By Margarita Mooney Clayton

This is the first post from The Way of Beauty’s most recent addition to the team, Margarita Mooney Clayton, who is an Associate Professor of in the Department of Practical Theology at Princeton Theological Seminary. She is also the founder and Executive Director of Scala Foundation. In this post she describes her experiences on a silent retreat at the Monastery of Bethlehem in the Catskill Mountains in New York State. She reflects on the distinctions between Christian contemplative prayer and the new-age and Eastern non-Christian forms of meditation that are so popular today.

Margarita writes.

Although I longed for a weekend of total silence, I was scared of that the retreat center I was heading to at the Monastery of Bethlehem in Livingston, NY in the Catskill Mountains warned retreatants of the “austere” conditions they would find. Expecting a death-to-the-world, dark, cold, hungry three days, I spotted Five Guys and Fries off the interstate and stopped.

“Let me fill my belly now while I can,” I told myself.

Greedily, I downed two patties and fries that only count as small because this is America, the land of the plenty. Not to mention I drank three diet cokes to top off my extra dose of morning coffee.

What awaited me, however, in my “cell of solitude” was nothing less than a two-story private chalet with a kitchenette, plentiful hot water and blankets, and a delicious home cooked meal every day, supplemented by practically limitless peanut butter, fruits, and cheese. I grabbed a small coffee maker from the shared supplies, mixing Starbucks Pumpkin Spice and Organic Arabica I found on the shelves.

“This should be advertised as a Glamping Retreat, not an austere retreat,” I thought.

But I couldn’t find the inner peace I longed for. I set out for a hike, hoping to calm my jittery and achy body. So I set out for a hike. Nearly two hours later, I returned to the chalet of solitude with tired legs but eyes enriched by bountiful trees, changing leaves, a lake and birds.

The previous day, in a class on aesthetics and Christian education, I had read about the body and liturgy with my students. In his book The Spirit of the Liturgy, Cardinal Josef Ratzinger (Pope Benedict XVI) explains that external activity of the body influences the internal disposition of the person.. Liturgy trains our bodies to surrender, to reorient ourselves to the resurrection. Our gestures, posture, and breathing all can help or hinder prayer.

One of my student’s questions resonated in my head: Why would God choose such a weak vessel—the human body—as a channel of grace?

I felt like Elizabeth Gilbert in Eat, Pray, Love, who travels the world looking to satiate her appetites for food, meditation and romance. First she stuffs herself with great food in Italy before heading off to a silent meditation at an ashram in India. Unable to be silent, a fellow retreatant nicknames her “Groceries.”

The groceries with which I stuffed my belly were a sign of my lack of inner peace. I couldn’t sit still as the sisters prayed the liturgy of the hours in the stone chapel adorned with magnificent icons. I knew my agitation was not only bodily, it was also spiritual.

But I wasn’t at a Hindu meditation center like the one Gilbert visited in India. Eastern forms of meditation with their roots in Hinduism or Buddhism have expanded in the United States, but they don’t offer what a Christian retreat center can offer.

Christian prayer and Eastern meditation may share an emphasis on stillness, but stillness of Christian prayer is not a sign of nothingness, it’s an awareness of an external being who loves us. The most important part of a Christian retreat is not what I do but what God does.

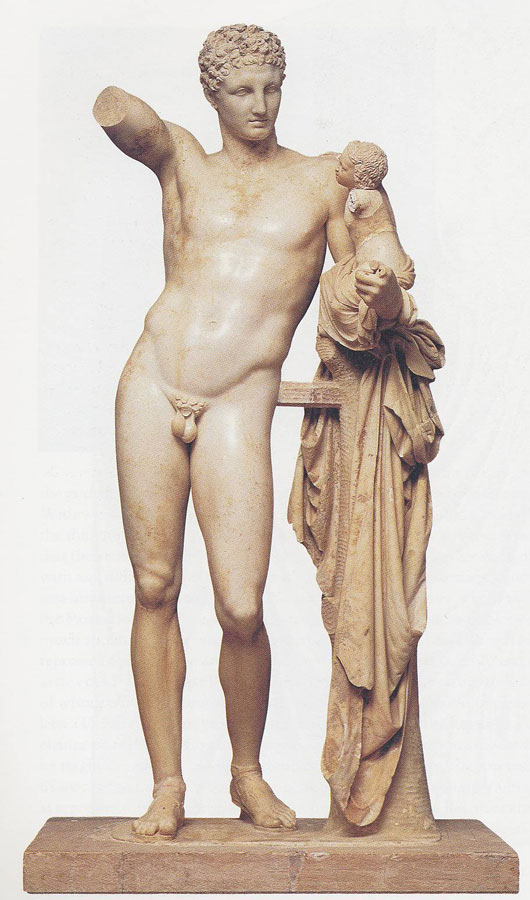

As a student had said in class, summarizing Ratzinger, the mystery of the incarnation is precisely that the eternal divinity took on flesh and blood. God took on human form, becoming man in Jesus Christ.

We are made of dust, but made for communion with God. In my weakness, I can make an act of the will to go on a retreat, indicating a desire to surrender my burdens. A priest of the Franciscan Friars of the Renewal also visiting the retreat center let me break my silence and listened to an outpouring of my burdens. His main piece of advice was to forgive myself. God wants me to receive his love; he knows I’m not perfect but loves me anyway.

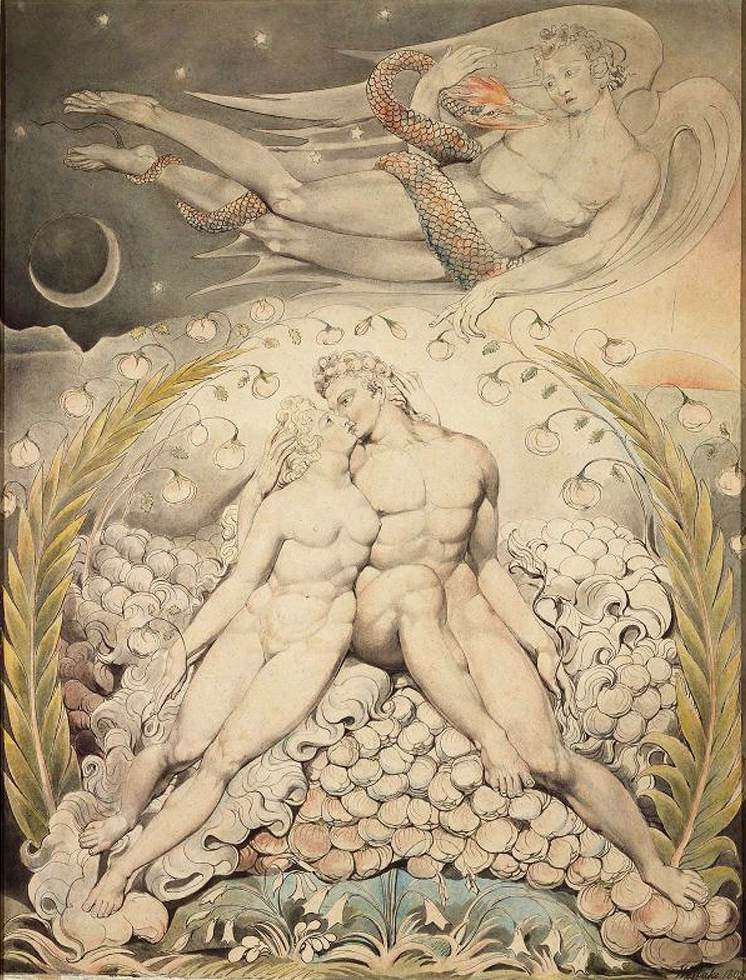

We all struggle with our vessels of clay, with our appetites that distract us from intimacy with God. But regardless, our bodies are an external sign of an inward state. Our bodies are an outward display of an inward truth. Our life with God is here and now, is bodily. Our communion with God is passive and active—we have to be still to hear his calls and respond. Christians seek stillness so as to enter into the dynamic receptivity of God’s love.

Glibert finishes her book finding love in Indonesia—a truly Hollywood ending full of bodily passion. Her story resonated with so many because we live in a time that people long for a spiritual journey that is quieting and filling at the same time.

But the passionate love affair Gilbert describes in her book becomes her second marriage—and then her second divorce.

Everyone struggles to maintain the human loves we so desire. Christianity tells us that we can’t sustain intimacy with others without intimacy with God, which is the key to intimacy with ourselves.

The very limitations of our bodies remind us that intimacy with God is not the result of kind of spiritual Gnosticism. Retreats are not heroic occasions of mystical encounters.

Retreats are times to discipline the body, even at ‘glamping’ style retreat centers which offer solitude but also the beauty of liturgy, bountiful nature and wonderful food. God created the material world. We are called to redeem it.

What we do with our bodies at retreats, and in everyday prayer and living, is part of that redemption.

Stilling our bodies to receive God’s love is needed to experience the lasting the intimacy we all seek with others. It is because we have received that love that we can respond with our bodies, rejoicing in the goodness of creation. Our bodies humble us so that God can exalt us.

Margarita Mooney Clayton is an Associate Professor of in the Department of Practical Theology at Princeton Theological Seminary. She is also the founder and Executive Director of Scala Foundation whose mission is to restore meaning and purpose to American culture by focusing on the intersection of artists, liberal arts education, and religious worship.

The next Scala Foundation annual conference - Art, the Sacred, and the Common Good - takes place in Princeton, April 21, 2023 @ 4:00 pm - April 22, 2023 @ 5:00 pm EDT.

It is recommend to all Way of Beauty readers! I will be there [this is David Clayton writing!] moderating a dialogue between myself, Aidan Hart my old friend and teacher and one of the worlds leading iconographers; and the internationally known Canadian iconographer and podcaster Jonathan Pageau. Aidan is traveling from England to be with us at this event and I can’t wait to be part of it.