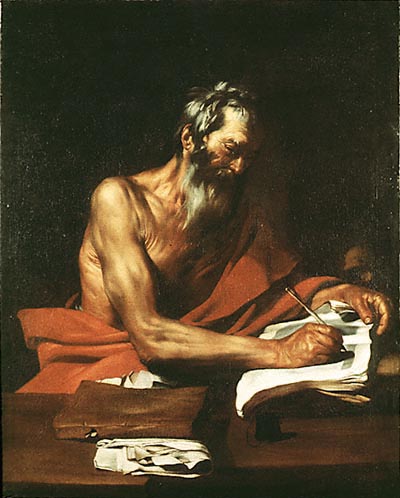

Choosing an Icon Class I would recommend that any Catholic artist, even those wishing eventually to specialize in more naturalistic styles, spend at least part of their training learning to draw and paint icons. The style of icons is so strongly and clearly governed by the theological message that it conveys that to learn this through the painting of them (as opposed to just learning about them) reinforces deeply the general point that form is important in Christian art, not just content. This is immensely helpful in trying to paint in, for example, the baroque style which is integrated also with theology but with a subtlety that can be missed if one is not alert to it. (Two short pieces on different aspects of this are here and here.)

There a number of places that one can go to learn icon painting, that I know of, both in the US and Europe. first and foremost I'm going to recommend doing a summer school at Thomas More College in New Hampshire, of course. Here are some things that strike me as worth considering when choosing such a place. I use my own experience of having classes with various teachers before settling on one whom I felt was right.

Choosing an Icon Class I would recommend that any Catholic artist, even those wishing eventually to specialize in more naturalistic styles, spend at least part of their training learning to draw and paint icons. The style of icons is so strongly and clearly governed by the theological message that it conveys that to learn this through the painting of them (as opposed to just learning about them) reinforces deeply the general point that form is important in Christian art, not just content. This is immensely helpful in trying to paint in, for example, the baroque style which is integrated also with theology but with a subtlety that can be missed if one is not alert to it. (Two short pieces on different aspects of this are here and here.)

There a number of places that one can go to learn icon painting, that I know of, both in the US and Europe. first and foremost I'm going to recommend doing a summer school at Thomas More College in New Hampshire, of course. Here are some things that strike me as worth considering when choosing such a place. I use my own experience of having classes with various teachers before settling on one whom I felt was right.

I was very lucky to be taught icon painting by an English iconographer called Aidan Hart. Firstly, he is a great icon painter: his icons are, in my opinion, as beautiful as any being painted today that I have seen. Second, he is a natural teacher. His is the model I look to when I try to teach others. As he demonstrated any particular skill, he emphasized the importance of understanding why things were done as they were, and reduced things down to a few core principles, which he sees as the unbreakable guidelines that define the tradition. This is in contrast to rules; which are the applications of the principles in particular cases. Understanding principles allows for the development of a living tradition which can develop and adapt to its time and place. The principles can be re-applied, perhaps to differing result, in different cases as need demands. So the rules change but the principles don’t.

I was very lucky to be taught icon painting by an English iconographer called Aidan Hart. Firstly, he is a great icon painter: his icons are, in my opinion, as beautiful as any being painted today that I have seen. Second, he is a natural teacher. His is the model I look to when I try to teach others. As he demonstrated any particular skill, he emphasized the importance of understanding why things were done as they were, and reduced things down to a few core principles, which he sees as the unbreakable guidelines that define the tradition. This is in contrast to rules; which are the applications of the principles in particular cases. Understanding principles allows for the development of a living tradition which can develop and adapt to its time and place. The principles can be re-applied, perhaps to differing result, in different cases as need demands. So the rules change but the principles don’t.

Once this was understood it was easier to see how there is a huge scope for variety in style of icons, without deviating from the central principles that make an icon and icon. It was he who pointed out to me the common elements that unite the various Eastern and Western Catholic traditions in iconography (and which I wrote about in more detail here). An understanding of principles allows for change without compromise of those principles; this is what is necessary in all traditions if they are to flourish.

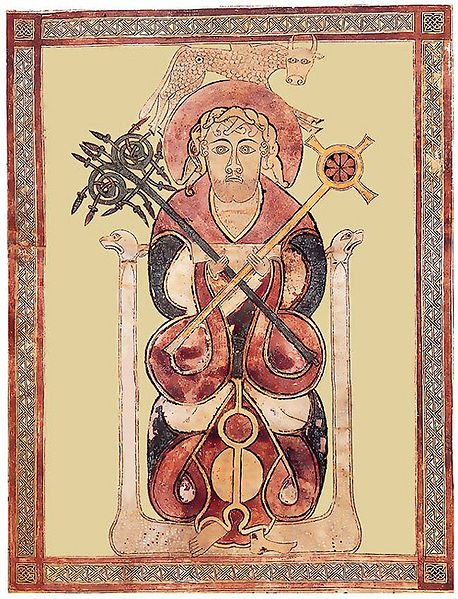

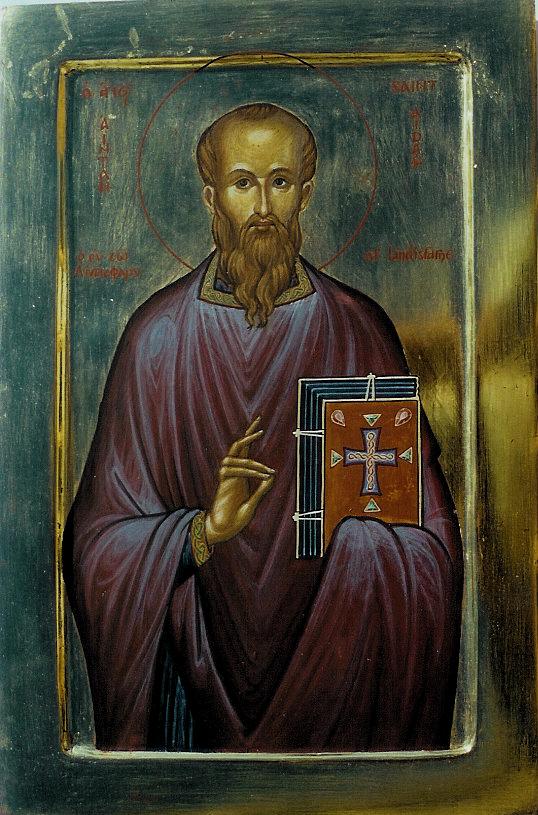

He had a particular interest in this, because living in England, he was exploring ways of painting icons of the ancient saints of the British Isles in a way that was simultaneously true to both the timeless and ‘placeless’ principles of iconography; and rooted in the geographical location and times of their lives. He tended to draw on the style that was seen in Constantinople and the Greek Church about 800-1,000 years ago. This is the style this has a higher degree of naturalism than we see in, for example, Russian icons, and, as I see it, is more accessible to the modern Western eye. The painting at the top of the article is of Saint Winifred. St Winifred’s well in North Wales is a British Lourdes, a place of pilgrimage still, where there are miraculous cures. The town which contains the well is called Holywell and there is still flowing spring and a 15thcentury gothic building that houses it. I have included below some more pictures of his saints of the British Isles. I have a particular fondness for this, I grew up on the English side of the border with Wales about 10 miles from the well and she is the patron of the local Catholic church. I have not spoken to Aidan about this directly, but I am guessing that when he painted it he was thinking of an icon of St Theodosia painted in Constantinople in the 13th century.

He had a particular interest in this, because living in England, he was exploring ways of painting icons of the ancient saints of the British Isles in a way that was simultaneously true to both the timeless and ‘placeless’ principles of iconography; and rooted in the geographical location and times of their lives. He tended to draw on the style that was seen in Constantinople and the Greek Church about 800-1,000 years ago. This is the style this has a higher degree of naturalism than we see in, for example, Russian icons, and, as I see it, is more accessible to the modern Western eye. The painting at the top of the article is of Saint Winifred. St Winifred’s well in North Wales is a British Lourdes, a place of pilgrimage still, where there are miraculous cures. The town which contains the well is called Holywell and there is still flowing spring and a 15thcentury gothic building that houses it. I have included below some more pictures of his saints of the British Isles. I have a particular fondness for this, I grew up on the English side of the border with Wales about 10 miles from the well and she is the patron of the local Catholic church. I have not spoken to Aidan about this directly, but I am guessing that when he painted it he was thinking of an icon of St Theodosia painted in Constantinople in the 13th century.

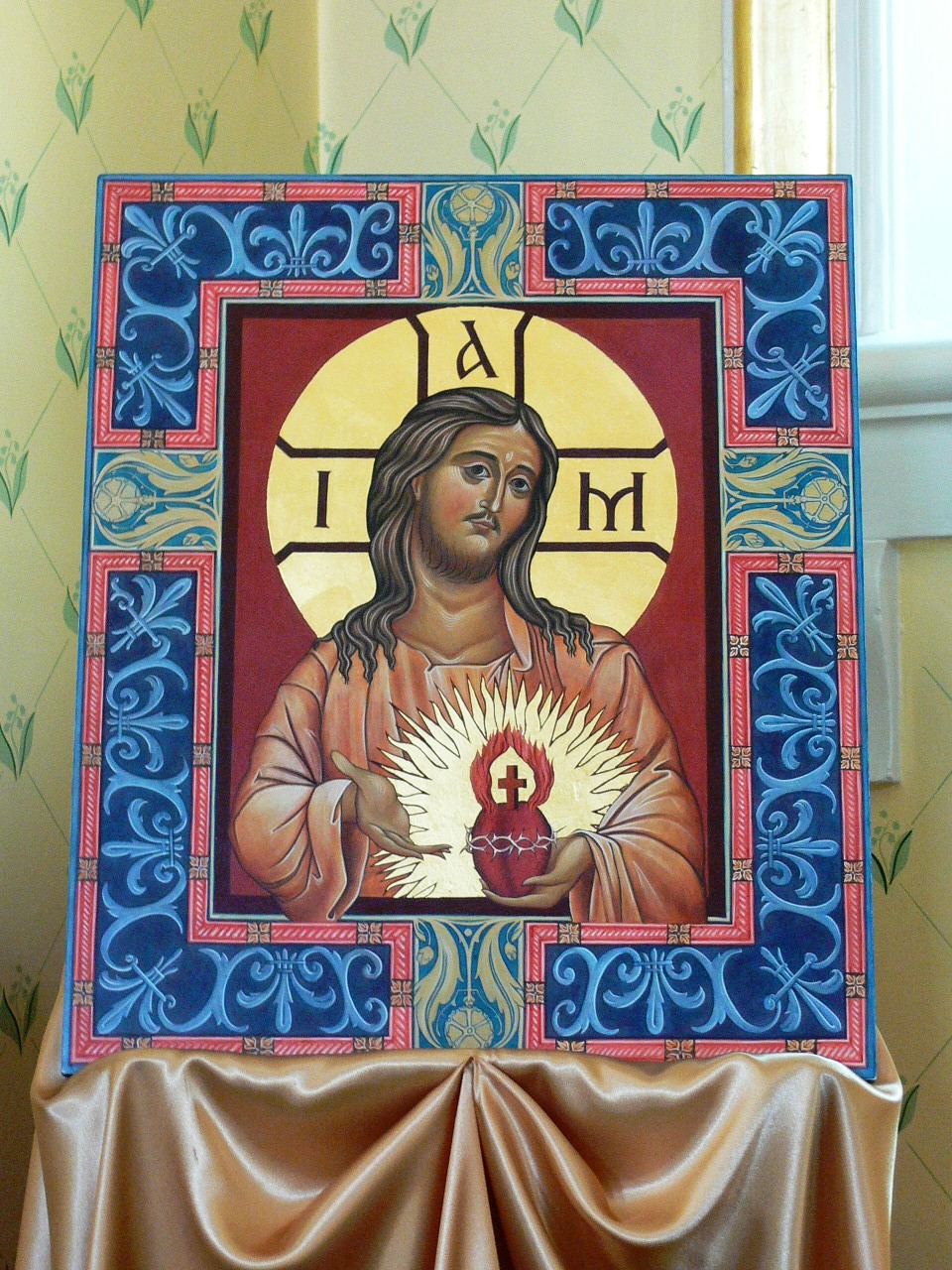

Inspired by this, when I seek to paint in the iconographic form, I look to our Western forms that grew up in the Roman Rite. For example, rather than have a plain raised border, I paint abstract patterned borders and backgrounds, taking inspiration from the Romanesque. (I wrote about this particular variation previously in Why Frame a Picture?)

It is important that Catholics who learn to paint icons place this artistic form within the context of our own tradition. If learning from any Orthodox teachers (which is likely), it should be remembered that Orthodox churches do not view Western non-iconographic liturgical traditions as legitimate forms of sacred art. As Catholics we do not need to be worried by this. We are not bound to accept all we are told uncritically, and as long as we know the basis of our own traditions well, we can make a sound judgment regarding the validity of what we are told.

It is important that Catholics who learn to paint icons place this artistic form within the context of our own tradition. If learning from any Orthodox teachers (which is likely), it should be remembered that Orthodox churches do not view Western non-iconographic liturgical traditions as legitimate forms of sacred art. As Catholics we do not need to be worried by this. We are not bound to accept all we are told uncritically, and as long as we know the basis of our own traditions well, we can make a sound judgment regarding the validity of what we are told.

If any of who can get to Shropshire in England, then consider signing on for his workshops here. He is very generous in his advice and happy to critique work and answer questions between workshops, so it is possible to make progress in between. This is the route that I took. (He also teaches a diploma in icon painting offered by the Prince of Wales's School of Traditional Art, which you might like to investigate, but there is such a waiting list you'll have to wait until 2013!)

If you cannot get to Shropshire, then there will soon be an alternative. I am excited that he will also bring out an instruction book on painting icons, which will be published by Gracewing. I have seen previews of significant parts of it and it is excellent, better by far than anything I have seen on the market. When it comes out I am sure to feature it. (He was hoping to raise money for an instructional DVD to accompany the book, so if anyone feels like contributing, please feel free to contact him through his website or the publisher!)

Scenes below are of St Winifred's Well at Holywell in North Wales, the 15th century housing and the well itself. Apart from St Theodosia above, all icons are by Aidan Hart, including a second St Winifred.