"The vocation of man is to work towards the perfection of creation, for the artist this vocation is related in a mysterious way to beauty."

Ceramic Tiles From Portugal - And Resources To Make Them Today

Further to my last post (on how we might bear witness publicly, yet discreetly and beautifully through tiled images cemented into buildings), readers have been coming forward with interesting and useful points. For the following I woud like to thank particularly, Raven W.

First the interesting - a number pointed out that Portugal has many blue and white ceramic tiled images. You can see many of these if you do an image search on 'Portuguese religious tile murals'.

As I dug further I found this photograph of an extraordinary mural on the wall in the town of Avente.

There are charming little decorative details as well. Remember that these patterns reflect a geometry that echoes the mathematical description of the beauty of the cosmos. When we get this right it is decoration with purpose - subtly but powerfully raising people's spirits to God through cosmic beauty so that they might be receptive to the Word.

I then decided to look further and explicitly search for Spanish architecture influenced by the Islamic art, as a style called Mujedar. I found these in the cathedral of Santa Maria de Teruel, in the town of Teruel:

This external adornment is so important in that everybody sees it. If it is done beautifully enough they will not object, I believe. The onus is on us, artists, architects, patrons, that is everybody, to start thinking about this and looking for opportunities for cosmic beauty in every aspect of our environment. (If you want to know more about the theory behind these designs, then I have just created a course as part of Pontifex University's Master of Sacred Arts program called The Mathematics of Beauty. This is an extended presentation of the theory introduced in my book, The Way of Beauty.)

Some of you may be wondering where we can get such tiles today? (Now we come to the useful!) I am not in the building trade so there is probably a lot more than I am aware of. But here are some ideas.

Patterns that reproduce the Victorian neo-gothic church floors are produced today for kitchens and bathrooms. I saw a shop on Chiswick High Road in West London, that had William Morris designs in the shop window. These floor designs began as renovations of English gothic floors, such as the 13th century, Westminster pavement in Westminster Abbey by Victorians such as George Gilbert Scott. I would as happily use these tiles in the sanctuary of a church as in an external walkway:

...and here is a detail of St Albans Cathedral floor, renovated in the 1880s:

For the figurative religious imagery, it had occurred to me that if you can order cups with personalized messages on them online, it has to be as easy to reproduce religious imagery on ceramic now as it is to put 'World's Greatest Mom' on a mug! Sure enough, a reader referred me to this Italian company that offers Catholic religious images through Etsy and they do mail order. Here is a ceramic tile image of the Virgin at Prayer by Sassoferrato:

So there are ways we can start to think about this.

It can be done well or badly - we still need to take care that we don't put this together to create kitsch, but as long as we are aware of that we have a chance. And as GKC said - if something is worth doing, it's worth doing badly!

We finish with something done well. A cloister in the cathedral at Porto, Portugal.

Sacrifice Is Foregoing Something Good! A Reflection for the 2nd Sunday in Lent, from a Priest of the IVE

'When we give up sin, properly speaking, we’re not making a sacrifice.'

In anticipation of the Second Sunday in Lent, here is another Lenten reflection from a priest from the Institute of the Incarnate Word, IVE, and we are delighted that they have taken the time to do so. This focuses on the nature of sacrifice and is by Fr. Nathaniel Dreyer from their seminary, the Venerable Fulton Sheen Seminary, close to Washington DC.

In common with all that I see in the charism of the Institute of the Incarnate Word, Fr Nathaniel stresses the great joy that is on offer through the Faith. Even in sacrifice, the rewards are greater. This is what attracted me to Catholicism originally - I was lucky I think to be guided to the Church, over 25 years ago now, by someone who was himself a joyful man and was adamant that we can have a happy life in the here and now through Christ.

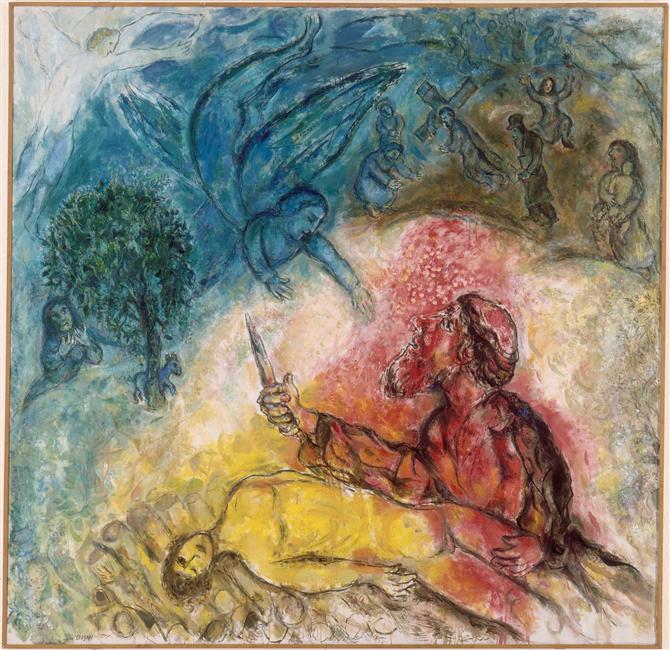

I have chosen the art to accompany this meditation. In the passage below there is a reference to St Ephrem the Syrian's commentary, in which he asserts that Abraham reacted with joy when he saw the ram caught in the bush, because he anticipated that this was the Lamb of God and understood, perhaps albeit dimly, what was to come. The last painting below makes this explicit by showing not a lamb or ram, but Christ on the cross in the scene with Abraham. What is intriguing is that the painter is Chagall, who was Jewish.

Fr Nathaniel writes:

The account of God’s call to Abraham and the near-sacrifice of Isaac cannot fail to rattle us, especially in this time of Lent, when we’re reminded more frequently God calls us to sacrifice. There are three things that really call our attention about the whole scene: first, that initial call from God and Abraham’s response, second, the way God describes Isaac, and, third, the reward that Abraham receives for his willingness to sacrifice. In turn, we can apply each of these to our lives, and consider how we respond to the sacrifices that God asks of us.

That initial call from God and Abraham’s response is the first thing that sticks out. “God put Abraham to the test,” we’re told, “and said to him: ‘Abraham!’ ‘Here I am!’ he replied.” Then God gives instructions on how Isaac is to be sacrificed. First, notice Abraham’s prompt reply: to the sound of his name, a personal call uttered only once, Abraham replies, “Here I am!” Contrast this to Adam and Eve, after the fall, when they hid out of shame, and God had to ask, “Where are you?” although He already knew they were far from Him because of sin. On the contrary, the one who really wants to do God’s will is prompt to reply, and that exclamation, “Here I am!” expresses a willingness to do anything, to go anywhere, and to give up anything. If we are to have truly generous hearts, we can’t set limits on what we will do for God; we can’t tell Him, “This far, but no farther.” We must trust in God; when He calls, and we see clearly what it is He asks of us, we should neither doubt nor hesitate. It’s interesting that God speaks to Abraham in the beginning, but the rest of the interactions that Abraham has with God are done through an angel; God speaks once, and then Abraham must walk the lonely road to the mountain by faith.

Regarding the second, God gives a very beautiful description of Isaac to Abraham: “Take your son Isaac, your only one, whom you love.” It would’ve been enough to say simply “Isaac,” but God emphasizes that Isaac is an “only son” and “beloved.” In other words, God emphasizes the difficulty of the sacrifice. He’s not asking for just any old sacrifice; He’s asking for something that hurts, something that is more precious to Abraham than anything else he has or possesses. He’s asking Abraham to sacrifice the child of the promise, the one he had waited so long for. When we give up sin, properly speaking, we’re not making a sacrifice; there is nothing sacrificial in ceasing to steal, or to lie, or to gossip. Rather, the word sacrifice comes from the Latin sacra, holy or sacred, and facere, to make.

When we make a sacrifice, we are taking something that is good, something we could have without sin, and offering it to God, taking a good thing and making it even better by giving it to the Almighty. Opportunities abound every day for making sacrifices: it might be as small as sacrificing my time in order to be with the sick or the elderly, or even simply to be patient with relatives or coworkers who annoy me; it might be sacrificing a snack or an outing and using that money for charity. However, it could also be something as great as sacrificing my dreams, my hopes, and what I want (or what I think I want) in order to give myself completely to God, be it in a vocation to religious life or priesthood, or to a spouse and family in marriage.

We shouldn’t think that God doesn’t know how hard it is, or how difficult it is to sacrifice. God knows, and He knows better than we do. In Matthew’s Gospel (19:27-30) Peter, speaking for the Apostles and, for all those who leave things to follow Christ, asks about the reward for those who give up everything, even the little they had: “We have given up everything and followed you. What will there be for us?” Notice the list of things that Jesus mentions giving up: “Everyone who has given up houses or brothers or sisters or father or mother or children or lands for the sake of my name will receive a hundred times more, and will inherit eternal life.”

This passage follows right after the rich young man had gone away sad because he had many material possessions, and it’s quite probable that Peter had his material goods in mind: his fishing boat, his house, and so on. The word Peter uses just means, “everything.” Yet, Jesus replies a specific list of things, the majority of which aren’t simply material goods, but, we could say, more spiritual. The list starts with material goods, namely, houses, then more spiritual ones, family members, and ends, oddly, with the Greek ἀγροὺς, meaning “fields” or “lands,” which would seem to be simply material. Yet, it’s important to remember that fields in the Bible aren’t simply physical places: they are part of a family’s inheritance and future, and fields are not only the place where things are planted and grown, but also where cattle can be raised, battles fought, and the dead buried. In other words, fields are full of potential, full of future possibilities and dreams. In our lives we surrender all that to Jesus, and it’s as though Jesus responds by saying, “I know exactly what you have given up for my sake, even more than you know”; indeed, He’s the only one who really knows. The God who tells us through Isaiah, “See, upon the palms of my hands I have written your name” (Is 49:16), and in the Psalm that “our tears are stored in His flask, recorded in His book?” (cf. Ps 56:9), will not let anything we give up be forgotten. He takes all of that, and opens to us a hundred more possibilities as He takes our futures into His hands: as He said through the prophet Jeremiah: “For I know well the plans I have in mind for you—plans for your welfare and not for woe, so as to give you a future of hope” (29:11).

Regarding the third, Abraham receives a great reward for his willingness to surrender everything to God. The book of Genesis presents us with a long list of rewards, but one, perhaps even greater reward, is missing. This reward is mentioned by Christ Himself in John’s Gospel (8:56): “Abraham your father rejoiced to see my day; he saw it and was glad.” Saint Ephrem comments that Abraham rejoiced when he saw the lamb caught in the bush, because he saw in it the future Lamb of God, who was to take away the sins of the world. In that moment, he caught a glimpse of the salvation that was to come, a time when yet another only-Begotten, Beloved Son would head to the summit of a mountain, but this time, that Son wouldn’t escape sacrifice. The rewards from God far outweigh the sacrifices we make for Him, because in them we can catch a glimpse of the reward that is to come. God is not outdone in generosity, and, although the sacrifice might be difficult, God always gives His grace, and “with dawn comes rejoicing.” Lest we forget, the evening of Abraham’s rejoicing probably started out as the worst morning of his life, as he led Isaac out into the middle of nowhere to kill him.

For us, then, we need to be prepared to give everything we have to God. Perhaps, as in the case of Abraham, it will be enough simply to offer it, even though our hearts might break. He might simply ask that we purify our attachment to things, and then leave them to us, with our hearts set on Him alone. Perhaps, though, God will ask that we do indeed surrender it to Him, sacrificing it to Him and His adorable will. What God wants is always what is truly best for us, and we must be convinced of this with the certainty of faith.

If we really want to be saints, then we must be willing to sacrifice everything for Him. What good does anything in this life do, if I’m not willing to give it to God. We can ask ourselves: what is God asking me to sacrifice to Him? What is it that He asks me to give to Him, or to Him through others? Where is my heart set? Where is my treasure? What holds me back from giving everything to God? Through the intercession of Mary, Our Lady of Sorrows, let us ask for the grace to have minds ready for sacrifice, and wills ready to leave everything to follow Christ.

Creator and Sub-Creator, part II

Are You the Gardener? A Lenten Reflection From a Priest of the Institute of the Incarnate Word

Lent: A Pathway Between Two Gardens

From a priest of the Institute of the Incarnate Word

We are now in the first week of Lent. In order to aid our passage through this important liturgical season, we offer weekly meditations. Each is written by a priest from the Institute of the Incarnate Word, IVE, and we are delighted that they have taken the time to do so. The first focuses on some general thoughts for Lent and is by Fr Brian Dinkel, Pastor of Our Lady of Peace in Santa Clara, CA. He writes:

With due reason, the archetypal setting for the Lenten season is the desert. The arid desolate land that purges us from the attachment to the comfortable life of sin, which goes no further than self-satisfaction. What about Gardens? As much as our senses and inclination to comfort may need some desert time for detachment, so too might our intellect and will need some time spent in the Gardens for conversion. Let us explain.

The Old Testament line that inaugurates Lent for most is: “Remember you are dust and unto dust, you shall return.” (Genesis 3:19) These words are spoken in a Garden, Eden. In this Garden, through an act of disobedience, Adam and Eve turned from God. This is followed by what Bl.John Henry Newman wittingly describes as “The original excuse.” (Cf., Bl. John Henry Newman, Oxford University Sermons, Sermon 8) First Adam points to Eve saying, “The woman whom you put here with me—she gave me fruit from the tree,” and then Eve places the onus on the serpent, saying, “the snake tricked me, so I ate it.” (Genesis 3,12-13) In another other Garden, Gethsemane, we witness a supreme act of obedience to the Father.

Jesus speaks to His Father with child-like simplicity: “Father, if Thou art willing, remove this cup from Me: nevertheless, not My will, but Thine, be done.” (Mt 26,42) In this Garden, however, He makes Himself the excuse for everyone else. The Garden of Eden is where life is springing forth on all sides, but selfishness leads to death. In Gethsemane, death is all-encompassing, but in this garden, selflessness leads to life.

His soul was sad to the point of death. He felt within His soul a sadness that was deep enough to cause the feeling of death. The Greek adjective περίλυπος (perilypos: from peri‐ around + lypé sorrow, grief) means properly, around‐sorrowful, that is, sorrowful all around, encompassed with sorrow; i.e. exceedingly sorrowful. (Cf., Mt 26,38) Therefore, the Jesus Christ, as St. Paul describes it, became sin, “for our sake he made him to be sin who did not know sin.” (2 Cor 5,21) The moral sufferings of Jesus were without comparison; they were tremendous; they were of greater suffering than the very nails that pierced His hands and His feet. It was so intense that He sweat blood. After all of this agony, He calls us into communion with Him this day. He gives us the blessing to be with Him, to receive Him, to be in communion with Him.

We have to look at, take ownership of, and reject what we have done. We must also acknowledge and cherish what He did, for me, in order for my heart to begin to change. One needs to see the darkness and evil of sin, that it is mine alone, and that Jesus – the Innocent Lamb – has taken it upon Himself to free me from them. As Pope St. John Paul taught, “Sin is an integral part of the truth about the human person. To recognize oneself as a sinner is the first and essential step in returning to the healing love of God.”

I need to see this, I need to look at this, in order for there to be real, lasting change; otherwise, I never see myself honestly, nor do I give the great price that Jesus paid for me an honest consideration. Our faith, religion, is more than pursuing happiness or self-realization – it is friendship and love. He took on a terrible amount of filth for me and He continues to call me like a loving friend who says: “forget about it – I don’t condemn you, I absolve you and forgive you, but go and sin no more.”

Our hearts must change. Ash will probably not do it, but maybe God—so meek and humble who came down from heaven, clothed Himself in our sins and poured forth blood from every pore of His body—will.

Here, in this Garden, Jesus places the sins of all human beings upon His shoulders. Thinking of the circumstances, the number, the malice, the ugliness, my own sins, . . . sins of a culture, of a society, of governments, our uncontrollable pride that in the name of liberty we unhinge ourselves from subjection and when faced with our ruin we place the blame on God who did not intervene or we reject Him altogether. He who knew no sin, placed upon himself all of this.

He can take away from these awful things something good – His Passion is our Redemption. He wanted to give us the sacraments. Therefore, no matter how bad our sins may be, or have been, God’s love is Greater – out of love for us He clothed Himself in this suffering. 2. Love – the love of God for each and every one of the members of His Mystical Body. Jesus saw all of His disciples, those who would follow Him, He also saw all of our infidelities. How we place our affections on material things, the insults that we make towards one another, the divisions, the hatred, the calumny, . . . He saw the lukewarmness and indifference of His friends.

He saw all of this, the martyrs of all times, the sufferings of the members of His body. He suffered these as if it were His own body. These were His members. The innocent ones who were forgotten or abused, thrown away by a society. For this reason, we know that Jesus suffered when we suffer. And this produces a profound suffering in His person. The Father in His infinite Love sent an angel to console Him, as His friends could not stay awake and watch one hour with Him.

Paintings are by Bosch, Goya, and Tiepolo respectively.

Florentine Street Shrines - Can We Do This Today? Will Today's Della Robbia Please Step Forward?

When I was studying portrait painting in Florence, several years ago, I was struck by the charm of the old street shrines that can be seen built into the walls of the buildings that line the narrow streets. Many date back to the time of the building itself.

Not all are still obviously the focus for prayer, many seemed to unnoticed in a city in which Renaissance art abounds and much of the population has fallen away from the Faith.

Since then I have wondered, from time to time, if this is something we could do today, in a time and in places where Catholicism is not the dominant faith and the driving force the culture?

My feeling is we might, in many instances, struggle to persuade local government to go along with such a thing. However, perhaps if done tastefully and discretely on private property that is visible from the public street it might be possible.

I suggest that if what is done is truly beautiful, even non-believers would want it and it would, to a large degree, disarm potential critics by removing their desire to be offended by outward signs of the Faith. I have a friend who runs a menswear shop in the UK and he always places a small icon of the face of Christ, a Mandylion, which is just 6' x 4' in size, low down on the wall behind the counter. While it is not an obviously bold statement of faith, he deliberately places in such a position that when people pay for their clothes, they will see it on the wall behind the till in such a way that it gives the impression that they are peeking into his personal space and seeing an image that is their for his private devotion. He says that nobody ever objected, and many asked about it.

Non-Christians (and for that matter many Christians too) are much more likely to be irritated if the art is ugly or sentimental. I have often wondered, for example, if the militant secularists are in fact doing us a favor by objecting to the kitsch shopping mall nativity scenes that seem to be standard issue for retailers nowadays. Perhaps they are the unwitting agents of the Holy Spirit? Before my conversion in my early thirties, piped carol music and brightly-colored plastic McChristmasses gave me the impression that Christianity was for saddoes who didn't even know that they ought to be embarrassed by being associated with this stuff. This did far more to put me off the Church than tales of Popes fathering illegitimate children or the brutality of the Teutonic Knights in the Baltic and the Middle East!

If we did decide to do this, what form should it take?

Well, here's an idea. I recently posted a photo of my first stab at creating an outdoor icon corner in a balcony garden.

I am hoping that as the plants grow through spring and summer that the hard edges will soften and overgrow, slightly the images. The paintings are prints that I obtained from a website selling them on rustic wooden planks, which I have varnished and screwed to the stool, which came from a consignment store.

A reader saw the photos and got in touch with me, suggesting that someone might like to start producing ceramic tiles with the standard core images of the icon corner - Our Lady on the left, the crucifixion in the center and the Risen Christ on the right which could then be set into the wall.

I do not know the economics of tile production but wouldn't it be wonderful if we could have beautiful triple sets of tiles? I imagine they might be something like the Della Robbia ceramics, except stylistically gothic or iconographic (just to suit my personal taste) and polychrome. Maybe in the form of a Jonathan Pageau relief carving!

Here is an original Della Robbia:

I once wrote a feature on my blog, thewayofbeauty.org, on how houses in southern Spain have tiles containing geometric patterns set into the walls of their houses - a Christianization of the Islamic cultural inheritance, here: Geometric Tile Patterns in Andalusia.

Perhaps we could have a combination of the two ideas in which we start to have simple icon-corner triple sets set into such patterns? If done well, it could the house prices up - even if you are selling to an atheist, I suggest!

Just a thought.

Creator and Sub-Creator, part I

A Young Nun Tells Us How Wearing the Habit Helps Her to Live Out Her Vocation

The habit provides us with a freedom which to the world seems a restriction.

The anonymous Sister who wrote these words is currently a student at www.Pontifex.University and she wrote them for an essay set for a class Final. She is one of the sisters of a community in Santa Rosa, California, called the Marian Sisters of Santa Rosa, and is a seamstress for the community. Her duties include making the community's habits. I asked her to describe why she felt this work was important, before going on to describe (in the next essay) how this informs her work in making the habits for the other Sisters.

The essay is entitled A Visible Witness; what struck me about it particularly were her anecdotes of personal reactions to the habit. She writes that it was seeing nuns wearing habits when she was a little girl that spoke to her of this “alternative” lifestyle (if I can use that phrase!) I found her accounts of the positive responses of ordinary people to her when they see the habit especially charming. For ease of reading, I have removed the footnotes and references from the original essay. The photograph below is taken from the community’s website.

She writes:

Early in the Church, those who dedicated their lives to God wore some form of identifiable clothing that distinguished them from the world. The purpose was to visibly set them apart from the world for God’s service. Through the centuries this type of clothing, namely the religious habit, has taken many shapes and forms in the diverse communities that God has called into being. During the past sixty years, the value, relevance, and need of the habit has been disputed. However, many young people with vocations to religious life are being drawn to communities that do wear the habit. It is my opinion that in our world today, this visible witness of the religious habit is still needed to silently but eloquently proclaim the reality, presence, and primacy of God.

One of the first references of any sort of garb for those who gave their lives to God is in the writings of St Pachomius, who founded the cenobitic way of life in the fourth century. In his Rule, he requires all those who pass the initial tests for entrance into the monastery to be stripped of their secular clothing and be clothed in the monastic habit. St Benedict and St John Cassian also prescribe the clothing in the habit in their Rules. St Augustine also refers to a plain and simple habit for both men and women religious. This new and different clothing was a symbol of renunciation of the world, and the simplicity and poverty of religious life. No monk was to have anything different than another so that there could be no cause for contention over material things. For women, the veil was also given as a special sign of consecration to Christ, their Divine Bridegroom. Since the time of St. Ambrose, there has been a special ceremony of conferring a veil on a virgin. The veil is also a public symbol of the nuptial union of Christ and His Church.

The religious habit was valued as the strong visible witness of a life given to God, and so continued as part of religious life. Religious habits remained simple, often in black, to signify the death to the world and to self that the religious life entails. Various parts of the habit, such as the scapular, were added as time went on, but the essentials of the tunic, belt, and veil, for women, remained consistent. St Benedict in his Rule refers to the scapular as being a garment worn for work. The scapular is a garment made of two long pieces of fabric, roughly the width of the person and the length of their height, joined together at the shoulders so that one piece falls in front and one in the back of the person. It was originally used as an apron, protecting the tunic while working. St Simon Stock and St Dominic were both given the scapular directly from Our Lady to become a regular part of the habit of their respective orders. At the end of the twelfth century, St Dominic saw a vision in which Mary held a scapular which was to be part of the Dominican habit. Around the same time, St Simon Stock received the Brown Scapular as a pledge of salvation for all who wear it and it has become a sign of Her protection of the soul. The scapular, as well as each part of the religious habit, took on a special meaning as the privilege of wearing the habit was better understood.

As different orders started in response to God’s call, each one assumed a distinctive habit that would distinguish the different orders from one another. Benedictines were known by their black habits, Dominicans wore white tunics and scapulars symbolizing purity, and Franciscans were recognized by their brown or gray robes for poverty. For women, the black veil was often a sign of profession, succeeding the white veil of a novice, usually worn over a white wimple which covered the head and neck of the sister. As more orders of sisters were founded, many interesting and distinctive forms of the habit, especially the veil, came into use. The front of the veil could be rounded or square, fit closely over the face, or widely fall over the shoulders. There were veils that had frills around the face, a box-like shape, or even a starched bow under the chin. Different colors were sometimes used, such as blue in honor of Our Lady. While retaining the essence of a garb set apart for God, each different community could be known by the sister’s particular habit.

In the 1950s, it was recognized that some of the parts of the religious habit, especially for women, had become overly complicated or impractical. Some communities used many yards of material in the tunic alone. The amount of material made it hard to wash frequently and expensive to make. Another example is the veils which came so far around the face that it eliminated the sisters’ peripheral vision. For sisters learning to drive a car, this would be dangerous. Pope Pius XII in 1951 commented on the need for a modification of the habit to suit the present needs.

Shortly after the Second Vatican Council, the topic of modifying the habit again was addressed and communities, in obedience to the Church, considered revising this aspect of their religious life. With all the other social issues going on in America, such as the radical feminist movement and concern for social justice, it seems that many American sisters interpreted the call for modification as permission to cease wearing the habit altogether. From my perspective, they thought in goodwill that for the sake of “equality” and “the liberation of women”, sisters now were not forced to wear such restrictive clothes that were remnants from unenlightened and past times. In some communities, this erroneous interpretation was held by sisters in authoritative positions, and so entire communities were deprived of the habit. This was not the case for all communities. Many did follow what the Church truly desired in simply modifying their habit in such a way that it retained its character as a clear, visible witness of Christ. In addition to these faithful communities, many new communities who wear the habit were started in America. The growing communities of sisters are those who do wear the habit because young women who hear the call to religious life recognize the need for it more than ever in our world today.

In the past 60 years, the Church has given much instruction on religious life, including the topic of the religious habit and its value. In the Code of Canon Law, it states that “Religious are to wear the habit of the institute, made according to the norm of proper law, as a sign of their consecration and as a witness of poverty” (669, §1). Pope St John Paul II explains the reason for this in his apostolic exhortation Vita Consecrata.

“The Church must always seek to make her presence visible in everyday life, especially in contemporary culture, which is often very secularized and yet sensitive to the language of signs. In this regard, the Church has a right to expect a significant contribution from consecrated persons, called as they are in every situation to bear clear witness that they belong to Christ.

Since the habit is a sign of consecration, poverty, and membership in a particular Religious family, I join the Fathers of the Synod in strongly recommending to men and women religious that they wear their proper habit, suitably adapted to the conditions of time and place”.

Other Church documents, including the Decree Perfectae Caritatis, reference the necessity of the habit and how it should be modified according to current needs. The Church recognizes and articulates that the habit is important. It provides the visible witness that Christ is first in our lives and that a religious strives to live completely in that reality. Wearing the habit exclusively declares that the religious do not worry about material things, and relies on God for all temporal needs. The simplicity and poverty of the religious life is manifested by having only one thing to wear, for everyday work as well as the most formal occasions. Even if a community’s habit needs to be modified for practical reasons or for the particular apostolate, it is still to be a clear sign of consecration to all, including the religious herself. The habit bears witness both to the reality of God, and that we are to be living and working solely for Him.

The habit is very connected to my vocation to the religious life. In the diocese of Santa Rosa where I grew up, there were a few sisters from three different communities ministering in the schools and the hospital. However, if I had not been told, I would not have known they were sisters because they did not wear a recognizable garb other than professional-looking clothes, a lapel pin, or cross necklace. Besides the saints who were religious, the other community of sisters I was most familiar with was the Poor Clares of Perpetual Adoration on EWTN. Wearing the full habit, they were an unmistakable witness of religious life. At age six or seven, I thought I was going to be a nun, which in my mind meant going to Alabama to that community. My sister and I would play that we were nuns and always wore fabric on our heads for a veil since we knew that was part of being a nun. Even at that young age, I had an intuitive sense that being a sister involved wearing a habit. The thought never even crossed my mind to be like the sisters in my diocese, since I just thought they were a different kind of sister and not the kind that I would want to join. After high school, when I was seriously discerning the religious life, the habit was a necessary component of any community I considered. If God was calling me to be a sister, I desired to look like one. The Marian Sisters of Santa Rosa, who had just come to the diocese, wore a beautiful habit of white and blue. There was no question of who they were since their clothes proclaimed that they belonged to God.

Since receiving the habit of the Marian Sisters of Santa Rosa, I am so grateful each morning to dress in this habit. The habit provides a freedom that to the world seems like a restriction. I am free from the worry of what to wear if it will be appropriate for the occasion, if the color suits me, or if it is modest enough. It takes much less time to get ready for the day when putting on the habit since there is no deliberation involved. When wearing secular clothes, one outfit is tried on, and then removed to try another, until, after much time and effort, a set of clothes is decided upon. Now, my time is used to beautify my soul for the reception of my Spouse in Holy Communion later that day. To the world, only having one choice might be seen as a lack of creative freedom to express my personality by what I wear. In my experience, never having other options of what to wear frees me from thinking so much about myself to think about the more important things in life. While donning the holy habit, I am praying, asking God for the strength for what I am to face that day, and clothing myself in His grace. Creativity is not suppressed but redirected away from myself to invent new ways of giving glory to God and showing love to Him and those around me. My personality, instead of being stifled by the habit, is revealed even more clearly through my actions and words because my clothes are not a distraction. Wearing the habit, I am free and even expected to pray in public, and to say “God bless you” to everyone because I am what I look like: totally dedicated to God.

When any of the sisters walk or go anywhere, we receive attention because of the habit. Some people spontaneously ask for prayers, intuitively trusting in our intercessory power with God. Others will relate stories of being educated by nuns, or share fond memories of an aunt who was a nun. Many comment on the beauty of the habit, happily surprised to see it after thinking it was a thing of the past. These are some of the responses we receive from those who come up to talk to us, but many more see us and are affected by the presence of God apparent in us, even from a distance. To travel to my apostolate, I walk for ten minutes along one of the busiest streets in the city. Hundreds of cars pass me each morning as I pray my Rosary. One day recently, I received the comment, “I saw you on the street corner, and thought how beautiful your outfit, or whatever you wear, is!”. It is not uncommon for a generous soul to anonymously pay for our meal, or grocery purchase, not because they have talked to us, but because they know who we are by the habit. Though we might never interact with those who see us, we pray that we are a channel of grace to bring them closer to God.

The habit, while being a sign of God’s Presence in the world, is also a reminder to the religious herself of who she is. In my experience, the habit aids recollection and prayer in times of formal prayer, as well as when going about my duties. The sides of our veil, coming over our shoulders, act as slight blinders to our peripheral vision, directing our focus straight ahead to God. Our habit is long, obliging us to move with care and Mary-like grace. When I am struggling, or need assistance with anything, I find my hand reaching up to clasp Our Lady on my Miraculous Medal. As a professed sister, I wear a ring, reminding me that I am Christ’s Bride before any role or duty I have in the apostolate. I know, whenever I am acting, that I act not as an individual, but as a representative of Christ, His Church, and our community. The respect or attention I receive from others is not for me as an individual, but on account of the habit, it is for Christ, whose bride I am and whom I reflect to the world.

The religious habit is the beautiful sign of consecration to God since the early Church. All who see it are reminded that there is a higher purpose in this life than the concerns of this world, that there is some reason, namely the love of God, that religious would dress in this way. The habit declares without words that this person has a strong relationship and intercessory power with God. The value of the witness of the habit is proved by its resurgence in the Church and will continue to be a clear manifestation of God to the world.

David Clayton on Annuciation Radio, 4 pm Monday,

I am appearing on Annunciation Radio - annunciatioradio.com - interviewed by Patricia Ode-Murray for the Virtuous Life show. It will be aired on Monday 4pm EST and posted on the website after that as a podcast, here. The topic is beauty and the culture, with a special interest in a formation in beauty as outlined in my book, the Way of Beauty and which is offered in the Pontifex University Master of Sacred Arts program

The Christian Artist – A vocation of service

Saints of the Roman Canon: St Agatha, February 5th

Today is the feast day of another of saints of the Roman Canon about whom we know very little beyond the fact of her existence and her martyrdom. Nevertheless, St Agatha is one of the most highly venerated virgin martyrs. By tradition, she died in the persecution of Decius in 251 AD.

According to tradition she suffered cruel torture, her breasts were pierced with pincers and she was healed by St Peter. Then she was then subjected to torture by hot coals and shards of glass until this was interrupted by the eruption of Mt Etna. Finally, she was sent back to prison where she died of starvation.

It is this gruesome death and the grace with which she faced it, that is reflected in the iconography of her. She is a young woman who carries severed breasts on a plate or has pincers. She sometimes displays a candle or flame, a symbol of her power against fire; a unicorn's horn - a symbol of her virginity; or a palm branch or cross - symbols of martyrdom. Many of the images from the Renaissance and Baroque periods graphically focus on some of these details in ways that might not appeal to modern sensibilities (or mine at any rate!).

The last painting is by Zurburan and the one before that by Piero Della Francesca - which is in my opinion very poor. This heartens me as it shows that even an artist as great as he was can have an off day!

This early Baroque painting, from 1614 by Giovanni Lanfranco is more tasteful, I feel, showing St Peter healing her injuries.

In the Eastern Church, she is known as St Agatha of Palermo and icons of her tend to show the generic symbols of martyrdom, the palm branch or cross.

This is one of a series of articles written to highlight the great feasts and the saints of the Roman Canon. All are connected to a single opening essay, in which I set out principles by which we might create a canon of art for Roman Rite churches, and a schema that would guide the placement of such images in a church. (Read it here.) In these, I plan to cover the key elements of images of the Saints of the Roman Canon - Eucharistic Prayer I - and the major feasts of the year. I have created the tag Canon of Art for Roman Rite to group these together, should any be interested in seeing these articles as they accumulate. For the fullest presentation of the principles of sacred art for the liturgy, take the Master’s of Sacred Arts, www.Pontifex.University.

Where Can Catholics Learn to Paint or Carve Icons? Go to Hexaemeron.org

I am often asked for recommendations of classes that would be good for Catholics to learn traditional iconography. One place to consider is Hexaemeron.org which has just announced the first of its icon painting and icon carving courses for 2018. They are now taking students for their 'Six Days of Creation' integrated series of workshops for different levels of experience. Go to their site for more details.

Furthermore, you can earn credit on these classes from Pontifex University that would be recognized as part of studio requirement of their Master of Sacred Arts degree. Again, details can be found at Hexaemeron.org and www.Pontifex.University.

Hexaemeron.org a non-profit based in the US which was founded in 2003 which offers short courses and workshops in a variety of locations around the world but has its main focus in North America. It is founded by Orthodox Christians and is welcoming and respectful to Roman and Byzantine Catholics.

All their classes in painting, carving and embroidery are always of the highest quality and the work of two of their teachers has been featured in the past on this site. Some readers will be familiar with painter Marek Czarnecki, who is Catholic. I wrote about two icons of Western saints that he painted for Our Lady of the Mountains, in Jasper Georgia, here.

Here is his Saint Cecilia:

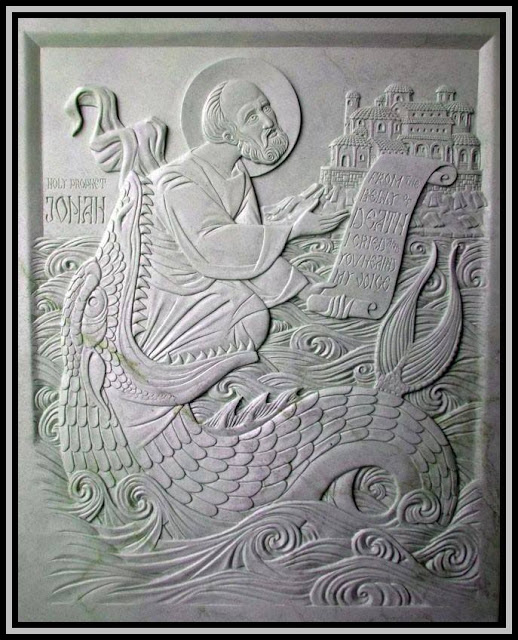

Another teacher that readers may be familiar with is the Canadian icon carver, Jonathan Pageau. Here is his icon of Jonah.

A New Blog on Catholic Culture and Beauty by Pontifex U. Professor, Dr Carrie Gress

Carrie Gress is at once a mother, journalist and writer, and a philosopher who specializes in beauty and aesthetics and studied Jacques Maritain for her doctorate.With such a wide range of interests, all of which are integrated with her faith, I would say she was a Renaissance lady if I wasn't somewhat negative on Renaissance culture! So, how about baroque lady instead?

Saints of the Roman Canon, St Agnes (January 21st), The 'Lamb' of God

This, past Sunday, January 21st, was the Feast of St Agnes. Early and Eastern images portray Agnes without attributes, and even as late as this 9th-century Roman mosaic, she is pictured as simply a generic virgin martyr (see example). But as early as the 6th century she begins to be portrayed with a lamb.

The Artist Lives for Christ

"He who does Christ's work, must stay with Christ always."

One of the greatest Christian artists is Giovanni Fiesole, better known to the world as Blessed Fra Angelico, the "Angelic Brother." Fra Angelico is a patron saint for artists. His style of painting beautifully bridges the iconographic and gothic traditions. Giorgio Vasari, author of "Lives of the Artists," referred to Angelico as a "rare and perfect talent."

A One-Minute Daily Spiritual Exercise for Cultivating Faith, Joy, Gratitude, an Ability to Apprehend Beauty...and It Might Even Be a Treatment for ADHD!

Try it for 30 days, and if you don't like it, we'll return you misery with interest!

Here's a quick and simple exercise I have been doing daily for nearly 30 years and it has brought such spectacularly positive results in my life that have accumulated steadily and incrementally ever since I started.

Every day, I jot down on a scrap of paper a 'gratitude list'.

The gratitude list is a list of good and beautiful things that have been given to me today for which I offer thanks to God. I put down the 'essentials' of life that are true for today, for example, I am alive, I have a bed to sleep in today, I have somewhere to live, food for today, clothes to wear and so on. I then put down all the little events specific to that day that go beyond what is necessary for life, you might call these 'luxuries', for example, sunshine on this January day (sorry New Hampshire), a kind word here, the relationships with others that I have and so on.

Actually writing the list is important - it forces me to crystallize the thought in my mind that much more concretely and makes the exercise more powerful. So nice thoughts in the shower, or on my morning walk don't count. It's not that there's anything wrong with that but it doesn't work as well for this exercise. I reach for pen and paper.

Also, I don't wait to feel grateful before I put them down - I write down what I ought to feel grateful for! The idea is that this exercise changes how we feel, and we grow in gratitude over time even if we don't start out that way. So right now I am grateful for a huge cup of steaming coffee! Fantastic!

Then I go further, I write down the bad things happening in my day and thank God for those too.

It may sound perverse, but this is powerful for turning around my attitude to what is happening to me. I believe that all that is good comes from God and that once we hand ourselves over to his protection and care he will look after us. While it is undeniable that there is evil and suffering in the world, these things to do not come from God, for a God that is all good cannot be the creator of something bad. Rather, he permits bad things to occur in order that a greater good can come out of them.

For this reason, I make a point of putting down negatives and disappointments of the day on the gratitude list too, knowing that a greater good must be coming out of it (even if I can’t see it yet). The realization of this helps me to deal with adversity with dignity and when I praise God for them (as St Peter tells us to do in one of his first letters) it helps me actually to feel good about them.

I look to the example of the saints for inspiration, including that of St Peter himself, who dealt with greater suffering than I have ever had and praised God for it. So I can say to myself, okay, it's pretty bad that I missed my train...but I'm not being crucified or stoned to death as St Stephen was. The account of St Stephen in Acts shows us that hope in God transcends all suffering if we can follow the promptings of God's grace. This exercise helps me to move that ideal incrementally.

Furthermore developing the habit of seeing minor irritations in this way is invaluable when more serious things happen to me. I have not had to face stoning or torture in a concentration camp, but in 30 years I have experienced some genuinely bad things - arising from the malice of others, my own selfishness or foolishness - or just plain bad luck. Having practised an attitude of faith and hope that transcends the small reversals on the regular basis, it is easier to see that what is true for the little things is just as true for serious disappointment and suffering. It has to be so. After all, if it's not true for the big things too, then it's not true at all. This exercise helps me to feel what I know intellectually to be true.

People can go on the gratitude list too: those we love...AND those we don't! If I have a resentment against a person, I put the person I don't like down and pray for that person too. Once written down I then pray repeatedly until I feel better, 'Please give X%#F&! everything I would wish for myself'. Sometimes it is through gritted teeth I can tell you! The more I dislike the person, the better things I ask for them. It might even be...(take your pick)...

Also, this is an exercise that can help us to enjoy what is beautiful. I am not by nature given to gratitude and can tend to take good and beautiful things for granted very quickly. So in my day, I especially look for beautiful things in the context of what might otherwise seem bad. I work on the principle that if I start to notice the little things, then it develops my appreciation for the grand vista too. One of the attributes of beauty is due proportion. If I develop the habit of noticing the parts and the details, then it helps me to see the good of the whole too. In other words, it helps me both to analyse and synthesize. These are skills that contribute to my ability to apprehend beauty - to see the part in relation to the whole, and the whole in relation to others. I suggest that every creative artist should develop this habit as part of his formation!

The dynamic of analysis and synthesis can be applied to time as well as space. In every moment there is something good happening, even if my general response to what is going on is initially bad. This how I can stop a few hurtful words before lunch influencing my sense that I am 'having a bad day', and instead allow the good to characterize the day. This is not only a better attitude to have, it is in accord with what is true. We know the day is good, objectively, because it is made by God and it is a gift given to all of us. This exercise allows us to feel what we know to be true in this regard. This is a similar frame of mind to what modern new-age therapy calls 'mindfulness' except, I would say, this runs deeper and truer. And it has a longer and broader pedigree coming out of traditional Christian mysticism.

So abandon this...

and focus more on being like the dog who waits expectantly for the crumbs from his Master's table, or alert to every murmur of his master's voice...

And this is why I say it could be an exercise that develops better concentration and attention to detail. I have wondered at times if, judged by my natural levels of concentration, I could be diagnosed with low-level ADHD. Certainly, I struggle more than I would like to concentrate on anything I'm not hugely interested in and would always rather listen to the talking book while driving the car than read it just because I can't sit still. I don't read fiction and haven't read a novel in years apart from easy-read detective stories. I like getting news in 5-minute podcasts and can hardly focus on a newspaper. I don't know how this compares with the norm for the population (and I have often wondered if it's down to all the coffee I drink) but regardless, this exercise does help to at least to get some things done and to enjoy the process as well.

It's not always a bad thing. I like squirrels and I'd rather be looking at a squirrel than contemplating my poor powers of concentration anyway. Joking aside, I know there are many whose lives really are made extremely difficult by a chronic inability to stay focused. Even so, I wonder though if a daily meditation of this type might help even those who are genuinely ADHD? It can't do any harm. And it is a task that needs very little attention time in itself. It takes me a minute or two at most to do this. The effect is cumulative - I was told initially to try it for 30 days and see how I felt at the end of that time.

So, I encourage to try it yourself and see how it goes. Remember, the Divine is in the detail!

Some of you may wonder what prompted my starting this habit nearly 30 years ago? The answer is that I met someone, an elderly man called David, who told me something that shook me when I heard it - misery is optional. When I heard it, my first reaction was to be certain he was wrong. I was certain because I was miserable, and if he was right, I would have to admit some terrible truths. First of these was that David knew more about how to live happily than I did; the second was that I was responsible for my unhappiness. My pride was such that I couldn't possibly admit either of these things easily.

Prior to meeting David, if I met a happy person the only way I could reconcile my misery and intellectual pride with their joy was to assume they were deluded or foolish, and probably both. Happiness, I had always thought, is the preserve of the stupid and superficial thinkers. When you are deep thinking and intelligent like me then you understand the profound truth that life is miserable. But David opened my mind by presenting me with a version of Pascal's wager (although I didn't realise that this is what he was doing), he challenged me to try it.

I had met David through a mutual friend who had invited me to coffee on the King's Road, in Chelsea when I was living in London. (It was a restaurant called Picasso's - I don't know if it's still around.) David was talking to my friend when he said this provocative statement, but when I heard him say it, I felt I had to intervene. In my unhappiness, I was one of those people who was so irritated and envious of happy people that I considered it a service to explain to them how deluded they were. So I interrupted and began to explain to him that although he might think he was happy, in fact, he was really unhappy (absurd as this sounds). David let me speak for a while, as I tried to reconcile the irreconcilable, and then cheerily stopped me: 'Please yourself, lad,' he said. 'But why don't you try the theory out?'

My friend then chimed in and said he had been doing a simple program of daily prayer and meditation that David had suggested to him and this had changed his outlook dramatically and encourage me to do the same. It was this personal recommendation from someone I liked that made me pause.

David told me he would happily show me these things too if I was interested. 'Try it for 30 days, do everything I suggest, and if you don't like it we'll return your misery with interest!' he said. The process that he gave me was called the Vision for You process. It was a daily routine of prayer, meditation, contemplative prayer and good works that are both simple and practical and involved about 10 minutes a day, plus a weekly voluntary commitment of service anywhere where I could be of use. I decided that it couldn't do any harm to try and he wasn't asking for money, so I thought I'd give it a go.

Something that persuaded me was that I had noticed a change in the positive in my friend, I thought, in recent weeks. He had started to become irritatingly cheerful and couldn't be.

The gratitude list is just one of the simple spiritual exercises he gave me and I would say that without a doubt it works. I can't prove it, of course, but I am convinced enough by it to have kept going with it daily for a long time. Another one of the exercises he gave me was to get on my knees in prayer every day and ask God to look after me so that I could give glory to Him and be of service to my fellows. As David said to me all those years ago put it, the gratitude list is written proof that when you asked God to look after you today, he answered your prayers.

Not that I saw it that way initially. David wrote my first gratitude list for me because I didn't really feel grateful for anything. So he took pen and paper and asked me, you are alive today aren't you? He waited for me to say, 'Yes' and then wrote it down. 'And you have clothes to wear?' Again he waited for me to agree to each item so that I confirmed that what was going down was true. 'And food to eat, for today at least?'...and a roof over my head? And a bed to sleep in? When I had agreed to each item as being true for me, he paused and said, 'You are now ahead of billions of people in the world who don't know where their next meal is coming from. Here is the evidence that the day is good. You have no good reason for complaint.'

David told me that this whole process, the Vision for You, would do more than raise my baseline of misery. It would give me a life 'beyond my wildest dreams', engender a deeper faith in God and help me to discern and realise my personal vocation. Some of you may remember a post from a long time ago in which I described how I became an artist. It is here - Discerning My Vocation as an Artist. David is the man I was talking about in this earlier article. He showed me how to be doing what I do now! It is also the process that converted me to Catholicism, and David was my sponsor when I was received into the Church in 1993 nearly five years later. Sadly he died of a heart attack in 1998 - nearly 20 years ago now. I would have loved him to see just how much this process, which I still practice to this day, continues to give me so much in my life and in the lives of people that I have passed this on to over this period. There are dozens.

I don't have the space to describe the full process here - I have a book manuscript ready for publishing which is over 200 pages long and which describes the whole story in detail. Once I had the initial daily routine as a habit and I decided that it was working, David introduced me to a series of deeper structured reflections and it was at these that included the discernment process. All in all, it took several months. It was work, but it was worth it!

David said that he would give freely of his time and consideration, but only on condition that if I benefited from it, I would be prepared to pass it on, in turn, to any others who wanted what was on offer. This is why I am happy to help anyone who is interested in following this process today if they are serious about doing it. If you have questions about it, do feel free to contact me, but in the meantime here is a document which contains a summary of the process, the spiritual exercises, the daily routine and the discernment process.

Master of Sacred Arts at www.Pontifex.University - a cultural, intellectual and spiritual formation in beauty and creativity for artists, patrons of the arts, and anyone who wants to contribute creatively to the establishment of a culture of beauty today.

Christ in the Realm of the Dead, by Joakim Skovgaard, 1891, 'the Danish William Blake'!

"Style and content are both critical if we are to portray the human form with dignity. It's not just what we paint, but how we paint it." "The Master of Sacred Arts program of www.Pontifex.University discusses in great depth how this consideration of the way in which we paint the human figure has influenced profoundly all the great Christian styles of art."

Here is the latest video presentation, by Bill Donaghy of the Theology of the Body Institute in Philadelphia, recorded just after the Easter Triduum last year. He discusses Christ in the Realm of the Dead, painted between 1891-94 painted by the Danish artist Joakim Skovgaard (1856-1933).

I did not know anything about this artist until I saw Bill's talk. Although not so obviously drawing on the Greek ideal, his style does remind me, in many ways, of William Blake. The dramatic touch in composition, the coloration look similar. And just like Blake he does not conform to the academic styles that dominated in the period that he painted.

While Christian artists are not bound to follow traditional styles (although I would argue they would need good reasons to depart from them) they must consider a style that has the right balance of naturalism and idealization. This is especially important when portraying the human form nude. Style and content are both critical if we are to portray the human form with dignity! It's not just what we paint, but how we paint it.This artist has created a work of great power without being prurient. He chooses poses that avoid revealing private parts - this is especially appropriate if portraying fallen man, for they are meant to be private in him more than in any other anthropological state. That is why we wear clothes - or we ought to - in most situations!

The drama of this moment which indicates, as Bill tells us in his commentary, 'where Adam fails Christ succeeds'.

https://youtu.be/5l19GX6dls8

The Master of Sacred Arts program of www.Pontifex.University discusses in great depth how this consideration of the way in which we paint the human figure has influenced profoundly all the great Christian styles of art.

Pontifex University is an online university offering a Master’s Degree in Sacred Arts. For more information visit the website at www.pontifex.university

Why Paint? Art is Not for Art's Sake, for God's Sake!

Mother Teresa of Calcutta used to say that “the money in your pocket is not yours, it belongs to God.” The same is true of all the gifts you have received.

By Deacon Lawrence Klimecki; this article originally appeared at www.DeaconLawrence.org

What is the purpose of artistic talent?

I am sure most, if not all of us, are familiar with the opening of a movie produced by MGM Studios. It depicts a roaring lion surrounded by the words "Ars Gratia Artis." This is the Latin translation of the phrase "art for art's sake."

"Art for Art's Sake" is a phrase coined about 200 years ago to express a philosophy that the true value of art lies in the art itself; that art should be divorced from any instructive, moral, or useful function. In other words, "true art" serves only itself.

But for the thousands of years prior to the early 19th century, art served a purpose, it served the community. For the Christian artist, art was and still is, a way to teach, promote Christian morals and values, and serve the common good. And because we share in God's creative force as sub-creators, we find an endless number of ways to accomplish that.

Mother Teresa of Calcutta used to say that “the money in your pocket is not yours, it belongs to God.” The same is true of all the gifts you have received. They have been given to you by the Holy Spirit to bring the world back to God.

Saint Luke’s account of the multiplication of the loaves and fish gives us an interesting example. It is not difficult to understand the apostle’s point of view. They brought barely enough food for themselves, let alone the thousands who came to hear the Lord. But rather than send them away Jesus told the apostles to feed the multitude from their own small stores. We can easily imagine some reluctance to give up what little they have. But because it is the Lord who asks they do so. And Jesus takes what they have, multiplies it, and not only is there enough to feed the thousands but there is enough left over to fill twelve baskets, one for each of the twelve apostles.

God asks us to return to Him what He has given us, in order that He may give us even more.

What are your talents and how are you using them?

There is a saying that your talent is God’s gift to you, what you do with it is your gift to God.

It is easy to use our gifts selfishly, and keep them to ourselves. For artists this may lead to the “ivory tower” mentality that no one can tell you what to do, you must follow your “muse.” That is art for art’s sake.

Our gifts were not given to us to indulge in own private whims, they were given to us to help feed the children of God. “Art for art’s sake,” is a lie that feeds into our ego. It seduces us into thinking we can make our own way without acknowledging the source of that artistic ability.

"The Parable of the Talents" teaches that we will one day be called to give an account of our stewardship over the riches we have been given. Will you be ready when that day comes?

______________________________________

Pontifex University is an online university offering a Master’s Degree in Sacred Arts. For more information visit the website at www.pontifex.university

Lawrence Klimecki is a deacon in the Diocese of Sacramento. He is a public speaker, writer, and artist, reflecting on the intersection of art and faith and the spiritual “hero’s journey” that is part of every person’s life. He maintains a blog at www.DeaconLawrence.org

The Holy Name of Jesus!

Saints of the Roman Canon - Abel the Just, January 2nd (EF), Dec 24 (OF)

Abel, the son of Adam is mentioned in the Canon of the Mass as Abel the Just. It hasn't been easy to confirm, but my best information is that his feast day is January 2nd for the Extraordinary Form Calendar and I was just informed (H/T Sequoia S) that it is December 24 for the Ordinary Form calendar. His story is in the book of Genesis. You may remember his offering, a sacrificial lamb, was appropriate, which that of his brother Cain was deficient. When Cain's offering was rejected, Cain murdered Able out of jealousy. He is a hugely important figure liturgically in that his story is one that helps to establish the pattern of religious life for us, with worship and sacrifice at its heart. This is true, broadly speaking for the patriarchs, and specifically, he is often associated in this regard with Melchizedek and Abraham. I have covered both of these figures in previous postings and any who have read those will remember the mosaic from Ravenna which has the three together.

This importance is made real, by the continued references to him in the Old Testament, as well as in the Mass, of course. Here is an excerpt from the Catholic Encyclopedia:

In the New Testament Abel is often mentioned. His pastoral life, his sacrifice, his holiness, his tragic death made him a striking type of Our Divine Saviour. His just works are referred to in 1 John 3:12; he is canonized by Christ himself (Matthew 23:34-35) as the first of the long line of prophets martyred for justice' sake. He prophesied not by word, but by his sacrifice, of which he knew by revelation the typical meaning (Vigouroux); and also by his death (City of God XV.18). In Hebrews 12:24, his death is mentioned, and the contrast between his blood and that of Christ is shown. The latter calls not for vengeance, but for mercy and pardon. Abel, though dead, speaketh (Hebrews 11:4), Deo per merita, hominibus per exemplum (Piconio), i.e. to God by his merits, to men by his example.

The Ghent Altarpiece portrays this so beautifully, by connecting the two images of Abel and Cain with the fallen Adam and Eve (who have deep shadows associated with their images and who are naked, but ashamed of their nudity).

Here is an early gothic illumination, which again puts to the two important parts of the 'Kayn' and Abel biblical narrative together.

Later images, especially, Renaissance and baroque images tend to focus more on the drama of the murder, emphasizing the effects of the Fall. This is important, of course, but personally, I would like to see this aspect of offering and worship brought to our minds too, especially for images in church. Here is Titian's wonderful painting from the 16th century:

This one by an anonymous 17th-century artist does have an indication of the sacrificial altar that is just a little more obvious than Titian's.

Here is William Blake's depiction, typically idiosyncratic! He focusses on the expulsion of Cain 'East of Eden'.

This is one of a series of articles written to highlight the great feasts and the saints of the Roman Canon. All are connected to a single opening essay, in which I set out principles by which we might create a canon of art for Roman Rite churches, and a schema that would guide the placement of such images in a church. (Read it here.) In these, I plan to cover the key elements of images of the Saints of the Roman Canon - Eucharistic Prayer I - and the major feasts of the year. I have created the tag Canon of Art for Roman Rite to group these together, should any be interested in seeing these articles as they accumulate. For the fullest presentation of the principles of sacred art for the liturgy, take the Master’s of Sacred Arts, www.Pontifex.University.