Companionship is also one of the greatest blessings we receive when we receive the precious Body and Blood.

The Martyrdom of St Lawrence, by Antonio Campi

Today is the commemoration of the martyrdom of St Lawrence, who died in the persecution of Emperor Valerian in AD 258.

TThis picture was painted by the Italian Antonio Campi and completed in 1581. Stylistically it belongs to what is called the Mannerist period. This runs from the period of the Council of Trent until about the end of the 16th century. Artists were searching for a new Christian harmonization of idealism and naturalism that was not necessarily so slavishly attached to the classical ideal of ancient Greece and Rome, as typified by the High Renaissance masters such as Michelangelo or Raphael, although some still chose to do so. It produced a variety of individual styles, some of which in my opinion had great merit and beauty, such as the paintings of Pontormo and El Greco, but most did not inspire followers. Hence we did not see the emergence of any coherent tradition that could fulfill the directives of the Council as part of the Counter-reformation, until the end of the century. This tradition became what we now call the baroque style and the pioneers were, Titian, lesser-known (today) Francesco Barocci who died in 1612, and the great popularizer of this new style, possibly named after Barocci, Caravaggio.

I chose this painting because it shows the gruesome death of this great martyr on a grid iron. We live in a time more than any other in the recent past of persecution of Christian. In the US it is still a soft persecution (although it may yet become a more violent persecution that involves physical danger, and what Christians in Pakistan, for example, face daily. Nevertheless, I feel the pressure to witness the Faith daily and I pray for the grace the courage to do so (and am dismayed at how easily I hesitate to speak up). Part of the inspiration for me is the courage of these great saints of the past, who stood up to the greatest of tests so heroically.

Some artists stuck more closely to the classical ideal than others. Pontormo's is one who continued to draw heavily to the classical ideal. He painted a picture of the Martyrdom of Saint Lawrence, now lost. Here is one by his student Bronzini:

Judas, Peter, and the Jordan Management Consultants

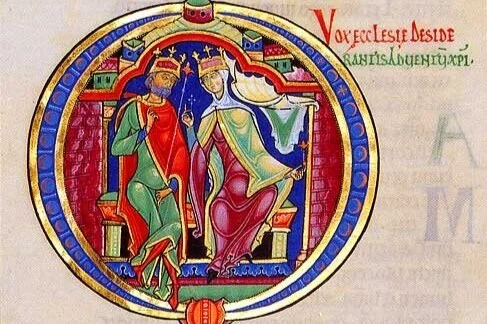

Pictorial Allegories of the Love of God Inspired by the Song of Songs - Part 3

A Whittler, Fish, and Our Meager Gifts

Pictorial Allegories of the Love of God Inspired by the Song of Songs - Part 2

The Devil, Naked Truth, and Abraham Lincoln

Pictorial Allegories of the Love of God Inspired by the Song of Songs - Part 1

Football, Rejection, and Failure

A Classic Book on Art and Beauty to Be Republished: The Beauty of Holiness and the Holiness of Beauty

The Camel, the Space Opera, and the Miraculous

How the Core of the Imagery in Your Domestic Church Should Be Different From the Parish Church

In the book (co-written with Leila Lawler) called The Little Oratory, we describe the traditional layout for images at the core of those in an icon corner or domestic church. The schema is as follows: Our Lady with Our Lord on the left, Christ on the Cross in the center, and the Risen Christ (a Mandylion, Christ in Majesty or Blessing Christ, for example, on the right).

The one above uses traditional iconographical art. Although it is called an icon (or 'image') corner it doesn't have to be icons. A standing crucifix and art in any of the Western traditional styles will work just as well. The logic as that we have a summary of salvation history symbolized here: the historical Christ on the left, with his mother from whom he was given his humanity, then the passion and death of Our Lord, and then Christ in heaven. We live with him, die with him and are raised up with him by 'putting on Christ' as St Paul refers to it in Galatians, through baptism, confirmation, and communion.

I first found about this when I read a book called Earthen Vessels - The Practice of Personal Prayer According to Patristic Tradition written by Gabriel Bunge who was a Swiss Benedictine monk. I had always assumed that this should be the basic layout in our parish churches too. To a certain extent, this is correct. However, I noticed that even in Eastern Rite/Byzantine Catholic churches, which are typically more concerned about following this tradition than Roman Catholic churches, the schema is not always followed precisely. Sometimes, in the icon screen, the central cross is absent, or if it is there at all it is tiny, barely noticeable and sometimes even with Christ not present on the cross.

I had often wondered why, given the evident importance of the passion, which it seemed to be downplayed so much. Recently it was explained to me. When the Royal Doors are opened for Divine Liturgy the altar will be visible and the liturgy will be taking place.

The death and resurrection is being played out in front of us, in other words, the transitionary events that link the left image to the right are happening before our eyes. The altar represents not just the place of sacrifice but the body of Christ being sacrificed too.

In the Roman Rite, we have more of a tradition of churches with crucifixions of course, but if done well this can be used to reinforce our understanding of what is happening in front of us. If the crucifixion is placed so to as to connect very obviously and visually with the celebration of Mass at the altar, the same message is communicated.

What we are seeing here is that both Rites are concerned with the communication of the importance of the Passion visually, but choose to emphasize its importance in different ways.

In the domestic church, there is no celebration to observe, we are the ones praying the liturgy so there is great merit to having a crucifixion prominently placed.

Ron Gaudio's blogpost on Pythagoras and his lasting influence on Western Civilization

For Pythagoras and many other Greek philosophers, the beauty of the cosmos reflected not only a harmonious order but divinity itself. That is why they were also a community that worshipped. Pythagoras’s legacy reached even to the United States, being responsible for the architectural beauty of Monticello, Harvard Hall, and the Capitol Building.