Our own sense of who and what we are is based upon the relationships we have with others. If you go around a group of people and ask them to describe themselves, apart from their name they will talk about themselves in terms of their relationships with others: for example, ‘I work with this company’, ‘I am a father and I have three children’. This is the essence of a person, as distinct from an individual. A human person is always in relation with others, starting from birth. No one, by choice, disengages from society altogether (not even a hermit) and is happy.

This understanding of the human person has a profound effect on how we view what society is. A relationship of the sort we are now envisioning is always between two subjects, that is two people freely cooperating as moral agents. This is termed covenantal and is based upon mutual self-sacrifice on behalf of the other - love. This freedom to respond as a person is one of the essential elements of society. Society therefore is the vector sum of the relationships within it. It is not a collective of self-contained individuals.

Our own sense of who and what we are is based upon the relationships we have with others. If you go around a group of people and ask them to describe themselves, apart from their name they will talk about themselves in terms of their relationships with others: for example, ‘I work with this company’, ‘I am a father and I have three children’. This is the essence of a person, as distinct from an individual. A human person is always in relation with others, starting from birth. No one, by choice, disengages from society altogether (not even a hermit) and is happy.

This understanding of the human person has a profound effect on how we view what society is. A relationship of the sort we are now envisioning is always between two subjects, that is two people freely cooperating as moral agents. This is termed covenantal and is based upon mutual self-sacrifice on behalf of the other - love. This freedom to respond as a person is one of the essential elements of society. Society therefore is the vector sum of the relationships within it. It is not a collective of self-contained individuals.

A human relationship is an entity in itself. Two people create, through the properly ordered love between them, a relationship that is distinct from each person, and does not destroy either’s integrity.

It is analogous, I think, to a chord created by two notes played simultaneously. We perceive the chord as something distinct created by the proximity of two notes, but the integrity of each note is not diminished by it. Something has been created out of nothing. This creation out of nothing is ‘superabundance’; love is always superabundantly fruitful (an example is the creation of the third person in a family). A loving relationship is created out of the harmony that exists between two hearts when each acts for the good of the other. There is a song (by U2 I think) that describes love as two hearts beating ‘as one’. In fact it might be more accurate to say that when love is present, two hearts beat not as one, but as three.

It is analogous, I think, to a chord created by two notes played simultaneously. We perceive the chord as something distinct created by the proximity of two notes, but the integrity of each note is not diminished by it. Something has been created out of nothing. This creation out of nothing is ‘superabundance’; love is always superabundantly fruitful (an example is the creation of the third person in a family). A loving relationship is created out of the harmony that exists between two hearts when each acts for the good of the other. There is a song (by U2 I think) that describes love as two hearts beating ‘as one’. In fact it might be more accurate to say that when love is present, two hearts beat not as one, but as three.

By using the word ‘love’ I do not always have in mind profoundly deep relationships. Any relationship, however casual, can reflect a motive for the good of the other. Even a cheery hello to a shopkeeper can reflect either a loving or self-centred motive. This means that whatever I do I bring to the party, so to speak, an aspect of every relationship that I have. I represent to some degree every community of which I am part – family, work, parish, tennis club and so on.

Liturgical activity is an act of love, in which I participate in the sacrifice made by Christ for all humanity. In participation of this supreme act of love is a transforming experience that by degrees changes me and makes me a better lover (and God knows, there is much room for improvement). This means that through every relationship I have, every other person and community with whom I relate benefits profoundly from my participation. Participation in the liturgy is a sacrifice of love their behalf. The effect is through what one hopes subsequently might be a more loving direct interactions with each person; but also because I am transformed through this participation, the relationship that exists between us and my prayers and intentions for them in the liturgy facilitate a supernatural transformation to the same degree and through my intentions for those people in the liturgy.

The liturgy therefore is the binding principle of society and those communities in which I participate. Family, friends, parish, Church, workplace, living quarters, country – will all benefit from my participation in the liturgy. This is so even when I am the only person who is doing this and no one else knows of my participation. When I go to Mass or pray the liturgy of the hours, I try to remember to consciously dedicate that day’s prayer to all those groups and individuals with whom I relate.

The liturgy therefore is the binding principle of society and those communities in which I participate. Family, friends, parish, Church, workplace, living quarters, country – will all benefit from my participation in the liturgy. This is so even when I am the only person who is doing this and no one else knows of my participation. When I go to Mass or pray the liturgy of the hours, I try to remember to consciously dedicate that day’s prayer to all those groups and individuals with whom I relate.

There is a maxim that the family that prays together, prays together. In the encyclical Marialis Cultus (On the Right Ordering and Development of Devotion to the Blessed Virgin Mary), as well as describing how praying with Christ in the Liturgy is the fullest expression of devotion to Mary, Paul VI calls the Liturgy of the Hours the 'highpoint which family prayer can reach'.(54)

By extension, I suggest, this is true for all communities. The benefit of this liturgical participation in the sacrifice of Christ is magnified if the community prays in community. Unless its raison d’être is communal prayer it is rare that in any community every single member can or would even want to pray regularly with his fellows. But by degrees it is possible to move towards this ideal anywhere. If practicalities allow (and we must be aware that often they will not) a visible posting of regular times that the Liturgy of the Hours is prayed with an invitation for any member to join, would invoke the public nature of liturgy. If that invitation extends to the general public to attend the community prayer, the better still. At Thomas More College we are lucky to have priests who can say daily Mass; in addition a core of devotees to the Liturgy of the Hours have organized a rota by which we do our best to ensure that two or three of us at least pray Lauds and Vespers each day for the community.

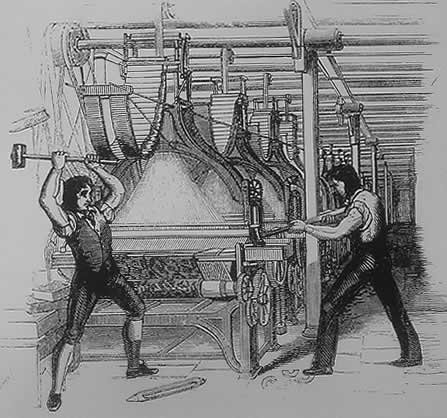

Culture reflects the cult that is at the core of it. However modest the fulfilment of this ideal, this is the means by which the culture of community or organization can be transformed to a Catholic culture that will be in harmony with all other institutions and social groups and work for the common good. It is no surprise, therefore, that any organization, such as many businesses which typically give no thought to liturgical piety at all, reflect a secular culture. So much so, that it doesn’t even occur to many people that the workplace can be or can even aspire to be a community. Consequently it is taken for granted that while it might contribute to the financial support of the families who work there, that it is intrinsic to business that it will undermine the family (for example through demands of time) and so many other aspects of an ordered culture. I do not accept this.

Culture reflects the cult that is at the core of it. However modest the fulfilment of this ideal, this is the means by which the culture of community or organization can be transformed to a Catholic culture that will be in harmony with all other institutions and social groups and work for the common good. It is no surprise, therefore, that any organization, such as many businesses which typically give no thought to liturgical piety at all, reflect a secular culture. So much so, that it doesn’t even occur to many people that the workplace can be or can even aspire to be a community. Consequently it is taken for granted that while it might contribute to the financial support of the families who work there, that it is intrinsic to business that it will undermine the family (for example through demands of time) and so many other aspects of an ordered culture. I do not accept this.

This suggests though that any attempt to change things in a community or organization that does not consider its culture and what culture really is will be dealing with symptoms not causes; and the problems even if apparently solved will eventually reappear elsewhere or in a different form. It is like the Tom and Jerry cartoons when Tom has hit on the head with a giant mallet and has a huge bump on his head. In response he puts his hand on the top of it and pushes it down until the scalp is once again smooth. The only problem is that as the first bump diminishes, a second appears on the side of his head and grows. The end result is that the bump has simply moved. Most organizational change I have seen in the workplace has struck me as bump moving, rather than bump healing.

In the end, I suggest, that answer is always the same: to change a culture you must change the cult.