What a man who has brain damage has taught me about love; and what it reveals about the 9th-century theology of sacred art.

Man is Body, Soul and Spirit! Why We Mustn't Forget the Spirit

Liturgical Art and Liturgical Man

A 7th Century Saint Describes How We Participate in the Transfiguration and Shine with the Light that will Save the World

The spirit is the mind's eye through which we see God, face to face, and by which we partake of the divine nature, and are transfigured, in this life by degrees, through our participation in the mystical body of Christ. Here is a quotation from a 7th century Greek Father, St Anastasius of Sinai. I read it in the Office of Readings for the Feast of the Transfiguration. This is from a sermon by the saintwritten for this day.

'Let us listen to the holy voice of God which summons us from on high, from the holy mountain top. There we must hasten - I make bold to say - like Jesus who is our leader and has gone before us into heaven. There, with him, may the eyes of our mind shine with his light and the features of our soul be made new; may we be transfigured with him and moulded to his image, ever become divine, being transformed in an ever greater degree of glory.'

The spirit is the mind's eye through which we see God, face to face, and by which we partake of the divine nature, and are transfigured, in this life by degrees, through our participation in the mystical body of Christ. Here is a quotation from a 7th century Greek Father, St Anastasius of Sinai. I read it in the Office of Readings for the Feast of the Transfiguration. This is from a sermon by the saintwritten for this day.

'Let us listen to the holy voice of God which summons us from on high, from the holy mountain top. There we must hasten - I make bold to say - like Jesus who is our leader and has gone before us into heaven. There, with him, may the eyes of our mind shine with his light and the features of our soul be made new; may we be transfigured with him and moulded to his image, ever become divine, being transformed in an ever greater degree of glory.'

I have written a number of articles recently emphasising this idea of personal transformation through an ordered and active participation in the liturgy. By this transformation we shine with the light of Christ and experience profound joy in this life. Oh that all Christians could live this, then we might, in turn, see a profound and powerful change in society through their engagement with it. This is what will call people around us into the Church.

This is a force that can change society and change the culture, but it all happens through our everyday human relations. It is tempting to think that we should focus on influential figures, high profile people to win mass attention to our causes. But a publicity campaign is not a personal relationship and cannot touch us in the same way (although it can open the door). For those who think that relying on personal contact will be too slow to effect anything. However, if it really is true, as I have told, that even in a human race of 6 billion, no one is more than six personal relationships apart from anyone else, then this suggests that it is not only the most powerful but also the most efficient way of reaching most people.

Notice also, St Anastasius's reference to (in translation) the 'mind's eye'. This, it seems to me, is the spirit by which we establish the most important personal relationship by which, in turn, the personal transformation described by St Anastasius is acheived.

Past articles describing the anthropology of body, soul and spirit are here and here. In his book The Wellspring of Worship, Jean Corbon describes how liturgy is the means by which we participate in Christ's transfiguration.

A summary of what they describe follows: the spirit is the highest part of the soul. It is that part of the soul which touches on God, a portal for the grace that pours out from God ‘transfiguring’ us into the image and the likeness of God. The divinely created order of the human person is the spirit, which is closest to God, rules the rest of the soul which in turn rules the body. All move together in union and communion with God. It is our participation in the liturgy that establishes this personal relationship with God at the most profound level.

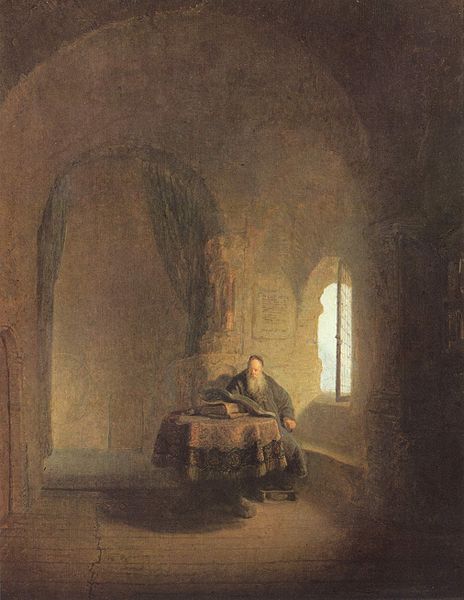

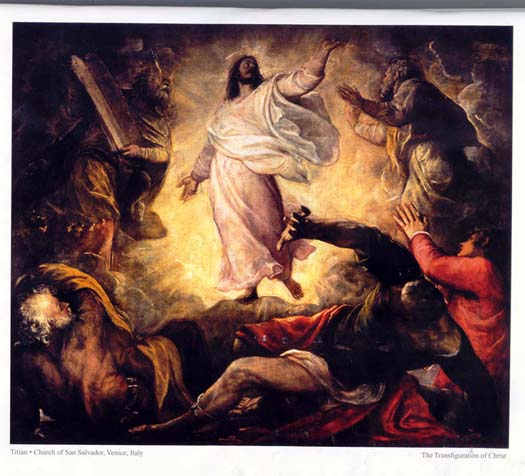

The painting above is by Titian; and below by Rembrandt and it is of St Anastasius in His Monastery, 'the new Moses'. He is venerated in both Eastern and Western Churches.

St Ephrem the Syrian on the nature of man - body, soul and spirit

Over the summer, I read the Hymns on Paradise written by St Ephrem the Syrian. Ephrem is a 4th century saint who lived in modern day Turkey and wrote in Syriac. Although much of what he wrote is liturgical - in the form of hymns, it is theologically rich. There were two reasons why I read this. The first was at the suggestion of Dr William Fahey, who told me that Ephrem described the visual appearance of Adam and Eve both before and after the Fall. This was of interest to me because in his Theology of the Body, John Paul II asked artists to portray man in the manner of Adam and Eve prior to the Fall - 'naked without shame' - in order to reveal human sexuality as gift, that is, an ordered picture of human sexuality. In order to be able to do this, I wanted to do some reasearch to see what the Church Fathers had to say on what Original Man (ie man before the Fall) looked like. In the Christian tradition, we have iconographic art which portrays mankind redeemed and in heaven (Eschatological Man), and the baroque, which shows fallen man (Historical Man) but we have no fully formed tradition in which the form and theology are integrated to portray Original Man and so no visual vocabulary to draw on in order to paint him.

The desire to read him was reinforced recently on my trip to Spain, when I read Pope Benedict's Wednesday address on St Ephrem, a Doctor of the Church, as part of my own personal 'Office of Readings' in the morning (I have written about this here). In this Benedict tells us that St Ephrem is 'still absolutely timely for the life of the various Christian churches...a theologian who reflects poetically on the basis of Holy Scripture, on the mystery of man's redemption brought about by Christ, the Word of God incarnate'.

Over the summer, I read the Hymns on Paradise written by St Ephrem the Syrian. Ephrem is a 4th century saint who lived in modern day Turkey and wrote in Syriac. Although much of what he wrote is liturgical - in the form of hymns, it is theologically rich. There were two reasons why I read this. The first was at the suggestion of Dr William Fahey, who told me that Ephrem described the visual appearance of Adam and Eve both before and after the Fall. This was of interest to me because in his Theology of the Body, John Paul II asked artists to portray man in the manner of Adam and Eve prior to the Fall - 'naked without shame' - in order to reveal human sexuality as gift, that is, an ordered picture of human sexuality. In order to be able to do this, I wanted to do some reasearch to see what the Church Fathers had to say on what Original Man (ie man before the Fall) looked like. In the Christian tradition, we have iconographic art which portrays mankind redeemed and in heaven (Eschatological Man), and the baroque, which shows fallen man (Historical Man) but we have no fully formed tradition in which the form and theology are integrated to portray Original Man and so no visual vocabulary to draw on in order to paint him.

The desire to read him was reinforced recently on my trip to Spain, when I read Pope Benedict's Wednesday address on St Ephrem, a Doctor of the Church, as part of my own personal 'Office of Readings' in the morning (I have written about this here). In this Benedict tells us that St Ephrem is 'still absolutely timely for the life of the various Christian churches...a theologian who reflects poetically on the basis of Holy Scripture, on the mystery of man's redemption brought about by Christ, the Word of God incarnate'.

As Dr Fahey had indicated, there is much useful material written by St Ephrem on Original Man and I am in the process of pulling this together for a longer article. So in this respect, St Ephrem is certainly timely.

I'm sure the style of the translation had a lot to do with this as well (by Sebastian Brock), but I found him pleasurable as well as interesting reading. He was a prolific writer and so there's plenty more to look at in the future!

My reason for bringing all of this up here is that St Ephrem wrote something that caught my eye for another reason in the 9th of his Hymns to Paradise:

Far more glorious than the body is the soul, and more glorious still than the soul is the spirit, but more hidden than the spirit is the Godhead.

At the end, the body will put on the beauty of the soul, the soul will put on that of the spirit, while the spirit shall put on the very likeness of God's majesty.

For bodies shall be raised to the level of souls, and the soul to that of the spirit, while the spirit shall be raised to height of God's majesty.

This describes so well what Jean Corbon described as the transformation that happens to us when we are full participants in the liturgy, as described here. The icon of the transfiguration is an icon of the liturgy, he says, for we participate in Christ's transfiguration when we participate in the liturgy. This passage from St Ephrem suggests that the spirit is a special place in us that is in primary contact with God's majesty that is itself raised to God's majesty and is transfigured. This indicates a special place therefore for the spirit in our participation in the liturgy, for the liturgy is the way in which we ascend, by degrees in this life, to union with God which is complete, as St Ephrem puts it 'at the end' in paradise. It also reinforces an idea that Stratford Caldecot described in his essay, Towards a Liturgical Anthropology. Strat suggests that a lack of full acknowledgement of the spirit as the higher part of the soul has lead, in part, to an incomplete participation in the liturgy since the 19th century at least, and in turn has lead to the Catholic cultural decline that we are all so well aware of.

In another papal address, on St Gregory of Nyssa, Pope Benedict XVI himself referred to this anthropolgy of body, soul and spirit as being part of the tradition of the Church.

To summarise how the spirit relates to the soul here's my understanding: the spirit is the highest part of the soul. It is that part of the soul which touches on God, a portal for the grace that pours out from God 'transfiguring' us into the image and the likeness of God. The divinely created order of the human person is the spirit, which is closest to God, rules the rest of the soul which in turn rules the body. All move together in union and communion with God.

Liturgy and Anthropology: Body, Soul, Spirit

Understanding that man is body, soul and spirit might be step towards establishing a culture of beauty. I have written before, here of the idea that liturgy and culture are linked. Each forms and reflects the other. If this is the case, then the answer to the question of how to reform a culture of ugliness, even a culture of death in any lasting way has its roots in, or at least must include firmly at its heart, liturgical reform.

Understanding that man is body, soul and spirit might be step towards establishing a culture of beauty. I have written before, here of the idea that liturgy and culture are linked. Each forms and reflects the other. If this is the case, then the answer to the question of how to reform a culture of ugliness, even a culture of death in any lasting way has its roots in, or at least must include firmly at its heart, liturgical reform. I read recently Looking Again at the Question of the Liturgy with Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger: the Proceedings of the July 2001 Fontgombault Liturgical Conference, edited by Alcuin Reid. One of the presentations was by Stratford Caldecott, who runs the Thomas More College Centre for Faith and Culture in Oxford. Mr Caldecott argues that the problems lay in the fact that the anthropology - the understanding of the nature of man - had strayed from a full recognition of the spirit as part of the anthropology described by scripture. St Paul for example, talks of body, soul and spirit. There had been tendency argues Caldecott, to equate, or at least insufficiently differentiate between (in our understanding), soul and spirit. (His presentation is online, at the Second Spring website, here. Go to the section on the left that says 'online reading' and then click the title of the article: Liturgy and Trinity; Towards a Liturgical Anthropology.)

I read recently Looking Again at the Question of the Liturgy with Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger: the Proceedings of the July 2001 Fontgombault Liturgical Conference, edited by Alcuin Reid. One of the presentations was by Stratford Caldecott, who runs the Thomas More College Centre for Faith and Culture in Oxford. Mr Caldecott argues that the problems lay in the fact that the anthropology - the understanding of the nature of man - had strayed from a full recognition of the spirit as part of the anthropology described by scripture. St Paul for example, talks of body, soul and spirit. There had been tendency argues Caldecott, to equate, or at least insufficiently differentiate between (in our understanding), soul and spirit. (His presentation is online, at the Second Spring website, here. Go to the section on the left that says 'online reading' and then click the title of the article: Liturgy and Trinity; Towards a Liturgical Anthropology.)It strikes me that such a neglect as a result of the Enlightenment should result in a cultural decline as well as a liturgical decline is made all the more understandible when one considers the role of the intellectus, or spirit, in the apprehension of beauty. In the first part of her little essay Beauty, Contemplation and the Virgin Mary, Sister Thomas Mary McBride, OP describes succinctly in just a few paragraphs, the traditional understanding of beauty and how man apprehends it (and as such I would recommend this piece for anyone seeking an introduction to this subject). She draws on the Latin medievals and states that beauty illuminates the intellectus, describing the apprehension of beauty as the 'gifted perfection of seeing'. Then echoing Caldecott in the connection between intellectus and spirit says: 'In the light of the above, this writer would suggest that the proper place of beauty is in the spirit.'

An appropriate active participation in the liturgy is one that engages the full person in order to encourage within us the right interior disposition. Any participation in the liturgy that does not engage body, soul and spirit therefore does not engage the full person. Our participation in the liturgy is the primary educator in the Faith at all levels. A true conformity of body, soul and spirit is what is desired. One can see that any participation in which consideration of the spirit is neglected (through a balanced active participation of soul and body) will result in therefore necessarily result in a deficiency in our ability to apprehend beauty, which resides in the spirit. This explains this link between culture and liturgy and how important liturgical reform is in our efforts to create a culture of beauty today.

St Ephrem the Syrian who lived in the 4th century AD in modern-day Turkey is a Doctor of the Church and one of the Church Fathers referred to by Pope Benedicti XVI in one of his weekly addresses and whom he encouraged us to read. St Ephrem wrote the following in the 9th of his Hymns to Paradise:

Far more glorious than the body is the soul, and more glorious still than the soul is the spirit, but more hidden that the spirit is the Godhead.

At the end, the body will put on the beauty of the soul, the soul will put on that of the spirit, while the spirit shall put on the very likeness of God's majesty.

For bodies shall be raised to the level of souls, and the soul to that of the spirit, while the spirit shall be raised to height of God's majesty;