'When we give up sin, properly speaking, we’re not making a sacrifice.'

In anticipation of the Second Sunday in Lent, here is another Lenten reflection from a priest from the Institute of the Incarnate Word, IVE, and we are delighted that they have taken the time to do so. This focuses on the nature of sacrifice and is by Fr. Nathaniel Dreyer from their seminary, the Venerable Fulton Sheen Seminary, close to Washington DC.

In common with all that I see in the charism of the Institute of the Incarnate Word, Fr Nathaniel stresses the great joy that is on offer through the Faith. Even in sacrifice, the rewards are greater. This is what attracted me to Catholicism originally - I was lucky I think to be guided to the Church, over 25 years ago now, by someone who was himself a joyful man and was adamant that we can have a happy life in the here and now through Christ.

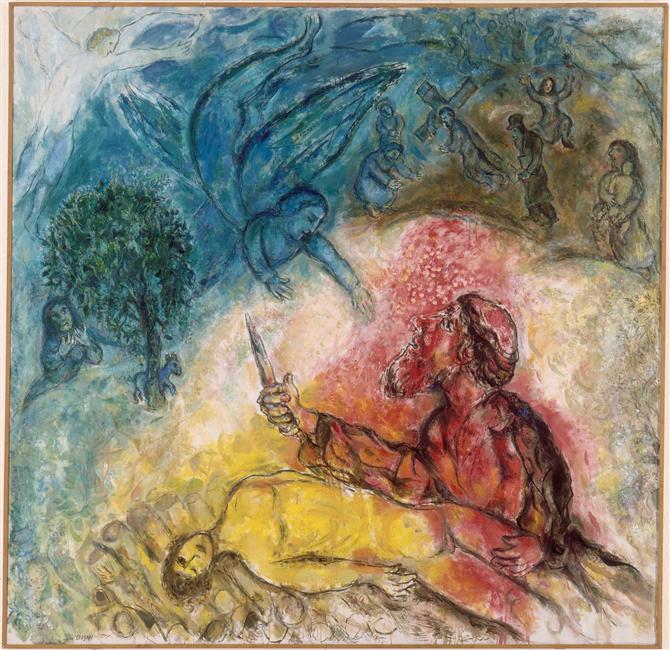

I have chosen the art to accompany this meditation. In the passage below there is a reference to St Ephrem the Syrian's commentary, in which he asserts that Abraham reacted with joy when he saw the ram caught in the bush, because he anticipated that this was the Lamb of God and understood, perhaps albeit dimly, what was to come. The last painting below makes this explicit by showing not a lamb or ram, but Christ on the cross in the scene with Abraham. What is intriguing is that the painter is Chagall, who was Jewish.

Fr Nathaniel writes:

The account of God’s call to Abraham and the near-sacrifice of Isaac cannot fail to rattle us, especially in this time of Lent, when we’re reminded more frequently God calls us to sacrifice. There are three things that really call our attention about the whole scene: first, that initial call from God and Abraham’s response, second, the way God describes Isaac, and, third, the reward that Abraham receives for his willingness to sacrifice. In turn, we can apply each of these to our lives, and consider how we respond to the sacrifices that God asks of us.

That initial call from God and Abraham’s response is the first thing that sticks out. “God put Abraham to the test,” we’re told, “and said to him: ‘Abraham!’ ‘Here I am!’ he replied.” Then God gives instructions on how Isaac is to be sacrificed. First, notice Abraham’s prompt reply: to the sound of his name, a personal call uttered only once, Abraham replies, “Here I am!” Contrast this to Adam and Eve, after the fall, when they hid out of shame, and God had to ask, “Where are you?” although He already knew they were far from Him because of sin. On the contrary, the one who really wants to do God’s will is prompt to reply, and that exclamation, “Here I am!” expresses a willingness to do anything, to go anywhere, and to give up anything. If we are to have truly generous hearts, we can’t set limits on what we will do for God; we can’t tell Him, “This far, but no farther.” We must trust in God; when He calls, and we see clearly what it is He asks of us, we should neither doubt nor hesitate. It’s interesting that God speaks to Abraham in the beginning, but the rest of the interactions that Abraham has with God are done through an angel; God speaks once, and then Abraham must walk the lonely road to the mountain by faith.

Regarding the second, God gives a very beautiful description of Isaac to Abraham: “Take your son Isaac, your only one, whom you love.” It would’ve been enough to say simply “Isaac,” but God emphasizes that Isaac is an “only son” and “beloved.” In other words, God emphasizes the difficulty of the sacrifice. He’s not asking for just any old sacrifice; He’s asking for something that hurts, something that is more precious to Abraham than anything else he has or possesses. He’s asking Abraham to sacrifice the child of the promise, the one he had waited so long for. When we give up sin, properly speaking, we’re not making a sacrifice; there is nothing sacrificial in ceasing to steal, or to lie, or to gossip. Rather, the word sacrifice comes from the Latin sacra, holy or sacred, and facere, to make.

When we make a sacrifice, we are taking something that is good, something we could have without sin, and offering it to God, taking a good thing and making it even better by giving it to the Almighty. Opportunities abound every day for making sacrifices: it might be as small as sacrificing my time in order to be with the sick or the elderly, or even simply to be patient with relatives or coworkers who annoy me; it might be sacrificing a snack or an outing and using that money for charity. However, it could also be something as great as sacrificing my dreams, my hopes, and what I want (or what I think I want) in order to give myself completely to God, be it in a vocation to religious life or priesthood, or to a spouse and family in marriage.

We shouldn’t think that God doesn’t know how hard it is, or how difficult it is to sacrifice. God knows, and He knows better than we do. In Matthew’s Gospel (19:27-30) Peter, speaking for the Apostles and, for all those who leave things to follow Christ, asks about the reward for those who give up everything, even the little they had: “We have given up everything and followed you. What will there be for us?” Notice the list of things that Jesus mentions giving up: “Everyone who has given up houses or brothers or sisters or father or mother or children or lands for the sake of my name will receive a hundred times more, and will inherit eternal life.”

This passage follows right after the rich young man had gone away sad because he had many material possessions, and it’s quite probable that Peter had his material goods in mind: his fishing boat, his house, and so on. The word Peter uses just means, “everything.” Yet, Jesus replies a specific list of things, the majority of which aren’t simply material goods, but, we could say, more spiritual. The list starts with material goods, namely, houses, then more spiritual ones, family members, and ends, oddly, with the Greek ἀγροὺς, meaning “fields” or “lands,” which would seem to be simply material. Yet, it’s important to remember that fields in the Bible aren’t simply physical places: they are part of a family’s inheritance and future, and fields are not only the place where things are planted and grown, but also where cattle can be raised, battles fought, and the dead buried. In other words, fields are full of potential, full of future possibilities and dreams. In our lives we surrender all that to Jesus, and it’s as though Jesus responds by saying, “I know exactly what you have given up for my sake, even more than you know”; indeed, He’s the only one who really knows. The God who tells us through Isaiah, “See, upon the palms of my hands I have written your name” (Is 49:16), and in the Psalm that “our tears are stored in His flask, recorded in His book?” (cf. Ps 56:9), will not let anything we give up be forgotten. He takes all of that, and opens to us a hundred more possibilities as He takes our futures into His hands: as He said through the prophet Jeremiah: “For I know well the plans I have in mind for you—plans for your welfare and not for woe, so as to give you a future of hope” (29:11).

Regarding the third, Abraham receives a great reward for his willingness to surrender everything to God. The book of Genesis presents us with a long list of rewards, but one, perhaps even greater reward, is missing. This reward is mentioned by Christ Himself in John’s Gospel (8:56): “Abraham your father rejoiced to see my day; he saw it and was glad.” Saint Ephrem comments that Abraham rejoiced when he saw the lamb caught in the bush, because he saw in it the future Lamb of God, who was to take away the sins of the world. In that moment, he caught a glimpse of the salvation that was to come, a time when yet another only-Begotten, Beloved Son would head to the summit of a mountain, but this time, that Son wouldn’t escape sacrifice. The rewards from God far outweigh the sacrifices we make for Him, because in them we can catch a glimpse of the reward that is to come. God is not outdone in generosity, and, although the sacrifice might be difficult, God always gives His grace, and “with dawn comes rejoicing.” Lest we forget, the evening of Abraham’s rejoicing probably started out as the worst morning of his life, as he led Isaac out into the middle of nowhere to kill him.

For us, then, we need to be prepared to give everything we have to God. Perhaps, as in the case of Abraham, it will be enough simply to offer it, even though our hearts might break. He might simply ask that we purify our attachment to things, and then leave them to us, with our hearts set on Him alone. Perhaps, though, God will ask that we do indeed surrender it to Him, sacrificing it to Him and His adorable will. What God wants is always what is truly best for us, and we must be convinced of this with the certainty of faith.

If we really want to be saints, then we must be willing to sacrifice everything for Him. What good does anything in this life do, if I’m not willing to give it to God. We can ask ourselves: what is God asking me to sacrifice to Him? What is it that He asks me to give to Him, or to Him through others? Where is my heart set? Where is my treasure? What holds me back from giving everything to God? Through the intercession of Mary, Our Lady of Sorrows, let us ask for the grace to have minds ready for sacrifice, and wills ready to leave everything to follow Christ.