The model of loving compassion for others who are suffering. September the 15th was the Feast of Our Lady of Sorrows. I found the liturgy of the Church on this day very instructive and inspirational. The message I get from this is for me, powerful, vigorous and inspiring. The writing of St Paul and St Bernard on the matter speaks of virtue in the fullest sense of the word.

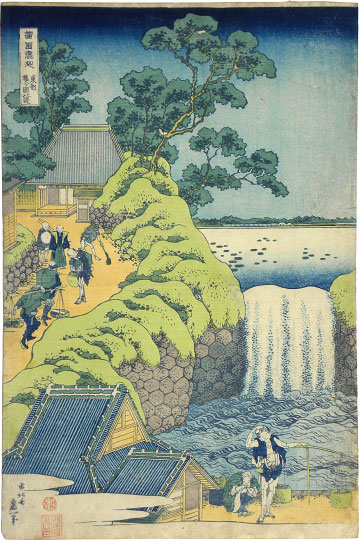

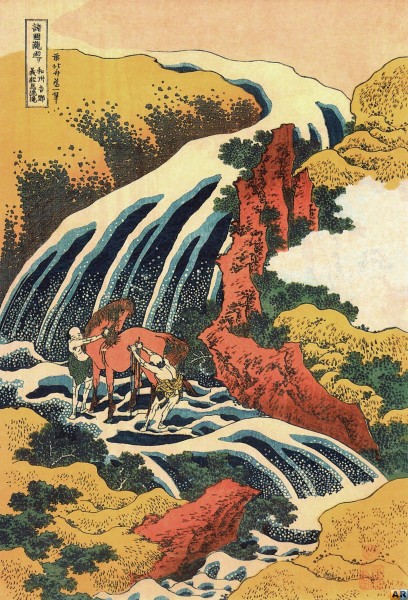

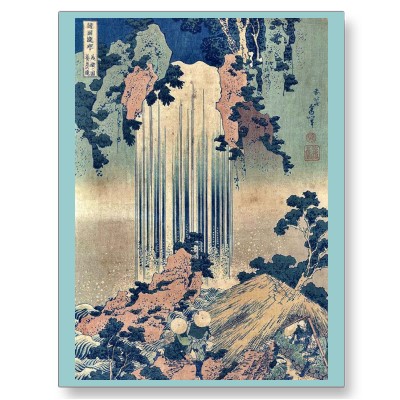

It is interesting to me that so much modern devotional art of Our Lady of Sorrows - Mater Dolorosa - is, to my eye, almost all sentimental and weak. The Spanish baroque and the Flemish gothic masters are for me the model of portraying negative emotion transcended with joy that is powerful yet calm.

The model of loving compassion for others who are suffering. September the 15th was the Feast of Our Lady of Sorrows. I found the liturgy of the Church on this day very instructive and inspirational. The message I get from this is for me, powerful, vigorous and inspiring. The writing of St Paul and St Bernard on the matter speaks of virtue in the fullest sense of the word.

It is interesting to me that so much modern devotional art of Our Lady of Sorrows - Mater Dolorosa - is, to my eye, almost all sentimental and weak. The Spanish baroque and the Flemish gothic masters are for me the model of portraying negative emotion transcended with joy that is powerful yet calm.

One of the most difficult things to deal with in life is the grief we feel when someone whom we love is suffering and we are powerless to do anything about it.

My experience tells me that this can have two components. That born of self-centredness, which is a bad feeling; and one born of love, which is opens the door to intense joy. It is this latter point that has come home to me through the liturgy on this feast day by pointing to the model of Our Lady.

When I am driven by self-centredness, I look at the person who is suffering and I feel sorry for myself. This self-pity can be intense and almost unbearable as long as I see the other's suffering as the cause of my anguish. The cause is my personal response, and I have some control over that. It is easy to decieve myself and think that this is an expression of love, but such empathy can very easily be rooted in self-centredness and be profoundly destructive to my life, while doing nothing to help the other person either. If I put myself in the other person's shoes through my imagination, I might do this so vividly that I feel sorry for myself. At a mild level this is why I feel embarrassed for someone if he makes a fool of himself in front of many people. I am not so much concerned for him, but rather imagining myself in his position so that I feel the self-pity that I would feel if I were in his shoes. Hence the discomfort.

At a deeper level, when someone we love is the author of his own suffering, perhaps an alcoholic or a drug addict, then our suffering can be driven not so much by the loving reaction of ‘how can you do this to yourself?’ but rather, ‘how can you do this to me?’. If there is a sense that the suffering is as a result of fate, then we can find ourselves directing that resentful complaint to God.

One way of dealing with this that I have heard of is to stop the habit of imagining ourselves in the shoes of the other. This is not always a good thing. A cold, uncaring detachment is heartless and shuts out all joy in our lives too. It is a response that lacks both empathy and sympathy.

There is a different sort of detachment in which we do not empathise, but we do sympathise with the suffering and act with love. So we act lovingly towards the other, but do not share in the emotions that they are experiencing as we do it. I have heard this described by some as ‘detaching with love’. Certainly this is greatly preferable to the self-centred anguish that causes us to feel sorry for ourselves when others are suffering. For many of us this may be the best approach for us to aim for, particularly if we are trying to break out of the bad habit of an instinctive reaction of a self-pity – empathy based upon self-centredness - to the suffering of others. When we become aware of the root of our emotions, it is certainly possible to develop an habitual attitude of mind that corresponds to this. In the ideal however, this would be a route to another, higher response which is one of a loving empathy. This is where Our Lady is the model.

There is a different sort of detachment in which we do not empathise, but we do sympathise with the suffering and act with love. So we act lovingly towards the other, but do not share in the emotions that they are experiencing as we do it. I have heard this described by some as ‘detaching with love’. Certainly this is greatly preferable to the self-centred anguish that causes us to feel sorry for ourselves when others are suffering. For many of us this may be the best approach for us to aim for, particularly if we are trying to break out of the bad habit of an instinctive reaction of a self-pity – empathy based upon self-centredness - to the suffering of others. When we become aware of the root of our emotions, it is certainly possible to develop an habitual attitude of mind that corresponds to this. In the ideal however, this would be a route to another, higher response which is one of a loving empathy. This is where Our Lady is the model.

The highest response to the suffering of others is a compassionate grief; and this one that is transcended by joy. This is the grief felt by Our Lady at the foot of the cross as she gazed at her suffering Son. It is an anguish born of love and as with all that arises from love it opens our hearts so that we can have a fuller union with God and experience an even greater joy.

In order for me to try to understand this, I had first to consider the situation when I am the one who is suffering directly, rather than worrying about the suffering of another. I know that God always gives us grace to deal with any situation and through cooperation with His grace, we can transcend any injustice and any suffering. When this occurs the suffering is not necessarily removed, but is as likely to be overwhelmed by the sheer joy of experiencing God’s consoling love. The writings of the saints indicate just how powerful this joy in suffering is. In order to experience this, I must first remove any self-centred feelings and resentment that I may have.

If that consolation is there for us when we are experiencing suffering directly, then it is there too when we experience pain or injustice indirectly, arising from and empathetic sharing in the suffering of others.

However, this is true only to the degree that our anguish arises from love. It if arises from a self-centred desire to right the suffering of others then we shun God’s grace. We must first free ourselves of that resentful attitude and to do this one might have to go back a step and adopt the ‘detach with love’ approach. When our anguish is a sharing in the suffering of others born of love for them, then it is a sharing also in Christ’s suffering on the cross. It is holy suffering that opens the door to a greater joy.

The Church’s liturgy on the Feast of Our Lady of Sorrows is very instructive on this. In the readings of the day there is a long passage from a sermon of St Bernard of Clairvaux. He describes Our Lady’s anguish at the foot of the cross as real, but arising from a genuine compassion that is born of charity ie love. He calls it a ‘martyrdom of the soul’: “We rightly speak of you as more than a martyr, for the anguish of mind you suffered exceeded all bodily pain.'Mother behold your son!' These words were more painful than a sword thrust for they pierced your soul and touched the quick where the soul is divided from the spirit. Do not marvel brethren, that Mary is said to have endured a martyrdom in her soul. Only he will marvel who forgets what St Paul said of the Gentiles that among their worst vices was that they were without compassion. Not so with Mary! May it never be so with those who venerate her. Someone may say: ‘Did she not know in advance that he Son would die?’ Without a doubt. ‘Did she not have sure hope in his immediate resurrection?’ Full confidence indeed. ‘Did she then grieve when he was crucified?’ Intensely. Who are you brother, and what sort of judgment is yours that you marvel at the grief of Mary any more than that the Son of Mary should suffer? Could he die bodily and she not share his death in her heart? Charity it was that moved him to suffer death, charity greater than that of any man before or since: charity too moved Mary, the like of which no mother has ever known.’(From the Office of Readings, Feast of Our Lady of Sorrows)

The Church’s liturgy on the Feast of Our Lady of Sorrows is very instructive on this. In the readings of the day there is a long passage from a sermon of St Bernard of Clairvaux. He describes Our Lady’s anguish at the foot of the cross as real, but arising from a genuine compassion that is born of charity ie love. He calls it a ‘martyrdom of the soul’: “We rightly speak of you as more than a martyr, for the anguish of mind you suffered exceeded all bodily pain.'Mother behold your son!' These words were more painful than a sword thrust for they pierced your soul and touched the quick where the soul is divided from the spirit. Do not marvel brethren, that Mary is said to have endured a martyrdom in her soul. Only he will marvel who forgets what St Paul said of the Gentiles that among their worst vices was that they were without compassion. Not so with Mary! May it never be so with those who venerate her. Someone may say: ‘Did she not know in advance that he Son would die?’ Without a doubt. ‘Did she not have sure hope in his immediate resurrection?’ Full confidence indeed. ‘Did she then grieve when he was crucified?’ Intensely. Who are you brother, and what sort of judgment is yours that you marvel at the grief of Mary any more than that the Son of Mary should suffer? Could he die bodily and she not share his death in her heart? Charity it was that moved him to suffer death, charity greater than that of any man before or since: charity too moved Mary, the like of which no mother has ever known.’(From the Office of Readings, Feast of Our Lady of Sorrows)

Following this is a quote from St Paul in his Letter to the Colossians in which he says directly that this sharing in Christ’s sufferings through love is a source of happiness: ‘It is now my happiness to suffer for you. This is my way of helping to complete, in my poor human flesh, the full tale of Christ’s afflictions still to be endured, for the sake of his body which is the Church.’(Col 1:24-25).

The antiphon for the Benedictus on Lauds for that day echoes this and takes it even further: ‘Rejoice grief stricken Mother, for now you share in the triumph of your Son. Enthroned in heavenly splendor, you reign as queen of all creation.’

The idea of 'bright sadness' is often associated with the expression of saints in icononographic art. This ideal of a loving grief in response to the suffering of another is, it seems, a bright sadness or perhaps even a peaceful anguish – an anguish burning with the fire of love that overwhelms and transcends all before it and gives an intense joy. The first painting is 17th century by Ribera, the next three are 15th century Flemish by Dirk Bouts except for the third which is by Rogier Van Der Weyden. The next two are by Ribera and Murillo and are 17th century baroque; the final one is by El Greco, who although earlier - 16th century - conforms to baroque form in this painting.

In both sets the artist is showing constraint in portraying emotion, it is there, but there is a strong sense of peace in the expressions of Our Lady in each case.

![]() In a very hopeful move the Congregation for Divine Worship and Discipline of the Sacraments will be restructured to focus much more strongly on art and music in the liturgy. This follows directly an moto proprio issued by the Pope in September. The full article in the CNA here (h/t Sara Kitzinger).

We all keep our fingers crossed. Whether or not this has a good effect depends upon how standards are judged by those involved and how they are communicated through the Church. One of the great shapers of my sense of liturgical art and the form that is appropriate for the liturgy is the small, but rich, passage about sacred art in his book The Spirit of the Liturgy. If we see this understanding permeating what is done, then it could be very powerful.

In a very hopeful move the Congregation for Divine Worship and Discipline of the Sacraments will be restructured to focus much more strongly on art and music in the liturgy. This follows directly an moto proprio issued by the Pope in September. The full article in the CNA here (h/t Sara Kitzinger).

We all keep our fingers crossed. Whether or not this has a good effect depends upon how standards are judged by those involved and how they are communicated through the Church. One of the great shapers of my sense of liturgical art and the form that is appropriate for the liturgy is the small, but rich, passage about sacred art in his book The Spirit of the Liturgy. If we see this understanding permeating what is done, then it could be very powerful.