Nearly every artist I meet acknowledges a need for inspiration to guide creativity. The application of every stroke of charcoal or paint must be guided by a picture in the mind of the artist of what he is aiming to create. Sometimes the creation of the work of art involves a carefully thought out, obviously reasoned approach and sometimes it is or more intuitive and spontaneous. However, as long as the process is the realization of an idea and not just a random process without any thought of what the result will be (as with a chimpanzee throwing paint at a canvas) then the artists is employing his intellect and is making decisions about the form he creates. Artists need inspiration in both the formation of the original ideas; and in the decisions about how it will be best achieved.

I have read a number of books claiming to have the secret to creativity and the inspiration of the imagination, a number of them best sellers. Steeped in high emotion and cod psychotherapy, I found them all unconvincing. I have met quite a few people who read them and thought they were wonderful. While it was clear that reading the book made them feel good, none seem to be able to point to visible results in their art (that I could discern at any rate). I was looking for something that actually seemed likely to contribute to my producing better art, rather than something that relieved my anxiety.

Nearly every artist I meet acknowledges a need for inspiration to guide creativity. The application of every stroke of charcoal or paint must be guided by a picture in the mind of the artist of what he is aiming to create. Sometimes the creation of the work of art involves a carefully thought out, obviously reasoned approach and sometimes it is or more intuitive and spontaneous. However, as long as the process is the realization of an idea and not just a random process without any thought of what the result will be (as with a chimpanzee throwing paint at a canvas) then the artists is employing his intellect and is making decisions about the form he creates. Artists need inspiration in both the formation of the original ideas; and in the decisions about how it will be best achieved.

I have read a number of books claiming to have the secret to creativity and the inspiration of the imagination, a number of them best sellers. Steeped in high emotion and cod psychotherapy, I found them all unconvincing. I have met quite a few people who read them and thought they were wonderful. While it was clear that reading the book made them feel good, none seem to be able to point to visible results in their art (that I could discern at any rate). I was looking for something that actually seemed likely to contribute to my producing better art, rather than something that relieved my anxiety.

It seems to me now that the answer is so much simpler than most of these books suggest. This was to use the methods of the Old Masters of the past. All it requires of me is sufficient humility to follow the traditional forms of Western culture. A traditional art education will engender that humility by requiring me to follow the precise directions of the teacher, and by following in the footsteps of the Old Masters by regularly copying their work. (See here for me details on this aspect). No self-expression here! (This incidentally is a lot of the problem, that I could see, with many of the modern methods of trying to generate creativity. Although they might even acknowledge the need for an external source of inspiration, all the popular ones that I read in fact suggested techniques that engendered self-centred self examination that in fact did the opposite - very-loosely based, as far as I could work out on 20th-century psychotherapy methods.)

It seems to me now that the answer is so much simpler than most of these books suggest. This was to use the methods of the Old Masters of the past. All it requires of me is sufficient humility to follow the traditional forms of Western culture. A traditional art education will engender that humility by requiring me to follow the precise directions of the teacher, and by following in the footsteps of the Old Masters by regularly copying their work. (See here for me details on this aspect). No self-expression here! (This incidentally is a lot of the problem, that I could see, with many of the modern methods of trying to generate creativity. Although they might even acknowledge the need for an external source of inspiration, all the popular ones that I read in fact suggested techniques that engendered self-centred self examination that in fact did the opposite - very-loosely based, as far as I could work out on 20th-century psychotherapy methods.)

Regular prayer for inspiration is part of this, and I would say that the traditional prayer of the Church is the best. This comes back, once again to active participation in the liturgy in the fullest sense of the word. Participation in the liturgy, especially when it includes the liturgy of the hours (I have written a series of articles about the Liturgy of the Hours, here) is not only an education in beauty it is the greatest training in creativity and the most powerful prayer of inspiration and guidance.

I have spent much time with Eastern Christians. My initial contact came through learning to paint icons. One of the things that struck me about them was the way they prayed with visual imagery. It seemed to straightforward: they would stand and turn to look the icon in the face, addressing the person depicted directly. Also, they were inclined to sing their prayers in full voice. I might be with a family, for example, and before the meal, they all stood, faced the icon of Christ that was in the dining room and sang an ancient hymn. My reflections on this are in another article called Praying with Visual Imagery.

Upon further reflection, and coming back to this issue of creativity for artists, something that struck me is how unlikely it is that an artist who is not habitually praying with visual imagery is going to be able to produce art that nourishes prayer. If I am habitually making that connection between the prayer and the image, then I will instinctively produce art that nourishes my own prayer. If I am praying well, then that art will be beautiful and will, in turn, nourish the prayers of others. This practice of praying with visual imagery is developing my instincts for what is beautiful. It is also engaging my vision in the prayer, and conforming it to the liturgical practice. This is an act of humility therefore that opens the person as a whole to inspiration and guidance , with a particular focus on that faculty of the visual.

Upon further reflection, and coming back to this issue of creativity for artists, something that struck me is how unlikely it is that an artist who is not habitually praying with visual imagery is going to be able to produce art that nourishes prayer. If I am habitually making that connection between the prayer and the image, then I will instinctively produce art that nourishes my own prayer. If I am praying well, then that art will be beautiful and will, in turn, nourish the prayers of others. This practice of praying with visual imagery is developing my instincts for what is beautiful. It is also engaging my vision in the prayer, and conforming it to the liturgical practice. This is an act of humility therefore that opens the person as a whole to inspiration and guidance , with a particular focus on that faculty of the visual.

It has been said that historically, that all the great art movements began on the altar. Think of the baroque. It began in the 17th century as the sacred art and architecture of the Catholic counter-Reformation, but this set the style for all art, architecture and music, sacred and profane in both Catholic and Protestant countries.

Therefore the prayer with visual imagery in the context of the liturgy, is a hugely important factor in developing our instincts as to what is beautiful and is the bedrock for the visual aspects of all culture. Just as the liturgy, with the Eucharist at its heart, is the source and summit of human life, so liturgical art is the source of inspiration for and the summit to which all other art participates and directs us to.

I try to do the same when I am participating in the Mass. Once a month we have the Melkite Liturgy at the college and the priest very obviously turns to face the large icons of Our Lady, or of Christ when addressing them in the liturgy. I do my best to take this lesson into my participation in the Roman Rite. Similarly, at the end of Mass on weekdays we say the Angelus, and we all turn and face the statue of Our Lady which is in our little chapel.

I try to do the same when I am participating in the Mass. Once a month we have the Melkite Liturgy at the college and the priest very obviously turns to face the large icons of Our Lady, or of Christ when addressing them in the liturgy. I do my best to take this lesson into my participation in the Roman Rite. Similarly, at the end of Mass on weekdays we say the Angelus, and we all turn and face the statue of Our Lady which is in our little chapel.

The Liturgy of the Hours is a place in which, as a layman, I can do much to adopt these practices. If I pray the Liturgy of the Hours at home, I can use an icon corner to orientate my prayer. When we pray the Liturgy of the Hours at Thomas More College, we finish with invocations special to the community including addressing Our Lady and the Sacred Heart of Jesus. We turn and face these images as we pray. At Vespers and Compline we set up the icon of Our Lady because each has a strong Marian content. At Vespers we say the Magnificat, the song of Our Lady every day and at Compline we always finish with a Marian antiphon.

Of course, the use of imagery is just one aspect of engaging the whole person in prayer – appropriate use of incense, chant and posture allows for the active conformity of the whole person to the prayer and so greater openness to inspiration in any human activity. So this prayer of the artists is really a prayer by which any can hope to discover their personal vocation and flourish in it.

What does inspiration feel like? We can be transported in ecstacy, as in the painting of St Francis by Caravaggio, below, or St Theresa of Avila, right; but more commonly, the inspiration of the artist is not felt at all. We know it is has been there not because of how we feel during the painting process, but rather by the quality of the work at the end of it. Even if the painting of it felt like hard work, God might have been guiding our decision making processes. And frankly, it's going to be hard to paint if you are fainting into the hands of an angel like St Francis did!

What does inspiration feel like? We can be transported in ecstacy, as in the painting of St Francis by Caravaggio, below, or St Theresa of Avila, right; but more commonly, the inspiration of the artist is not felt at all. We know it is has been there not because of how we feel during the painting process, but rather by the quality of the work at the end of it. Even if the painting of it felt like hard work, God might have been guiding our decision making processes. And frankly, it's going to be hard to paint if you are fainting into the hands of an angel like St Francis did!

And one final point that was made to me in this regard. Inspiration is given by God and He inspires whomsoever He pleases. It is not something demanded or taken by the artist. These methods are ways that develop our ability to cooperate with Him. In the end, if it is not my vocation to be an artist then all prayer and training in the world will not make a great artist of me. However, we can take heart, it will develop everybody's ability to cooperate with the inspiration that He gives to all of us in order to carry out our personal vocations whatever they may be. So we may find that this training leads some of us to something that is, in these cases, even more fulfilling than art.

This is one of series of articles about prayer and creativity through the liturgy, the most powerful and effective form of prayer: the others are here.

Anyone wishing to learn the traditional methods of art and prayer mentioned in the article can come to the summer programme of the Way of Beauty Atelier at Thomas More College of Liberal Arts. We have traditional art and chant classes that teach the methods in conjunction with the practice of prayer. Alternatively there is a weekend retreat which teaches the principles of the prayer with the art classes. All programmes are open to people of all ages (not just high-school students).

The painting at the top is by Vermeer (17th century baroque). Other images described below each one.

The Melkite Liturgy at Thomas More College of Liberal Arts, Merrimack, NH. Chaplain, Fr Boucher turns to the icon of Christ at a point when he is addressing Him directly.

The Melkite Liturgy at Thomas More College of Liberal Arts, Merrimack, NH. Chaplain, Fr Boucher turns to the icon of Christ at a point when he is addressing Him directly.

Pentecost (Jean Restout, French, 1732).

Here are examples of cast drawings by freshman students at Thomas More College of Liberal Arts. They study the academic method of drawing. This is a method that developed in the High Renaissance and can be traced back to Leonardo. The name comes from the art academies of the 16th and 17th centuries that established it. We are lucky to have the world renowned Ingbretson Studio closeby in Manchester, New Hampshire.

During the spring semester, students spent each Saturday at the studio. This is a large sacrifice of time as they received no concessions in regard to their other studies. The results are excellent, I think you'll agree.

Here are examples of cast drawings by freshman students at Thomas More College of Liberal Arts. They study the academic method of drawing. This is a method that developed in the High Renaissance and can be traced back to Leonardo. The name comes from the art academies of the 16th and 17th centuries that established it. We are lucky to have the world renowned Ingbretson Studio closeby in Manchester, New Hampshire.

During the spring semester, students spent each Saturday at the studio. This is a large sacrifice of time as they received no concessions in regard to their other studies. The results are excellent, I think you'll agree.

When depicting Christ or Our Lady one always has to consider their individual characterics

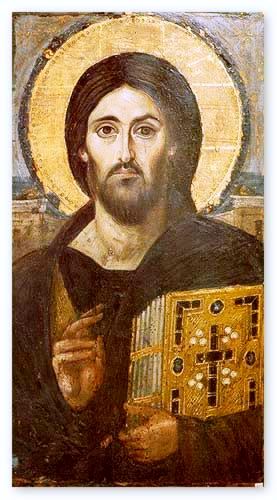

When depicting Christ or Our Lady one always has to consider their individual characterics  There are many depictions of Christ by Western European artists that show him as Western European for the same reasons. When I showed my students the Christ pantocrator, below, many assumed that this was painted in Western Europe too, and were surprised to learn that it was from Mt Sinai in Egypt. I could only offer a speculation as to why his skin tone is paler than one would expect of a working man, a carpenter, in the Middle East, which would surely have been known to the Egytians who saw this image in the 6th century. I suggested that as this was in the iconographic form, the artist would shown the uncreated, heavenly light emanating from the person of Christ. So the lightening of the skin tone is linked, perhaps, along with the other familiar features such as the halo to the depiction of this. As usual I will be interested to see if there any readers who can enlighten us (if you’ll forgive the pun) on this matter.

There are many depictions of Christ by Western European artists that show him as Western European for the same reasons. When I showed my students the Christ pantocrator, below, many assumed that this was painted in Western Europe too, and were surprised to learn that it was from Mt Sinai in Egypt. I could only offer a speculation as to why his skin tone is paler than one would expect of a working man, a carpenter, in the Middle East, which would surely have been known to the Egytians who saw this image in the 6th century. I suggested that as this was in the iconographic form, the artist would shown the uncreated, heavenly light emanating from the person of Christ. So the lightening of the skin tone is linked, perhaps, along with the other familiar features such as the halo to the depiction of this. As usual I will be interested to see if there any readers who can enlighten us (if you’ll forgive the pun) on this matter.

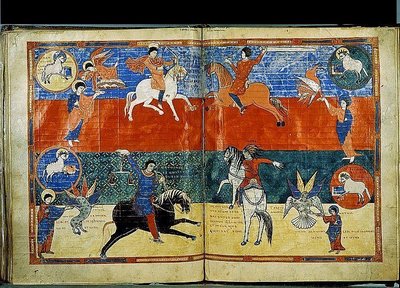

An original work of art in the Spanish Romanesque style of the Morgan Beatus Manuscript.

An original work of art in the Spanish Romanesque style of the Morgan Beatus Manuscript.

Interestingly, this ratio (5:3) appears also in the description of the construction of the Noah’s ark. St Augustine directly links the dimensions of Noah’s ark to the perfect proportions of a man, exemplified he says, in Christ. This echoes the classical proportions of the perfect man as described by the Roman Vitruvius in his textbook for architects. Furthermore, Boethius, in his book De Arithmetica, lists a series of 10 perfect proportions that he says came from Pythagoras, Plato, Aristotle and ‘later thinkers’. The final proportion of the series, called the Fourth of Four contains right at the beginning this ratio. (The references for these can be found in an article Harmonious Proportion in the Christian Tradition, here.)

Interestingly, this ratio (5:3) appears also in the description of the construction of the Noah’s ark. St Augustine directly links the dimensions of Noah’s ark to the perfect proportions of a man, exemplified he says, in Christ. This echoes the classical proportions of the perfect man as described by the Roman Vitruvius in his textbook for architects. Furthermore, Boethius, in his book De Arithmetica, lists a series of 10 perfect proportions that he says came from Pythagoras, Plato, Aristotle and ‘later thinkers’. The final proportion of the series, called the Fourth of Four contains right at the beginning this ratio. (The references for these can be found in an article Harmonious Proportion in the Christian Tradition, here.)

It seems to me now that the answer is so much simpler than most of these books suggest. This was to use the methods of the Old Masters of the past. All it requires of me is sufficient humility to follow the traditional forms of Western culture. A traditional art education will engender that humility by requiring me to follow the precise directions of the teacher, and by following in the footsteps of the Old Masters by regularly copying their work.

It seems to me now that the answer is so much simpler than most of these books suggest. This was to use the methods of the Old Masters of the past. All it requires of me is sufficient humility to follow the traditional forms of Western culture. A traditional art education will engender that humility by requiring me to follow the precise directions of the teacher, and by following in the footsteps of the Old Masters by regularly copying their work.