How doing what I want to do helps others to do what they want - a tribute to the outgoing President of the Dominican School of Theology and Philosophy in Berkeley, CA Several years ago, I attended a short lecture series offered by Fr Michael Sweeney, who was president of the Dominican School of Philosophy and Theology a member school of the Graduate Theological Union at Berkeley). It was called Re-Visioning Society and was offered as part of their summer session and explored Catholic social teaching and the common good. I am reminded of this now, in 2015, because I have stayed in touch with Fr Sweeney ever since. He has just stepped down from his role as President after 10 years. I am sure he will continue to have a profound affect people's lives in this next phase of his life. I hope also, of course, that the incoming President continues and even builds on the good work that has been going on at the school.

I was interested Fr Sweeney's course I because this idea of the common good has been referred to by Pope Benedict in a recent encyclical. What I didn't quite realize beforehand how important what I learned would be on my thinking subsequently. I was excited to realize, as happens so often when I learn more about one aspect of Catholic teaching, that it would have an impact on my understanding of everything else in the Faith. One of those in particular relates to the idea of personal vocation. I had written an article about discerning personal vocation just before this. Here is the article I wrote after the course, 5 years ago, in which (with the aid of Fr Sweeney's lectures) I hoped to place that idea of personal vocation in the context of God’s vocation for the whole human race, the common good:

How doing what I want to do helps others to do what they want - a tribute to the outgoing President of the Dominican School of Theology and Philosophy in Berkeley, CA Several years ago, I attended a short lecture series offered by Fr Michael Sweeney, who was president of the Dominican School of Philosophy and Theology a member school of the Graduate Theological Union at Berkeley). It was called Re-Visioning Society and was offered as part of their summer session and explored Catholic social teaching and the common good. I am reminded of this now, in 2015, because I have stayed in touch with Fr Sweeney ever since. He has just stepped down from his role as President after 10 years. I am sure he will continue to have a profound affect people's lives in this next phase of his life. I hope also, of course, that the incoming President continues and even builds on the good work that has been going on at the school.

I was interested Fr Sweeney's course I because this idea of the common good has been referred to by Pope Benedict in a recent encyclical. What I didn't quite realize beforehand how important what I learned would be on my thinking subsequently. I was excited to realize, as happens so often when I learn more about one aspect of Catholic teaching, that it would have an impact on my understanding of everything else in the Faith. One of those in particular relates to the idea of personal vocation. I had written an article about discerning personal vocation just before this. Here is the article I wrote after the course, 5 years ago, in which (with the aid of Fr Sweeney's lectures) I hoped to place that idea of personal vocation in the context of God’s vocation for the whole human race, the common good:

The questions I was hoping to resolve ran as follows: how can I act in ‘solidarity’ with the ‘common good’ and fulfill a personal vocation at the same time? Does acting for the common good mean that I have to think about how every action is in part, for example, going to contribute to alleviating famine in the world? Or, put another way, if I do nothing directly to help alleviate famine in Africa, am I ignoring my obligation to act in accordance with the common good? If either is so, it seems an impossibly high standard to achieve. Furthermore, won’t it likely undermine my success at doing anything well because I will have to spread myself too thinly – if I devote the time needed to teaching at Thomas More College, plus the other duties of life, I have none left to use directly to help those starving in the horn of Africa. Is this wrong? Am I being selfish in being and artist because I love doing it?

The course began by establishing from reason (as distinct from revelation) the nature of the human person as a relational being. We were simply asked to give a short summary of who we were for the other members of the class.

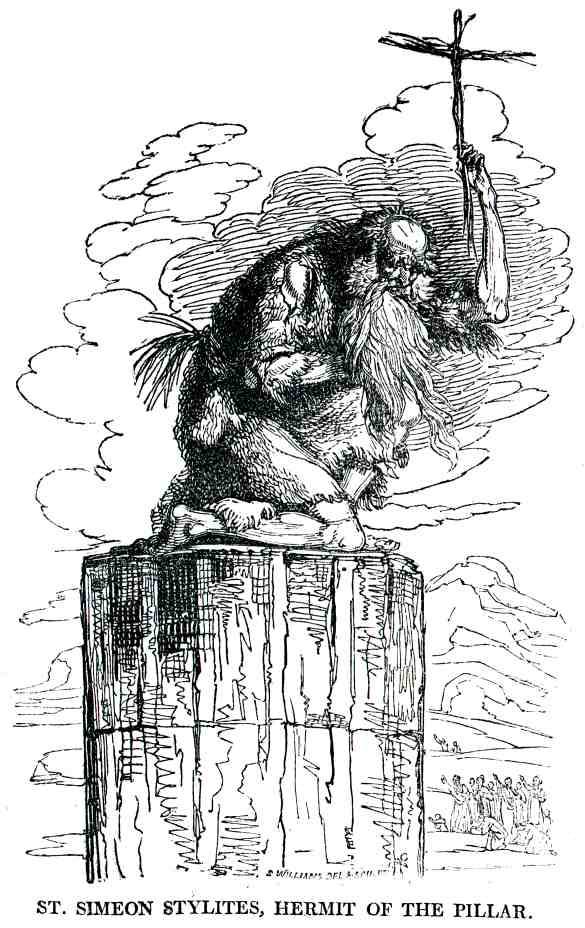

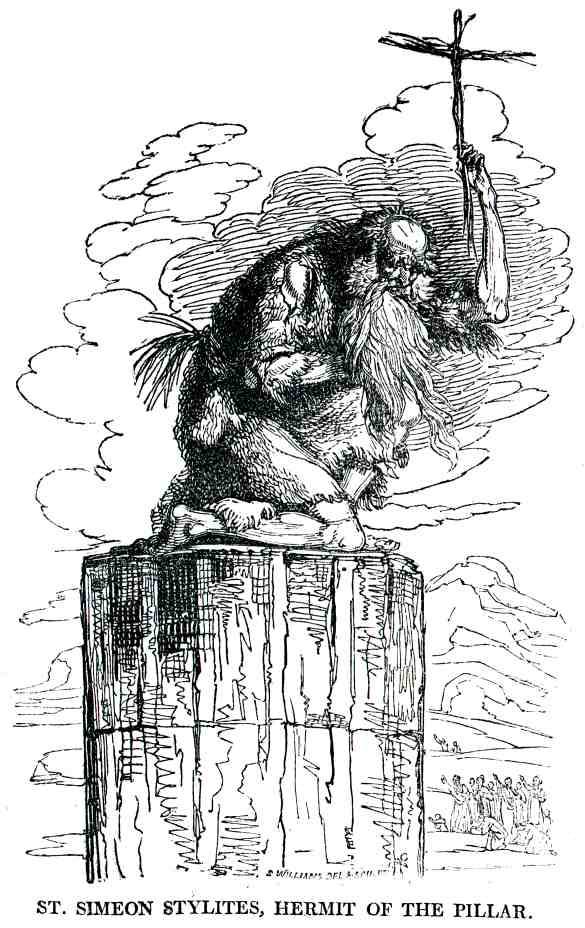

At this point I must admit I was wondering if I’d done the right thing in signing up for the class. Was it was going to degenerate into a touchy feely therapy? I needn’t have worried however. After allowing each of us to speak, Fr Sweeney then remarked on a common thread that ran through our descriptions of ourselves. Our own sense of ourselves was based upon relationships we have with others. (For example, ‘I work with this company’ ‘I do this job with these people’ ‘I am a father’) This is, we were told, what describes a person, as distinct from an individual. A human person is always in relation with others, starting from birth. No one, by choice, disengages from society altogether (not even a hermit) and is happy. From this starting point in common experience, he built up rationally, the case he was making, taking us with him…

This understanding of the human person has a profound effect on how we view what society is. A relationship of the sort we are now envisioning is always between two subjects ie two people freely cooperating as moral agents. This is termed covenantal and is based upon mutual self-sacrifice on behalf of the other. This freedom to respond as a person is one of the essential elements of society. Society therefore is the vector sum of the relationships within it. It is not a collective of self-contained individuals.

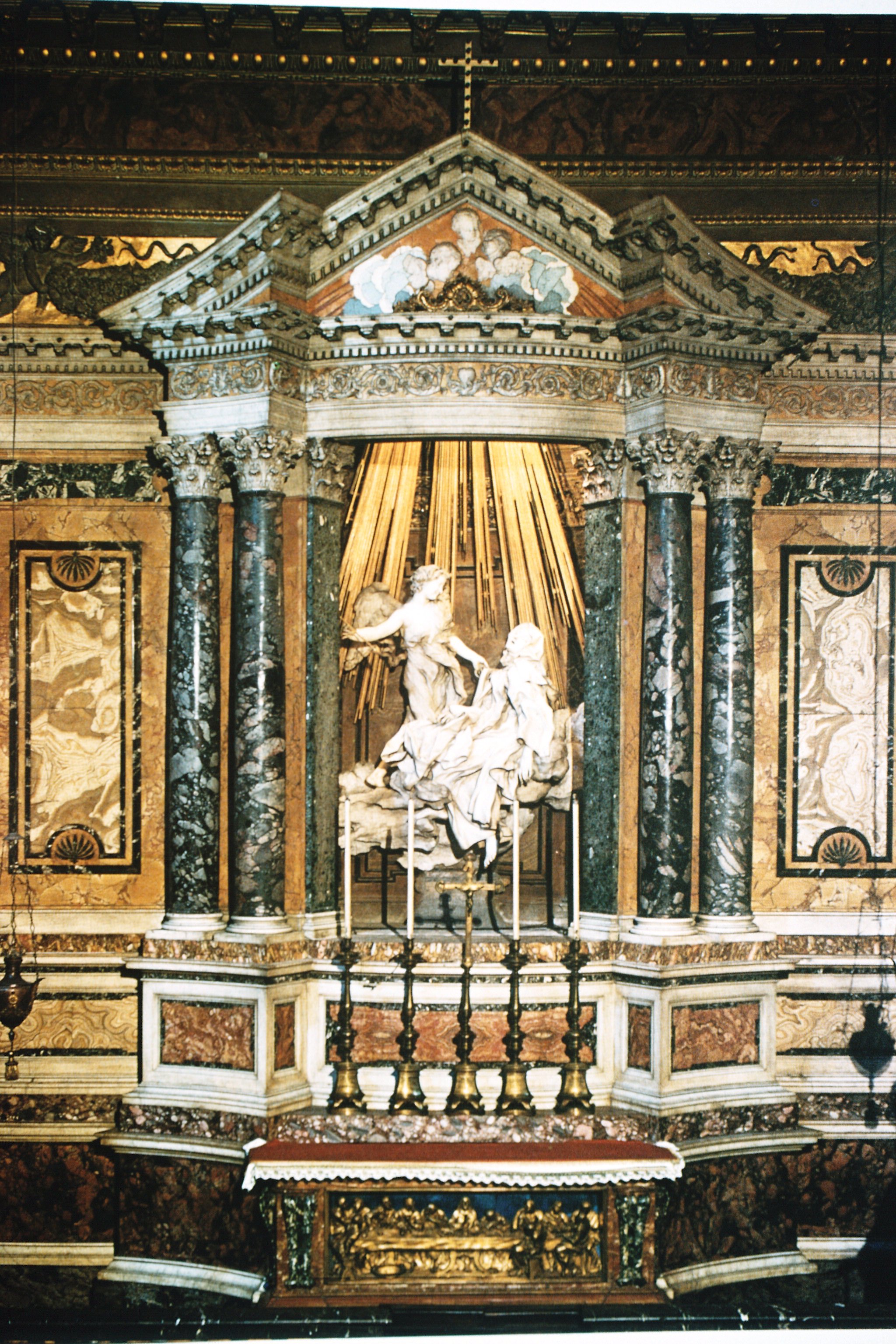

As with all things that exist in human nature, the essence of personhood exists in perfection in God in whose image and likeness we are made. However, there is only one God and unlike us He is complete unto Himself and does not rely on any external relationships in order to exist. Revelation helps us here: through it we know that there is one God and three persons in the Trinity, in perfectly realized relationship. This Christian concept of God also explains why we are liturgical beings, first and foremost. We are made for the liturgy, by which we approach the Father, through the Son, in the Spirit. When we participate in the liturgy we enter the Church, the mystical body of Christ. When we do so, with grace, we can relate first to the Son as man; and second to the Father through the Son as God. The Son is one person, but two natures.

If God were not like this, our relationship with him would be very different. A God who is not personal in the Christian sense would always be above us. We could not be raised to Him. Instead of a relationship of two subjects, it would be one of subject and object that is, master and slave. One can immediately see why Judeo-Christian society is fundamentally different from Islamic understanding of society, for example.

The good is what we seek and what makes us happy. We know from revelation objectively that this is God. This is the ultimate Good that is common to all of us. Society as a whole is called to be with Him in heaven and simultaneously, each person is called be with Him as well. On the way there are secondary goods that every one of us needs in order to be happy: food, shelter, water, air, love and so on. These are common goods.

So what of personal vocation and common good? God has called each of us to be with Him in heaven, as I described in my previous article, when we follow this we feel the joy that is ours. If we consider the vision that God has for society to be represented by a picture, then each personal vocation is a piece in the jigsaw that contributes to that picture. Therefore, we only need focus on our personal vocation and be content that it is contributing to the big picture and if perfectly realized would be in perfect harmony with it. This is not justifying selfishness. Every vocation is one of charity which permeates all that we do, but the precise way in which we are called to direct that charity is unique to each person. Some will be called to raise money for those who are starving. Some will not, but will be asked to. We are connected to society most profoundly through our closest personal relationships. So whatever these happen to be, these are the ones that we should focus on the most.

This of course, does rely on us being able to discern our vocation. We are fallen people and man’s ingenuity to hide bad motives behind good seems at times limitless. Therefore, good counsel is to be recommended during the discernment process.

When faced with a major choice we can ask ourselves a number of questions that help to point us in the right direction. First, is what I am doing consistent with its proper end? If so I am more likely to completing my piece of the jigsaw. Second (as a safeguard) is what I am proposing to do contrary to common good? Is it undermining others’ ability to respond freely in their relationships, for example; is it polluting the air so that it’s likely to harm those who breathe it. If so, I won’t do it.

Applied in business for example, other things being equal, I would act to make the business as profitable as possible, so that the gross profit was available to pay costs and employees, distribute amongst shareholders and reinvest for the continued profitability of the business. I would not feel obliged, for example, to institute charitable donations by the business to people that would be otherwise unconnected to the business model (although it would be perfectly good to take steps to enable shareholders and individuals to choose to contribute cooperatively in some way that they could not do as individuals). The general principle is that by fulfilling our personal vocation, we will be helping society as a whole to move towards the common good (and by refusing to do so, we tend to frustrate it).

I saying that each person's vocation is unique, what we are referring to is each person's unique way of attaining those goods that are common to all of us. And if in essence our vocation itself is common, and if the essential relationships through which it is expressed our common, then we are necessarily in solidarity with each other as we pursue our own vocation.

And what does this have to do with beauty? Beauty is what we perceive when there is harmonious relationships, sometimes called ‘due proportion’. In the context of human relationships, that is the harmonious alignment of wills on behalf of another and it is called love. An education in beauty is an education in love. It will increase our natural instinct for acting in accordance with the common good for the benefit of all. It starts with God’s love for us, already assured, and the degree to which we respond in kind, through grace.

As St Augustine said: ‘Love God and do what you want.’ And even if it means going to the desert and sitting on a pillar it is helping mankind...

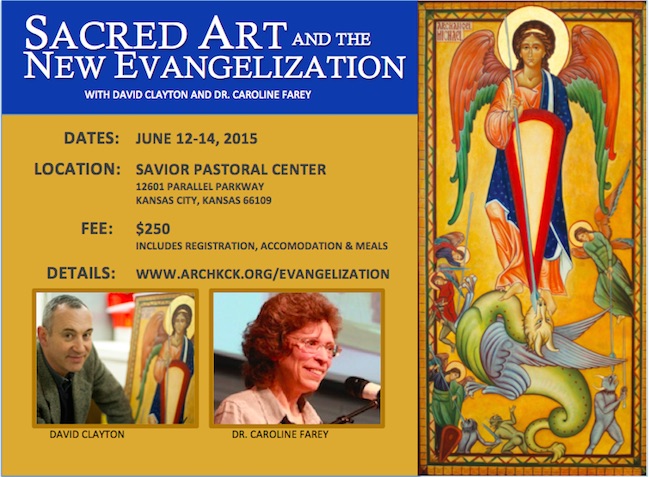

I have just been told about the news that Scott Hahn’s St. Paul Center for Biblical Theology has merged with Emmaus Road Publishing. They are also partnering with Lighthouse Catholic Media, who many will know for the recorded talks sitting in racks at the back of churches. Lighthouse will serve as their distributor for their products.

I am a great fan of all of Scott Hahn's books. He has a great gift for articulating what can ordinarily be quite dry and abstract subjects in a way that is accessible and interesting. His book the Lamb's Supper - the Mass as Heaven on Earth was a revelation (if you'll forgive the pun). It was the first time that the Book of Revelation had made any sense to me and it changed dramatically my whole idea of what the liturgy is.

I have just been told about the news that Scott Hahn’s St. Paul Center for Biblical Theology has merged with Emmaus Road Publishing. They are also partnering with Lighthouse Catholic Media, who many will know for the recorded talks sitting in racks at the back of churches. Lighthouse will serve as their distributor for their products.

I am a great fan of all of Scott Hahn's books. He has a great gift for articulating what can ordinarily be quite dry and abstract subjects in a way that is accessible and interesting. His book the Lamb's Supper - the Mass as Heaven on Earth was a revelation (if you'll forgive the pun). It was the first time that the Book of Revelation had made any sense to me and it changed dramatically my whole idea of what the liturgy is.