I once heard a discussion on the radio about preparation for old age. The focus was on making sure that you had sufficient financial resources and so there was talk of the need for people to start making contributions to pension plans early. One person offered a slightly different approach. While putting money away for the future was not a bad idea, he said, people should think about what they are actually going to do when they retire, furthermore they should avoid getting into the trap of living the whole of their working lives as though its only purpose is to provide for retirement. Why not try to find a way of earning money that you enjoy, he said? Then you will want to work after the age of 65 because you enjoy it and so reduces the amount of money that one needs to save; and makes the time both before and after retirement more enjoyable. As he pointed out, there is danger of being so fearful of being able to support yourself after 65 that the whole of you life prior to it becomes a waiting game in which retirement is a sort of 'secular afterlife', a reward for the drudgery of work. He had a point, I think. Firstly, pension schemes are not guaranteed however prudently one saves. Also, it is good to think about what we can do to enjoy life, before and during retirement, as well as having the money to do it.

Given that my physical capabilities are going to decline with time, shouldn't I be ready to change what do as I get older so that life is always interesting. I am 52 and so am aware of this happening already. I am reminded of my grandpa here. While he did the same job all of his working life which he enjoyed until he was 65, he always had strong recreational interests as well. He was an nationally known rugby player until he was thirty, when I he gave up rugby and took up tennis and golf. For the next 20 years he played for the local tennis club and got a golf handicap of five. Then at the age of 50 he gave up tennis and golf and took up the even more sedate activity of bee-keeping, which he did until he died at the age of 83 (at the end he was recruiting neighbours and family members to help him move the hives onto the moors for the heather-honey season). Bee-keeping was the hobby that he followed for the longest time and which occupied him during all of his retirement.

Ultimately, our happiness in life rests on more than having hobbies, of course.; but the principle of anticipating how we change as we get older applies as much to consideration of doing what is right and good, I suggest. This is where, for the Christian, consideration of one's personal vocation comes in. If we find out what God wishes for us to do then we will be fulfilled and He will give us the means by which we can do it. I have written a number of articles on guidance that I was given and will repost one of these in the next couple of days.

In recent years I have seen a number of people approaching their last days and suffering from debilitating illnesses. This has made me think about the lives of those who cannot do anything without great help, cannot concentrate long enough on anything they observe to derive mental stimulation from it and cannot communicate with others easily. Is Christian joy on offer to them too? One has to believe so...but how?

It is distressing to see someone dying of cancer unable to do much more than watch television and eat when fed. I saw someone whom I loved slowly decline so that she was not able to concentrate or draw on her memory sufficiently well to engage in conversation. What made it worse was that she was aware of the decline in her mental abilities and was getting frustrated at not being able to respond and say what she wanted to. Unable to move without help, she was chair bound most of the day and would fall asleep periodically (perhaps under the effect of the pain controlling medication) and so could not even watch a television program long enough to follow what was going on and enjoy it.

I could not help trying to put myself in her place and imagine how life must be for her. How does one cope when there is little pleasure and continuous discomfort? It was a difficult question for me to answer, so I prayed that she could know that her family loved her. I prayed also that her capacity to respond to God's grace was always present, even as all other faculties decline in power. Then, I hoped, even in this last stage of life Christian joy can be hers too. Like the joy of the Christian martyrs who can inspire us, that there is a joy for her too that transcends the physical suffering and increasing isolation.

I have reflected also on what may be the future for me. Like any of us, it is quite possible that I will have to face such a situation myself. How would I fare? Is there any preparation anyone can make?

The only answer I could think of was a life of prayer, meditation ordered to participation in the liturgy. The Rule of St Benedict sets out one approach to such a life. As a Benedictine Oblate (of Pluscarden Monastery in Scotland) I have studied the Rule a little and have tried to adapt it a lay life.

A spiritual life should be focussed on the worship of God in the sacred liturgy and be a balance of participation in the liturgy itself, (the Mass and the Liturgy of the Hours); quasi-liturgical prayer, which is structured prayer that echoes the patterns or content of the liturgy, such as praying the psalms, repetitions of the Jesus Prayer or the rosary; and personal prayer. The liturgy is the activity from which all other human activity is derived and to which it ought to lead us. When this is understood, it makes all our everyday, common-or-garden activities fulfilling, while at the same ensuring that they don't become our primary goals in life.

In this context we can see that as we get older and our physical capabilities decline we will be forced to do things that are less physically demanding. If at this point we have developed the habits, then we will reach naturally for things that are in harmony with the principle of ordering our lives to union with God; and the activity of worship and prayer itself will start to occupy a greater proportion of our time, through default as well as desire.

For those I saw who were in their last days, even prayer becomes more difficult, they could not read a psalter, for example and gain anything from the text. What then? I remember being told of a lady who silently prayed the rosary all day in her chair. She could do this because the memory of it was indelibly imprinted on her mind through years of habit, so that her prayer was second nature, almost unthinking. This highlights the value of memorizing some set prayers when you can so that they are there to draw on later. I would go for some short psalms and the gospel canticles and the Jesus Prayer.

What if even the ability to do this has gone? It seems to me that contemplative prayer is what remains. Contemplation is a passive state of mind by which one is receptive to God's grace. In his Rule, St Benedict insists on the regular practice of lectio divina (you can read about how to do it in my book, the Little Oratory or in more detail in a great book on the subject by Dr Tim Grey). St Benedict describes the fourfold process: three are active - reading, meditating (thinking) and praying and the fourth is contemplation a passive, receptive state of mind that we are lead to by the practice of the first three. We do not judge the success of this, incidentally by how feel during the process or even by the number of good ideas that might, occasionally, jump into our heads. Grace is not felt directly.

For Benedict, the 'work of God' in which we participate is the liturgy, and so I have always understood lectio divina as a discipline that is part of a training that deepens our participation in the liturgy and so allows for a fuller union with God. In praying the liturgy we move from moment to moment engaging in one or other of these four processes and these constitute the dynamic of the exchange of love that is our goal.

It may be that the people who I have described and in whom even the possibility of active prayer and worship is reduced, that contemplation is the natural activity that occupies most time. I would like to think so, at least. I do not know of any reason to believe that the power of the faculty of the passive reception of God's love in contemplatio is impaired by old age.

There is no accounting for who will respond to His grace but, to the degree that any of us can develop that faculty, the answer seems to be to include the regular practice contemplative prayer in your prayer life now, would be an important preparation for a joyful old age.

I have been doing lectio divina daily this since I pondered over these things. I also try to put aside time when I can be 'alone with none but thee my God' - these are periods when I just try to sit and be aware of and enjoy being alive, devoid as much as possible from stimulation. It occurs to me that it would a useful to develop such as skill when there is discomfort and lots of distraction going on around me so that I can learn to cut it out. I will not always be able to control my environment and I might have to try contemplatio in a nursing room lounge when the television if showing Wheel of Fortune at a loud volume.

Another point is that the limitations I describe are not the preserve of the elderly. Some are born with severe physical and mental handicaps and it seems to me that they too might be unsung, natural contemplatives among us whose presence brings untold graces into the world for the benefit of all. As I understand it, God is not constrained by the sacraments and neither is He bound to act in ways that require mediation of the senses for us to benefit from them.

When all is said and done, we may be surprised to discover who has contributed the most to the good of the world and who has lived a life of Christian joy.

.jpg&container=blogger&gadget=a&rewriteMime=image%2F*)

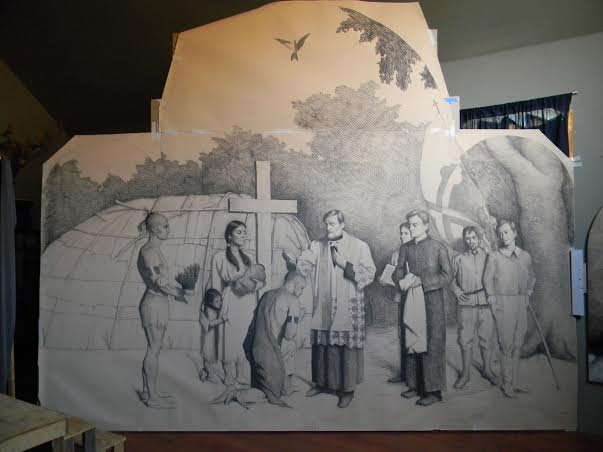

It was pure coincidence that this is the image that we were studying when I heard of Strat's death and then happened to read the above passage in his book.

It was pure coincidence that this is the image that we were studying when I heard of Strat's death and then happened to read the above passage in his book.

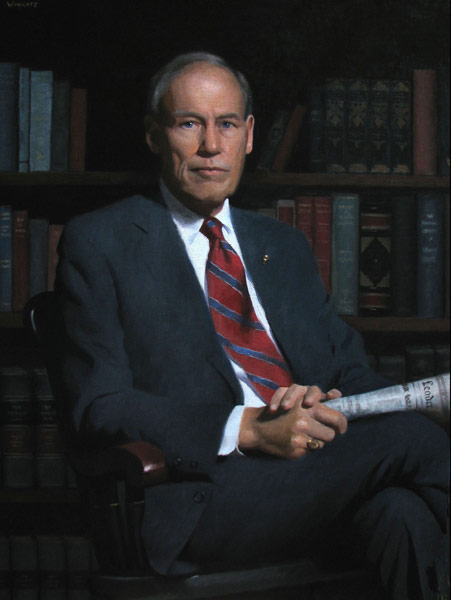

those of the principals hanging in the dining hall of a long-established school or college - I recently went to a dinner at the Roxbury Latin School in Boston - founded in the 17th century), you can see this difference between the traditional and the modern portraits very easily.

those of the principals hanging in the dining hall of a long-established school or college - I recently went to a dinner at the Roxbury Latin School in Boston - founded in the 17th century), you can see this difference between the traditional and the modern portraits very easily.

Drawing on people from the local Catholic parishes I would hope to start groups that meet for the singing of an Office - Vespers and or Compline or Choral Evensong and fellowship on a week night; and have talks on the prayer in the home and parish as described by the

Drawing on people from the local Catholic parishes I would hope to start groups that meet for the singing of an Office - Vespers and or Compline or Choral Evensong and fellowship on a week night; and have talks on the prayer in the home and parish as described by the