As an artist, I am aware of the need for inspiration and creativity in my work. Traditionally, artistic training was one that was designed not only to teach artists the skills of their craft, but to develop in them the disposition to be open to God’s grace.

In fact all students, not just artists, can benefit from being open to God’s grace in their work. By examination of the structures of the colleges of Oxford University one can see that traditionally Catholic educational institutions were structured so that they facilitated the flow of grace, by ordering all their activities liturgically. That is, they lived by the rhythms and patterns of the liturgy, so that their activities both ushered in grace and were open to guidance from it, for the good of all. Even the design of the buildings was done so as to assist in the liturgical life.

By extension this leads us to consider the possibility of ordering any social institution liturgically, so that it can flourish as God intends. This article considers particularly business. Even a business can be ordered liturgically, joining all of creation in praising the Father and becoming a portal of grace. Such a business would support the human person fully – materially and spiritually – and be a beacon of truth and beauty that assists man in his mission of worship of God, charity to mankind and the perfecting of creation.

Part of my study as an artist was in Florence, in Italy, where I was trained in the academic method of drawing and painting.

The academic method is named after the art academies of the seventeenth century. The most famous early Academy was opened by the Carracci brothers, Annibali, Agostino, and Ludivico, in Bologna in 1600. Their method became the standard for art education and nearly every great Western artist for the next 300 years received, in essence, an academic training. Under the influence of the Impressionists the method fell out of favour so that by 1900 nearly every school teaching the academic method had closed down (the US academies in, for example, Boston, lasted a bit longer).

Within the last 30 years there has been a small but growing re-establishment of the academic method in both Europe and America. The founder of my school was trained by an octogenarian in the 1970s who had studied in Boston about the time of the First World War. By the time of my attendance there in 2005, there were four schools in existence in Florence, each teaching a similar form of “classical naturalism.”

Along with all of the students who attended, I am immensely grateful for the excellent education in technique and the stylistic elements of seventeenth-century Baroque naturalism. Despite this, pretty much everyone at this atelier agreed on one thing: although there were some good contemporary artists, no one in the modern era was producing work of anything like the quality of the old masters (Velazquez was the standard we aspired to). This realization cast a cloud of pessimism over the ateliers of Florence. Something seemed to be limiting the standard of the students. If classical naturalism was to become a mainstream art form again, the students would have to be getting steadily better and surpassing the work of their teachers, but it didn’t seem to be happening.

The pessimism was exacerbated when one looked at the work of the students once they had left these schools. Some were happy doing precisely what they had been taught. They could make a good living as portrait painters, or paint traditional still lives of high enough quality to sell in the alternative “realist” art market of the US. There is a valid place for this sort of art today, in my opinion, but it would never be the basis of the required “new epiphany of beauty” called for by John Paul II. Others who left felt the need to use what they had learnt and develop it. The mark of any truly living tradition is an evolution of style that nevertheless remains faithful to the timeless principles that define it. The problem was that no one seemed to know how to change anything without eroding what we had learned.

I saw a number of people struggling with this. They might introduce some exaggerated and expressive brushwork, or some heightened colour. Guided only by their own gut feeling of what was right they travelled on their own little personal journey through the artistic styles of the later centuries – Romanticism, Neo-classicism, Impressionism, Fauvism, and Expressionism. Some settled for a style somewhere along the way, perhaps with an expressionist or a fauvist influence dominating. Others, sometimes the most talented, knew this was a path that was leading them to the place that they had sought to escape, and after a struggle gave up painting altogether in disillusionment. It seemed that whatever was being given to us contained the same fatal flaw, whatever that might be, that caused the tradition gradually to decline and then finally to collapse when challenged by Monet et al. 100 years before.

How could students break out of this downward spiral?

It seemed to me that there were two things missing in our education. The first was a lack of full acknowledgement and hence limited understanding of the fact that the style we were learning was the product of a Catholic worldview. With a few notable exceptions, the old masters, even if not conventionally Christian, accepted the worldview that the stylistic elements of Baroque art were developed to communicate.

The second reason is one that was apparently ignored completely, and yet it is something that is important in all education: the necessity of grace, without which wisdom and virtue cannot be developed. If Velazquez was the standard we were aiming for, then something must have allowed him to be greater than his own teacher. Perhaps the answer lay not just in Velazquez himself, but in the education he received.

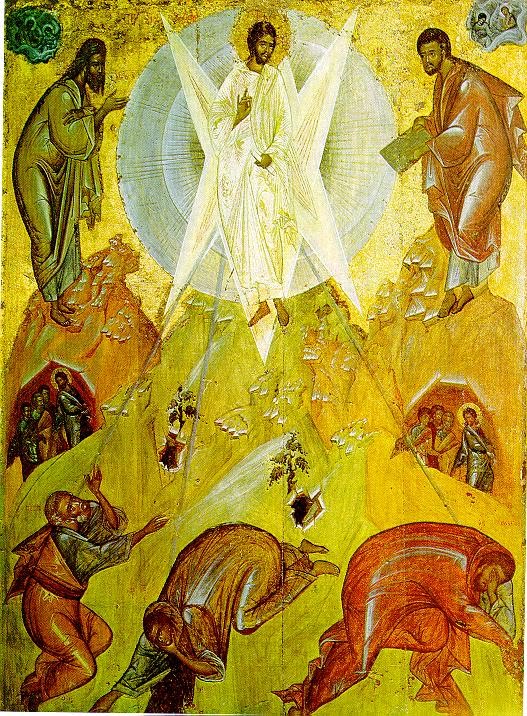

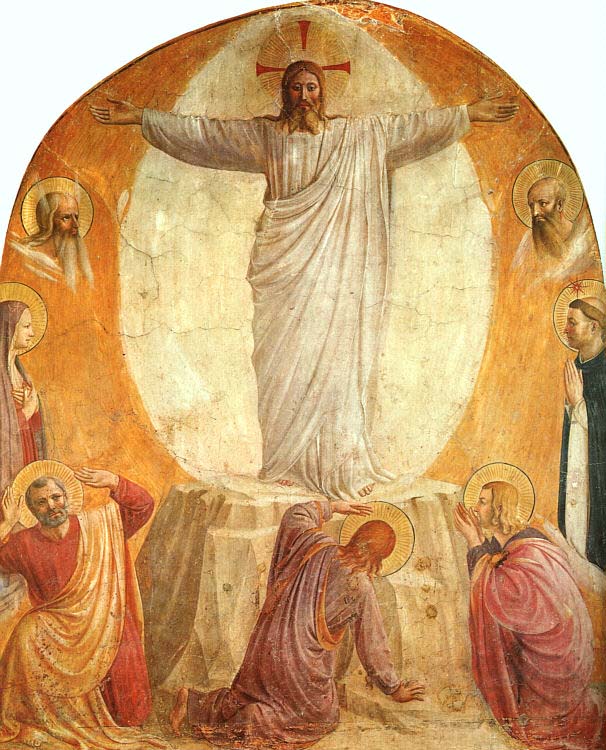

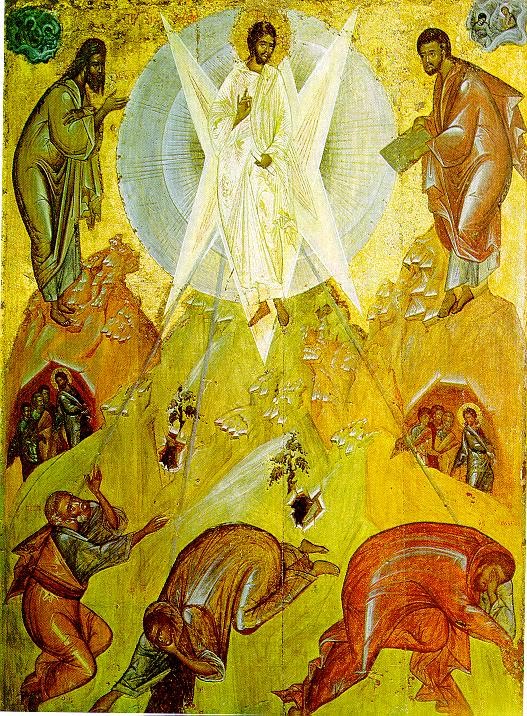

Velazquez’s teacher was his father-in-law, a Spaniard called Francisco Pacheco. He published an instruction manual for painters called El art de la pintura in 1649. This articulated what an accepted authority on the Baroque, John Rupert Martin, called “the clearest definition of the transcendental significance of Baroque naturalism.” Pacheco clearly sees the role of the artist as being to imitate nature in order to bring glory to God. In doing so, he asserts, he will be practising a virtue. Therefore the act of painting will serve to lead both artist and those who see the painting to “contemplation of eternal glory, and as it keeps men from vice, so it leads them to the true devotion of God our Lord.” In doing this the artist will achieve his principal goal, which is “to achieve a state of grace through the study and practice of his profession.”

Velasquez’s training was as much an education in humility and apprehension of beauty as an education in skill. It was designed to open him up to any inspiration that God might choose to give him. He was taught to study nature and the work of recognised masters with self-discipline and under the careful eye of his teacher, who corrected him along the way. But if the process of education were limited to passing the knowledge of the teacher on to the student, then because no teacher can hope to pass on everything he knows to his pupil, it would necessarily involve a diminution of knowledge. Clearly in the case of Velasquez something had enabled the pupil to surpass his teacher. The obvious answer is sheer talent – the genius that enables one person to excel another. We live in an individualistic age, and the post-Renaissance obsession with artistic genius makes it hard to conceive of any other factor. But talent is a gift from God, and not necessarily the most important in producing truly great work. Artistic inspiration itself is a gift, as any artist will tell you. The beauty of nature is a gift, when we recognize that all things come from God. The deeper answer, therefore, is grace. Velasquez surpassed Pacheco partly because of how he responded to the grace of God.

Of course, not every great artist is a Christian, or even a virtuous person. God inspires whomsoever he pleases. But when it comes to opening ourselves to the grace of God, participation in the sacramental life of the Church is likely to help dramatically. “All true human art is assimilation to the artist, to Christ, to the mind of the Creator…. When a man conforms to the measure of the universe, his freedom is not diminished but expanded to a new horizon.” ((Joseph Ratzinger, The Spirit of the Liturgy (Ignatius Press, 2000), 153.)) I do not know if Velasquez was as fervent a believer as his teacher, but as part of the court of seventeenth-century Spain, he will at least outwardly have been a Catholic conforming to the liturgy of the Church. Through that liturgy we can become attuned to the deepest of all sources of inspiration.

How the consideration of grace can affect the organisation and physical structure of an educational institution

The example of Velasquez and his education in beauty could provide an important lesson to anyone seeking to develop a method of education – and not just the education of artists. An education in the perception and making of beauty is inevitably an education in opening up to inspiration, an education of the intuitive faculty that gives us insight into reality. It is hard to see that there is any academic discipline (or for that matter any human activity) that cannot be improved by a development of the intuitive faculty. The scientist tests his hypothesis in a step-by-step application of reason by the experimental method, but the hypothesis itself is more often than not the result of intuition.

Once one accepts the importance of grace it can affect the design of the institution right from the curriculum through to the layout of the buildings and the living arrangements, as well as, most obviously, the sacramental life. As the liturgy is the source and summit of human activity and all aspects of human life can be ordered to it.

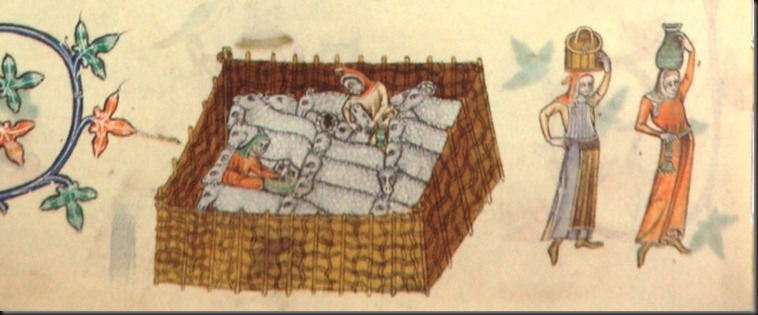

The college system at Oxford University can be used to illustrate this. From the thirteenth century, residential educational institutions were founded by the new orders of friars, the Dominicans, the Franciscans and the Carmelites as well as the older monastic orders such as Benedictines and Cistercians and the bishops. The community was infused with the rhythm of the heavenly liturgy through participation in the Mass and the Divine Office. The full Office was sung each day, if not by the whole community each time, then by some of its members on behalf of everybody within it.

The liturgy is a source of grace for those who pray it, and by participation in the liturgy, the person becomes a portal of grace that benefits those around him too. In these colleges the whole community would have benefited from living in accordance with a divine rhythm, making the whole greater than the sum of the parts. The sense of a community was reinforced by the practice of communal eating. Eating in community is a quasi-liturgical event echoing the Last Supper, which binds together a family as much as a college. It is interesting to note when looking at the colleges of Oxford how much energy was devoted to making the whole college a beautiful place and how nearly as much energy went into making the Dining Hall beautiful as was used for the Chapel. The library was also created as a room of beauty in order to create a room of inspired learning. When designing the buildings, it was not left arbitrarily to each architect to come up with something original. The proportions of the building followed traditional ideas of sacred geometry that created a physical manifestation of liturgical principles. ((The Way of Beauty; Let the Form Conform; The Cosmic Liturgy and the Mind of God; Number; Harmony and Proportion))

As the University expanded it did so mainly by the establishment of new colleges, rather than by the growth of existing ones. This meant that it remained a series of communities so limited in size that each was able to pray and eat together regularly. Even after the Reformation in England, the liturgical rhythm continued in Oxford in form (if not fully in substance) through adherence to daily Anglican offices and services. Even today Mattins and Choral Evensong are sung daily in some colleges during term time (even though many students never attend); and students are required to attend formal meals in hall.

During my four years as a student at Oxford, which was long before my conversion to Catholicism, I did not even once go into the college chapel. Nevertheless I can now see how profoundly I benefited from the fact that others sang the Liturgy of the Hours on my behalf. In this sense I was a freeloader, enjoying the benefits derived by the work of others. It was after I left Oxford that I suffered. Without the spiritual support of the community (although I wasn’t aware initially that this was the primary reason) I was lonely. Although I had people around me, at work and where I lived, I had not developed the good habits that enable me to be the leaven that could create fellowship around me. It was not until I became a Catholic that I understood that fellowship comes first from the Holy Spirit and that I can receive that fellowship through participation in the sacramental life and especially the liturgical rhythm of the day, even if no one else around me is doing so. It ushers in the Spirit that binds people together. It turns a group of people into a community (liturgy is worship of the Father, through the Son, in the Spirit and is what the other sacramentals and sacraments are supporting).

Things have changed since the England of the Middle Ages. There could hardly be greater contrast between the founding of Christ Church College in Oxford by Cardinal Wolsey in 1524, with all the wealth of the sixteenth-century Church at his disposal, and the establishment of the Catholic colleges in the last 30 years or so. For all the differences, though, the success of each institution may be attributed to some basic structural considerations. Essentially, an educational community that succeeds in delivering a good education will be one that facilitates – or at least does its best not to block – the flow of divine grace. We tend to think of education as a process that connects teachers and students. But unless God is somehow present as well, as the third factor, the community will ultimately fail to deliver an education in the fullest sense of the word. This in no way replaces the usual consideration of what might constitute the optimal combination of lectures, seminars, tutorials, exams, and coursework. These are vital matters too, off course. Rather, they enhance them further, for without changing them materially they make God present within them.

In my personal experience, I have seen these ideas implemented to great effect at the Maryvale Institute, in Birmingham, England and now at Thomas More College of Liberal Arts in Merrimack, New Hampshire. At Thomas More College, through the Way of Beauty programme we explain how the daily Mass, the Liturgy of the Hours, and college devotions ordered to the liturgy, such as the rosary, weekly exposition and the nine, monthly First Fridays of the devotion to the Sacred Heart are there for sound educational as well as religious reasons.

Institutions other than college – the beautiful business

If we accept the idea that we can order educational institutions in such a way that they encourage the flow of grace, then it should be possible to extend the principles to other institutions too. If recent events are anything to go by, commerce is an area which could benefit from grace. So can a business be ordered liturgically? Is it worth doing so even if we can? I believe that the answer to both questions is yes. The following are my first personal thoughts on the subject.

The Fathers of Vatican II said that ‘for well disposed members of the faithful, the liturgy of the sacraments and sacramentals sanctifies almost every event in their lives; they give access to the stream of divine grace which flows from the paschal mystery of the passion, death, the resurrection of Christ, the font from which all sacraments and sacramentals draw their power. There is hardly any proper use of material things which cannot thus be directed toward the sanctification of men and the praise of God’. ((Sacrosanctum Concilium 61)) This says to me that anything that is intrinsically good can be ordered liturgically to give praise to God. We should therefore be aiming to make all our activities and anything we produce consistent with this liturgical principle of worship of God the Father. We can look at those aspects of our daily lives that might seem, at first sight, to be most mundane and removed from church worship and order them liturgically, and this can include gainful employment. If we do this then our work will, through grace, become exactly what God intends it to be, a profitable flourishing company.

Some will instinctively react against a proposal that seems to say, ‘God is good for business.’ This is understandable. It conjures up images of the sparkly-toothed business guru selling us the idea that the introduction of spiritual values into the daily transaction of business will increase profits. Go to any bookstore and you will find shelves of books claiming to show how (inverting the natural hierarchy) we can harness the power of God to generate riches. I cannot attest to whether or not this pray-and-grow-rich message generates money for anyone other than the authors of the books who claim it. However, at some level, God must be good for business if business is good at all. Any institution ordered properly, will be open to God’s grace and will, with the cooperation of individuals within it, become what God intends it to be and so will benefit it. Business is no exception, once it is ordered liturgically, it can be directed towards the sanctification of men, just as the Fathers of Vatican II describe. This in itself is an end worth striving for. The Canticle of Daniel, sung in Lauds of Sunday Week I in the Liturgy of the Hours, and on all feasts, lists all aspects of creation and beautifully defines them as liturgically ordered by describing them as ‘giving praise to the Lord’. Our aim should be to order business in the same way, so that we could add, ‘Oh all you businesses of the Lord, give praise to the Lord. To Him be highest glory and praise forever”!

The Catechism tells us directly that just as the natural world is ordered to worship of God the Father, so should all man’s activities be similarly ordered: “Creation was fashioned with a view to the Sabbath and therefore for the worship and adoration of God. Worship is inscribed in the order of creation. As the rule of St Benedict says, nothing should take precedence over the ‘work of God’, that is solemn worship. This indicates the right order of human concerns.” ((CCC, 347))

Does this mean that ordering the business so that it will be open to God’s grace will generate more profit also? The answer is yes, possibly, and certainly over the long term because the generation of profit is part of what a business ought to do. (The exceptions are when the core business is contrary to moral law and the common good – those aspects other than profit to which a business ought to be ordered.) But the point here is that it should create other things as well. The Catechism of the Catholic Church tells us that the ‘Economic life is not meant solely to multiply goods produced and increased profit or power; it is ordered first of all to the service of persons, of the whole man, and of the entire human community...Human work proceeds directly from persons created in the image of God and called to prolong the work of creation by subduing the earth, both with and for one another...Everyone should be able to draw from work the means of providing for his life and that of his family, and of serving the human community. Profits are necessary, however, they make possible investments that the future of a business and they guarantee employment.’ ((CCC, 2426, 2427, 2428, 2432.))

If the economic life ought to be ‘ordered first of all to the service of persons, of the whole man, and of the entire human community’, or as Pope Benedict XVI refers to it in his encyclical Caritas in Veritate, ‘the common good’ this makes things complicated for the faithful businessman. How can he possibly deal with the practicalities of generating profit, without which the business cannot exist at all, and consider its impact in the world through the network of seemingly infinite direct and indirect relationships with which it is in contact?

Experience tells us that many employers are aware of such obligations and genuinely try to fulfil them. They make attempts to modify the nature of their business in order to be more family – or environment – friendly. However, very often such attempts create a competition for resources because the profit making activity is not the same as that which supports the family or the environment. So as the focus on reducing harm to family or environment goes up, profits go down. The test of the truth of this is that when times get tough economically, employers cut (albeit usually with regret) the benefits to their employees or abandon any ‘green’ policies they are not legally obliged to keep.

If this is what happens, it is a consequence of the fact that the attempts consciously to conform to the common good are in conflict with its core profit making activity. Therefore the more eco or family friendly the company tries to be, the less business it does. Government attempts to force companies to do such a thing tend to create the same tension. Reducing productivity either by regulation (which effectively forces the company to bear the cost of social or environmental measures) or by taxation (to enable the government to pay for such measures).

An alternative, I suggest, is to order it liturgically first and then to strive for generation of maximum profit. Profit is an end to which a good business is ordered. It is the most necessary condition for its continued existence and the easiest guiding principle to apply. This therefore should be the primary motivation. The application of morality tempers this aim however: we should not, for example, take actions that are dishonest. If morality is completely contrary to the profit motive, then we are in an intrinsically bad business (such as drug dealing) and we should close it down.

Similarly, considerations of the common good, as an aspect of morality, should also be seen as potential modifiers to the primary motive of profit, rather than a primary guiding principle. Being ‘ordered to the common good’ does not mean that all mankind should benefit materially directly from what a business does. It simply means that it acts in accord with the small part laid out for it in God’s overall plan. It is God’s overall plan which is directed to the common good and affects all. It is usually very difficult to predict the impact of our actions beyond those directly affected and so it is better for the most part, not to try. Attempts to do so, aside from reducing profits, will just as likely lead to unforeseen and detrimental secondary effects. Rather, we should aim to order it liturgically, and trust that grace will direct us in following our intuitive judgement in following the profit motive, to do what is best. This is not to say that there should be no consideration of the common good at all. Just as with consideration of morality, it is possible that sometimes it will temper behaviour that would otherwise be driven by the pure profit motive. If we can see that the profit is generated to the benefit of a narrow group of people, but it is obvious that the secondary or general consequences of this are contrary to the common good (for example causing damaging levels of uncontainable pollution) then we should modify our actions. It is this intuitive aspect that will lead us to make the more creative and productive ideas, quite naturally, in the environment that encourages it.

The good business, one that is ordered to the supernatural, generates profit to pay its employees and gives return to its investors; it also supports spiritually those it impacts upon. It is a social institution in itself and one that helps to bind the families together, rather than undermine them by, for example, making excessive demands of time. It is one that works in harmony with the natural world. Its activities and products are directed towards the sanctification of men and, through their beauty, give praise to God. To the degree that a business is ordered liturgically, because it is in harmony with the divine order, it is impossible for the generation of these goods to be anything but in harmony with each other. Therefore, all these other benefits can be accrued through the core, profit-making activities of the business. Pope Benedict, again in Caritas in Veritate, said that the rule of a business ordered to the common good is one of ‘superabundance’. He is not therefore describing a principle that reduces profit, but one that, potentially, adds to it. The good business will last as long as God intends and grow to the degree the He intends. If it is meant to exist at all, given the full range of goods that derive from a good business, there is no reason to believe that sustainable profit will not be one of the results.

There is an assumption by some that the motive for a business transaction is a selfish one. To my mind, while we might describe the motivation as one of self-interest, in the sense that each party is seeking to benefit from it, this self-interest is not necessarily selfish, in the sinful sense. A profit motive, for example, can be either selfishly driven or unselfishly driven – it depends on what you want to do with the profits. Profit is neutral, just as with all money or wealth. Certainly, it can corrupt or give those already corrupted greater power to fulfil sinful intentions, but not necessarily so. The converse can be true. It has the potential also to empower people to do greater good. An action is sinful, and therefore bad, when measured against the objective standard of God’s will. If God wishes us to earn money to support ourselves or our families, then it might be construed narrowly as selfish, but it is certainly not sinful to strive to do so by directing our actions towards greater pay or profit, or purchasing a product at a cheaper price. The greater good, at the individual level and beyond, therefore, is always achieved to the degree that individual motives (most likely mixed in practice) are ordered to what is good and individuals are free to choose to make such decisions; and to the degree that they work within institutions that are structured in harmony with the divine order, so as to encourage and harness the good individual decisions to the common good. The natural extension of this argument is that the business environment, ie the market, beyond the institution should also be one that is ordered to common good so that which will encourage such individual choices, and direct it to what is good for society as a whole. The perfect market environment is a debate for the economists, but it seems to me that it is the free market, prudently regulated according to the principles of justice.

The Catechism directed us to the example of the rule of St. Benedict in describing an ordering principle for work and we look to the Benedictine monasteries for inspiration and confirmation of this. Through right ordering in accordance with liturgical principles, the benefits generated by monasteries have been both material and spiritual. Furthermore, the material wealth generated has at times been so great that it was viewed with envy by the state and secular rulers, such as Henry VIII of England. The Benedictine Rule could be viewed as the most successful and long-standing business franchise in history! ((It should be pointed out, in fairness, that the picture is not one of complete purity. The various reforms to the order over the centuries point to the fact that some Benedictines were as unable to resist the corrupting power of money as the rest of us.))

The Beautiful Business

Any work that is in harmony with the divine order is perceived by us as beautiful. A business so ordered will work beautifully and the product of its work will be beautiful. It cannot be otherwise because beauty, truth and goodness cannot be in opposition. Beauty attracts people to itself and then beyond to God. Through grace, the work of man can potentially surpass even natural beauty. The beauty of the Oxford colleges continues to be a factor in the attraction of students from around the globe, increasing competition for places and so raising standards. Similarly, when the goods and services offered by the company are beautiful or presented beautifully, their value is increased because they are deemed more desirable. The value of goods and services, and hence productivity have increased.

All these benefits will increase in the liturgically ordered business as people follow their intuition, guided by reason, in following the profit motive, modified whenever this contradicts morality or affects adversely the common good. We are talking as much about how people act as what they do. Usually consideration of pure profit motive generates answers to what is done. How those ends are achieved will be the product of the attitudes of those who take them to their fellow man. It will demonstrate whether he values those people or views them simply as a means to an end. Ultimately it is the how which is a much, perhaps more so, the creative principle in all that we do and which generates wealth.

Why harmonious relationships create material and spiritual benefits

A harmonious relationship is one that is ordered to the divine order. Such a relationship creates something out of nothing, by allowing the supernatural to work through it. This is the source of that superabundance. All decisions made within the working day can benefit from this. Whether they are managerial decisions that affect overall strategy or simple choices made at an almost instinctive level that affect our manner in dealing with others as we go about our daily duties, all can be open to the grace that flows through harmonious relationships. Projects, products, new services and intellectual property are all created and implemented by this process of harmonious relationship which acts as the driver of corporate growth, revenues and profitability, plus, vitally, meaningful work, jobs and well-being for employees and their families. Very often this is manifested in apparently quite straightforward ways, although they are masking a supernatural process. If the relationship with the customer is built on the right principles, they will be your unpaid travelling salesman, drawing others to you through enthusiastic recommendation because they enjoy the service you provide. Even those who are unfortunate to be laid off can be our advocates in the future if they are treated in a way that respects their human dignity. Going back to our Benedictines again, it is worth noting that their monastic vows included one of stability, which kept activity outside the perimeter of the monastery to a minimum. Despite this, even during the so-called dark ages of the centuries after the collapse of the Western Roman Empire, monastic trade and communication extended from Ireland to Byzantium.

What is a harmonious productive relationship?

Consider two musical notes. These can exist in isolation but when they played simultaneously something new is created, a chord. If each note is in a harmonious relationship with the other, we will recognize it as something beautiful. What is interesting about the chord is that is created out of nothing. Without destroying the integrity of each individual note, a new third entity has been created.

When we talk of harmonious human relationships, we are referring to a cooperative, harmonious alignment of wills. In fact the most harmonious relationships are those that we would call loving relationships. When we have loving relationships we talk of two hearts beating as one. In considering what this means for us, we can look at the type for all loving relationships, that which exists between the persons of the Trinity. In fact all harmonious, loving relationships are an unfolding of the perfectly harmonious relationship of the Trinity. The love between two of the persons of the Trinity is crystallized as a third person. St Augustine in De Trinitate described the relationships between the persons of the Trinity as follows:

“Now love is of someone who loves and something is loved with love. So then there are three: the lover, the beloved, and the love (Bk 8 Ch 10). If then, any one of these three is to be specially called love, what more fitting than that this should be the Holy Spirit? In the sense, that is, that in that simple and highest nature, substance is not one thing and love another thing, but that substance itself is love and that love itself is substance whether in the Father or the Son or the Holy Spirit, yet that the Holy Spirit is especially to be called love” (Bk 15 Ch 17)…

This is a description of perfect love; mutual self-gift, in which each person gives him or herself to the other utterly and totally. St Augustine goes on to say (Bk 15, Ch19:36) that ‘there is no subordination of the Gift and no domination of the Givers, but the concord between the Gift and the Givers’.Just as in the chord: two notes combine to form something totally new, the chord, but neither is compromised or diminished by their interaction. The ‘chord’ of the harmony of wills in mutual self-gift is Love. It makes God, who is love, present.

It is this love that is the productive component in the relationship. It generates something out of nothing in a supernatural process. All of creation is made by this love. We know that the cosmos is made by God because its beauty directs our souls to the divine order. The word cosmos is derived from the Greek word that means simultaneously ‘order’ and ‘beauty’ (hence the word ‘cosmetic’).

No other relationships are as profound as that of the Trinity, but any relationship that is founded on the principle of love, that is one of mutual self-gift, entered into freely, will, by degrees resemble this Trinitarian model and will be productive in a manner that is in due proportion to the nature of the relationship. This is true for every human relationship from marriage right through to casually passing the time of day with the bus driver.

It is important to note that we are living in a fallen world, and so seeking to institute a covenantal model of operation does not preclude contracts. Contracts regulate the relationships in accordance with the principle of justice. Contracts are very often necessary, but they are never enough. Contracts alone cannot generate the trust and goodwill that oil the wheels of commerce. This is generated by individuals going beyond the demands of justice – and acting in accordance with the principle of love. Pope Benedict XVI calls this covenantal aspect in the context of business ‘gratuitousness’. This is just as it is in marriage. Marriage is defined within the legal system of society as much as the religious. However, a marriage that operates as though it were only a legal contract lacks love and will not last. The contract defines the minimum level of participation. For a marriage to operate at a covenantal level it requires each party to give to degree that goes way beyond legal minimums. It is the free expression of love – giving without demanding return – that makes God present, because God is love. It is what makes it an abundantly productive relationship.

Similarly, the free market is regulated by law in accordance with the principles of justice, and within this contractual agreements describe the participation of individuals and companies within it, again, if done properly, according to justice. But it is the covenantal behaviour that permeates this legalistic structure that generates wealth. Trust and goodwill are necessary components of commerce.

The corollary to this is that the lack of a covenantal approach to relationships in business can cause the downfall of a company when by all other measures it should succeed. Often, there is no economic rationale and the only explanation for such a downward-spiral is the human failings of egotism, vanity, greed.

How do we do order a company liturgically?

One approach is to teach CEOs and those who are in a position to shape a business, the ideas behind the traditional quadrivium (as the Way of Beauty and Thomas More College of Liberal Arts does) so that they can structure a business in accordance with it. Just as with a college, the environment can be created, through the ordering of time and space that encourages a liturgical mode of behaviour in its employees. An institution cannot love, but the individuals within it can. If even one person cooperates on behalf of the community, then it ushers in grace from which all within it can benefit.

In addition, those employees who are open to it can be taught the same principles so that through their free cooperation they and the company will benefit. There can be no compulsion or sense of obligation here for these undermine the principle of charity upon which it relies for its power.

Even if the company as a whole is not structured liturgically at all, it is possible for a single employee to introduce grace by praying for the company in accordance with the liturgical principles and by cooperating with grace, to treat better his fellows in accordance with the principles of caritas. This will introduce the transforming principle that benefits all and draws others to it so that by degrees the culture of the company transforms.

Enhanced Creativity in Business

When we apprehend beauty, we do so intuitively. Therefore, an education that improves our ability to apprehend beauty, as Thomas More College’s Way of Beauty does, develops also our intuition. All creativity is at source an intuitive process so this education develops their creativity. Furthermore, that creativity will stimulate in those employees who undergo such a course not just more ideas, but better ideas. Better because they are more in harmony with the divine order. The recognition of beauty moves us to love what we see. It is a transforming principle so such an education would tend to develop also, therefore, our capacity to love and leave us more inclined to serve God and our fellow man. The end result for such an individual is joy.

Beauty like morality, then is a principle of life that guides our freely chosen activities, so that we choose well. Morality tends to work on a negative basis – it cuts out options on the basis that they are immoral. Beauty on the other hand, is a principle that opens up new possibilities and so in contrast to morality works on a positive basis. It is a principle of creativity, which is vital in business. For those whose intuition is tune with the natural order and ultimately the divine order, seeking do what is most beautiful will guide our personal preferences to those choices that are going to be most productive and in harmony with the common good.

Another approach to tapping into the principle of superabundance is to develop further those covenantal relationships that already exist. No group of people is without any covenantal relationships. Within any company there is a natural network of them. These in fact represent, supernatural means, its most important wealth-creating assets. They develop out of the informal contact of employees, clients, customers and the friendly relations and friendships that ensue. They sit alongside and permeate through the formal managerial communication lines. There are many business people who will recognise this and see these relationships as assets. Fewer will recognise this as the supernatural basis for the creation of wealth. ((I am aware of one who does this consciously: John Carlson of System Change Inc (www.systemchange.com) has developed to great effect a method of transforming companies so that their generative covenantal relationships are identified and nurtured and their business strategies modified to encourage and benefit from them. He has been doing this with great success for many years. His work has shown that the effect of applying of these principles is to generate sustainable profit and to make employees feel valued and motivated to work more productively. It becomes, in short, happier more productive place.))

Conclusion

A liturgical ordering of business not only defines how a business can operate in harmony with the divine order; it is also a transforming principle that enables the business to move towards this ideal. If there is a conflict between the generation of wealth and these other goods then in the liturgically ordered business, grace will tend either to transform it into one in which the conflict is diminished and eventually eliminated; or, if the nature money-making activities of the company are intrinsically bad and unreformable it will tend to put it out of business. Racketeering, drug dealing and pimping would not flourish through the introduction of these principles!

The effect of this will be to maximise sustainable profit while benefitting the whole person and the common good. It is the best way to improve workers’ conditions, to improve their involvement with their families and to enhance the environment. In other words in such a company, the more core business that is done, the better it is for those involved, by any measure of good. By following the motive of maximising profits, modified only when it contradicts morality (and as part of the common good), it would tend to perfect and improve the natural environment (or, quoting the Catechism again, ‘prolong the work of creation by subduing the earth, both with and for one another)’. It will affect those with whom it comes in contact so that it works for their sanctification. And through its beauty it will praise God and bring joy to man.