A large painting 9 ft x 8 ft that is now behind the altar in the school chapel.

Some More about Henry Wingate, his work and the traditional style he paints in

Continuing in the tradition of the Boston School of portraitists, and the baroque.

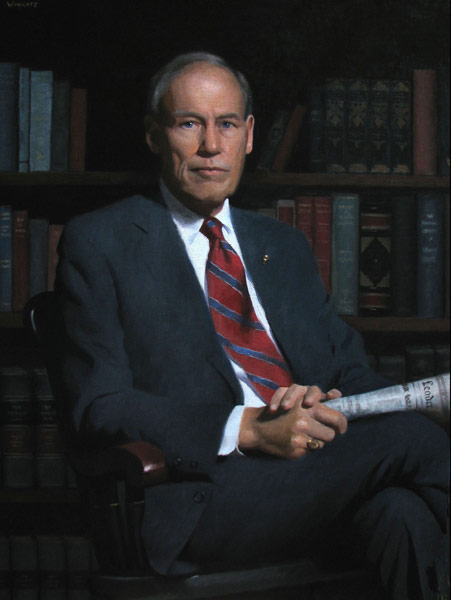

Following on from the last post, I thought that readers might be interested to see some more work of artist Henry Wingate, and to know more about the academic method that he uses to such great effect. I like his portraits especially and he is one of relatively few artists around today who is making a real contribution to a re-establishment of traditional principles by teaching as well as painting (motivated by a desire to serve the Church).

Continuing in the tradition of the Boston School of portraitists, and the baroque.

Following on from the last post, I thought that readers might be interested to see some more work of artist Henry Wingate, and to know more about the academic method that he uses to such great effect. I like his portraits especially and he is one of relatively few artists around today who is making a real contribution to a re-establishment of traditional principles by teaching as well as painting (motivated by a desire to serve the Church).

Based in rural Virginia, Wingate studied with Paul Ingbretson in New England and with Charles Cecil, in Florence, Italy. Both Ingbretson and Cecil studied under R H Ives Gammell, the teacher, writer, and painter who perhaps more than anyone else kept the traditional atelier method of painting instruction alive.

The academic method was first developed in Renaissance Italy and was the basis of transmission of the baroque style (described by Pope Benedict XVI as one of three authentically Catholic liturgical artistic traditions, along with the gothic and the iconographic). The method is named after the art academies of the seventeenth century. The most famous early Academy was opened by the Carracci brothers, Annibali, Agostino, and Ludivico, in Bologna in 1600. Their method became the standard for art education and nearly every great Western artist for the next 300 years received, in essence, an academic training.

Under the influence of the Impressionists the method almost died out. They consciously broke with tradition and refused to pass it on to their pupils. This is strange given that all the well known Impressionists were themselves academically trained, used the skills they learned in their art and in fact could not have produced the paintings they did without it. By 1900 the grand academies of Europe had closed. The fact that it survives at all is largely the legacy of the Boston group of figurative artists of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, most prominent among them John Singer Sargent (who was trained in Paris, but knew them and mixed with them). Other names are Joseph de Camp, Edmund Tarbell and Emil Grundmann. The US was slower to adopt the destructive ideas of Europe and the traditional schools survived there a little longer. Ives Gammell received his training at Boston Museum of Fine Arts in the years just before the First World War. The most well know ateliers that exist today in the US and Italy, were opened by artists who trained under Gammell in the 1970s (when he was in his 80s). Most of people painting and teaching in this style today, that I know of, come out of this line.

Under the influence of the Impressionists the method almost died out. They consciously broke with tradition and refused to pass it on to their pupils. This is strange given that all the well known Impressionists were themselves academically trained, used the skills they learned in their art and in fact could not have produced the paintings they did without it. By 1900 the grand academies of Europe had closed. The fact that it survives at all is largely the legacy of the Boston group of figurative artists of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, most prominent among them John Singer Sargent (who was trained in Paris, but knew them and mixed with them). Other names are Joseph de Camp, Edmund Tarbell and Emil Grundmann. The US was slower to adopt the destructive ideas of Europe and the traditional schools survived there a little longer. Ives Gammell received his training at Boston Museum of Fine Arts in the years just before the First World War. The most well know ateliers that exist today in the US and Italy, were opened by artists who trained under Gammell in the 1970s (when he was in his 80s). Most of people painting and teaching in this style today, that I know of, come out of this line.

The ateliers of the 19th century had become detached from their Christian ethos and the sacred art of the period was inferior to that of the period 200 years before. However, portraiture, and especially that of the Sargent and the Boston School retained the principles of the balance of sharpness and focus, the variation in colour intensity and the contrast in light and dark that characterized the baroque. Today, even portraiture has declined (Wingate and his ilk being exceptions to this) because very often it is based upon photographic images rather than observation from nature. Photographs reflect the distortion of the lens of the camera, which is different from that of the eye; they have too many sharp edges and everywhere is both highly detailed and highly coloured. Consider, for example, how Wingate has handled the drapery in the portrait at the top, left. He has not supplied a fully detailed rendering, yet there is not a sense of a lack of detail because when we look at the figure, which is what Wingate wants us to look at, the detail supplied is sufficient for our peripheral vision.

The ateliers of the 19th century had become detached from their Christian ethos and the sacred art of the period was inferior to that of the period 200 years before. However, portraiture, and especially that of the Sargent and the Boston School retained the principles of the balance of sharpness and focus, the variation in colour intensity and the contrast in light and dark that characterized the baroque. Today, even portraiture has declined (Wingate and his ilk being exceptions to this) because very often it is based upon photographic images rather than observation from nature. Photographs reflect the distortion of the lens of the camera, which is different from that of the eye; they have too many sharp edges and everywhere is both highly detailed and highly coloured. Consider, for example, how Wingate has handled the drapery in the portrait at the top, left. He has not supplied a fully detailed rendering, yet there is not a sense of a lack of detail because when we look at the figure, which is what Wingate wants us to look at, the detail supplied is sufficient for our peripheral vision.

If you go somewhere where you can see a series of portraits painted over long period (perhaps those of the principals hanging in the dining hall of a long-established school or college - I recently went to a dinner at the Roxbury Latin School in Boston - founded in the 17th century), you can see this difference between the traditional and the modern portraits very easily.

those of the principals hanging in the dining hall of a long-established school or college - I recently went to a dinner at the Roxbury Latin School in Boston - founded in the 17th century), you can see this difference between the traditional and the modern portraits very easily.

I am not against photographic portraits by the way, far from it. The point is that it is a different medium to painting, to which we respond differently. These Christian considerations can be communicated through photography, in my opinion, but they have to be done differently. (And if there are any photographers out there, I think that relating the art of photography to the Christian tradition of visual imagery is an area that has not yet been properly developed.) The point here is that paintings made from photographs rarely work unless the artist is conscious of these stylistic considerations and has the skill and experience to adapt what the photographic information.

The retention of these principles in 19th-century portrait painting was not due to a Christian motivation, to my knowledge. If a portrait painter is to make a living then he cannot indulge in the free expression that one might see in other forms. The portrait painter, Christian or not, must seek to balance two things. First, he must produce a painting that is attractive to those who are going to see it, usually the individual and those who know him or her. The usual approach to this is to bring out the best human characteristics of the person. He is ennobling - idealizing - the individual. However, he cannot take this too far and go beyond the bounds of truth. He must also capture the likeness of the individual otherwise it will not be recognized as a portrait. My teacher in Florence, Charles Cecil, taught us not to be bound by an absolute standard of visual accuracy, but to modify what we saw, slightly. We were told to stray ‘towards virtue rather vice’: strengthen the chin slightly, for example. This approach is consistent with the Christian artist’s portrayal of a person, which is as much about revealing what a person can be, as what he is. The idea that the crucial aspect by which the artist reveals the person is by capturing the likeness goes back to St Theodore the Studite, the Church Father whose theology settled the iconoclastic controversy in the 9th century.

For the work of Henry Wingate, see www.henrywingate.com.

Two Hearts Beat as One - An 'Original Copy' of the Sacred Heart of Jesus!

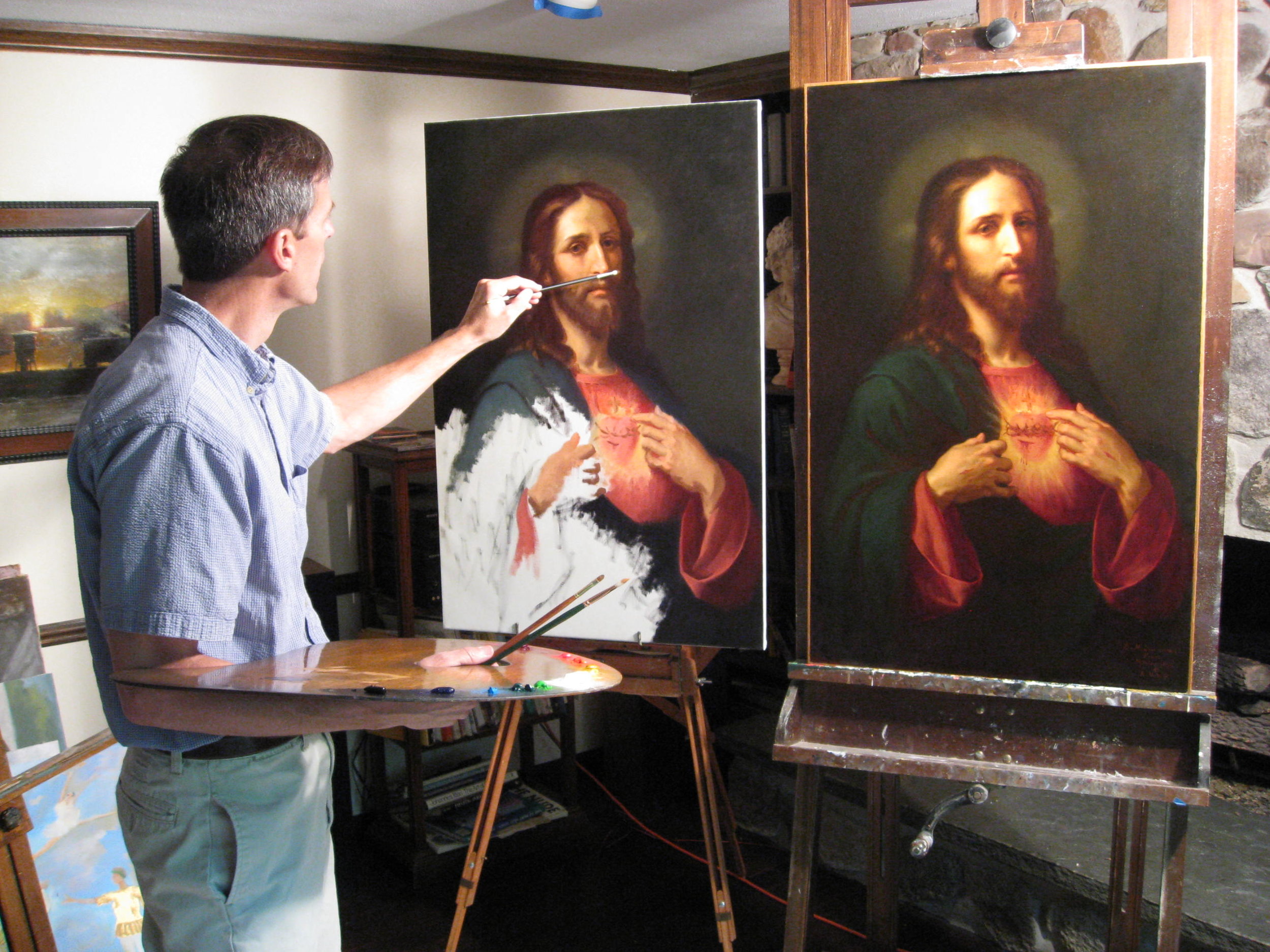

The painting of the Sacred Heart shown is painted by the Virginia-based Catholic artist, Henry Wingate. The process by which it was commissioned and painted is worth recounting as it demonstrates a number of principles.

Last February I was contacted several months ago by John Fitzpatrick, a seminarian at the Kenrick Seminary in St Louis, who has seen me speak there a couple of months before. He wanted to know if I could recommend an artist who produce a painting based upon his favourite image of the Sacred Heart of Jesus by the 19th century Mexican artist Jose Maria Ibarraran y Ponce. I recommended that he contacted Henry and passed on the contact details.

The painting of the Sacred Heart shown is painted by the Virginia-based Catholic artist, Henry Wingate. The process by which it was commissioned and painted is worth recounting as it demonstrates a number of principles.

Last February I was contacted several months ago by John Fitzpatrick, a seminarian at the Kenrick Seminary in St Louis, who has seen me speak there a couple of months before. He wanted to know if I could recommend an artist who produce a painting based upon his favourite image of the Sacred Heart of Jesus by the 19th century Mexican artist Jose Maria Ibarraran y Ponce. I recommended that he contacted Henry and passed on the contact details.

I had forgotten all about this until Henry arrived to teach at the summer Way of Beauty Atelier at Thomas More College in New Hampshire, this summer. He had with him the finished piece of work., which was put on show at the college for the duration of the class.

He told me about how it had worked: he wanted to do the commission but was adamant that if at all possible he wanted to work from the original. After a bit of research he found out that the original was owned by David Pappas, a collector who lives in Minnesota. He loves the image and was very happy to make it available for copying. So Henry flew out to Minnesota and copied it there. I show some photographs of the work in progress, next to the original.

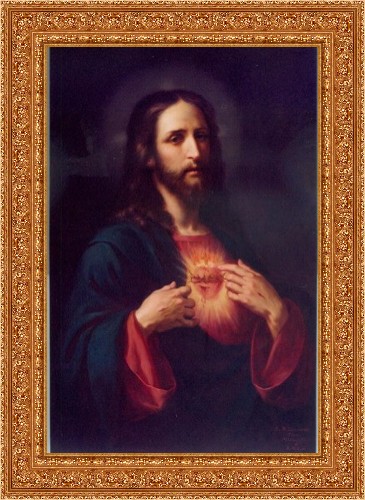

I spoke to Mr Pappas who was delighted to have met Henry and to have been helpful in the project. He told me that he enjoyed meeting Henry very much. He told me a little bit about the original. As far as he knows this is the only extant work or the artist, who was the director of Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Mexico City around the turn of the last century. It was commissioned by members of the Miller brewing family, who were Catholics and devoted to the Sacred Heart and completed in 1896.

In my opinion it is a wonderful painting (the original is shown right). Although from the 19th century, it has a 17th century feel. The restraint in the use of colour and his careful control of focus is typical of the earlier period (as many NLM readers will have heard me describe before). Also, he has played down the features of the face by putting them partially in shadow. This way he has avoided that look of a portrait of the boy next door in historical costume (which we see in so much 19th-century and modern naturalistic sacred art).

In my opinion it is a wonderful painting (the original is shown right). Although from the 19th century, it has a 17th century feel. The restraint in the use of colour and his careful control of focus is typical of the earlier period (as many NLM readers will have heard me describe before). Also, he has played down the features of the face by putting them partially in shadow. This way he has avoided that look of a portrait of the boy next door in historical costume (which we see in so much 19th-century and modern naturalistic sacred art).

This process emphasizes the importance of copying the works of Masters in the preservation and transmission of any tradition. Traditionally, the training of artists always included the copying (with understanding) of the works of Masters – Sargent for example, went to Madrid and copied every Velazquez he could see. This is not to devalue the end product. Just as the copying of icons allows for the creation of a new icon worthy of veneration, so Henry has created an work of art, itself worthy of veneration (once the name is placed on it, of course, in accordance with the theology of Theodore the Studite).

John Fitpatrick was delighted with the result: “I am very happy with the finished painting. I was interested in this project for reasons: I have a personal devotion to the Sacred Heart and this is my favourite image. Ideally, the painting will hang somewhere in my living quarters when all's said and done, maybe even adorning an altar.

“I'm also very glad to hear you're doing a piece on the commissioning process.” He told me. “I think clerics today--as well as laymen--don't realize that direct commissioning of an artist to create worthy art for sacred use is even possible and so it is good for this to be made known. I also think it's important to remember that it is through the commissioning of artists that all the great works of sacred art came about, but that they were not cheap; when commissioning artists, we have to be ready to bleed a little bit for the product.”

High quality reproductions of the original are available from David Pappas at his gallery Strawberry Hill Ltd. Also, the original is for sale. Thomas More College of Liberal Arts is dedicated to the Sacred of Jesus and so if any readers feel inclined to buy it and donate it to the college, we would be happy to entertain approaches!

Cosmic Onions? What does a Still Life Have to Do with the Liturgy

It is said that all the great art movements begin on the altar. So, for example, the gothic style began as the style for gothic churches and cathedrals in harmony with the liturgy. However, very quickly the architecture of mundane buildings of the period reflected that form too, adapted as appropriate to the purpose of the building (the colleges of Oxford and Cambridge immediately come to mind). Similarly, the baroque style of art and architecture, which began as liturgical forms, became the model for all building and art of the period, with for example, the portraits and landscapes of the 17thcentury reflecting the stylistic forms of the liturgical art of Ribera, Velazquez and Rubens.

This is not just an arbitrary extension of style into non religious subjects. It is consistent with the idea that the whole of the cosmos reflects and points to the rhythms and patterns of the heavenly liturgy. So any art form that is in harmony with the liturgy, will also be harmony with the cosmos. The cosmos, in the context of this discussion, is the mundane. I repeat a remark made to me recently (and no doubt will do so in the future, for it says it so well): the Mass is a jewel in its setting, which is the Liturgy of the Hours; and in turn the liturgy as a whole is itself a jewel in its setting, which is the cosmos. When we perceive God's creation as a thing of wonder and beauty, we are recognizing at a deeply intuitive level, the harmonious relationships between all aspects of the cosmos and the heavenly order. The heavens point to Heaven and circle is completed.

It is said that all the great art movements begin on the altar. So, for example, the gothic style began as the style for gothic churches and cathedrals in harmony with the liturgy. However, very quickly the architecture of mundane buildings of the period reflected that form too, adapted as appropriate to the purpose of the building (the colleges of Oxford and Cambridge immediately come to mind). Similarly, the baroque style of art and architecture, which began as liturgical forms, became the model for all building and art of the period, with for example, the portraits and landscapes of the 17thcentury reflecting the stylistic forms of the liturgical art of Ribera, Velazquez and Rubens.

This is not just an arbitrary extension of style into non religious subjects. It is consistent with the idea that the whole of the cosmos reflects and points to the rhythms and patterns of the heavenly liturgy. So any art form that is in harmony with the liturgy, will also be harmony with the cosmos. The cosmos, in the context of this discussion, is the mundane. I repeat a remark made to me recently (and no doubt will do so in the future, for it says it so well): the Mass is a jewel in its setting, which is the Liturgy of the Hours; and in turn the liturgy as a whole is itself a jewel in its setting, which is the cosmos. When we perceive God's creation as a thing of wonder and beauty, we are recognizing at a deeply intuitive level, the harmonious relationships between all aspects of the cosmos and the heavenly order. The heavens point to Heaven and circle is completed.

The work of man, through God's grace can, simply through its beauty, participate in this cosmic order and therefore direct the souls of mankind to the heavenly order too, believer and non-believer alike. It is through the mundane aspects of Catholic culture that we look to therefore, to lay the groundwork, so to speak, of drawing the non-believers to God, for it will be very likely the first aspect of Catholic culture that they will have contact with. A beautiful landscape or still life can open up the souls so that they might become fertile ground for the later sowing of the seed of the word.

The work of man, through God's grace can, simply through its beauty, participate in this cosmic order and therefore direct the souls of mankind to the heavenly order too, believer and non-believer alike. It is through the mundane aspects of Catholic culture that we look to therefore, to lay the groundwork, so to speak, of drawing the non-believers to God, for it will be very likely the first aspect of Catholic culture that they will have contact with. A beautiful landscape or still life can open up the souls so that they might become fertile ground for the later sowing of the seed of the word.

The baroque painting of the 17th century, is a naturalistic form that is every bit as integrated with the Catholic worldview as the iconographic. The baroque portrays our naturalistic world as imperfect, fallen, but nevertheless still good. It's aim is to acknowledge the presence of evil and suffering, while offering hope through Christ that transcends it. Much of the visual vocabulary of the tradition is linked to contrast of despair and the hope that transcends it for example in the symbolism of light contrasted with darkness; of variation of focus in which those areas of primary interest are sharper and crisper than those of secondary interest; and of variation in colour in which those areas of primary interest are rendered in naturalistic colour, while those of secondary interest are rendered tonally in monochrome. In the context of sacred art, I have written about it, for example here.

A simple still life, therefore, can portray the work of God or man (inspired by God) and it does so by employing the same visual tools. Whereas a landscape looks at the broad horizon in wonder, the still life invites contemplation of the small and ordinary aspects of everyday life. through them we can see how even these small otherwise unremarkable details of the day conform to and participate in the same liturgical dynamic as the grand cosmos. The Christian artist can create cosmic vegetables, or cosmic pots and pans that, in the words of the Canticle of Daniel, ‘give praise to Lord’.

The model to look to in this regard is the French 18th century artist, Jean Baptiste Simeon Chardin. His is the painting shown above. The person who drew my attention to Chardin is Henry Wingate, a Catholic and Virginia-based artist who is a wonderful painter of portraits and still lives. (He is also a gifted teacher who his teaching the naturalistic drawing class at the Thomas More College summer program this year.)

I show below an example of a still life by Wingate which reflects, in my opinion, the baroque vision of the world. I you wish to see more I posted a series of his still lives recently, here; and for those who are interested, I have written about his portraits here.

Above: still life by Henry Wingate; below: Jar of Olives and Silver Cup, by Chardin (1699 - 1779)

The Still Lives of Henry Wingate - teacher at the TMC Summer Program

Henry Wingate is an internationally known artist in the Western naturalistic tradition. Based in Virginia, he excels particularly at portraits (he is has a waiting list of commissions) and still lives. I have written in the past about how his portraits reflect the baroque form. Here are some examples of his still lives. Henry is also a a gifted teacher who will once again direct students in the naturalistic drawing class this summer at the Thomas More College's Way of Beauty Atelier this summer.

The two-week drawing course will not only teach the traditional academic method (which has its roots in the methods developed by Leonardo Da Vinci) but will supported by regular talks by myself and Henry about the tradition, which is a form fully integrated with the Catholic worldview as well as traditional compositional design and proportion.

Henry Wingate is an internationally known artist in the Western naturalistic tradition. Based in Virginia, he excels particularly at portraits (he is has a waiting list of commissions) and still lives. I have written in the past about how his portraits reflect the baroque form. Here are some examples of his still lives. Henry is also a a gifted teacher who will once again direct students in the naturalistic drawing class this summer at the Thomas More College's Way of Beauty Atelier this summer.

The two-week drawing course will not only teach the traditional academic method (which has its roots in the methods developed by Leonardo Da Vinci) but will supported by regular talks by myself and Henry about the tradition, which is a form fully integrated with the Catholic worldview as well as traditional compositional design and proportion.