sacred architecture (scroll to the bottom if you want to go straight to it and avoid my comments!). Denis is on the faculty of the Liturgical Institute, Mundelein; and his book is Catholic Church Architecture and the Spirit of the Liturgy.This is the second in the series of 10 which I will be featuring in coming weeks.

In this video, Denis points out that beauty is not simply 'in the eye of the beholder' but is a property of the object itself, the thing that we are judging to be beautiful. He is asserting the the principle of objective beauty - it is in the object percieved; and objecting (if you'll forgive the pun) to the opposite principle, the idea of subjective beauty - which would be to say that it is simply a matter of personal taste of the person - the subject - who is seeing the object.

He defines beauty as a property of something that 'reveals its ontological being'. Another way of putting this was given to me by Dr Caroline Farey of the School of the Annunciation in Devon, England. She defined beauty as the 'splendour of being'. Both definitions are telling us that beauty is a property of something that reveals to us what it is. So in the context of this talk, to be beautiful a church must look like church. It must appeal to our sense of what a church is.

As a bit of supporting anecdotal evidence for the definition that Denis gives: when I was a high school physics teacher in England many years ago, at the end of term I used to present the class with a piece of mechanical equipment made in Victorian times. It had cogs and moving parts exquisitely machined in polished brass. No one in the building knew what it was for, and we couldn't tell from looking at it what its purpose was (I never found out). Nevertheless, the precision and harmony of the motion its parts when turned were such that all assumed that it must have one. I would bring this into the classroom and without comment place it down on the table in front of them; I would let them look at it for a few moments. Then I would ask the question: 'Do you think this is beautiful?' Every time the response of the students was the same. They didn't answer yes or no, the always asked: 'What is it?' These were 17 and 18 year olds who had never studied aesthetics and and it was a school in London that had no particular Catholic or even Christian connections. Yet these students knew instintively that they could not answer the question, 'is it beautiful?' without knowing what the object was.

As I see it, this establishment of principles of beauty should not be interpreted as a way of proving (or disproving) that something is beautiful. Any attempts to create 'rules of beauty' to that end will always fall flat in this regard. That is not to say that there are not guiding principles, but that these are better thought of in the same way as the rules of harmony and counterpoint in music. All beautiful music makes good use of them; but not all music that obeys the rules of harmony and counterpoint is beautiful. There is always a intuitive element that relates to how they are employed that cannot be accounted for definitively when creating beauty - this is what marks the good composer from someone who just has technical understanding.

In the appreciation of beauty, there is always a subjective element present. This does not compromise the principle of objective beauty, however: some people are able to recognise beauty and some are not. Ultimately we don't know for certain who has this ability and who doesn't. This lack of an ultimate and perfect authority to whom we can appeal means that in the end we rely on the best authority we have, tradition. Tradition, in this context can be thought of as a consensus of the opinions of many people over generations as to what is beautiful and what is not. It is not a perfect guide, and clearly is less reliable the more recent the work of art we are judging, but it is the best we have.

https://youtu.be/-c3JWNZSrDI

Pope Francis's message to give to the poor: should we sell the treasures in the Vatican and distribute the proceeds?

I think not! Some time ago, on the final Monday of Lent, Mass at Thomas More College was celebrated by one of the monks from St Benedict's Abbey in Still River. As usual, we got a stimulating and challenging homily. It challenged us to give to the poor, but not in the way that we often hear.

The gospel passage on this occasion was about Martha and Mary: Martha tended to the guests and Mary washed Jesus feet with expensive nard, a fragrant ointment. Unusually, (in my experience at any rate), the homily spoke not so much to the contrast between Martha and Mary, but between Mary and Judas. It was the latter who suggested that the money spent on nard would have been better given to the poor. Here was a lesson about allocation of resources. Mary made the right choice, we were told, in choosing Christ even before giving to the poor. Then an even more interesting point was made. There is an equivalent choice facing us today every time we have to decide about having beautiful churches and art, intricate vestments, ornate jewel-studded chalices and so on. Is it right to direct money to these things when there is poverty? The answer is yes when these things, through the liturgy, elevate the souls of the faithful to Christ and this is greater than giving to the poor.

However, in order to understand how this can be so, some additional points must be made. First is that there is a point beyond which spending money on ornamentation of churches would constitute extravagance. But provided that point has not been reached then spending money on that nobler end is not asking the poor to make a sacrifice either. This may surprise some people but it is true. First of all, all of us, rich or poor, can go to church and need our souls saving, so the poor benefit spiritually from the beauty of the church and the liturgy as much as the rich do. Second, is that when we see the greater picture, the poor will benefit materially as well. It will inspire the rich to give to the poor directly. Further to that it will allow for the generation of greater wealth for the benefit of the poor. This is the principle of superabundance at work.

It occurred to me as I pondered on this afterwards that it is this last point that escapes so many people. Life is not a zero-sum game. Love is always fruitful - and when it is it invokes the principle of superabundance which means that something is created out of nothing. The miracle of the loaves and fishes applies to wealth as well when we place Christ first. Inspiring holiness will not only cause people to give more of their wealth to the poor, it will also mean that love permeates each personal interaction to a greater degree, including economic ones. As a consequence, their economic activity more superabundant. It is a double whammy! More wealth is generated to for rich and poor alike and those for whom it is generated are more inclined in turn to give to others who need it. This is the principle of good stewardship.

It is not surprising that critics of beautiful churches should not be aware that the supernatural has an impact on the creation and distrubution of wealth and on the distribution of social justice. Quite apart from consideration of the spiritual aspects of this, which require faith in order to be accepted, it is a basic principle of economics that seems to be beyond so many people who really ought to know better - right up to the level of finance ministers. Wealth is generated out of nothing through economic activity. It is superabundance that creates wealth. Once we realise this then it becomes obvious that tax policy, for example, will be effective if directed towards promoting wealth generation as well as wealth redistribution. (For any that are interested, I have written more of my thoughts on this in an article called Beauty, Business and Liturgy - A Theology of Work and the Entrepreneur.)

It is also the reason, incidentally, that there is such fear about the availability of resources for the future that result in advocating population control, contraception and abortion. Without the realisation that man's ingenuity, inspired by God, can invoke the principle of superabundance to allow greater things to emanate from less, it is impossible to believe that we can live beyond the next generation. This is not to advocate irresponsible use of the world's resources, rather to say that there is more to consider than just the material.

Think now of Pope Francis's call to charity and the poor and his citing of St Francis of Assisi as a model. I claim no insights as to how the Holy Father hopes to see this manifested, but his words have inspired me to think about how I might contribute to what he asks for. Certainly it is true that St Francis himself and the Franciscan order generally is known for their concern for the poor and the model they give of personal poverty. However, St Francis was also told to rebuild Christ's Church. He did both and he did both lovingly and beautifully. So many of the great artists from the time of Francis were third order Franciscans or worked for them at the very least, and they were great innovators - Giotto, Cimabue, Simone Martini, Raphael, Michelangelo. They were contributing to the building of great and beautiful churches and this is evidence, I would say, that points to strong belief in the value of the liturgy. Furthermore, these were innovators who were contributing the creation of a whole new culture of beauty, which through a greater appreciation of nature also fostered huge progress in natural science that generated material wealth for society. All of this is consistent with these twin aims of rebuilding the Church and caring for poor. When you rely on God you tap into the infinite. Inspiring people, rich and poor alike to come closer to God will create benefits in every area of our lives.

So it is only those who have a limited either-or mentality in regard to these things who would interpret a call to help the poor as one that also diverts money away from the support of beautiful churches and liturgy.

There is one argument for less ornate and simpler decoration in churches that is valid. That is one put forward by St Bernard of Clairveaux. If the beauty of the church is so alluring that it acts to distract us from Christ, then it is problematic. If you want to know if this applies to you...then ask yourself when you close you eyes: does your imagination takes you to somewhere lower that the art of the churches, or somewhere higher and closer to heaven. If you naturally think of things lower, then beautiful art in churches is beneficial to you. Those who are hindered by beauty in churches are exceptional. Bernard who was a lot higher up the spiritual slopes than most of us was clearly someone for whom the problem was the opposite. The imagery of the church was lower than the natural place of his imagination, and so were a distraction to him.

The Franciscan, by the nature of their calling, are out engaging with the world, and so, perhaps, the beauty of their churches was calculated to ensure that their prayer and their liturgical imaginations were raised up to the source of their love for the poor. Whatever the precise reason, as one of the spiritually weak whose imagination runs riot if left to its own devices, I am always grateful whenever a church and the liturgy are beautiful.

So please, keep everything in Rome. Except, that is, for the ugly concrete buildings and abstract garish stained glass windows from the 1960s, you can sell those...if anyone will buy them.

Vermeer - Martha and Mary

Luca Giordano - The Good Samaritan

Ribera - St Francis

Franciscan monastery Assisi

...and if you're fed up with reading and looking and want to start creating beauty, here's a unique sacred art class - learn the style of the English gothic psalter...

What is the cause of the Pope Francis effect? It is nothing new. On the contrary, it is his conformity to tradition!

He is a model of the New Evangelization that we can all imitate. After his visit to the United States, the sense is that Pope Francis has done a remarkable job in connecting with people beyond the Church. True, there is constant argument about what he actually says, what people want him to say and what he really means. But despite the confusion no one can doubt that he has a knack for connecting with people. Just today, as I write this, I had a spam email from a political candidate who is, as far as I know, an avowed socialist asking me to vote for him with a connection to a speech he made praising Pope Francis because of his concern for the poor. (I am not entitled to vote for anyone in the US incidentally so he had wasted his time even if I agreed with thim). It is interesting that this should happen despite the fact that Pope Francis has repeatedly condemned socialism and a the fact the the candidate wants to use Francis to push his agenda, indicates how strong his public image is. My reaction to this was to think that this is not an argument for me to vote for socialism, as the candidate thinks; but rather one for the socialists to realise that their aims would be better met if they converted to Catholicism! Stranger things have happened!

I am presenting three articles about him to mark the occasion of his visit, sparked off by a conversation with a friend who told me that she had noticed how many of her friends, especially non-Catholics seemed to warm to him. We were asking ourselves why he is so popular. Is it really just that the non-Catholics like him because he sounds as though he is reversing Catholic teaching? I don't think so as you'll see. You will see that I am largely still optimistic about the Franciscan papacy. I do hope that I feel the same after the synod on the family which is taking place as speak :)

Two of these three contain some things I have written before, but represented in this new context.

How does he do it? The answer, I believe is quite simple and it is nothing to do with PR tactics or political spinning if ever there was a Pope that really seemed less interested and less skilled in the art of polished media manipulation it is this one. Rather, to the degree that he is connecting with people and drawing them to the truth, what is drawing people in is supernatural.

Those who do not believe in the supernatural will not account for it in this way, even if they like him, but that doesn't invalidate the point. I suggest that what we see here is a case of the New Evangelization at work. For Catholics it works like this - or rather it ought to if we followed the Church's teaching: by our participation in the sacramental life, we are transformed supernaturally so that we partake of the divine nature. By degrees in this life, and fully in the next, we enter into the mystery of the Trinity, relating personally to the divine godhead by being united to the mystical body of Christ, the Church. When this happens we shine with the light of Truth as Christ did at the Transfiguration - people see beauty and love in our daily actions because they are, quite literally, graceful. They see the joy in our lives. This is what people are seeing in Pope Francis, I suggest. And here is the great fact that so often seems to be missed, the Pope is not especially blessed in participating in this. On the contrary, what he is showing us something that is available to every single one of us, low or high. This is what he wants us to believe.

How do we get this. The place of transformation, if I can put it like that, is our encounter with God in the sacred liturgy, most especially the Mass and the Liturgy of the Hours with the Eucharist at its heart. All of the Christian life is consummated in this life by our worship of God. It is by accepting the love of God first, and most powerfully in the sacred liturgy, that we are transformed into lovers who are capable of loving our fellow man and the Franciscan way.

This message is precisely the same as Pope Benedict XVI and John Paul II before him. In this sense Francis is utterly traditional. He is, I suggest, able to be the Pope of evangelization because he comes after the work of these two great Popes who did so much, beginning with John Paul II, in the chaotic aftermath of Vatican II to implement the true message of the council. Contrary to what is often reported, he does not stand out against his predecessors. Rather, in his own way, he is in conformity with them.

Let us take the case in point. What is his view on the liturgy and the need for supernatural transformation. His words and actions indicate that he understands that all Benedict XVI did was not only necessary, but he now wants to continue in the same vein. This may be a surprise to many, but this is why I think so.

I have heard some express disappointment that there was not enough emphasis on the liturgy in the apostolic exhortation of Pope Francis, Evangelii Gaudium. It is true that there is little direct reference to the liturgy, and so it might appear at first sight that there is little interest from the Pope on this matter.

I have no special access to the personal thoughts of the Holy Father beyond what is written, so like everyone else, I look at the words and ask myself what they mean. In doing this, given that the Holy Father is for the most part articulating general principles, and given that I am not in a position to ask him directly, I am forced to interpret and ask myself what does he mean in practice? And then the next question I ask myself is this: to what degree does this change what the Church is telling me I ought to do? Or rather is he simply directing my attention to an already existing aspect of Church teaching that he feels is currently neglected?

If I want to, of course, I can choose to look at it the Exhortation as a manifesto in isolation and assume that is the sum total of all that the Pope believes; or I can choose to see this in the context of a hermeneutic of continuity. In other words I will assume that in order to understand this document, I must read read it as a continuation of those that went before, and this means most especially the period just before the advent of Pope Francis, that is, the documents of the papacy of Pope Emeritus Benedict. So unless I see something that contradicts them, I will assume that they are considered valid and important still.

If we read it this way, then because he doesn't have much to say on any particular issue, it doesn't mean that he opposes it, or even that he thinks it is unimportant, rather it means that he feels that what is appropriate has already been said and so has little or nothing to add.

This is what traditionalists within the Church say that the liberals failed to do after Vatican II. Sacrosanctum Concilium must be read, we have been told (and I think quite rightly) in the context of what went before to be properly understood; and is one reason why Pope Benedict XVI encouraged celebration of the Extraordinary Form of the Mass - so the people could learn from and experience of that context, so to speak. I accept this argument fully, and therefore, it seems reasonable to read the writings of the new Pope in this way too.

Now to Evangelii Gaudium and the liturgy. The following paragraph appears:

'166. Another aspect of catechesis which has developed in recent decades is mystagogic initiation.[128] This basically has to do with two things: a progressive experience of formation involving the entire community and a renewed appreciation of the liturgical signs of Christian initiation. Many manuals and programmes have not yet taken sufficiently into account the need for a mystagogical renewal, one which would assume very different forms based on each educational community’s discernment. Catechesis is a proclamation of the word and is always centred on that word, yet it also demands a suitable environment and an attractive presentation, the use of eloquent symbols, insertion into a broader growth process and the integration of every dimension of the person within a communal journey of hearing and response.'

So what is mystagogical initiation? What the Pope is saying seems to me be referring to and reiterating what was said in the apostolic exhortation written by Pope Emeritus Benedict, Sacramentum Caritatis. This is headed 'On the Eucharist as the Source and Summit of the Church's Life and Mission' and was written following a synod of bishops (I don't know, but I'm guessing the Pope Francis was present). In a section entitled 'Interior participation in the celebration' we have a subheading 'Mystagogical catechesis' in which the views of the gathered bishops are referred to specifically:

'64. The Church's great liturgical tradition teaches us that fruitful participation in the liturgy requires that one be personally conformed to the mystery being celebrated, offering one's life to God in unity with the sacrifice of Christ for the salvation of the whole world. For this reason, the Synod of Bishops asked that the faithful be helped to make their interior dispositions correspond to their gestures and words. Otherwise, however carefully planned and executed our liturgies may be, they would risk falling into a certain ritualism. Hence the need to provide an education in eucharistic faith capable of enabling the faithful to live personally what they celebrate.'

This is so important that the following paragraph was included also:

c) Finally, a mystagogical catechesis must be concerned with bringing out the significance of the rites for the Christian life in all its dimensions – work and responsibility, thoughts and emotions, activity and repose. Part of the mystagogical process is to demonstrate how the mysteries celebrated in the rite are linked to the missionary responsibility of the faithful. The mature fruit of mystagogy is an awareness that one's life is being progressively transformed by the holy mysteries being celebrated. The aim of all Christian education, moreover, is to train the believer in an adult faith that can make him a "new creation", capable of bearing witness in his surroundings to the Christian hope that inspires him.' [my emphases]

I don't think it is possible to make a stronger statement on the centrality of the liturgy to the life of the Church and the importance of the faithful understanding this and deepening their participation in it. There is no reason to believe that Pope Francis is dissenting from this, in fact quite the opposite - he seems to be referring directly to it and re-emphasising it. If this is what he doing, then he might be stressing the liturgy in a way that even some Catholic liturgical commentators do not. (Indeed, one wonders if the first step in mystagogical catechesis for many is one that begins by explaining the meaning of the phrase 'mystagogical cathechesis'!)

I wonder also how many Catholic colleges and universities (I am thinking here of those that consider themselves orthodox) actually make mystagogy the governing principle in the design of their curricula? How many Catholic teachers, regardless of the subject they are teaching, consider how what they are teaching relates to it? If we believe what Pope Benedict wrote (and Francis appears to be referring to) then if I can't justify what I teach in these terms, then it isn't worth teaching.

Am I choosing to interpret Pope Francis the way I wish to see it too? Perhaps - like most people I would always rather that others agreed with me than the other way round. Only future events will demonstrate if I am correct. However, his papacy so far seems to support this picture: while there are some new things, I have read nothing that that explicitly rejects anything that developed during the previous papacy (that's not to say that he hasn't said things that could be interpreted that way if we chose to). In fact, the signs seem to indicate the reverse: his appointment as the Prefect of the Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments has told us the he was directed explicitly by Pope Francis, to 'continue the good work in the liturgy started by Pope Benedict XVI,' He has broadened and strengthened the mission of the Anglican Use Ordinariate, which is all about enrishment of the liturgy in the English vernacular. I wrote about this in an article 'Has Pope Francis saved Western culture?'. And I have read articles in the New Liturgical Movement website and elsewhere heard anecdotal evidence that he has rejected direct appeals from deputations of emboldened liturgical liberals asking him to ban the Extraordinary Form and celebrating the Mass ad orientem (I attended at a papal Mass in St Peters that was celebrated by him in Latin two years ago).

His personal preferences may not be precisely the same as mine, and I will freely admit that in some of the specifics of matters where I am not bound to agree with him - matters of science and politics for example. But in but in his reinforcement of matters of the Faith, I don't hear anyone telling me that the views I had three years ago need to be changed at all. So in regard to liturgy, art, music and even free market economics (despite the alarm of many), I see nothing as yet that worries me at all...quite the opposite.

Denis McNamara on the Theology of Architecture

Here is the first of a series of 10 short videos (about six minutes each) presented by the architectural historian Denis McNamara of the Liturgical Institute in Mundelein. I had the pleasure of meeting him recently and sitting in on one or two of his classes. They were excellent.

These talks introduce succinctly and well, I feel, some of the themes that I heard him talk about in his classes. He is a good and entertaining teacher and speaker and this comes across in the videos. You can find more detail of the subject matter in his book, Catholic Church Architecture and the Spirit of the Liturgy.

What was of great interest to me was to see how he tackled issues for which there are parallel problems in sacred art. For example, how do you reconnect with tradition without falling in the error of historicism? Historicism is an undiscerning respect for the past that says, in simple terms: 'Old is always good; new is always bad.'

The corrollary of this has to be considered too: to what degree should we use aspects of contemporary architecture? How can we ensure that the form we are using connects with people today, while ensuring that we don't compromise the timeless principles that are essential to make it appropriate for its sacred purpose? You might say that what we want to do is to be able to innovate if necessary while avoiding the errors of modernism ('new always good; old always bad') or post- modernism ('anything is good if I think it is').

When I was considering just these questions in art, the only way I could respond was to try to look for a theology of form that connected the material form to the truths that the artist was trying to convey. If we understood this, I thought, then it would give us the freedom to innovate without stepping outside the authentic traditions of liturgical art. (A large part of my book, the Way of Beauty is devoted to consideration of this.)

It seems to me that this is just the conclusion that Denis has drawn too. In this video he introduces the idea of the theology of form for architecture by which the church building becomes a symbol of the mystical body of Christ. You might say the church manifests the Church in material form and in microcosm, He refers to this as a 'sacramental theology' of architecture.

In the nine videos that follow (which I will be posting weekly with a short introduction each time) he unpacks some important parts of this theology for us. If you are impatient to see them, you'll find them on YouTube!

https://youtu.be/2PDWXMMgy9c?list=PLmb-kTzyYnt5i14gShUc1ZYNPGTqG7P6p