In his book the Wellspring of Worship, Jean Corbon (who also wrote the section on prayer in the Catechism) wrote the following: 'Work and culture are the place where men and the world meet in the glory of God. This encounter fails or is obscured to the degree that men "lack God's glory" (Rom 3:23)... If the experience is to be filled with glory, men must first become once again the dwelling places of this glory and be clothed in it; that is why, existentially, everything begins with the liturgy of the heart and the divinisation of the human person.' Elsewhere he states that an absence of communion through Eucharistic liturgy 'that is at the root of injustices in the workplace, with its alienating structures and disorders in the economy.' (pp 225, 229)

How can we change society and the culture into one that is beautiful, is just and is built on true community? I say, following on from Corbon, that if we wish to change society we look to ourselves first so that we become the people who are transformed in Christ - transfigured - and show him to others by our actions and interactions. Society is network of personal interactions, and we change society, therefore by changing the way we interact with others. There is no aspect of human life to which this does not apply.

Only God's grace can do this for us, and it is by prayer, or more precisely, by worship of God that we encounter Christ in such a way that it can happen. When we can be one of those people, then people will be drawn to the Church through us and join us. To the degree that anyone is participating in the divine nature and showing people the transfigured Christ in their daily lives, he is someone who, by grace, will relate to others in properly ordered love. This is what attracts people to the faith. This will be evident in the workplace as much as anywhere else. All economic interactions ought to be personal and loving as much as any other in a good society. In the sphere of economics this is how the principle of superabundance is invoked that creates prosperity for society. This principle of superabundance is the great untold secret for the creation for wealth; if it isn't actually the pearl of great price it will certainly give you means to buy it!

None of us should ignore this, for we are all involved in economic interactions of some sort and we all need to flourish and make sufficient wealth to live on. However, some people have a particular calling to be entrepreneurs. They have a special grace, an ability to make money beyond their personal needs and in a way that encourages human flourishing at all levels. When they do this they are participating in the creative work of God and contributing to the culture by creating something of beauty. However, for that calling to be realized, they need also to be aware of not only how to make money in a way that is in accord with the common good, but also, the end to which that money should be directed responsibly. They must be good stewards. It is the nature of charisms that unless they are directed in love, they evapourate, ie they cannot be misused. So while it is possible for someone to make money selfishly, or course, and also for people who do not have this particular calling to develop the skill of entrepeneurship and be driven by good motives. The person who has this charism, however, and special calling, will generate wealth almost effortlessly (compared to others) and in great abundance when does so in accordance with the principle of love.

Benedict XVI describes this ideal for personal interactions in economic activity in his encyclical, Caritas in veritate. It is a network of such personal interactions that in aggregate form a free society and the free economy described by John Paul II in Centesimus annus.

Benedict describes how Christians are transformed in Christ in this life by degrees and by grace - transfigured and participating in the divine nature - through a personal encounter with God in the Eucharist. To the degree that human relationships are driven by concern for the other person, they are in accordance with the Trinitarian dynamic of love that is the model for the loving component of personal relationships. When this Love is present it is always superabundant. Love is superabundant - fruitful without measure - because of the generosity of God who can give beyond all limitations and creates out of nothing. It is by this principle that wealth is generated in properly ordered economic transactions.

Though we may not think of it as such, the ordinary exchange of goods for money that we are daily engaged in does not redistribute wealth, it creates wealth. By this simple exchange both parties have something they value more than before and so wealth has been created (otherwise they would not both choose to make the exchange). There is a caveat. This is true provided that there is personal freedom (understood not simply as lack of constraint, but also full knowledge of the practicable best).

One of the beauties of the participating in the market in a free economy is that if I am dealing with someone in such a transaction who is genuinely free to choose whether or not he trades with me, then even if I am driven by selfish ends I am forced to consider his needs and what is good from his point of view. If I don't then the chances are that he will choose not to trade with me because he is free not to do so. So provided that freedom is present, even the selfish like me are forced to some degree at least into loving action. Even in this minimal form of love there is superabundance. In practice, rarely is someone wholly driven by selfish interests, just as it is rare that is someone wholly loving in action and thought. Superabundance is maximized to the degree that both parties are genuinely interested in the well being of the other as they engage in the transaction. This is when all the aspects for which a price cannot be paid - at a simple level a genuine care and attention, for example are given freely too. To the degree that the loving component grows then people relate to each other so that the other flourishes. When the conditions exist that allow for this to happen, people will naturally seek out others who interact in this way and the complexion of the economy gradually changes. Economic prosperity is maximized to the extent that the activity that creates it is in harmony with a flourishing of the society of human persons. When people are transformed in Christ, then they are more naturally inclined to consider the other in what they do and go beyond the simple contractual elements of trade, and create an economy that is rooted in a love which goes beyond the minimum requirement of justice.

One might refer to this as a covanental economy, one that is ordered to mutual giving, rather than one that is purely contractual and relies on the alignment of self-interest alone.

John Paul II pointed out in Centesimus annus that the market is the most efficient and best way to distribute goods for which a price can be paid. He then stated that this also defines the limitations of the market, it cannot distribute those things for which a price cannot be paid which are also vital in life and the flourishing of the human person. That is why he said that this market will be in the context of what he called a 'free economy'. Benedict in Caritas in Veritate connects the two much more directly in each economic transaction and says that unless those aspects for which money is not paid are present there too (he calls this additional element one of gratuitousness) then there is no superabundance. In fact he goes on to say that gratuitousness must be present if wealth is to be created.

When freedom is lacking - as it would be even in an otherwise free society in the case of an addict buying illegal drugs for example, the result is not the superabundant creation of wealth, but an enforced redistribution of wealth that favors one party more than the other inequitably. The party that gains is not just taking advantage of the other person in the exchange, but is parasitical upon society as a whole , drawing from it, rather than contributing to it; one only needs to look at a neighborhood in which drug dealing is rife to see the effects. Similarly, government taxation directed towards paying for activities that go beyond the natural role of government (which should be limited to the regulating for and protecting personal freedom) are also acts against the common good that go against freedom, are contrary to what a government's role should be and will have the stultifying effects on society as whole that we see, for example, in Venezuela today and we saw in the Eastern bloc countries of the past so markedly.

Benedict describes in many places in his writings how the personal transformation, by which a person is capable of and inclined to interact lovingly with his neighbors, will occur. Perhaps one of the most simply and concisely present examples is his little paper on the New Evangelization. We must first look at ourselves; we must learn to pray. It is through prayer, and to be precise a liturgically centered piety that we are transformed.

Not all prosperous societies are Catholic societies (whatever we mean by that) and not all Catholic societies are prosperous. But it is to the degree that any earthly city and its people participate in those ideals of the City of God, Catholic or not, that it is prosperous and stable.

It is the beauty of the culture, and especially the culture of Faith that will inspire Christians to pray well, and non-believers to pray at all. Beauty engenders creativity, inspires us to love and so to participate in the superabundant love in anything we do, including trade. This is why beauty, the free economy and the liturgy are inseparable.

People today yearn for community and for a beautiful culture that they feel is absent from their lives. This is not a new thing, this is what people have yearned for since their were people around to yearn for anything in life. The answer lies in each of us looking to ourselves. We must retreat to the wilderness symbolically in prayer, the place where Christ engaged with the devil, then transformed, we emerge and engage with our fellow man. We do not need to flee further at this point. We engage wherever we happen to be, wherever there are people. In doing so we will create the culture and the community we yearn for around us, where we are now, right here and right now. If this is not happening, then we look afresh at ourselves. While this mean that work becomes that of the artisan, like St Joseph, which we tend to romanticise today, we do not need to think that this is a process of turning back the clock. Rather it is one of adding to the workplaces that we are already in, the factory, shop, office, building site and so on and raising it up to a place of beauty and love.

Even in these workplaces, which are often seen as places that are opposed to Christian values, we can be that person, clothed in glory, who transforms those around them and transform the work culture. This is the message of the Church and of the New Evangelization. It begins with us being transformed in the liturgy and the hope is that after we engage with them we lead others back to the liturgy. It will be by the grace, beauty and love that others see in our work that they will let us do so.

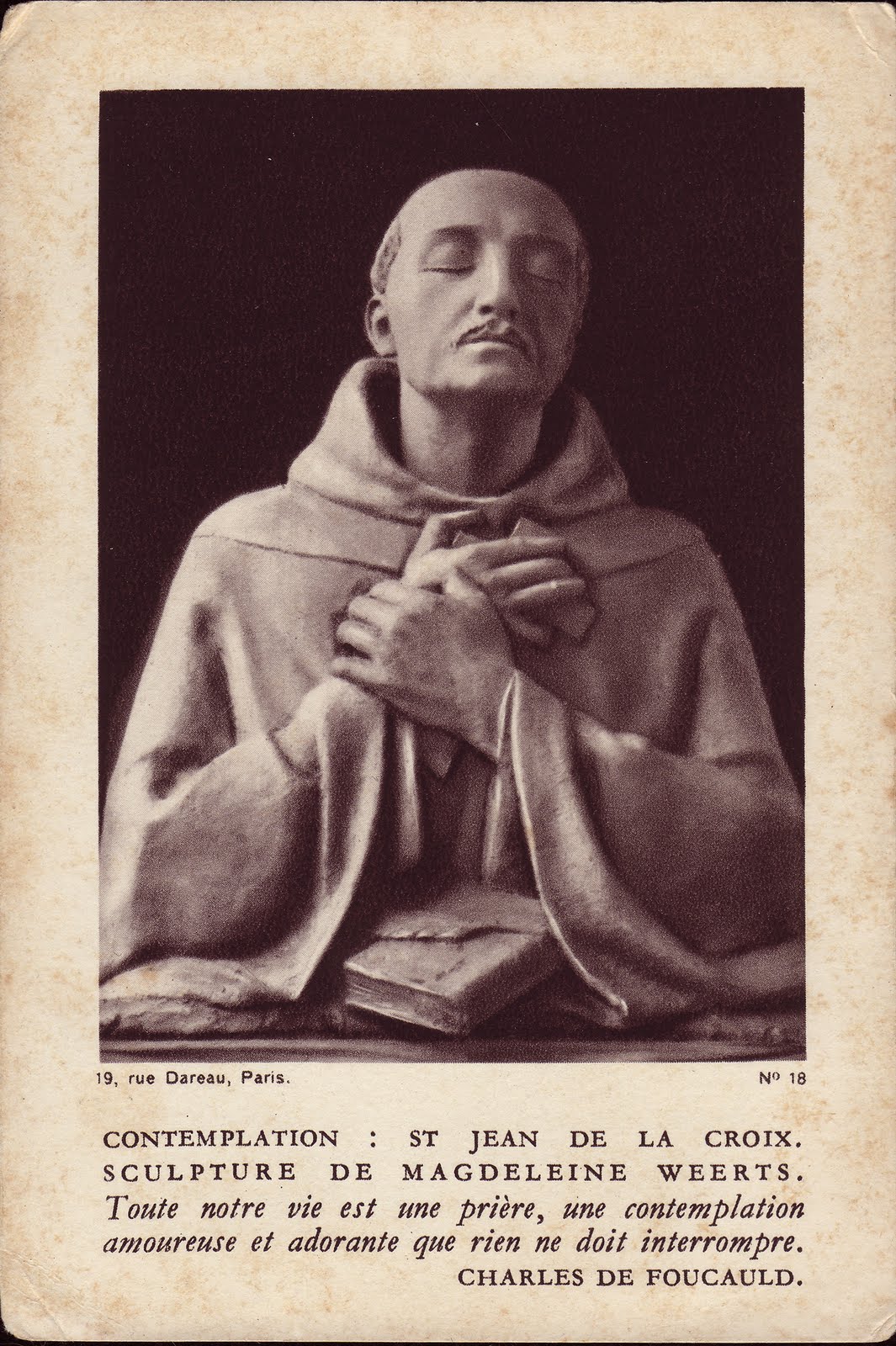

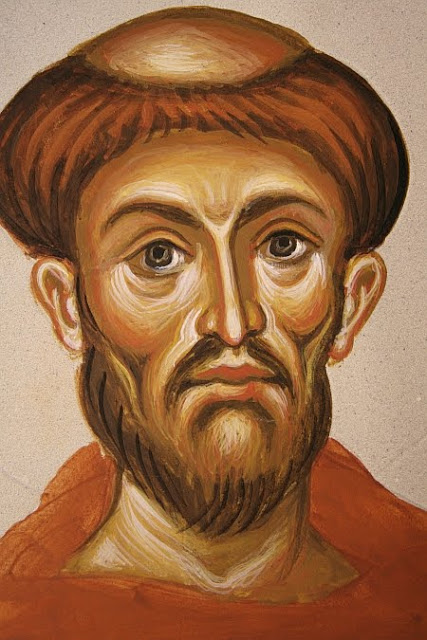

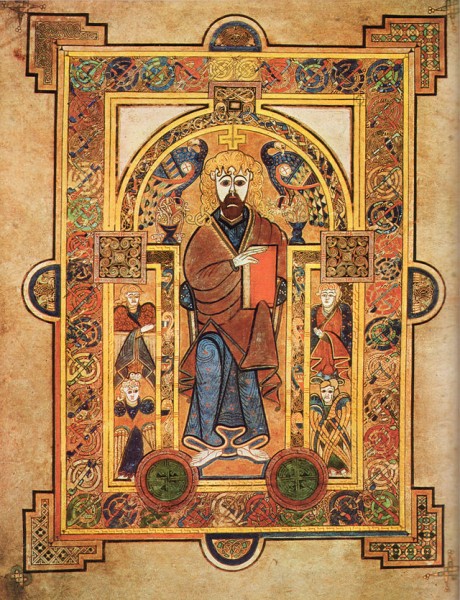

A word on the pictures: the first is Titian's Transfiguration, the second by the 20th century Italian artist Pietro Annigoni is St Joseph the Worker with Our Lord. The other three photographs are of a car production line, a NY trading floor and a clothes factory in India. It is easy in some ways to look back on the work of St Joseph as a carpenter and see this as participating in the Transfiguration, and this is reflected brilliantly by Annigoni. We tend to romanticise the work of the artisan nowadays and assume that somehow this work is intrinsically different from the work most people do today. This is why, supposedly, the factory worker is more alienated today than the agricultural worker of the 16th century. I am not persuaded of this. I think it depends as much on the people involved as the nature of the work. I suggest that we should not seek to eliminate or escape from the modern workplace, but work for its transformation with our participation in the liturgy at the heart of what we do. Then by our engagement with them, these places too can be in harmony with the life of the world to come. I hope that when we look back on the work of the sacred artist if the 21st century, it will portray saints on the trading floor with as much empathy as the man tilling the land; or the seamstress on the shop floor with the same light of grace as Our Lady sewing the curtains for the temple.

— ♦—

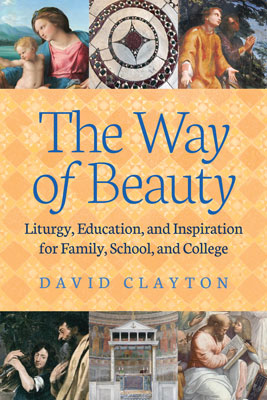

The book, the Way of Beauty is a manual for a formation in beauty that explains how the whole culture is a reflection of divine love, how we can become agents of that change as well as educators who can form offer that formation to others. It is available from Angelico Press and Amazon.

—JAY W. RICHARDS, Editor of the Stream and Lecturer at the Business School of the Catholic University of America said about it: “In The Way of Beauty, David Clayton offers us a mini-liberal arts education. The book is a counter-offensive against a culture that so often seems to have capitulated to a ‘will to ugliness.’ He shows us the power in beauty not just where we might expect it — in the visual arts and music — but in domains as diverse as math, theology, morality, physics, astronomy, cosmology, and liturgy. But more than that, his study of beauty makes clear the connection between liturgy, culture, and evangelization, and offers a way to reinvigorate our commitment to the Good, the True, and the Beautiful in the twenty-first century. I am grateful for this book and hope many will take its lessons to heart.”

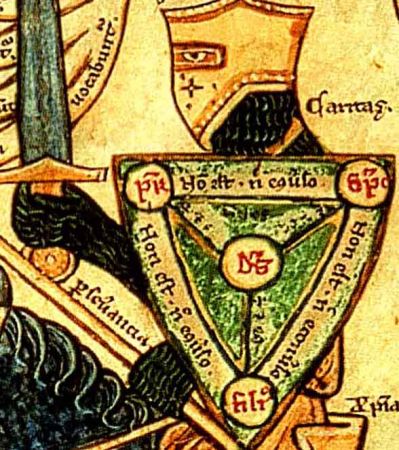

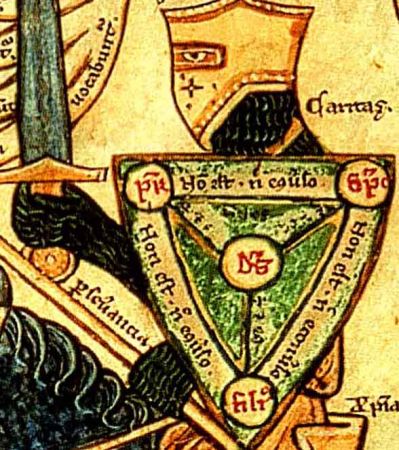

The Trinity Shield is a diagrammatical way of representing the Trinity. This is useful in couple of ways:

The Trinity Shield is a diagrammatical way of representing the Trinity. This is useful in couple of ways:

of the spirit to put itself in relation, the capacity to see itself and the other...the spirit is not merely there, it goes back on itself, as it were; it knows about itself. It constitutes a double existence which not only is, but knows about itself, has itself.' In icons, you often see faces portrayed with a slight lump or dimple in the middle of the forehead just above the bridge of the nose. This can be thought of as a symbol of the spirit. My teacher would refer to it with the Greek term, the nous, (meaning literally 'mind') and call it the the 'spiritual eye'.

of the spirit to put itself in relation, the capacity to see itself and the other...the spirit is not merely there, it goes back on itself, as it were; it knows about itself. It constitutes a double existence which not only is, but knows about itself, has itself.' In icons, you often see faces portrayed with a slight lump or dimple in the middle of the forehead just above the bridge of the nose. This can be thought of as a symbol of the spirit. My teacher would refer to it with the Greek term, the nous, (meaning literally 'mind') and call it the the 'spiritual eye'.

This access will also, I believe raise people's wonder at the beauty of cultivated land (whether ornamental garden or agricultural) and so perhaps help to offset the neopaganism that gives rise ultimately to the culture of death. When the only country landscape available to man is wilderness, and all else he sees is modern suburbia or a cityscape, then it reinforces the idea that the standard of beauty is that land which is untouched by man, that is wilderness. This in turn reinforces the idea that man's influence on nature is always detrimental and the natural extension of this idea is profound evil: the most effective way to restrict man's bad influence on nature, so the logic runs, is to restrict his activity through population control, which means contraception, abortion and euthanasia.

This access will also, I believe raise people's wonder at the beauty of cultivated land (whether ornamental garden or agricultural) and so perhaps help to offset the neopaganism that gives rise ultimately to the culture of death. When the only country landscape available to man is wilderness, and all else he sees is modern suburbia or a cityscape, then it reinforces the idea that the standard of beauty is that land which is untouched by man, that is wilderness. This in turn reinforces the idea that man's influence on nature is always detrimental and the natural extension of this idea is profound evil: the most effective way to restrict man's bad influence on nature, so the logic runs, is to restrict his activity through population control, which means contraception, abortion and euthanasia.