The new Stabat Mater Studio in Tyler, Texas, is dedicated to training the next generation of liturgical artists in an authentically Catholic environment and offers the five core disciplines of any traditional Catholic artistic training.

The Beauty of God's House - a Collection of Essays Published as a Tribute to Stratford Caldecott

Readers might be interested to know of newly published book, the Beauty of God's House, which is a Festschrift for Stratford Caldecott. It is a collection of essays edited by Prof Francesca Murphy and features contributions from the Davids Schindler, Marc Ouellet, John Milbank, Aidan Nichols, Adrian Walker, Jean Borella, David Fagerburg, Nick Healy Jr, Michael Cameron, Phil Zaleski, Carol Zaleski, Derek Cross, Mary Taylor, Reza Shah-Kazemi, and myself with an afterword by his wife Leonie Caldecott.

The book covers the whole range of Caldecott's interests, from poetics to politics. Anyone interested in the field of theology and the arts will find much to intrigue them. If there is a common thread that runs through them all it is, as the title suggests, Stratford's interests is in the beauty of the cosmos and how it reflects the beauty of God.

Readers might be interested to know of newly published book, the Beauty of God's House, which is a Festschrift for Stratford Caldecott. It is a collection of essays edited by Prof Francesca Murphy and features contributions from the Davids Schindler, Marc Ouellet, John Milbank, Aidan Nichols, Adrian Walker, Jean Borella, David Fagerburg, Nick Healy Jr, Michael Cameron, Phil Zaleski, Carol Zaleski, Derek Cross, Mary Taylor, Reza Shah-Kazemi, and myself with an afterword by his wife Leonie Caldecott.

The book covers the whole range of Caldecott's interests, from poetics to politics. Anyone interested in the field of theology and the arts will find much to intrigue them. If there is a common thread that runs through them all it is, as the title suggests, Stratford's interests is in the beauty of the cosmos and how it reflects the beauty of God.

I contributed an essay on the place of the nude in Christian art in the light of JP II's Theology of the Body (and other writings including his address at the opening of the newly restored frescoes of the Sistine Chapel and his Letter to Artists). The common lore has him as a Catholic apologist for the Sixties who stripped the loin cloths and fig leaves from the Sistine Chapel. In fact he spoke very strongly against naturalistic representations of the nude and I argue that in fact he was as about as conservative in his approach to the pictorial representation of nudity as Pius IV (who had some fig leaves painted on the Sistine Chapel some years after it was first painted).

I don't explain in the essay, but the reason I wrote this arises directly from conversation with Strat and Leonie Caldecott some years ago. I was working with both at the time to organise a summer drawing school in Oxford teaching the academic method and we were looking for a model for a life drawing class that was to be included. We couldn't find one and in the end someone we all knew well volunteered, but she would not disrobe. None of us wanted her too either because we knew her and that alone made it seem inappropriate. So what we did in the end was ask her to model, elegantly dressed, for what we called a full-figure portraiture class. Realising that if I was going to establish an art school for Catholics I was going to have to address this issue head-on I decide to do some research.

At that time I had unquestioningly accepted the received wisdom that came from Catholics and non-Catholics alike that it was part of the tradition and necessary for any good training of an artist. Therefore, I was looking to find justifications for the nude and for figure drawing as a practice that I could use against what I perceived to be over puritanical Catholics. I immediately headed for JPII believing he would be my great ally here, as well as various other authors. Strat suggested to me that I read an article that had been printed in Communio some years earlier. It was a reprint of a piece written by a contemporary and friend of Jacques Maritain called Erik Petersen and was entitled A Theology of Dress. Here was the complementary theology to the Theology of the Body and I found that the two were founded on complete harmony of thought. As I studied these writings and the Catholic tradition of figure painting, to my surprise I came to the opposite conclusion. I felt that the place of the nude in the Catholic tradition had been greatly exaggerated latterly and also that nude figure drawing is not necessary for the training of artists. The article explains my thinking in detail.

I intend to post a review of the book when I have read the contributions of the other authors.

It is available from the publisher, Cascade Books, here.

Why All Christian Artists Must Learn to Draw - And Where You Can Learn To Do It Well

Summer Drawing Classes in the Academic Method at the Ingbretson Studios, Manchester NH

All figurative Christian art, and especially sacred art, is a balance between natural appearances and idealisation. Idealisation is the controlled distortion from natural appearances that enables the artist to communicate invisible truths.

Summer Drawing Classes in the Academic Method at the Ingbretson Studios, Manchester NH

All figurative Christian art, and especially sacred art, is a balance between natural appearances and idealisation. Idealisation is the controlled distortion from natural appearances that enables the artist to communicate invisible truths.

Some people assume that working in a style such as the gothic or iconographic is easier than in more naturalistic styles, but in fact to be able to work in a style well is takes great skill. The artist must be aware of span the divide between the two worlds he is representing. If there is too great an emphasis on natural appearances, then it lacks mystery. If the distortion so too great, then we lose a sense of the material. Artists should be aware too, that in sacred art the degree of naturalism should be less than in mundane art - for example landscapes and portraits.

Pius XII spoke of this in Mediator Dei (195) he refers to this balance (he uses the word 'realism' for my naturalism; and 'symbolism' for my idealism): 'Modern art should be given free scope in the due and reverent service of the church and the sacred rites, provided that they preserve a correct balance between styles tending neither to extreme realism nor to excessive "symbolism," and that the needs of the Christian community are taken into consideration rather than the particular taste or talent of the individual artist.'

The first step in getting this right is studying the tradition to develop a sense of where the balance lies. Even so, different artists will have a different sense of exactly where this balance lies, but even recognition of the fact that there can be excessive naturalism and excessive abstraction and that he should seek the temperate mean goes a long way to getting it right.

The second step is getting the skill to represent precisely both the naturalistic and the idealistic (by reflecting accurately the idea of the mind in the artist). The artist who cannot draw well from nature cannot do this, for no matter how well conceived his ideas may be he cannot represent them accurately if he cannot draw well. Therefore learning to draw well is an essential part of the training of any artist. Regardless of the style in which he ultimately intends to paint in, I would recommend everyone to learn to draw rigorously. The best drawing training that I know is the academic method. I spent a year learning this in the Florence atelier of Charles H Cecil with the blessing of my icon painting teacher even though the style is very different. As a result the quality of my icon painting went up by orders of magnitude. A danger of learning the academic technique is that of being so dazzled by how ones drawing improves that one forgets that technique is only the means to an end and not the end. The artist must realise that he cannot succeed on technique alone and so should not neglect the development of his understanding tradition and how to direct those skills in the service of God.

Those who wish to learn this technique can come along to the Thomas More College summer school art program. This is done in conjunction with the world reknowned Ingbretson Studio, featured here:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fbtBW2T50p0 In this class a day spent in the studio is supplemented by a series of lectures explaining the basis of the tradition and placing the use of it within the context of Catholic sacred art so that you always control the technique in the service of the Church.

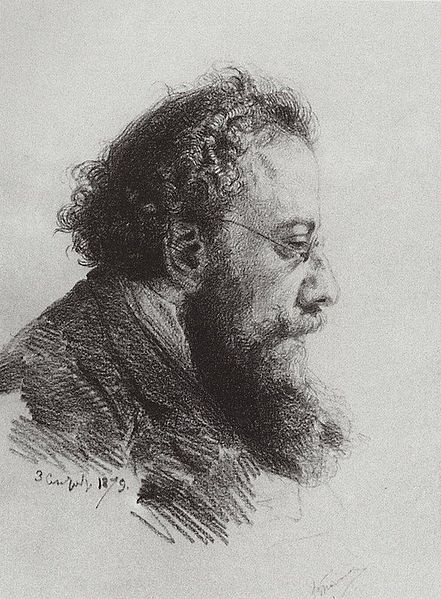

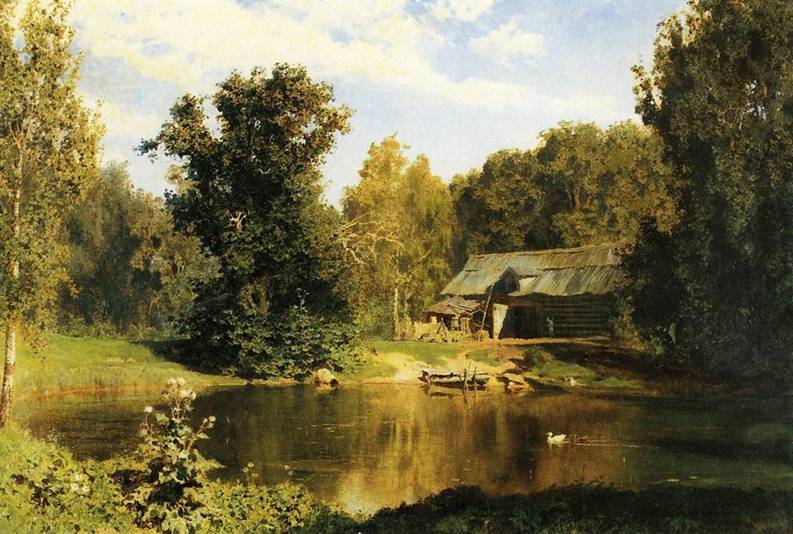

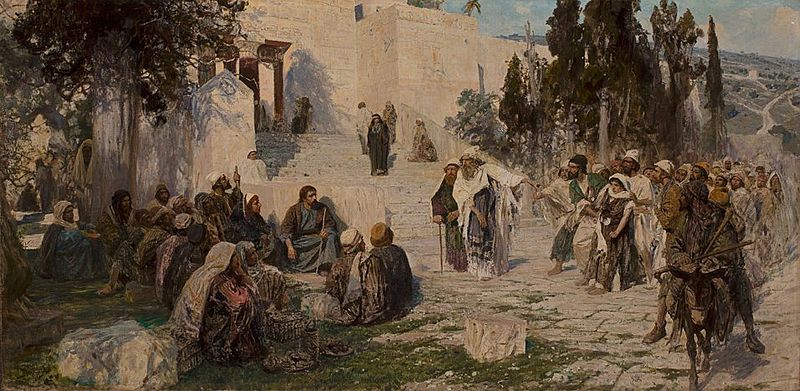

Just to illustrate the level of drawing skill achieved by the academic method. Here is work from the Russian 19th century Master Vasiliy Polenov. He is highly skilled. You can see a couple of examples of his drawings including one of a bibilical scene - the raising of the daughter of Jairus. I have also included a couple of his landscapes.

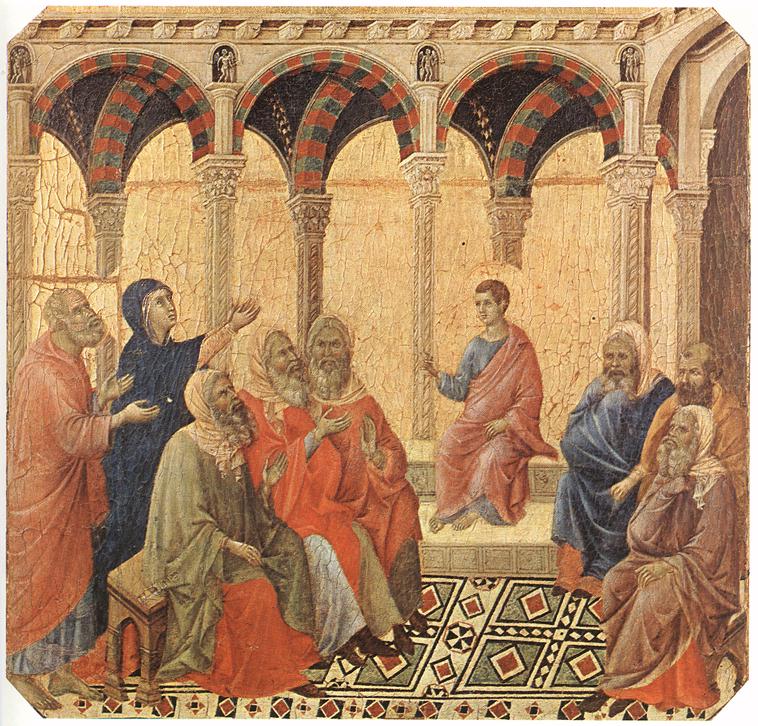

In my personal judgement, he was a superb draughtsman and has dazzling technical skill. This works wonderfully in the landscapes. However, it is not sufficiently abstracted or symbolic for sacred art and so his bibilical scenes look more like what we used to seeing as color plates in children's bibles than devotional art. It is interesting to note that in Russia in the 19th century, this is how art for churches was painted and part of process of reestablishing the Russian iconographic tradition, which happened in the 20th century as reaction to this by figures at the turn of the last century such as Fr Pavel Florensky. His analysis was then picked up by painters such as Ouspensky and Kroug in the mid-20th century.

The purpose of this not to argue against the validity of the academic training. In fact it is the opposite, I would argue that it has great value; but if one is to use it in the services of sacred art, one must be aware of how to direct that skill towards the right balance of naturalism and idealism. This is the special element, expressed in an explicitly Catholic way, is included in the classes I have described above, and which is absent from nearly all others.

Below: first, the raising of Jairus' daughter in full, then a drawing - portrait of an art critic; a superb landscape of a Russian rural scene; then two bibilical scenes - 'he who is without sin' and the boy Jesus found in the temple teaching the teachers. By way of contrast I show Duccio's version of the same subject that has a much more abstracted style.

And here is a poster for the summer drawing class run by TMC and the Ingbretson Studios

Thomas More College links up with Internationally Known Atelier, Ingbretson Studios, Again

Thomas More College of Liberal Arts is pleased to announce that once again that undergraduates, the college's Guild of St Luke will be able to attend a weekly, day-long course in academic drawing at Ingbretson Studio, the internationally known studio of Paul Ingbretson in Manchester, New Hampshire. This is ideal for those want to go to college and get a Catholic formation, but don’t want to leave their art behind while they study. Thomas More College of Liberal Arts continues to be the one place where you can study both.

This was a course run for the first time last semester and it was so successful that we are giving up to a dozen undergraduates the chance to learn this traditional method again. Through this they will receive a training that will give them a level of skill in drawing that is greater than many leaving a conventional art school after four years' study. The photographs shown are of the drawings produced by last year's students.

Thomas More College of Liberal Arts is pleased to announce that once again that undergraduates, the college's Guild of St Luke will be able to attend a weekly, day-long course in academic drawing at Ingbretson Studio, the internationally known studio of Paul Ingbretson in Manchester, New Hampshire. This is ideal for those want to go to college and get a Catholic formation, but don’t want to leave their art behind while they study. Thomas More College of Liberal Arts continues to be the one place where you can study both.

This was a course run for the first time last semester and it was so successful that we are giving up to a dozen undergraduates the chance to learn this traditional method again. Through this they will receive a training that will give them a level of skill in drawing that is greater than many leaving a conventional art school after four years' study. The photographs shown are of the drawings produced by last year's students.

Paul Ingbretson is a modern Master of the Boston school and is one of those I mentioned who was given his training by Ives Gammell in the 1970s. He has been teaching ever since. His school has an international reputation (we were all well aware of it, for example, when we were studying in Florence). He teaches the rigorous 'academic method' of drawing which can be traced back to the methods of Leonardo da Vinci and was used by figures such as Velazquez and more recently, John Singer Sargent.

By coincidence Ingbretson Studios is just 10 minutes drive from the TMC campus. Those who have a strong enough interest will also have an opportunity to train full time for three solid months each summer if they wish to do so. This is part of the college art guild of St Luke in which students are able to learn also traditional iconography and sacred geometry.

I teach a course to all freshmen who attend the college called The Way of Beauty in which students learn in depth about Catholic culture, especially art and architecture, and its connection to the liturgy.