A beautiful Christian culture draws people to Christ. It opens up the minds of those who are not believers to be receptive to the Word, and it reinforces the truth of the Word to those who are already believers.

Scala Foundation - Playing a Crucial Role in the Evangelization of the Culture and Breaking the Mould of Education

Attend the spring conference, Art, the Sacred, and the Common Good, at Princeton, NJ, April 30th, 2022. Free to register and attend.

I want to highlight the work of the SCALA Foundation. The Scala Foundation’s mission is to renew American culture by restoring beauty and wisdom to the liberal arts. Scala’s seminars, reading groups, conferences, summer programs and online resources help educators and culture creators engage the millennia-old tradition of liberal arts education and its power to form virtuous, purpose-driven citizens, form young leaders who are pivotal agents of cultural renewal, and build communities of like-minded cultural entrepreneurs and magnify their impact.

Some may remember that I recently spoke on the Scala webinar, listen here. or here. She has also invited me to be on a panel for the SCALA 2022 conference - Art, the Sacred, and the Common Good - in Princeton NJ this April, which is free to attend.

The focus of SCALA is in creating creative communities at a local level that are able to contribute to Catholic education locally and to the culture through the creation of art, music, literature etc (eg she organizes writers' workshops).

It occurs to me that SCALA is offering programs that complement formal online education, such as that offered by www.Pontifex.University, where I work, and when the two approaches to student formation are combined offer a genuine opportunity. The zoom revolution that has happened as a result of Covid has opened up people’s minds to the idea of online education.

The advantages of this are that high-quality and standardized educational material can be delivered at a fraction of the cost of the traditional on-campus experience. However, I am conscious that providing community of learning - so important in education - is the weakness of online education and while things are improving, it is clear that Facebook pages and chatrooms don't fill the gap. This is where SCALA comes in. They are guiding educators and artistic creatives who can contribute to a culture of beauty to form communities locally.

I am encouraging Pontifex students to attend and participate in the conferences and events and meet each other, (and me if they are interested!) so that they might start to form communities with each other locally under Scala's guidance. It is these local communities, it occurs to me, which might be portals for grace and love that can transform the culture.

Discerning Vocation: How I Came to be Doing What I Want to Do

Farms, Country Walks, Private Property and the Common Good

I am a keen walker and when I moved to the United States ago to take up my position as Artist-in-Residence at Thomas More College, I immediately started to investigate the local country walks. I lived Nashua, a town in New Hampshire, very close to its southern border with Massachussetts. Both are beautiful states and there are state and national parks with developed paths within striking distance of here. These are very different from the British country walks that I am used to however. The countryside in Britain is almost all farmland of some description. So whereas in the US, as a general principle, the state and national parks aim to present man with a ‘wilderness’, that is countryside unaffected by man, the British national parks preserve a traditionally farmed landscape.

I am a keen walker and when I moved to the United States ago to take up my position as Artist-in-Residence at Thomas More College, I immediately started to investigate the local country walks. I lived Nashua, a town in New Hampshire, very close to its southern border with Massachussetts. Both are beautiful states and there are state and national parks with developed paths within striking distance of here. These are very different from the British country walks that I am used to however. The countryside in Britain is almost all farmland of some description. So whereas in the US, as a general principle, the state and national parks aim to present man with a ‘wilderness’, that is countryside unaffected by man, the British national parks preserve a traditionally farmed landscape. Creating a network of walks across privately owned farms is possible in Britain because in this respect the attitude to private ownership of land is different in England to that in the US. In England there are public rights of way across private land which the landowner is obliged by law to maintain. In return, the public is expected to respect the land and the farmer’s crops and animals and stick to the path. There are many thousands of miles of public footpath across private land. This is a system which would be impossible to police effectively, yet it works. On the whole the farmers happily keep the paths open and maintain them for the benefit of walkers, and the whole the public respects the farmers’ land, crops and animals. So although backed up by law, it is founded mainly on mutual trust and respect. It is working example of the good that arises when individuals go beyond a strict interpretation of the law and create a covenantal approach for the benefit of the common good.

Creating a network of walks across privately owned farms is possible in Britain because in this respect the attitude to private ownership of land is different in England to that in the US. In England there are public rights of way across private land which the landowner is obliged by law to maintain. In return, the public is expected to respect the land and the farmer’s crops and animals and stick to the path. There are many thousands of miles of public footpath across private land. This is a system which would be impossible to police effectively, yet it works. On the whole the farmers happily keep the paths open and maintain them for the benefit of walkers, and the whole the public respects the farmers’ land, crops and animals. So although backed up by law, it is founded mainly on mutual trust and respect. It is working example of the good that arises when individuals go beyond a strict interpretation of the law and create a covenantal approach for the benefit of the common good.

As a result, everyone in Britain has the chance to see firsthand how man can cultivate and work the land for benefit of all of us. This goes further than simple recreation. For those who wish to accept it, there is profound lesson to be learnt. Creating the possibility for all people to come into direct contact with land that has been worked by man beautifully will teach us that man is capable of working productively with the land in harmony with it. This counters the false idea that man’s activity is necessarily destructive and ‘unnatural’. This latter point is one of the fundamental premises of neo-paganism. It is an anti-human principle, which leads ultimately to the culture of death.

As a result, everyone in Britain has the chance to see firsthand how man can cultivate and work the land for benefit of all of us. This goes further than simple recreation. For those who wish to accept it, there is profound lesson to be learnt. Creating the possibility for all people to come into direct contact with land that has been worked by man beautifully will teach us that man is capable of working productively with the land in harmony with it. This counters the false idea that man’s activity is necessarily destructive and ‘unnatural’. This latter point is one of the fundamental premises of neo-paganism. It is an anti-human principle, which leads ultimately to the culture of death.

Some Americans might react sharply and suspect that this an example of the state overreaching itself. However, the idea of the right of the public to cross private land goes back to medieval times. It could not be enforced by the state anyway, because as explained earlier, it relies not so much on the law, but on mutual respect for its effectiveness. The way it worked was this. The landowner, perhaps the lord of the manor, agreed to allow men to farm a strip of his land to grow food in exchange for a tithe, a taxation of a tenth of the produce. The tithes were collected in huge barns – ‘tithebarns’- the photographs, above and below show one example that still exists in Oxfordshire in England. However, there was a problem. Our serf might have the land to grow his food, but if it is situated in the middle of a large estate owned by someone else, how is he going to get to it without trespassing? To overcome this, a system of pathways developed that ensured that people could get to their land without fear of prosecution. They were allowed ‘right of way’. They could cross someone else’s land provided they followed the path and respected the property. This is part of an old tradition of noblesse oblige. This is a French phrase which means literally, ‘nobility obliges’. It communicates the idea that with privilege comes the responsibility to use it well in service of the common good.

Some Americans might react sharply and suspect that this an example of the state overreaching itself. However, the idea of the right of the public to cross private land goes back to medieval times. It could not be enforced by the state anyway, because as explained earlier, it relies not so much on the law, but on mutual respect for its effectiveness. The way it worked was this. The landowner, perhaps the lord of the manor, agreed to allow men to farm a strip of his land to grow food in exchange for a tithe, a taxation of a tenth of the produce. The tithes were collected in huge barns – ‘tithebarns’- the photographs, above and below show one example that still exists in Oxfordshire in England. However, there was a problem. Our serf might have the land to grow his food, but if it is situated in the middle of a large estate owned by someone else, how is he going to get to it without trespassing? To overcome this, a system of pathways developed that ensured that people could get to their land without fear of prosecution. They were allowed ‘right of way’. They could cross someone else’s land provided they followed the path and respected the property. This is part of an old tradition of noblesse oblige. This is a French phrase which means literally, ‘nobility obliges’. It communicates the idea that with privilege comes the responsibility to use it well in service of the common good.

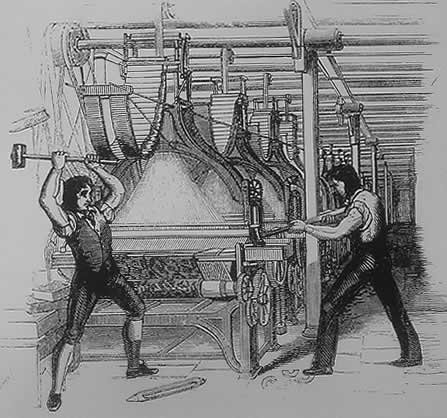

The idea of a public right of way survived, surprisingly, the industrial revolution right through to the 20th century. By the 20th century, however, many landowners were doing the best to close the paths down and stop public access. The demand for access to the land arose now not from the need to cultivate a leased strip of land, but for the desire for recreation by city dwellers, who otherwise had no chance to experience the countryside. This natural desire to be in contact with the land was being thwarted. There were mass peaceful protest walks. This resulted in Britain’s national parks being set up in which not just the paths, but the traditional beauty of the farmed landscape was protected, as well as the maintenance of traditional public footpaths throughout the whole countryside (not just within the park boundaries).

The idea of a public right of way survived, surprisingly, the industrial revolution right through to the 20th century. By the 20th century, however, many landowners were doing the best to close the paths down and stop public access. The demand for access to the land arose now not from the need to cultivate a leased strip of land, but for the desire for recreation by city dwellers, who otherwise had no chance to experience the countryside. This natural desire to be in contact with the land was being thwarted. There were mass peaceful protest walks. This resulted in Britain’s national parks being set up in which not just the paths, but the traditional beauty of the farmed landscape was protected, as well as the maintenance of traditional public footpaths throughout the whole countryside (not just within the park boundaries).

As you can imagine, I would love to see a similar system set up in the US but was told that Americans' understanding of what private ownership of land means, as well as fear of litigation is less likely to allow this. To my surprise, however, I have found out that in New Hampshire at least allows there is the possibility of such a system. By New Hampshire law, the citizens have access to any land provided they respect what is on it. The same law protects landowners from litigation if the person who goes on to his land is injured in some way. The landowner can bar people from his land if he wishes however, by ‘posting’ it – putting up a publicly displayed notice which tells people that they are trespassing and if they encroach and they will be prosecuted. Landowners exercise this option by paying a higher rate of property tax to the state.

the possibility of such a system. By New Hampshire law, the citizens have access to any land provided they respect what is on it. The same law protects landowners from litigation if the person who goes on to his land is injured in some way. The landowner can bar people from his land if he wishes however, by ‘posting’ it – putting up a publicly displayed notice which tells people that they are trespassing and if they encroach and they will be prosecuted. Landowners exercise this option by paying a higher rate of property tax to the state.

Also, I have recently seen some similar attempts working within American law in California, around the San Francisco Bay area, to create walks across pasture land rather than always 'wilderness'.

According to Catholic social teaching, land is a common good. It is created by God and all people therefore should have access to it. This would seem to mitigate against the idea of private ownership of land. However, in practice this is not the case. The best way to have a plot of land developed for the common good is to give favoured person the freedom to develop it and to exclude others only so far as they do not interfere with this. This is not a right to private property as many envisage it today, however. It is better seen as a privilege, an entitlement to develop it in accordance with the common good (and farming it for profit would qualify in this respect). In medieval times there was also ‘common’ ground, preserved for commoners who did not own the land, so that there was always somewhere for them to put their animals to pasture. Sadly, much common pasture land was seized for private ownership after the industrial revolution. There are exceptions however and Port Meadow in Oxford is one. You can walk across it today and see a charming hotchpotch of ponies, horses and cows grazing on this huge flat open expanse of grassland next to the Thames that reaches right into the city. Here in the US Boston Common exists right in the centre of the city today, admittedly as a public park and clearly it gets its name from the tradition of common pasture land. I do not know of its current status in law in regard to free pasture however. If any inner city goatherds can enlighten me in this respect, I would be grateful.

According to Catholic social teaching, land is a common good. It is created by God and all people therefore should have access to it. This would seem to mitigate against the idea of private ownership of land. However, in practice this is not the case. The best way to have a plot of land developed for the common good is to give favoured person the freedom to develop it and to exclude others only so far as they do not interfere with this. This is not a right to private property as many envisage it today, however. It is better seen as a privilege, an entitlement to develop it in accordance with the common good (and farming it for profit would qualify in this respect). In medieval times there was also ‘common’ ground, preserved for commoners who did not own the land, so that there was always somewhere for them to put their animals to pasture. Sadly, much common pasture land was seized for private ownership after the industrial revolution. There are exceptions however and Port Meadow in Oxford is one. You can walk across it today and see a charming hotchpotch of ponies, horses and cows grazing on this huge flat open expanse of grassland next to the Thames that reaches right into the city. Here in the US Boston Common exists right in the centre of the city today, admittedly as a public park and clearly it gets its name from the tradition of common pasture land. I do not know of its current status in law in regard to free pasture however. If any inner city goatherds can enlighten me in this respect, I would be grateful.

What is attractive about the medieval balance between practicalities and the preservation of land for the common good is that it allows for a blurring of the division between the two extremes of complete public access one hand and on the other a total exclusion of all those who d0 not own land.

What is attractive about the medieval balance between practicalities and the preservation of land for the common good is that it allows for a blurring of the division between the two extremes of complete public access one hand and on the other a total exclusion of all those who d0 not own land.

It may be an unrealizable dream, but nevertheless I will end by encourage all landowners to consider the idea of noblesse oblige in regard to their land. At the same time I would like to encourage citizens, if accorded this privilege, to respect the land they go on to. I am aware that the Americans' love of hunting with guns might during deer season might need thinking about if this is going to work - perhaps this might have to restrained as a condition of access in some cases - but if we can find a way of making it happen, I believe that we will have an even happier nation if we do!

Vocation and the Common Good

How doing what I want to do helps others to do what they want - a tribute to the outgoing President of the Dominican School of Theology and Philosophy in Berkeley, CA Several years ago, I attended a short lecture series offered by Fr Michael Sweeney, who was president of the Dominican School of Philosophy and Theology a member school of the Graduate Theological Union at Berkeley). It was called Re-Visioning Society and was offered as part of their summer session and explored Catholic social teaching and the common good. I am reminded of this now, in 2015, because I have stayed in touch with Fr Sweeney ever since. He has just stepped down from his role as President after 10 years. I am sure he will continue to have a profound affect people's lives in this next phase of his life. I hope also, of course, that the incoming President continues and even builds on the good work that has been going on at the school.

I was interested Fr Sweeney's course I because this idea of the common good has been referred to by Pope Benedict in a recent encyclical. What I didn't quite realize beforehand how important what I learned would be on my thinking subsequently. I was excited to realize, as happens so often when I learn more about one aspect of Catholic teaching, that it would have an impact on my understanding of everything else in the Faith. One of those in particular relates to the idea of personal vocation. I had written an article about discerning personal vocation just before this. Here is the article I wrote after the course, 5 years ago, in which (with the aid of Fr Sweeney's lectures) I hoped to place that idea of personal vocation in the context of God’s vocation for the whole human race, the common good:

How doing what I want to do helps others to do what they want - a tribute to the outgoing President of the Dominican School of Theology and Philosophy in Berkeley, CA Several years ago, I attended a short lecture series offered by Fr Michael Sweeney, who was president of the Dominican School of Philosophy and Theology a member school of the Graduate Theological Union at Berkeley). It was called Re-Visioning Society and was offered as part of their summer session and explored Catholic social teaching and the common good. I am reminded of this now, in 2015, because I have stayed in touch with Fr Sweeney ever since. He has just stepped down from his role as President after 10 years. I am sure he will continue to have a profound affect people's lives in this next phase of his life. I hope also, of course, that the incoming President continues and even builds on the good work that has been going on at the school.

I was interested Fr Sweeney's course I because this idea of the common good has been referred to by Pope Benedict in a recent encyclical. What I didn't quite realize beforehand how important what I learned would be on my thinking subsequently. I was excited to realize, as happens so often when I learn more about one aspect of Catholic teaching, that it would have an impact on my understanding of everything else in the Faith. One of those in particular relates to the idea of personal vocation. I had written an article about discerning personal vocation just before this. Here is the article I wrote after the course, 5 years ago, in which (with the aid of Fr Sweeney's lectures) I hoped to place that idea of personal vocation in the context of God’s vocation for the whole human race, the common good:

The questions I was hoping to resolve ran as follows: how can I act in ‘solidarity’ with the ‘common good’ and fulfill a personal vocation at the same time? Does acting for the common good mean that I have to think about how every action is in part, for example, going to contribute to alleviating famine in the world? Or, put another way, if I do nothing directly to help alleviate famine in Africa, am I ignoring my obligation to act in accordance with the common good? If either is so, it seems an impossibly high standard to achieve. Furthermore, won’t it likely undermine my success at doing anything well because I will have to spread myself too thinly – if I devote the time needed to teaching at Thomas More College, plus the other duties of life, I have none left to use directly to help those starving in the horn of Africa. Is this wrong? Am I being selfish in being and artist because I love doing it?

The course began by establishing from reason (as distinct from revelation) the nature of the human person as a relational being. We were simply asked to give a short summary of who we were for the other members of the class.

At this point I must admit I was wondering if I’d done the right thing in signing up for the class. Was it was going to degenerate into a touchy feely therapy? I needn’t have worried however. After allowing each of us to speak, Fr Sweeney then remarked on a common thread that ran through our descriptions of ourselves. Our own sense of ourselves was based upon relationships we have with others. (For example, ‘I work with this company’ ‘I do this job with these people’ ‘I am a father’) This is, we were told, what describes a person, as distinct from an individual. A human person is always in relation with others, starting from birth. No one, by choice, disengages from society altogether (not even a hermit) and is happy. From this starting point in common experience, he built up rationally, the case he was making, taking us with him…

This understanding of the human person has a profound effect on how we view what society is. A relationship of the sort we are now envisioning is always between two subjects ie two people freely cooperating as moral agents. This is termed covenantal and is based upon mutual self-sacrifice on behalf of the other. This freedom to respond as a person is one of the essential elements of society. Society therefore is the vector sum of the relationships within it. It is not a collective of self-contained individuals.

As with all things that exist in human nature, the essence of personhood exists in perfection in God in whose image and likeness we are made. However, there is only one God and unlike us He is complete unto Himself and does not rely on any external relationships in order to exist. Revelation helps us here: through it we know that there is one God and three persons in the Trinity, in perfectly realized relationship. This Christian concept of God also explains why we are liturgical beings, first and foremost. We are made for the liturgy, by which we approach the Father, through the Son, in the Spirit. When we participate in the liturgy we enter the Church, the mystical body of Christ. When we do so, with grace, we can relate first to the Son as man; and second to the Father through the Son as God. The Son is one person, but two natures.

If God were not like this, our relationship with him would be very different. A God who is not personal in the Christian sense would always be above us. We could not be raised to Him. Instead of a relationship of two subjects, it would be one of subject and object that is, master and slave. One can immediately see why Judeo-Christian society is fundamentally different from Islamic understanding of society, for example.

The good is what we seek and what makes us happy. We know from revelation objectively that this is God. This is the ultimate Good that is common to all of us. Society as a whole is called to be with Him in heaven and simultaneously, each person is called be with Him as well. On the way there are secondary goods that every one of us needs in order to be happy: food, shelter, water, air, love and so on. These are common goods.

So what of personal vocation and common good? God has called each of us to be with Him in heaven, as I described in my previous article, when we follow this we feel the joy that is ours. If we consider the vision that God has for society to be represented by a picture, then each personal vocation is a piece in the jigsaw that contributes to that picture. Therefore, we only need focus on our personal vocation and be content that it is contributing to the big picture and if perfectly realized would be in perfect harmony with it. This is not justifying selfishness. Every vocation is one of charity which permeates all that we do, but the precise way in which we are called to direct that charity is unique to each person. Some will be called to raise money for those who are starving. Some will not, but will be asked to. We are connected to society most profoundly through our closest personal relationships. So whatever these happen to be, these are the ones that we should focus on the most.

This of course, does rely on us being able to discern our vocation. We are fallen people and man’s ingenuity to hide bad motives behind good seems at times limitless. Therefore, good counsel is to be recommended during the discernment process.

When faced with a major choice we can ask ourselves a number of questions that help to point us in the right direction. First, is what I am doing consistent with its proper end? If so I am more likely to completing my piece of the jigsaw. Second (as a safeguard) is what I am proposing to do contrary to common good? Is it undermining others’ ability to respond freely in their relationships, for example; is it polluting the air so that it’s likely to harm those who breathe it. If so, I won’t do it.

Applied in business for example, other things being equal, I would act to make the business as profitable as possible, so that the gross profit was available to pay costs and employees, distribute amongst shareholders and reinvest for the continued profitability of the business. I would not feel obliged, for example, to institute charitable donations by the business to people that would be otherwise unconnected to the business model (although it would be perfectly good to take steps to enable shareholders and individuals to choose to contribute cooperatively in some way that they could not do as individuals). The general principle is that by fulfilling our personal vocation, we will be helping society as a whole to move towards the common good (and by refusing to do so, we tend to frustrate it).

I saying that each person's vocation is unique, what we are referring to is each person's unique way of attaining those goods that are common to all of us. And if in essence our vocation itself is common, and if the essential relationships through which it is expressed our common, then we are necessarily in solidarity with each other as we pursue our own vocation.

And what does this have to do with beauty? Beauty is what we perceive when there is harmonious relationships, sometimes called ‘due proportion’. In the context of human relationships, that is the harmonious alignment of wills on behalf of another and it is called love. An education in beauty is an education in love. It will increase our natural instinct for acting in accordance with the common good for the benefit of all. It starts with God’s love for us, already assured, and the degree to which we respond in kind, through grace.

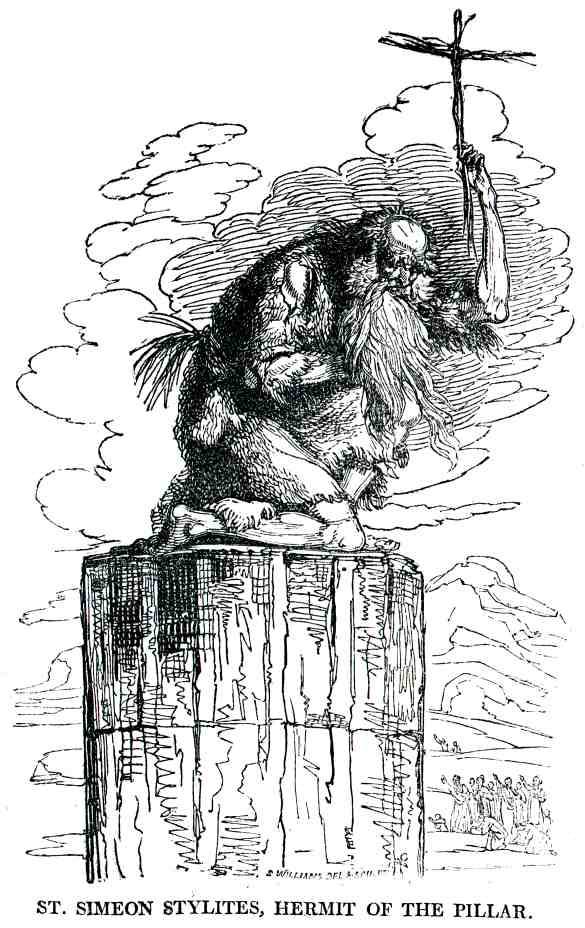

As St Augustine said: ‘Love God and do what you want.’ And even if it means going to the desert and sitting on a pillar it is helping mankind...

Discerning My Vocation as an Artist

How I came to be doing what I always dreamed of

How I came to be doing what I always dreamed of

Following on from the last piece, as mentioned I am reposting an article first posted about four years ago. In connection with that, it is worth mentioning that one's personal vocation can change as we grow older. I am not necessarily set in the same career or life situation for life. What was fulfilling for me as a young man may not be right for me now. So I do think that regular reassessment is something that should be considered.

I wrote this originally because people regularly ask me how they can become an artists. One response to this is to describe the training I would recommend for those who are in a position to go out and get it. You can read a detailed account of this in the online course now available. However, this is only part of it (even if you accept my ideas and are in a position to pay for the training I recommend). It was more important for me first to discern what God wants me to do. I did not decide to become an artist until I was in my late twenties (I am now 52). That I have been able to do so is, I believe, down to inspired guidance. I was shown first how to discern my vocation; and second how to follow it. I am not an expert in vocational guidance, so I am simply offering my experience here for others to make use of as they like.......

I am a Catholic convert (which is another story) but influential in my conversation was an older gentleman called David Birtwistle, who was a Catholic. (He died more than ten years ago now.) One day he asked me if I was happy in my work. I told him that I could be happier, but I wasn’t sure what else to do. He offered to help me find a fulfilling role in life.

He asked me a question: ‘If you inherited so much money that you never again had to work for the money, what activity would you choose to do, nine to five, five days a week?’ One thing that he said he was certain about was that God wanted me to be happy. Provided that what I wanted to do wasn’t inherently bad (such as drug dealing!) then there was every reason to suppose that my answer to this question was what God wanted me to do.

While I thought this over, he made a couple of points. First, he was not asking me what job I wanted to do, or what career I wanted to follow. Even if no one else is in the world is employed to do what you choose, he said, if it is what God wants for you there will be way that you will be able to support yourself. He told me to put all worries about how I would achieve this out of my mind for the moment. Such doubts might stop me from having the courage to articulate my true goal for fear of failure. Remember, he said, that if God’s wants you to be Prime Minister, it requires less than the ‘flick of His little finger’ to make it happen. If wanted to do more than one thing, he said I should just list them all, prioritise them and then aim first for the activity at the top of the list.

I was able to answer his question easily. I wanted to be an artist. As soon as I said it, I partly regretted it because the doubts that David warned me about came flooding in. Wasn’t I just setting myself up for a fall? I had already been to university and studied science to post-graduate level. How was I ever going to fund myself through art school? And even if I managed that, such a small proportion of people coming out of art school make a living from art. What hope did I have? I worried that I would end up in my mid-thirties a failed artist with no other prospects. David reassured me that this was not what would happen. This process did not involve ever being reckless or foolish, but I would always need faith to stave off fear.

I was able to answer his question easily. I wanted to be an artist. As soon as I said it, I partly regretted it because the doubts that David warned me about came flooding in. Wasn’t I just setting myself up for a fall? I had already been to university and studied science to post-graduate level. How was I ever going to fund myself through art school? And even if I managed that, such a small proportion of people coming out of art school make a living from art. What hope did I have? I worried that I would end up in my mid-thirties a failed artist with no other prospects. David reassured me that this was not what would happen. This process did not involve ever being reckless or foolish, but I would always need faith to stave off fear.

Next David suggested that I write down a detailed description of my ideal. He stressed the importance of crystallizing this vision in my mind sufficient to be able to write it down. This would help to ensure that I spotted opportunities when they were presented to me. Then, always keeping my sights on the final destination, I should plan only to take the first step. Only after I have taken the first step should I even think about the second. Again David reiterated that at no stage should I do anything so reckless that it may cause me to let down dependants, to be unable to pay the rent or put food on the table.

The first step, he explained, can be anything that takes me nearer to my final destination. If I wasn’t sure what to do, he told me to go and talk to working artists and to ask for their suggestions. There are usually two approaches to this: either you learn the skills and then work out how to get paid for them; or even if you have to do something other than what you want, you put yourself in the environment where people are doing it. For example, he suggested that I might get a job in an art school as an administrator. My first step turned out to be straighforward. All the artists I spoke to told me to start by enrolling for an evening class in life drawing at the local art school.

My experience since has been that I have always had enough momentum to encourage me to keep going. To illustrate, here’s what happened in that first period: the art teacher at Chelsea Art School evening class noticed that I liked to draw and suggested that I learn to paint with egg tempera. I tried to master it but struggled and after the class was finished I told someone about this. He happened to know someone else who, he thought, worked with egg tempera. He gave me the name and I wrote asking for help. About a month later I received a letter from someone else altogether. It turned out that the person I had written to was not an artist at all, but had been passed the letter on to someone who was called Aidan Hart. Aidan was an icon painter. It was Aidan who wrote to me and who invited me to come and spend the weekend with him to learn the basics. Up until this point I had never seen or even heard of icons. Aidan eventually became my teacher and advisor.

There have been many chance meetings similar to this since. And over the course of years my ideas about what I wanted to do became more detailed or changed. Each time I modified the vision statement accordingly, and then looked out for a new next step – when I realized that there was no school to teach Catholics their own traditions, I decided that I would have to found that school myself and then enlist as its first student. Later it dawned on me that the easiest way to do thatwas to learn the skills myself from different people and then be the teacher.

There have been many chance meetings similar to this since. And over the course of years my ideas about what I wanted to do became more detailed or changed. Each time I modified the vision statement accordingly, and then looked out for a new next step – when I realized that there was no school to teach Catholics their own traditions, I decided that I would have to found that school myself and then enlist as its first student. Later it dawned on me that the easiest way to do thatwas to learn the skills myself from different people and then be the teacher.

I was also told that there were two reasons why I wouldn’t achieve my dream: first, was that I didn’t try; the second was that en route I would find myself doing something even better, perhaps something that wasn’t on my list now. When this happens you will be enjoying so much you stop looking further.

David also stressed how important it was always to be grateful for what I have today. He said that unless I could cultivate gratitude for the gifts that God is giving me today, then I would be in a permanent state of dissatisfaction. In which case, even if I got what I wanted I wouldn't be happy. This gratitude should start right now, he said, with the life you have today. Aside from living the sacramental life, he told me to write a daily list of things to be grateful for and to thank God daily for them. Even if things weren’t going my way there were always things to be grateful for, and I should develop the habit of looking for them and giving praise to God for his gifts. He also stressed strongly that I should constantly look to help others along their way.

As time progressed I met others who seemed to be understand these things. So just in case I was being foolish I asked for their thoughts. First was an Oratorian priest. He asked me for my reasons for wanting to be an artist. He listened to my response and then said that he thought that God was calling me to be an artist. Some years later, I asked a monk who was an icon painter. He asked me the same questions as the Oratorian and then gave the same answer.

What was interesting about all three people so far is that none of them asked what seemed to be the obvious question: ‘Are you any good at painting?’ I asked the monk/artist why and he said that you can always learn the skills to paint, but in order to be really good at what you do you have to love it.

Some years later still, when I was studying in Florence, I went to see a priest there who was an expert in Renaissance art. It was for his knowledge of art that I wanted to speak to him, rather than spiritual direction. I wanted to know if my ideas regarding the principles for an art school were sound. He listened and like the others encouraged me in what I was doing. Three years later, after yet another chance meeting, I was offered the chance to come to Thomas More College of Liberal Arts in New Hampshire, to do what precisely what I had described to the priest in Florence.

In my meeting with him the Florentine priest remarked in passing, even though I hadn’t asked him this, that he thought that it was my vocation to try to establish this school. He then said something else that I found interesting. He warned me that I couldn’t be sure that I would ever get this school off the ground but he was certain that I should try. As I did so, my activities along the way would attract people to the Faith (most likely in ways unknown to me). This is, he said, is what a vocation is really about.

Come Out of the Wilderness and into the Garden

The garden is the symbol of the culture of life

Gardens and farmland are more natural and more beautiful than pristine, untouched wilderness. Or at least they should be.

Of course the wilderness is beautiful. I am not trying to change anyone's view on that. But I am seeking to raise the status of cultivated land relative to it. The assumption of most conservationists today seems to be the opposite. In fact, my experience is that for many if there is an objective standard of beauty, it is nature unaffected by man.

This is consistent with a neo-pagan worldview. Many people even take this idea - that man is inferior to untouched nature - a step further and consider man not to be part of nature at all. The work of mankind is assumed to be unnatural …by nature (if you’ll forgive the phrase, but it does seem to highlight the absurdity of the position). Man's activity is seen as something that necessarily defaces creation. This places wilderness above gardens and farmland in the hierarchy of beauty; and above man in the hierarchy of being.

In the Christian worldview, man is the greatest creature in God’s creation. Man is not only part of creation, but his work can act to perfect it, that is to restore a fallen world to what it ought to be. To the degree that he works in harmony with the divine order (which is a standard higher than anything in the created world) his work is beautiful, productive and in harmony with the common good; and nature flourishes. This is the true ecology.

As soon as one acknowledges the possibility of man perfecting nature, then the route to a ‘green’ world is not the restriction of human activity, but an increase in the right sort of activity. If one seeks to change the form of human activity so that it is working beautifully, in harmony with the divine order, then the more people there are, the better.

The neo-pagan worldview, on the other hand, cannot conceive of this restorative human interaction with creation. His activity is just more or less destructive. The only solution therefore that it has to propose is the reduction of all human activity. There is only one really effective way to do this – population control.

In some ways, it is not surprising that this secular, neo-pagan world view predominates. Many would look at man’s work, especially of the last 100 years, and see destruction and ugliness. This is, it seems to me, just another reflection of modern culture, along with the art, the music, architecture and so on. And the solution is the same. The via pulchritudinis is as much the answer to the culture of death as it is the culture of ugliness.

I believe that when man cultivates the land and farms beautifully, then it is in harmony with the natural world and everything including wildlife flourishes in those parts that are left; the food produced is of a greater variety, healthier and tastier and it is produced in abundance. A discussion of farming methods is ultimately one about economics. This should be no surprise. Economics and business are a reflection of the culture as much as high art. However, this is beyond the scope of this short article. I have included, though, a picture of myself out for a walk in the Shropshire countryside in England. This landscape was formed by centuries of sympathetic farming (although one wonders how much longer it will be maintained). I could have as easily picked out a photograph of Tuscany , Provence, Granada or any small farm in New Hampshire (although these are disappearing fast).

This article is in praise of gardening. Unlike farming, there is no need to discuss economics. Anyone with the smallest plot of land can create a beautiful garden as anyone who has visited England will know (England is a land of beautiful gardens). when I talk of gardens, I am talking here of the cultivation of land for beauty, rather than for food. If farming is the Martha of man’s relationship with nature, gardening is the Mary. Adam was the first gardener in Eden. I would love to see the adoption of beautiful gardens as a modern symbol of a true ecology where man works with nature to restore Eden!

The traditional European model of the garden is geometric in form. I always imagine that the cloistered pathway into the church, should look onto the cloistered garden which is a re-creation Eden and a preparation for entering the church, which should evoke heaven. It should be the place in which man elevates the natural world, through God’s grace, into the highest and most beautiful form he is capable of producing. The picture shown above is of a cloistered garden, not in a monastery but in a stately home in Wales. Although simple (I had hoped to find something more ornate, but couldn't) it is still beautiful I think.

The English tradition of the landscaped garden arose in the 17th century in imitation of paintings by the baroque masters of rural idylls in the neo-classical tradition. So for example we see a painting by the 17th-century French landscape painter Claude Lorrain and a garden designed by Capability Brown at Stourhead in Wiltshire, England. There is even a ‘folly’ (a building that has no utility other than its place in the view) which mimics the Roman Pantheon.

The English tradition of the landscaped garden arose in the 17th century in imitation of paintings by the baroque masters of rural idylls in the neo-classical tradition. So for example we see a painting by the 17th-century French landscape painter Claude Lorrain and a garden designed by Capability Brown at Stourhead in Wiltshire, England. There is even a ‘folly’ (a building that has no utility other than its place in the view) which mimics the Roman Pantheon.

My parents were avid gardeners who cultivated the back garden in the tradition of the English cottage garden. They are now retired and live in southern Spain (along with a host of British ex-pat retirees). Many English people recreate this style in the gardens of their villas in Malaga region. It is a year-round watering job just to keep the lawn, the tulips and petunias alive. My mum and dad, on the other hand, decided to use a similar design to their English garden, based upon foliage colours of shrubs and perennials, but by making use of indigenous species. Consequently, it thrives with a fraction of the watering. Mention this just to make the point that wherever you are, there plants that grow well and which can be ordered in a beautiful way. So you can plant your monastic cloistered cactus garden in Arizona, starting today!

Public Access to Farmland...in the San Francisco Bay Area

Holy cow! Its just like going for a walk in England! In my recent trip to California I decided to investigate the footpaths in the area. As usual, I tried to find the countryside that is the most beautiful - farmland - and expected to be able to indulge in my favorite complaint: how all paths in the US are in specially created parks that aim to create the 'wilderness' experience, which means that you spend the whole day walking through forest, unable too anything further than the nearest tree trunk. To my surprise, I found that there are plenty of areas of beautifully farmed land to which the public has access.

Holy cow! Its just like going for a walk in England! In my recent trip to California I decided to investigate the footpaths in the area. As usual, I tried to find the countryside that is the most beautiful - farmland - and expected to be able to indulge in my favorite complaint: how all paths in the US are in specially created parks that aim to create the 'wilderness' experience, which means that you spend the whole day walking through forest, unable too anything further than the nearest tree trunk. To my surprise, I found that there are plenty of areas of beautifully farmed land to which the public has access.

In Britain, in common with most European countries, there is no wilderness left and the countryside is privately owned farmland. This doesn't stop people being able to feel a connection with the land and enjoy it, however, for there is widespread public access to private land. It is the remnant of the traditional Catholic understanding of land as a 'common good'. If you are surprised by this you can read about exactly how in an earlier article Farms, Country Walks, Private Property and the Common Good. I enjoy farmland because it is more beautiful than the wilderness, if farmed well. The New World obsession with the 'wilderness experience' as exposure to pristine beauty (strongest of all in New Zealand in my experience) is a reflection of the New Age paganism, which sees man as an unnatural influence on a perfect Nature, rather than a positive influence that raises a fallen world up to something greater.

It is the same worldview that gives rise to the culture of death. When the activity of man is viewed as necessarily unnatural, then human activity is seen as something that should be limited. The easiest way to do so is to enforcing population control; and the obvious ways to achieve this are abortion and contraception.

It is the same worldview that gives rise to the culture of death. When the activity of man is viewed as necessarily unnatural, then human activity is seen as something that should be limited. The easiest way to do so is to enforcing population control; and the obvious ways to achieve this are abortion and contraception.

As well as contributing to making my visit to the Bay Area very enjoyable, these parks are a small symbol of hope for me. I visited two areas. The first is called Briones Regional Park. I am always curious as to why we are allowed onto this land. This is preserved as pastureland because it is the watershed lands that fill the reservoirs that supply water to much of the region. The regional government that leases the land, as I understand it, insists also that there is public access. Trees would suck up too much water so the land is kept for pasture. It has been ranched for about 200 years (since the Spanish colonial days) and so the terrain has been formed by that. At this time of year there is a lot of rain and so everything is lush and green - even the locally produced descriptions remark on how like English countryside it looks.

The second area is called Lucas Valley and it is in Marin County which is north of the Golden Gate bridge. Much of the valley is own by the film producer George Lucas, but I am told that the matching names are coincidence. What is interesting about this is that we have an arrangement forged between private landowners so that people can enjoy the scenery. I know this because at he beginning of the walk I saw the following notice (perhaps noblesse oblige isn't dead after all!):

So here are some photos of the walk. First Briones Regional Park in the East Bay:

The second area is Lucas Valley.

In the height of spring both of these areas will be filled with wild flowers. It is a little early for the full display, but I took some snaps of some of those that I saw as well.

A Walk in Wales, Seeing an Ancient Roman Aqueduct

When I did my summer trip, after seeing my parents in Spain I went to stay in England and the area where I grew up (a little town near Chester called Neston). As well as seeing friends and family there I wanted to re-establish my connection with the familiar places and especially the walks and the countryside that I remembered from when I lived there (not all that long ago - I don't want to sound too whistfully romantic here!). Neston is near the border with Wales, which is rural and hilly.

Just to give you a sense of the place, I thought I would post some photos of one of these walks; but also there are interesting parallels here between this walk and one that I did in Spain (I wrote about this in an article posted on 6th July). First is the existence of laws of 'right to roam' and 'public right of way' on private land. In the UK there are public footpaths across farmland, which require the farmer to maintain for the common good. Second and even more specifically, for part of this walk, one of the reasons for this public access is that we can follow the line of an old aqueduct. The idea of the common good and access to private land here.

When I did my summer trip, after seeing my parents in Spain I went to stay in England and the area where I grew up (a little town near Chester called Neston). As well as seeing friends and family there I wanted to re-establish my connection with the familiar places and especially the walks and the countryside that I remembered from when I lived there (not all that long ago - I don't want to sound too whistfully romantic here!). Neston is near the border with Wales, which is rural and hilly.

Just to give you a sense of the place, I thought I would post some photos of one of these walks; but also there are interesting parallels here between this walk and one that I did in Spain (I wrote about this in an article posted on 6th July). First is the existence of laws of 'right to roam' and 'public right of way' on private land. In the UK there are public footpaths across farmland, which require the farmer to maintain for the common good. Second and even more specifically, for part of this walk, one of the reasons for this public access is that we can follow the line of an old aqueduct. The idea of the common good and access to private land here.

The Spanish aqueduct was built by the Moors, this one was built by the Romans. The Spanish one was in a good state of repair and still used to irrigate olive groves, this has fallen into disrepair and is now a toepath along a muddy ditch in the woods because it is not needed for water any more. My guess here, because you don't need irrigation channels in rainy rural Wales, is that the Roman aqueduct would be used to provide drinking water for a town, perhaps Chester (Roman name Deva). Drinking water supplies have changed - no longer would people drink redirected stream water taken from a mountainside and so there is no reason to have kept it operable.

As you follow the path described below, remember this: the enjoyment and direct contact with farmland and farm animals is possible because of what remains of the traditional application of an idea that comes from Catholic social teaching, that land is a common good. We are crossing privately owned land, but still in the UK there is the understanding that with that privelege comes the responsibility of making it available to all in as way that doesn't stop the owner from cultivating it.

So the first step was for my friend Jim and I to take the car up to a ridge on the Clwyd hills in Wales (pronounced 'clue-id'):

From there the ridge path goes off in two directions, one through grazing sheep:

And the other up a more developed path that takes you up to the highest point on the ridge, Moel Famau (pronounced 'mole vamma') a mountain about 2,000 ft above sea level, so not very high. We took this one. It's a popular destination so the path is well maintained:

The terrain here is, like the whole of Britain, man created. In this particular area, sheep grazing stops the growth of trees, and this hilly terrain is low woody plants of dark heather (which has bright purple flowers) and lighter billberry (a small and not-so-sweet version of the American blueberry) grows wild here.

As we look down into the lower parts, some copses and naturally growing trees are allowed to remain, but much of the wooded area is planted for commercial reasons, for wood. There are also bare patches where the trees have been harvested and no ground cover has yet grown.

After several miles we turn right, climb over a stile and down into the valley below. The gate to left which can be raised is for people to walk their dogs through.

We gradually descend until we hit a level part in the valley below:

We continue until we descend again into a tree-filled broad gully. This has a stream running it, and running parallel above it, but still in this wooded gully, the aqueduct. This is known locally as 'the Leet' (or 'Lete'). I do not know why it has this name.

When we hit the Lete we turn left and walk along the gully alongside it for about two miles.

It looks like this for about another two miles until we emerge into farmland and little village called Cilcain. We stop at the pub for lunch. The red, white and blue balloons are there because this was the Monday after the recent Jubilee celebrations of Queen Elizabeth II's reign.

And we admire the cottage gardens across the road from where we sat eating sandwiches and drinking coffee.

Then we headed out of the village back up to the ridge from where we first descended, through low hills first, past grazing sheep again, then on to the ridge itself, now several miles further along from where left it this morning.

And once at the ridge path, we turned left once more, to complete the final phase of the circular walk along the ridge and back to the car.

Footnote: if anyone who is not used to the spelling of Welsh words found the pronunciation of 'Clwyd' difficult to fathom, then have a go at this name of this place, also in north Wales (it really is a genuine place name):

It is the railway station in the town of 'Llanfair p g'. I grew up in England so wasn't native Welsh speaker at all. However, we used to enjoy learning and then reeling off the pronunciation as party trick. For the curious, this what it sounds like:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=taUJDmajoaY&feature=related

A walk along an ancient aqueduct in southern Spain

When I was in Spain in May, some neighbours of my parents offered to take me on a walk that followed the line of an ancient aqueduct built by the Moors centuries ago. Phil and Brenda took me to a spectacular route that started in the town of Canillas (about an hour from Malaga). The aqueduct was a small channel providing water for irrigation and drinking water for the town. It is about a foot square in cross section and open topped. It weaves its way around the hills through olive groves and wild flower meadows, climbing at a rate only slightly greater than a contour line. This lead us eventually up high into a fast running stream in a narrow gorge, which was the source of the water.What was interesting was that this was still the means of irrigating the olive groves on the hillside. So in some sections, where the Moorish stonework had begun to leak, the channel had been mended. Somtimes with stone and cement, and sometimes even with sections of black plastic pipeline. From time to time, there would be small sluice gates that could be dropped into the channel, blocking it off and then directing the water onto the fields below that section.

I have spoken in the past, here, about how there is a 'right to roam' in European countries. It's exact form takes different shapes, but for the most part, provided you don't take produce or destroy property and respect the land and personal rights of those who own it, you are entitled to go onto privately owned land. It means that in Europe that those who live in cities and suburbs and are not landowners, nevertheless have access to the land and have a sense of connection with it. People can also experience the peace and see the beauty of well managed agricultural land which has a very different effect on the soul than seeing 'wilderness' - land unaffected by man. New-world countries, such as America, Australia and New Zealand do not have such laws and so it is much more difficult to get access to agricultural land (as opposed to wilderness parks). Ironically, this means that even in New Zealand, a country in which perhaps 30% of the land is preserved as national parkland, there is still a greater sense of being deprived of contact with the land than you would have in a western European country. The reason for the difference between old and new worlds is that the new societies, driven by Enlightenment ideas of individualism that started to take hold in the 18th century rejected the traditional idea, which comes from Catholic social teaching, of land being a 'common good'. The traditional idea is that landowners balance their privelege of ownership, which is necessary so that the land can be cultivated in an ordered way, with certain responsibilities towards the community as a whole.

When I was in Spain in May, some neighbours of my parents offered to take me on a walk that followed the line of an ancient aqueduct built by the Moors centuries ago. Phil and Brenda took me to a spectacular route that started in the town of Canillas (about an hour from Malaga). The aqueduct was a small channel providing water for irrigation and drinking water for the town. It is about a foot square in cross section and open topped. It weaves its way around the hills through olive groves and wild flower meadows, climbing at a rate only slightly greater than a contour line. This lead us eventually up high into a fast running stream in a narrow gorge, which was the source of the water.What was interesting was that this was still the means of irrigating the olive groves on the hillside. So in some sections, where the Moorish stonework had begun to leak, the channel had been mended. Somtimes with stone and cement, and sometimes even with sections of black plastic pipeline. From time to time, there would be small sluice gates that could be dropped into the channel, blocking it off and then directing the water onto the fields below that section.

I have spoken in the past, here, about how there is a 'right to roam' in European countries. It's exact form takes different shapes, but for the most part, provided you don't take produce or destroy property and respect the land and personal rights of those who own it, you are entitled to go onto privately owned land. It means that in Europe that those who live in cities and suburbs and are not landowners, nevertheless have access to the land and have a sense of connection with it. People can also experience the peace and see the beauty of well managed agricultural land which has a very different effect on the soul than seeing 'wilderness' - land unaffected by man. New-world countries, such as America, Australia and New Zealand do not have such laws and so it is much more difficult to get access to agricultural land (as opposed to wilderness parks). Ironically, this means that even in New Zealand, a country in which perhaps 30% of the land is preserved as national parkland, there is still a greater sense of being deprived of contact with the land than you would have in a western European country. The reason for the difference between old and new worlds is that the new societies, driven by Enlightenment ideas of individualism that started to take hold in the 18th century rejected the traditional idea, which comes from Catholic social teaching, of land being a 'common good'. The traditional idea is that landowners balance their privelege of ownership, which is necessary so that the land can be cultivated in an ordered way, with certain responsibilities towards the community as a whole.

In Britain, which is a land of walkers (perhaps because the temperate climate is so condusive to it) there is a modern application of the custom, which has resulted in a network of public footpaths across its length and breadth. My guides Phil and Brenda, who were great company for the day, explained to me that because so many Brits live permanently in Spain now (about three quarters of a million), that the Spanish government has begun to establish British style footpaths through scenic areas and promote them to attract yet more people as tourists. Its not clear whether the Spanish people themselves are yet as enthusiastic about walking. It seems that perhaps Noel Coward was right, only mad dogs and Englishmen go out in the midday sun.

An irrigation channel seems to me an example of a project that is intended for the common good and requires each landowner to acknowledge this in allowing it to be built on his land and in the way in which he uses it. Once this was built if the landownder wanted to act against the common good he could and use all the water for himself: nobody below him would be able to stop him taking it. Taking what is necessary for himself is in accordance with the common good, because this is how he grows food for the community (which includes himself of course). Maybe a historian out there could help me, but I don't think this would have been built by the central government buying the land through compulsory purchase order on the land. My guess is that there has been a cooperative process between landowners.

Any, enough of the discussion, here's the walk - we start by filling up the water bottles at the public drinking fountain:

And then gradually climb our way up, through olive groves and some pine groves, pausing occasionally to look back at the town below. In time the trees clear and we can see the gorge ahead.

Here, below, is a sluice gate (it's on the end of the chain only partly visible). This is a simple metal plate which is dropped into the channel at this point, directing the water out through the opening which is visible above the waterline, bottom, left. This allows the farmer who owns this part of the land to irrigate his olive groves in the hillside below. We would see these periodically as we climbed. Clearly, there is mutual trust here and an assumption that no single landowner is going to abuse the privelege of access to the water and deprive everyone else of a share. Subsequent photos show the flourishing olive groves (note how the hillside is stepped to enable access when the olives are to be picked).

Round a corner, below, and things take a turn for the spectacular:

We can see the gorge in the distance which is the source of the water for the aqueduct, you can see the it cutting across the hillside halfway up on the left:

If we walk on an turn back, we can see, below, how precarious the path is in some places:

On the photo above you can see the aqueduct cut into the cliff face on the near part. In the distance to the left you can make out the line of the road through the hills, which follows the old Moorish trading route through southern Spain. It is seen more clearly in this photo:

Then we walk up into the gorge and to the mountain stream that is the source of water:

The very start of the aqueduct is on the left in the photo above. The manmade channel has water running in it, but it is not obvious in the photographs because it is so clear.

We stopped for a drink of water at a small waterfall in the stream above this point:

And then returned to Canillas retracing our steps. The day ended with a late lunch in the village square: Spanish coffee, which is a strong and milky, and tapas.

Cardinal Virtue - A Suggestion for a New Symbol from the Book of Nature

Inspired by Rural New England I have said before how if a tradition is to be a living tradition it should be developing re-applying its core principles so that it speaks of and to each successive generation. Accordingly, we should start to look for symbolism in the light of what we now know about the natural world today. So here’s a challenge to readers. Try to think of examples that could be developed. To my mind, this should have at its root a commonly believed truth about the thing itself so that the symbolism has a natural connection with reality. Also, if the object itself is attractive it will arouse an interest regardless of what it symbolizes. For example, contrary to the belief of late antiquity, the peacock’s flesh does decay and so it is not a good symbol for immortality in today’s world. Nevertheless, the sheer attractiveness of a peacock in mosaics and paintings makes me want to find a way of including it anyway!

So in line with this here is my offering: a regular flash of red in the New England countryside is the male cardinal bird, the name is derived from the comparison to a cardinal’s robes. I was told recently that the cardinal bird interesting in that although it looks very bright when it is in its setting, when you see it in close-up and in isolation it appears relatively drab, given what a flash of colour it is when you see it at a distance. I speculate that the reason for this is that red and green are complementary colours. Red looks redder when it is next to green; just as green looks greener next to red. So the male cardinal bird is more attractive when in its natural setting. As an artist, if I paint a landscape, I always try to put some discreet strokes of red somewhere next to the green if I wish to make the foliage more vibrant.

Inspired by Rural New England I have said before how if a tradition is to be a living tradition it should be developing re-applying its core principles so that it speaks of and to each successive generation. Accordingly, we should start to look for symbolism in the light of what we now know about the natural world today. So here’s a challenge to readers. Try to think of examples that could be developed. To my mind, this should have at its root a commonly believed truth about the thing itself so that the symbolism has a natural connection with reality. Also, if the object itself is attractive it will arouse an interest regardless of what it symbolizes. For example, contrary to the belief of late antiquity, the peacock’s flesh does decay and so it is not a good symbol for immortality in today’s world. Nevertheless, the sheer attractiveness of a peacock in mosaics and paintings makes me want to find a way of including it anyway!

So in line with this here is my offering: a regular flash of red in the New England countryside is the male cardinal bird, the name is derived from the comparison to a cardinal’s robes. I was told recently that the cardinal bird interesting in that although it looks very bright when it is in its setting, when you see it in close-up and in isolation it appears relatively drab, given what a flash of colour it is when you see it at a distance. I speculate that the reason for this is that red and green are complementary colours. Red looks redder when it is next to green; just as green looks greener next to red. So the male cardinal bird is more attractive when in its natural setting. As an artist, if I paint a landscape, I always try to put some discreet strokes of red somewhere next to the green if I wish to make the foliage more vibrant.

Part of what inspired me to become a Catholic was the inspiring vision of the Church that each of us has a unique role to play in contributing to the common good. This is our personal vocation. We are most fully ourselves and so most joyful and most fulfilled when we live this calling. The joy we feel is radiant and will attract curiosity I was lucky 20 years ago in that I was given very good guidance that set me out on a journey to be doing what I have always wanted to do, I have written about this here.

I had always thought of the discovery of this as finding the right shaped hole in the jigsaw so that it helps to complete the picture that is the common good. But in fact this image of the cardinal bird says it so much more clearly. When we in the right role in relation to other and the mystical body of Christ, our own natural setting, just like the cardinal bird we become brighter and more radiant examples of the Faith.

Below: a detail from Constable's The Hay Wain showing a discreet use of red to enhance the greenness of the scene.

Another Way to Determine Your Personal Vocation

Determining Personal Gifts In order to lead a happy life it is very important, it seems to me, to be true to your personal vocation. I have written before, here, about the advice that I was given over 20 years ago, which opened up the way for me to a wonderful life.

The guidance I was given focused strongly on what to do: what is picture of perfect happiness that I envisage for myself? What job, life situation and so on does God intend for me? Having set out this vision, by ordering my activities so that gradually I move towards it, I found that I developed the skills and discovered that I had the gifts necessary to make it happen.

Determining Personal Gifts In order to lead a happy life it is very important, it seems to me, to be true to your personal vocation. I have written before, here, about the advice that I was given over 20 years ago, which opened up the way for me to a wonderful life.

The guidance I was given focused strongly on what to do: what is picture of perfect happiness that I envisage for myself? What job, life situation and so on does God intend for me? Having set out this vision, by ordering my activities so that gradually I move towards it, I found that I developed the skills and discovered that I had the gifts necessary to make it happen.

There is another way of discerning personal vocation that I have discovered recently. This came through my contact with Fr Michael Sweeney, the head of the Dominican School of Philosophy and Theology in Berkeley, California, when I attended a course there that discussed the idea of personal vocation contributing to the overall mission of the Church, the common good.

His focus is on discerning our gifts and special skills, and works on the assumption that if we then seek to employ these in our lives, bit by bit we will be guided towards the appropriate theatre in which to apply them. Each of us has a calling that is our personal contribution to the common good. Every person therefore is given a unique set of gifts by the Holy Spirit – charisms he called them – that will enable us to fulfill that vocation and so lead of life Christian joy. When we exercise those gifts we do so with a special authority as assigned to our unique position with the Church, in my case it is the Lay Office. These gifts can be things we often associate with the lives of the saints – for example the gift of leading a life of poverty for the greater glory of God. Or they can be very practical things: art, music, writing or teaching. They can also be special skills that those of us who don’t have them find it difficult to imagine anyone feeling fulfilled doing, such as the charism of administration. In connection with this, one of the things that struck me about St Ignatius of Loyola is that after he created the Jesuit order he spent most of his time quietly in Rome administering the growth of his organization. Other Jesuits, such as St Francis Xavier, were the great missionaries of the organization.

When I became a Catholic one of the things that attracted me to the Faith was the belief that this offered the way to greatest happiness. My friend David who was instrumental in bringing me into the Church always stressed how certain he was that God wanted me to be happy. When I got into the Church I realized, judging from the way they talk about their lives and their faith that not all faithful Catholics are aware of this. I have never subscribed to a view that life is something that we put up with while we await eternal bliss in heaven. Rather, eternal life starts here and now and by degrees we can experience that heavenly form of existence in this life (though not fully until we die).

When I became a Catholic one of the things that attracted me to the Faith was the belief that this offered the way to greatest happiness. My friend David who was instrumental in bringing me into the Church always stressed how certain he was that God wanted me to be happy. When I got into the Church I realized, judging from the way they talk about their lives and their faith that not all faithful Catholics are aware of this. I have never subscribed to a view that life is something that we put up with while we await eternal bliss in heaven. Rather, eternal life starts here and now and by degrees we can experience that heavenly form of existence in this life (though not fully until we die).

Intrigued by what I heard from Fr Sweeney I decided to go investigate further. Before he moved to Berkeley, Fr Sweeney was working as head of the organization that he founded to enable people to discern these gifts, the Catherine of Siena Institute. I ordered from the Institute their Called and Gifted series of recorded talks. In these Fr Michael and the co-founder Sherri Weddell describe how we can determine these gifts. I recommend them.

As described in the recorded talks, the characteristic of a charism is that it gives you special abilities that achieve great observable results, that are for the good of others and exercising these gifts feels easy and natural (although it may seem extraordinary to others who see the results). Most importantly, when exercising these charisms, we feel fulfilled. The Catherine of Siena process of discerning charisms (and you can have more than one) involves a guided examination of one’s past experience for signs of the workings of a charism. These gifts can be in very practical things, such as art, music or craftsmanship. They can be in more intellectual pursuits such as teaching or learning. They can also be in what we would probably more commonly associated with the word ‘charismatic’ in the context of the Church, such as a gift of evangelization.

I should declare hear that I have never been attracted to what I have seen of what is commonly referred to as charismatic Christianity, Catholic or otherwise. It always seems to me that there is too much emphasis on emotion and not enough on reason. What appeals to me in this approach to discerning them is that it is systematic and rational. There is no arm waving (with or without tambourine) or hysteria.

As a result of this process, it has not changed the my life direction particularly. I was not expecting this as I already feel that I am doing what want to do. However, it has changed my sense of how I should aim to achieve what I want to do. It has been revealing and helpful to me.

Also, it has immediately made more conscious of differing individual strengths and weaknesses. I can see now why I find some things very easy that others find difficult and so I can see that I ought to be more understanding when dealing with them. Similarly, it has made me less frustrated at myself in other respects. It has been obvious to me that there are things that seem to come naturally to so many people. It increases my awareness, I feel, that we all need each other to cooperate in working towards the common good.

I close with a quote from St Cyril of Jerusalem. What he says applies to all charisms, not just those he mentions specifically. It comes from the Office of Readings Monday Week 7 Eastertide, a few days before Pentecost: