A composer tells us his approach in composing works that are fresh and new, while reflecting the timeless principles that constitute sacred music. Listen also to his beautiful newly composed Mass.

The following is an essay written by the composer Paul Jernberg. Paul has composed his Mass of St Philip Neri for the new translation of the Mass. In the essay below he discusses the principles that guide him in composition and which enable him to compose new music in accordance with timeless principles. We have been singing his compositions at Thomas More College - I have been working with him in creating psalm tones for the vernacular that are modal and so sit within the tradition.This has enabled us to chant, for example, the traditional Latin proper for communion and then a communion meditation in English without any sense of disunity.

A composer tells us his approach in composing works that are fresh and new, while reflecting the timeless principles that constitute sacred music. Listen also to his beautiful newly composed Mass.

The following is an essay written by the composer Paul Jernberg. Paul has composed his Mass of St Philip Neri for the new translation of the Mass. In the essay below he discusses the principles that guide him in composition and which enable him to compose new music in accordance with timeless principles. We have been singing his compositions at Thomas More College - I have been working with him in creating psalm tones for the vernacular that are modal and so sit within the tradition.This has enabled us to chant, for example, the traditional Latin proper for communion and then a communion meditation in English without any sense of disunity.

What characterises both the compositions you can hear here and the music he has composed for us at Thomas More College of Liberal Arts is how simple it is to perform, yet how good it sounds. He really has hit that standard of noble simplicity - music that is so beautiful that you want to sing it, and so simple that you can. Furthermore, there is not even a hint of sentimentality in his music.

I have punctuated the text of his essay with links through to audio of the St Philip Neri Mass so that you can pause and listen as you read along. The attached audio files have been recorded by members of the Parish Choir of St. John's in Clinton, MA and of the Chorus of Trivium School, a Catholic high-school in Lancaster, MA (plus myself and Dr Tom Larson from Thomas More College of Liberal Arts and an additional member of Tom's amateur chant and polyphony choir, the Schuler Singers). Please bear in mind as you listen to them that they are not professional recordings and precisely because it is amateur singers that you are listening to it represents an endeavor to incarnate the ideal articulated in the essay on the Parish level:

The Logos of Sacred Music

An introduction to the Mass of Saint Philip Neri

The composition of this work has been my response to the need for a fitting musical setting of the Ordinary from the new English translation of the Roman Missal. In the creation of this music it has been my goal to fulfill three essential criteria, namely, that it have a true sacred character, that it be imbued with the qualities of authentic artistry, and that it possess a noble accessibility will allow it to be received into the hearts of ordinary people of good will throughout the English-speaking world.

Sacred Character

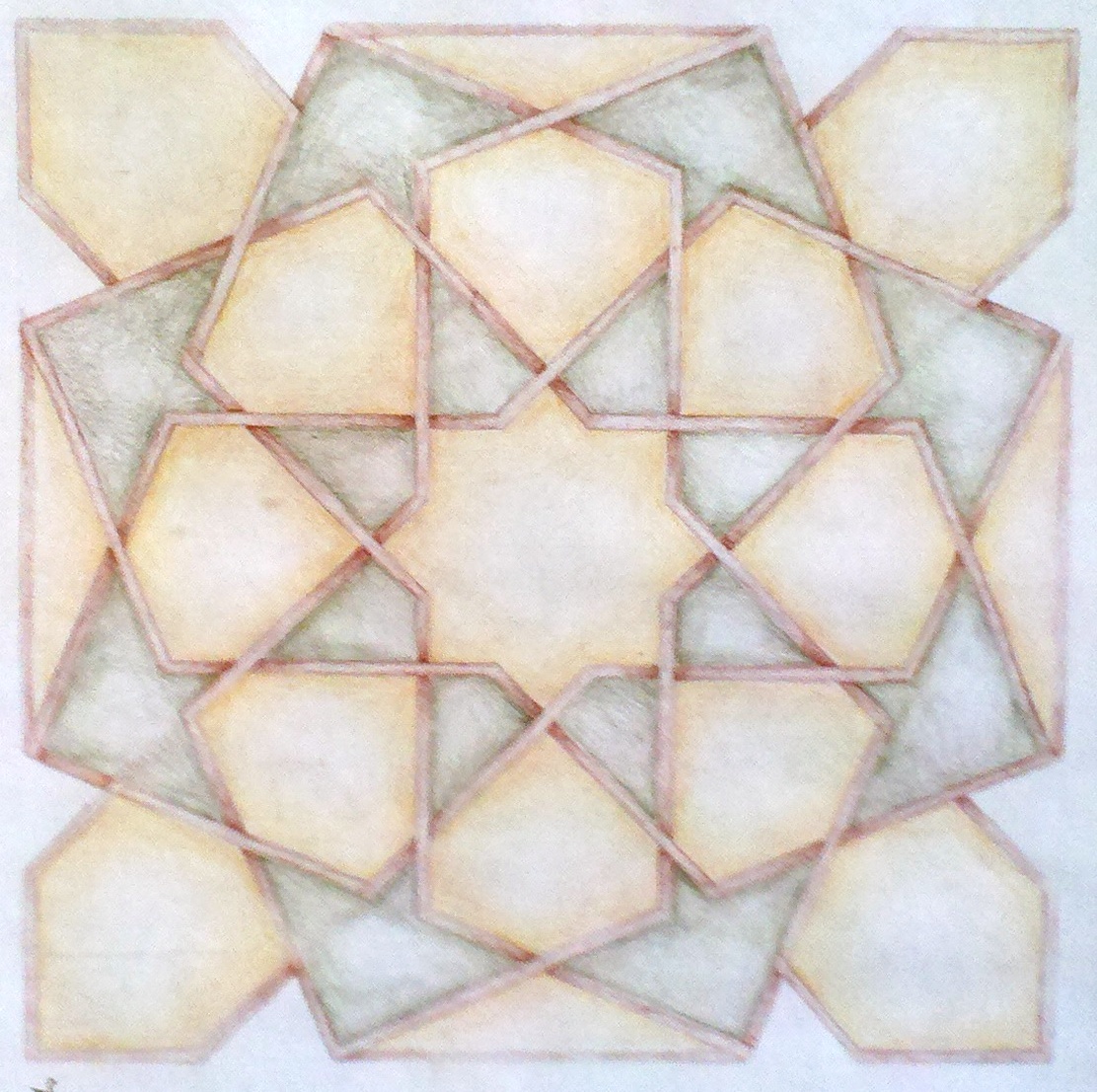

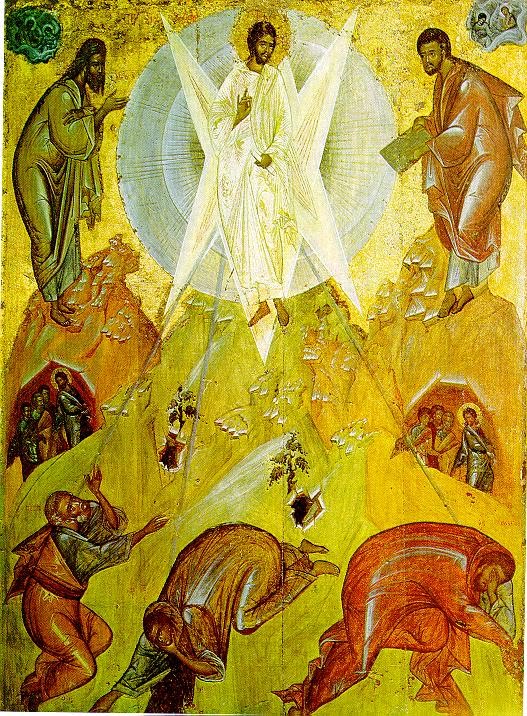

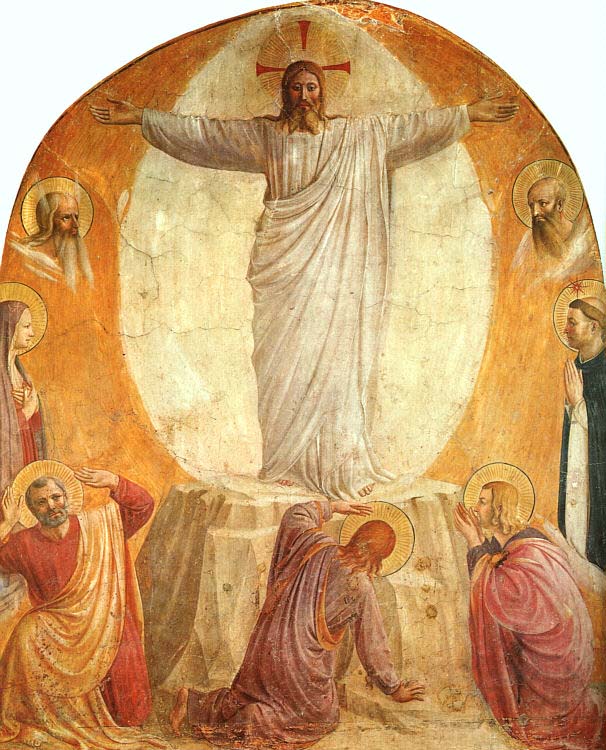

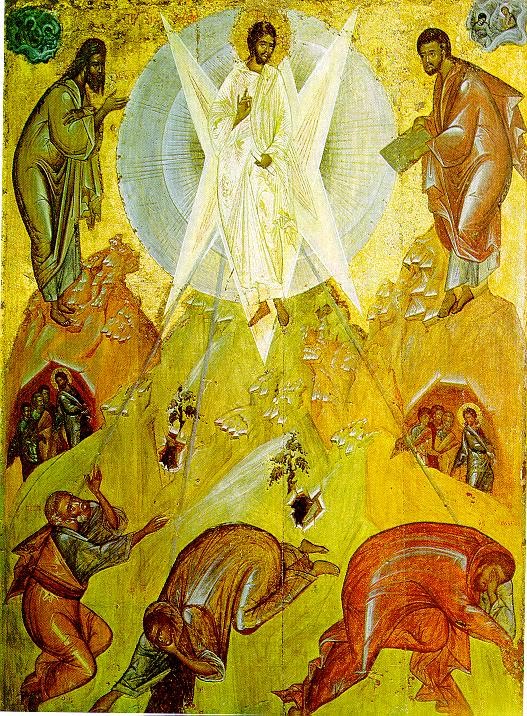

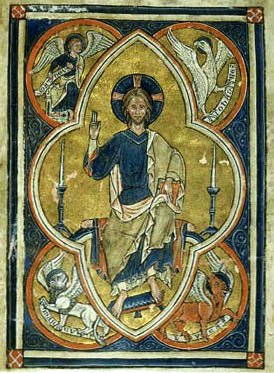

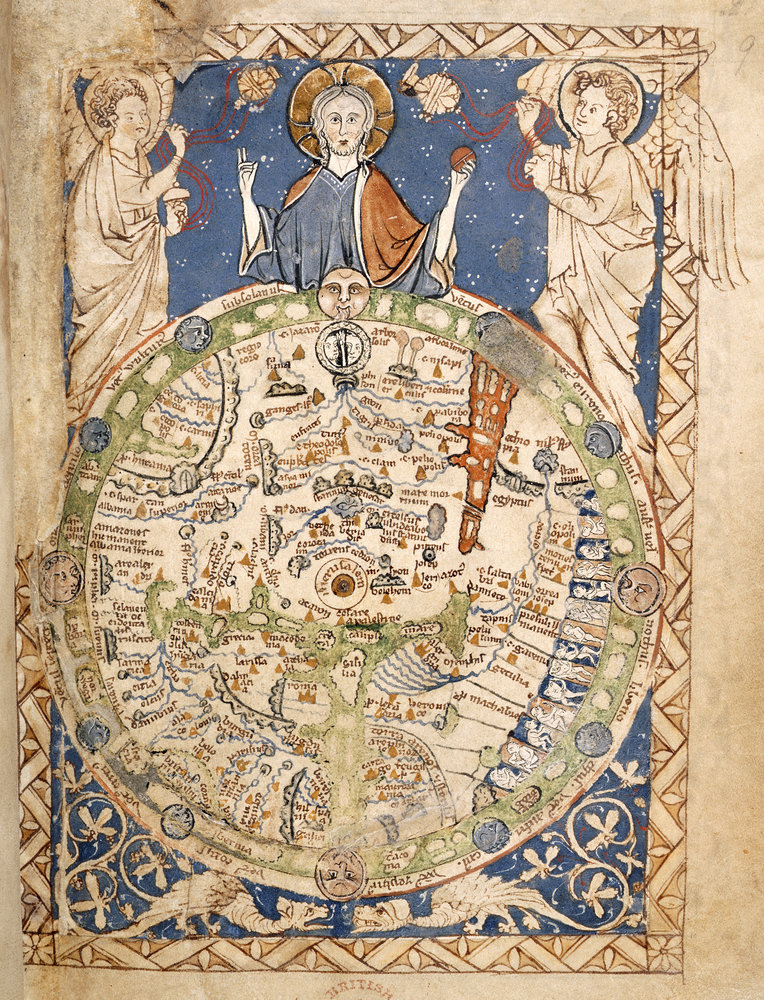

Music in the Liturgy of the Catholic Church should by its nature have a distinct identity that is contemplative, vibrant, and rooted in ancient tradition. In the perennial Catholic vision of the Liturgy, all of its sensible elements are intended to provide a sacred space that is worthy to welcome the sacramental Divine Presence. This intention would seem to surpass the reasonable scope of ordinary human creativity, as the finite aspires to welcome the infinite, the creature to create a worthy space for the Creator. And yet, both faith and aesthetic sensitivity perceive that an inspired tradition has indeed developed over the course of the centuries – including aspects such as architecture, visual arts, and music - which has fulfilled this task in a marvelous way.

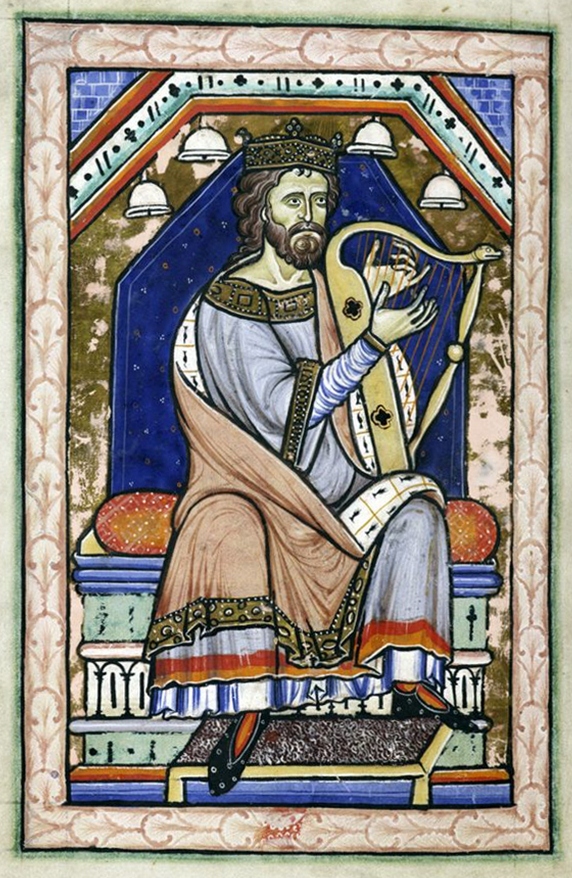

In the West, this inspired musical tradition has as its foundation a vast repertoire commonly known as Gregorian Chant. Any composer who wishes to approach the task of composing music for the Roman Catholic Liturgy in a serious way, should thus be thoroughly versed in the study and performance of this repertoire, realizing the littleness of his own efforts in relation to the greatness of the tradition. The composer should also seek to understand and apply those musical principles of Gregorian Chant that have allowed it to serve its purpose so aptly. As expressed by the authors of the post-conciliar Church document, Musicam Sacram:

Musicians will enter on this new work with the desire to continue that tradition which has furnished the Church, in her divine worship, with a truly abundant heritage. Let them examine the works of the past, their types and characteristics, … so that “new forms may in some way grow organically from forms that already exist,” and the new work will form a new part in the musical heritage of the Church, not unworthy of its past.[1]

And furthermore:

Let them produce compositions which have the qualities proper to genuine sacred music, not confining themselves to works which can be sung only by large choirs, but providing also for the needs of small choirs and for the active participation of the entire assembly of the faithful.[2]

Along these same lines Pope Benedict XVI recently pointed out:

It is possible to modernize holy music, but this cannot happen outside the great traditional path of the past, of Gregorian chants and sacred polyphonic choral music… [3]

What are the “qualities proper to genuine sacred music” that need to be followed attentively in the composition and performance of new works? This is in fact a crucial question which requires much more space than the scope of this introduction would allow, in order to be answered adequately. However, a few first principles can be briefly articulated here:

- The human voice is always the primary instrument, and often the only instrument. Being an integral part of man, rather than his exterior creation, the voice has a unique capacity for intimate expression of the depth and breadth of human feeling and experience. It is equally accessible to all people and all cultures. When the organ or other instruments are used, it is for the purpose of supporting or enhancing, rather than dominating or supplanting, the voice.

- The rhythm of the music is united with the natural rhythm of the given sacred text, either through assuming the textual rhythm as its own, or by engaging in a gentle interplay with it. Any strong metrical or rhythmic effects that might overshadow the meaning of the text are avoided. With a few exceptions, Gregorian chant is characterized by a non-metered rhythm that allows great freedom in respecting the meaning and flow of the Word.

- Melodic lines and harmonies are carefully chosen to evoke dispositions and emotions that are appropriate to liturgical worship and interiority, and which steer clear of secular associations. This distinction is not meant in any way to demean the multifarious beauty that belongs to secular life and art, or to deny its transcendent dimension, but rather is meant to facilitate the flourishing of each - the sacred and the profane[4], divine worship and social intercourse - in its own proper time and place.

Authentic Artistry

It does not do justice to the nature of the Liturgy for its music to be merely correct, even according to the above-mentioned principles. In order for sacred music to reach its full stature, composers and musicians need to exercise true artistry, in which knowledge, inspiration, and skill all play a vital role.

Many may object here, saying that liturgical music is meant for “prayer rather than performance,” implying that prayer, being a humble, intimate communication with God, excludes or minimizes the need for artistry, which by its nature demands a focus on the externals of music-making. There is an element of truth in this, namely, that the relational dimension of the Liturgy is of immeasurably more importance than the artistic dimension. However, it is this very relational dimension which should motivate and empower composers and musicians as they devote all of their skill to create something as beautiful as possible for God, the Beloved. In addition, a certain level of artistry in composition and choral performance provides a foundation from which the other participants in the Liturgy can more fully interiorize the meaning of the words and more prayerfully join in the singing of their parts.

In the context of sacred music, compositional artistry will be manifested in gracefulness and dignity of melodic line, harmony, and dynamics, rather than in striking effects or grandiosity. The artistic performance of this music by cantors and choirs requires, among other things, diligent attention to precision of pitch and rhythm, natural resonance, lively and sensitive dynamics, appropriate tone quality, and clear diction. Qualities such as interiority and unity of sound among voices should preclude any harsh effects or displays of virtuosity, however appropriate these latter might be in other contexts.

Composers and performers of all kinds of music bear witness to the fact that the phenomenon of inspiration is a mysterious but important element in their creative process. How much more should the composer of sacred music, conscious of the dignity of the Liturgy, prayerfully seek that inspiration which will give his music a living, joyful, peaceful identity, beyond the mere notes on the musical score? When this gift is skillfully cultivated, choirs and congregations can in their turn participate in an experience of inspired beauty, which is directed toward the praise and glory of God.

Noble Accessibility

One of the clearest messages from the Second Vatican Council to composers of sacred music, was the need to create music that would facilitate the “full, conscious, and active” participation of the faithful:

In the restoration and promotion of the sacred liturgy, this full and active participation by all the people is the aim to be considered before all else, for it is the primary and indispensable source from which the faithful are to derive the true Christian spirit…[5]

How can music help to achieve this goal, while faithfully maintaining the other foundational qualities listed above? On the one hand, unceasing and genial efforts should be made to help priests and lay people to re-discover the great traditions of sacred music that are in fact their rightful patrimony. Too often this heritage has been ignored or rejected on the false premise that it is no longer relevant to modern man. On the other hand, the legitimate development of culture, as well as the authorized use of the vernacular in the Liturgy, beg for the conception of worthy new music to accompany both Latin and translated Liturgical texts. And in order for this music to fulfill its purpose, it needs to be imbued with a noble accessibility that allows it to be not only admired, but also deeply welcomed by “ordinary” people so as to become a fitting and authentic expression of their faith.

When this quest for full participation has been separated from the need for true sacred character and authentic artistry in liturgical music, as has often been the case over the decades since Vatican II, the results have been deeply disturbing for those sensitive to the musical, psychological and spiritual dimensions of the Mass. As world-renowned maestro Riccardo Muti recently observed:

The history of great music was determined by what the Church did. When I go to church and I hear four strums of a guitar or choruses of senseless, insipid words, I think it's an insult… I can't work out how come once upon a time there were Mozart and Bach and now we have little sing-songs. This is a lack of respect for people's intelligence. [6]

This interview, in which Muti praised the efforts of Pope Benedict to promote a renewal of sacred music, was a tremendous encouragement to me in my composition of the Mass of St. Philip Neri. He speaks authoritatively on behalf of all great musicians and all devout Catholics when he pleads for the renewal of sacred music in the Church’s Liturgy. At the same time he understands the need for accessibility:

Rather than obsess over creating masterpieces, contemporary composers should “prepare the future for a new language in the world of music - not one but several languages - that are more closely connected to the needs of people.” [7]

In searching for compositional models that do integrate sacred character, authentic artistry, and noble accessibility, I have in fact found two wonderful sources of inspiration. The first is the harmonized liturgical chant of the Russian Orthodox Church, developed by composers such as Smolensky, Chesnokov, and Rachmaninoff. The second is the music of Jacques Berthier written for the ecumenical Taizé Community in France, which has brought an elegant simplicity and power to the singing of sacred texts by very large groups of people. In each of these cases, composers with highly sophisticated skills have deliberately set aside the kind of harmonic and rhythmic complexity appropriate to the concert hall, in order to bring intense depth and beauty to simpler forms that thus become nobly accessible to “common” people from a wide variety of backgrounds. Both of these sources have been my constant companions in the composition of this musical setting of the Mass.

St. Philip Neri

I have chosen to name this work in honor of Philip Neri, because his life and apostolate, which effected such a great spiritual and cultural renewal in 16th century Rome, have also been an ongoing inspiration to me and the choirs that I have had the privilege of directing. Through his Oratory movement, which combined prayer, study, works of mercy, joyful fellowship, and the cultivation of the arts, he became a patron to great composers such as Palestrina and Animuccia. Influenced by the contagious holiness and joy of St. Philip, they were able to create a magnificent new repertoire of sacred polyphony, rooted in the ancient tradition of Gregorian chant, but also responding to the new needs and inspirations of their day. My hope and prayer is that the Mass of St. Philip Neri might be one small flame in a similarly authentic renewal of sacred music, faith and culture that is so needed in the Catholic Church today!

Paul Jernberg Clinton, Massachusetts February 24, 2012

You shall sprinkle me, listen here

Lord, have mercy, listen here

Glory to God, listen here

Alleluia

Mystery of Faith

Holy, Holy, Holy

Lamb of God

[1] Musicam Sacram, Art. 59; quote from Sacrosanctum Concilium, Art. 23

[2] Sacrosanctum Concilium, Art. 121

[3] Comments by Pope Benedict during a concert conducted by Dominico Bartolucci, June 24, 2006.

[4] The word ‘profane’ here is used in its first meaning, which is ‘outside the temple’ (Gr. pro - fanus).

[5] Sacrosanctum Concilium, Art. 14

[6] Riccardo Muti interview with ANSA.IT, May 27, 2011

[7] John von Rhein interview with Muti in the Chicago Tribune, January 29, 2012

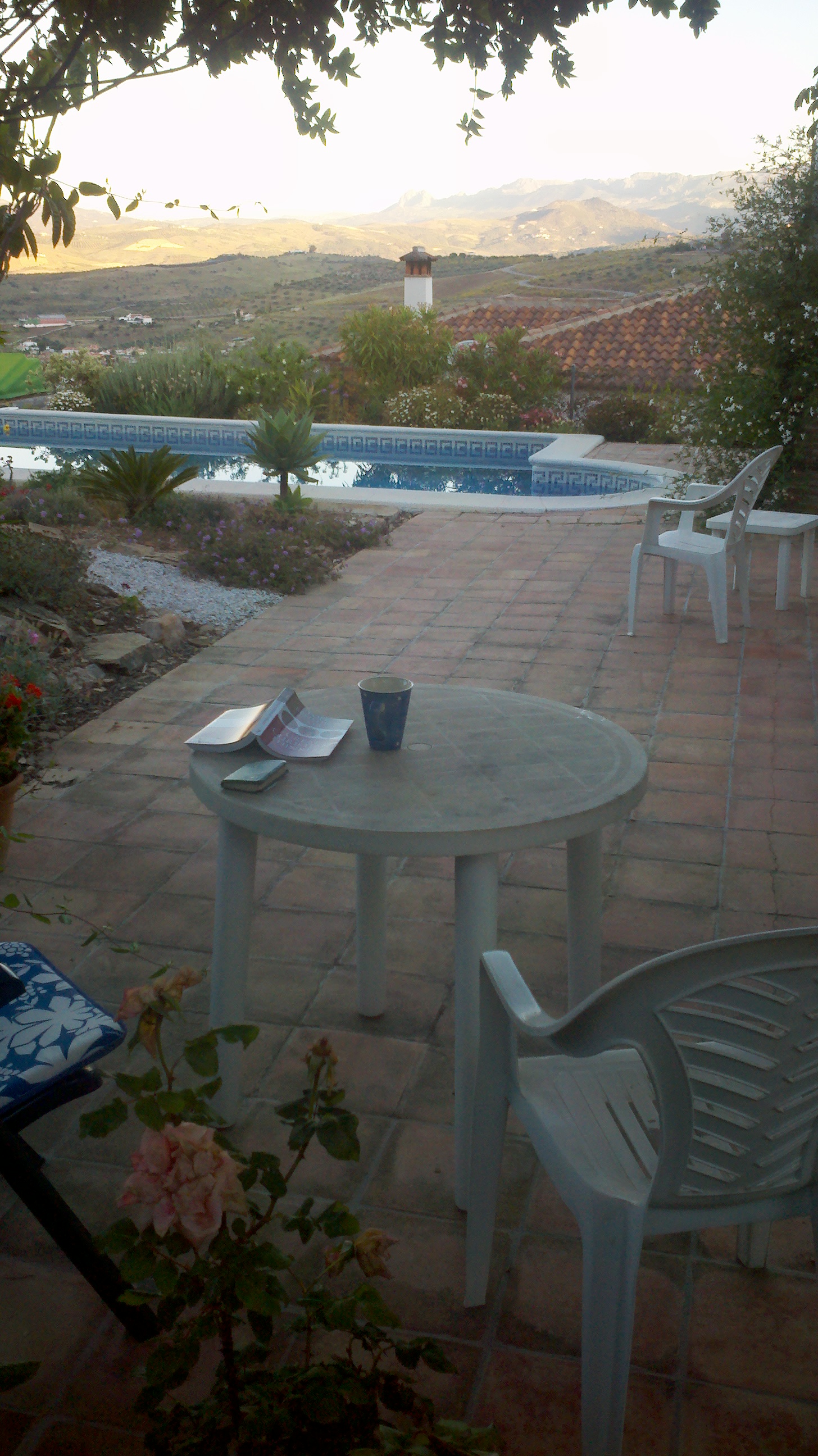

During my visit to friends and family in Europe, I spent a a few days in Spain (during the last week of May). My parents have retired there (along with another million Brits). I was lucky in that the time of my visit was just the time when wild flowers are in bloom. I am no plant expert, but I did recognise a lot from my memories of my parents' garden in England when I was growing up. So I asked them if they would help me identify some of the plants and we set off to high meadows to photograph and identify them.

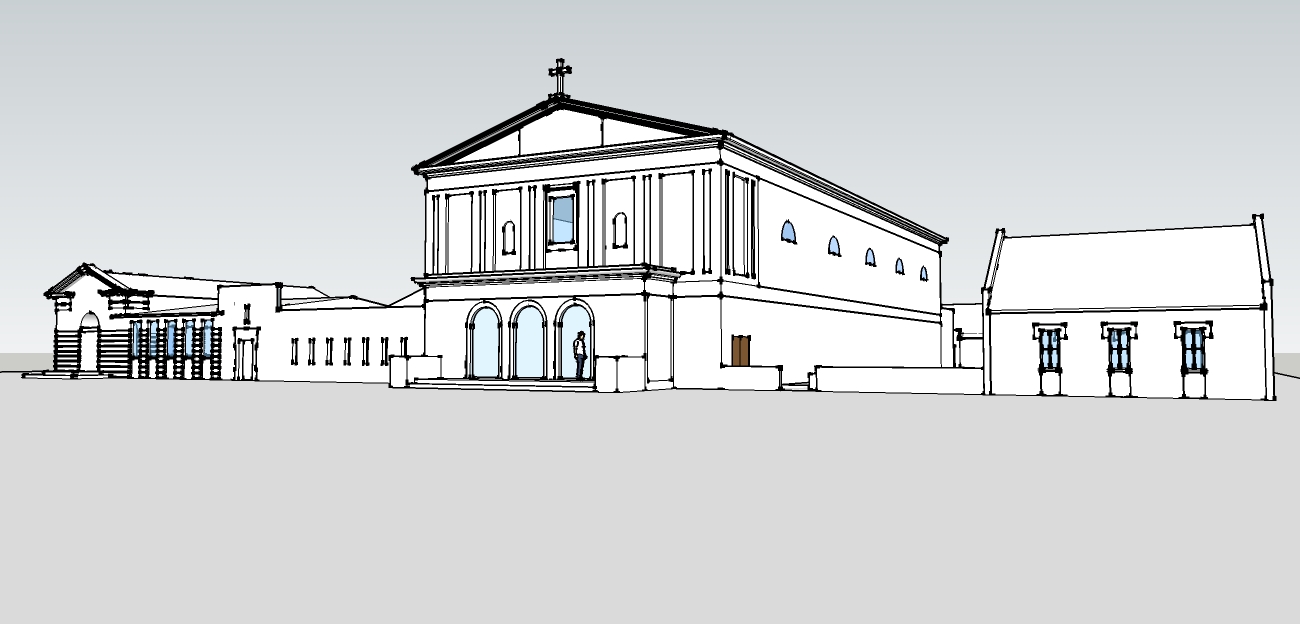

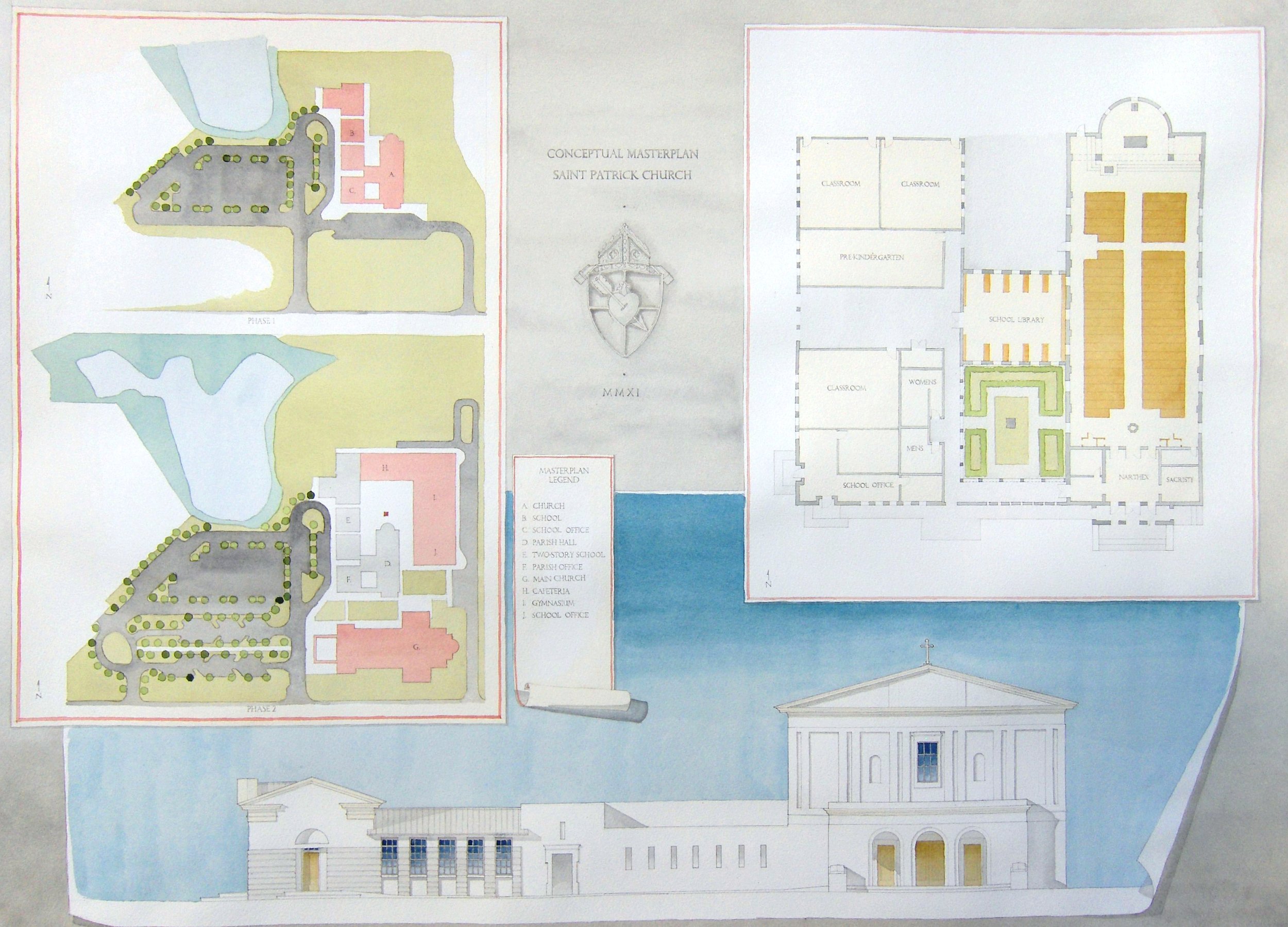

Also, I am trying to plant an English style perrenial garden in the farm that will be the new Thomas More College campus in Groton, Massachusetts. (I say 'will be' because we have to raise the money to build. This is not easy in the current economic climate, so please if anyone feels like donating, don't hesitate to contact us!) We have been following the planting scheme of the English garden designer Gertrude Jeckyll. From my first spring of planting here in the US, I recognised that many of the Spanish plants are in American gardens too. The photo above is of a thistle called echinops. We bought three to plant and they look pretty lonely at the moment while we wait for them to flourish and multiply. Here in Spain, there is a whole field of them next to my parents' house just growing wild.

During my visit to friends and family in Europe, I spent a a few days in Spain (during the last week of May). My parents have retired there (along with another million Brits). I was lucky in that the time of my visit was just the time when wild flowers are in bloom. I am no plant expert, but I did recognise a lot from my memories of my parents' garden in England when I was growing up. So I asked them if they would help me identify some of the plants and we set off to high meadows to photograph and identify them.

Also, I am trying to plant an English style perrenial garden in the farm that will be the new Thomas More College campus in Groton, Massachusetts. (I say 'will be' because we have to raise the money to build. This is not easy in the current economic climate, so please if anyone feels like donating, don't hesitate to contact us!) We have been following the planting scheme of the English garden designer Gertrude Jeckyll. From my first spring of planting here in the US, I recognised that many of the Spanish plants are in American gardens too. The photo above is of a thistle called echinops. We bought three to plant and they look pretty lonely at the moment while we wait for them to flourish and multiply. Here in Spain, there is a whole field of them next to my parents' house just growing wild. The fact that the whole terrain is formed by man raises a question in my mind. What is the natural environment for wild flowers? Would these flowers be here at all if it weren't for man? If there were no man affected areas, would there be any terrain for them to grow in? Certainly, the ones I saw don't grow in the areas that are wooded, only on the edges made by man. Perhaps there are some plant experts out there who can answer these points definitively. What I can say is that these flowers are flourishing in those areas affected by man. If this man-affected terrain is the natural environment for wild flowers, and wild flowers are considered part of the natural world (along with the insect life engendered), then we would have to consider man's activity natural too.

The fact that the whole terrain is formed by man raises a question in my mind. What is the natural environment for wild flowers? Would these flowers be here at all if it weren't for man? If there were no man affected areas, would there be any terrain for them to grow in? Certainly, the ones I saw don't grow in the areas that are wooded, only on the edges made by man. Perhaps there are some plant experts out there who can answer these points definitively. What I can say is that these flowers are flourishing in those areas affected by man. If this man-affected terrain is the natural environment for wild flowers, and wild flowers are considered part of the natural world (along with the insect life engendered), then we would have to consider man's activity natural too. We surveyed the scene, book in hand:

We surveyed the scene, book in hand: