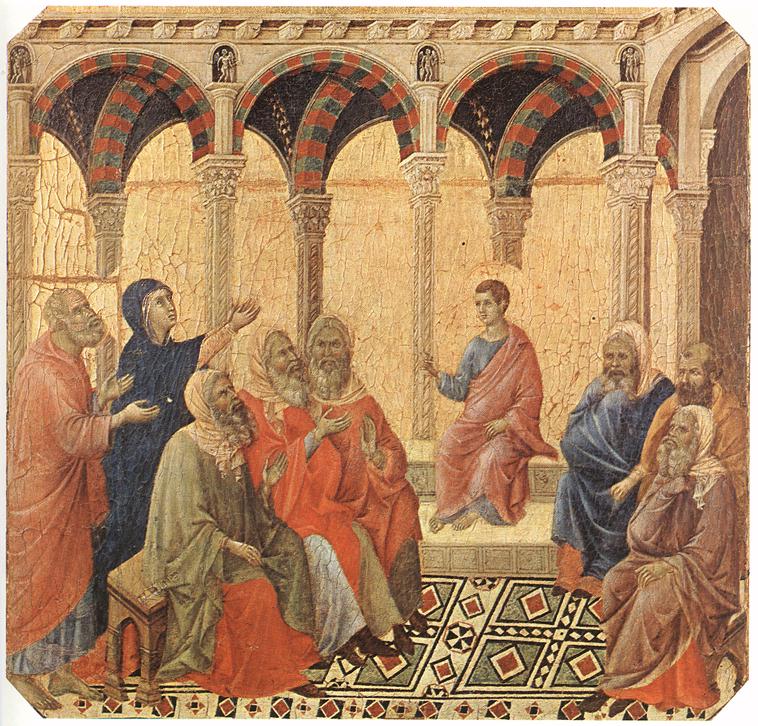

...And it passes through an octagonal portal.

...And it passes through an octagonal portal.

Liturgy, the formal worship of the Church - the Mass and the Liturgy of the Hours, the Eucharist at its centre - is the ‘source and summit of Christian life’. We are made by God to be united with him in heaven in a state of perfect and perpetual bliss, a perfect exchange of love. All the saints in heaven are experiencing this and liturgy is what they do. It is what we all are made to do; this how it is the summit of human existence. Our earthly liturgy is a supernatural step into the heavenly liturgy, this unchanging yet dynamic heavenly drama of love between God and the saints; and the node, the point at which all of the cosmos is in contact with the supernatural is Christ, present in the Eucharist. It is more fantastic than anything ever imagined in a sci-fi drama. There is no need to watch Dr Who to see a space-time vortex, when I take communion at Mass (assuming I am in the proper state of grace) I pass through one. And there’s no worry about hostile aliens, that battle is fought and won.

Everything else that the Church offers and that we do is meant to deepen and intensify our participation in this mystery. Through the participation in the liturgy, we pass from the temporal into a domain that is outside time and space. Heaven is a mode of existence where all time, past and future is compressed into single present moment; and all places are present at a single point.

Our participation in this cannot be perfect in this life, bound as we are by the constraints of time and space. We must leave the church building to attend to the everyday needs of life. However, this does not, in principle, mean that we cannot pray continuously. The liturgy is not just the summit of human existence; it is the source of grace by which we reach that summit. In conforming to the patterns and rhythms of the earthly liturgy in our prayer, we receive grace sufficient to sanctify and order all that we do, so that we are led onto the heavenly path and we lead a happy and joyous life. This is also the greatest source of inspiration and creativity we have. We will get thoughts and ideas to help us in choices that we make at every level and which permeate every action we take. Then our mundane lives will be the most productive and fulfilling they can be.

How do we know what these liturgical patterns are? We take our cue from nature, or from scripture. Creation bears the thumbprint of the Creator and through its beauty it directs our praise to God and opens us to His grace. The patterns and symmetry, grasped when we recognize its beauty, are a manifestation of the divine order.

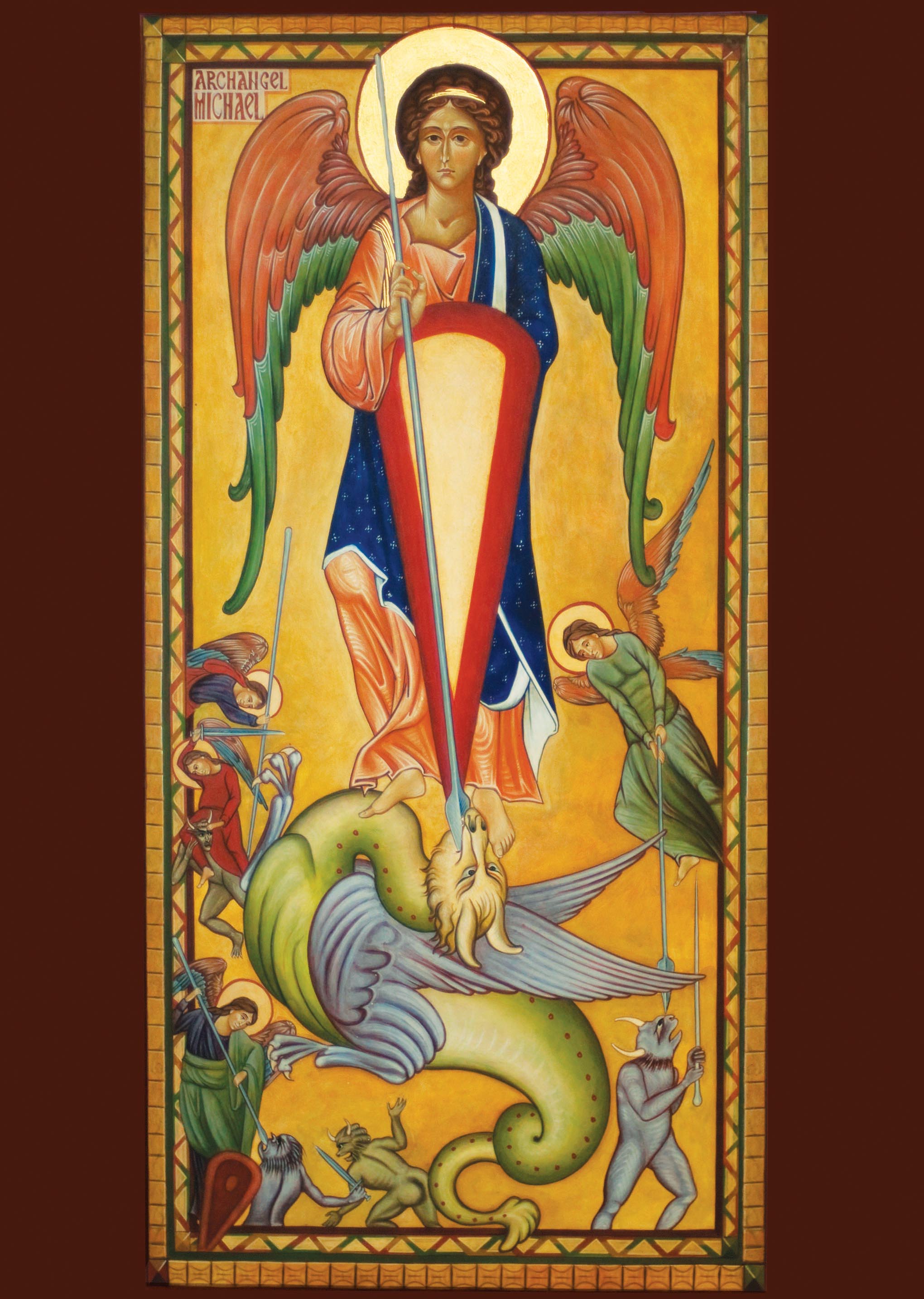

Traditional Christian cosmology is the study of the patterns and rhythms of the planets and the stars with the intention of ordering our work and praise to the work and praise of the saints in heaven. This heavenly praise is referred to as the heavenly liturgy. The liturgy that we participate, which is connected supernaturally to the heavenly liturgy is called the earthly liturgy. The liturgical year of the Church is based upon these natural cycles of the cosmos. By ordering our worship to the cosmos, we order it to heaven. The date of Easter, for example, is calculated according to the phases of the moon. The earthly liturgy, and for that matter all Christian prayer, cannot be understood without grasping its harmony with the heavenly dynamic and the cosmos. In order to help us grasp this idea that we are participating in something much bigger that what we see in the church when we go to Mass, the earthly liturgy should evoke a sense of the non-sensible aspect of the liturgy through its dignity and beauty and especially the beauty and solemnit of the art and music we use with it. All our activities within it: kneeling, praying, standing, should be in accordance with the heavenly standard; the architecture of the church building, and the art and music used should all point us to what lies beyond it and give us a real sense that we are praising God with all of his creation and with the saints and angels in heaven. When we pray in accordance with these patterns we are opening ourselves up to God’s helping hand at just the moment when it is offered. This is the prayer that places us in directly in beam of the heat lamp of God’s grace.

The harmony and symmetry of the heavenly order can be expressed numerically. For example, because of the seven days of creation in Genesis there are seven days in the week (corresponding also to a half phase of the idealised lunar cycle). The Sunday mass is the summit of the weekly cycle. In the weekly cycle there is in addition day, the so-called eighth ‘day’ of creation, which symbolises the new order ushered in by the incarnation, passion, death and resurrection of Christ. Sunday the day of his resurrection, is simultaneously the eighth and first day of the week (source and summit). Eight, expressed as ‘7 + 1’ is a strong governing factor in the Church’s earthly liturgy. (It is why baptismal fonts and baptistries are constructed in an octagonal shape and why you might have octagonal patterns on a sanctuary floors.)

The harmony and symmetry of the heavenly order can be expressed numerically. For example, because of the seven days of creation in Genesis there are seven days in the week (corresponding also to a half phase of the idealised lunar cycle). The Sunday mass is the summit of the weekly cycle. In the weekly cycle there is in addition day, the so-called eighth ‘day’ of creation, which symbolises the new order ushered in by the incarnation, passion, death and resurrection of Christ. Sunday the day of his resurrection, is simultaneously the eighth and first day of the week (source and summit). Eight, expressed as ‘7 + 1’ is a strong governing factor in the Church’s earthly liturgy. (It is why baptismal fonts and baptistries are constructed in an octagonal shape and why you might have octagonal patterns on a sanctuary floors.)

Without Christ, the passage of time could be represented by a self enclosed weekly cycle sitting in a plane. The eighth day represents a vector shift at 90° to the plane of the circle that operates in combination with the first day of the new week. The result can be thought of as a helix. For every seven steps in the horizontal plane, there is one in the vertical. It demonstrates in earthly terms that a new dimension is accessed through each cycle of our participation temporal liturgical seven-day week.

The 7+1 form operates in the daily cycle of prayer in the Divine Office too. Quoting Psalm 118, St Benedict incorporates into his monastic rule the seven daily Offices of Lauds, Prime, Tierce, Sext, None, Vespers, and Compline; plus an eighth, the night or early-morning Office, Matins.

The 7+1 form operates in the daily cycle of prayer in the Divine Office too. Quoting Psalm 118, St Benedict incorporates into his monastic rule the seven daily Offices of Lauds, Prime, Tierce, Sext, None, Vespers, and Compline; plus an eighth, the night or early-morning Office, Matins.

Prime has since been abolished in the Roman Rite, but usually the 7+1 repetition is maintained by having daily Mass (not common in St Benedict’s time). Eight appears in the liturgy also in the octaves, the eight-day observances, for example of Easter. Easter is the event that causes the equivalent vector shift, much magnified, in the annual cycle. The Easter Octave is eight solemnities – eight consecutive eighth days that starts with Easter Sunday and finishes the following Sunday.

These three helical paths run concurrently, the daily helix sitting on the broader weekly helix which sits on the yet broader annual helix. We are riding on a roller coaster triple corkscrewing its way to heaven. This, however, is a roller coaster that engenders peace.

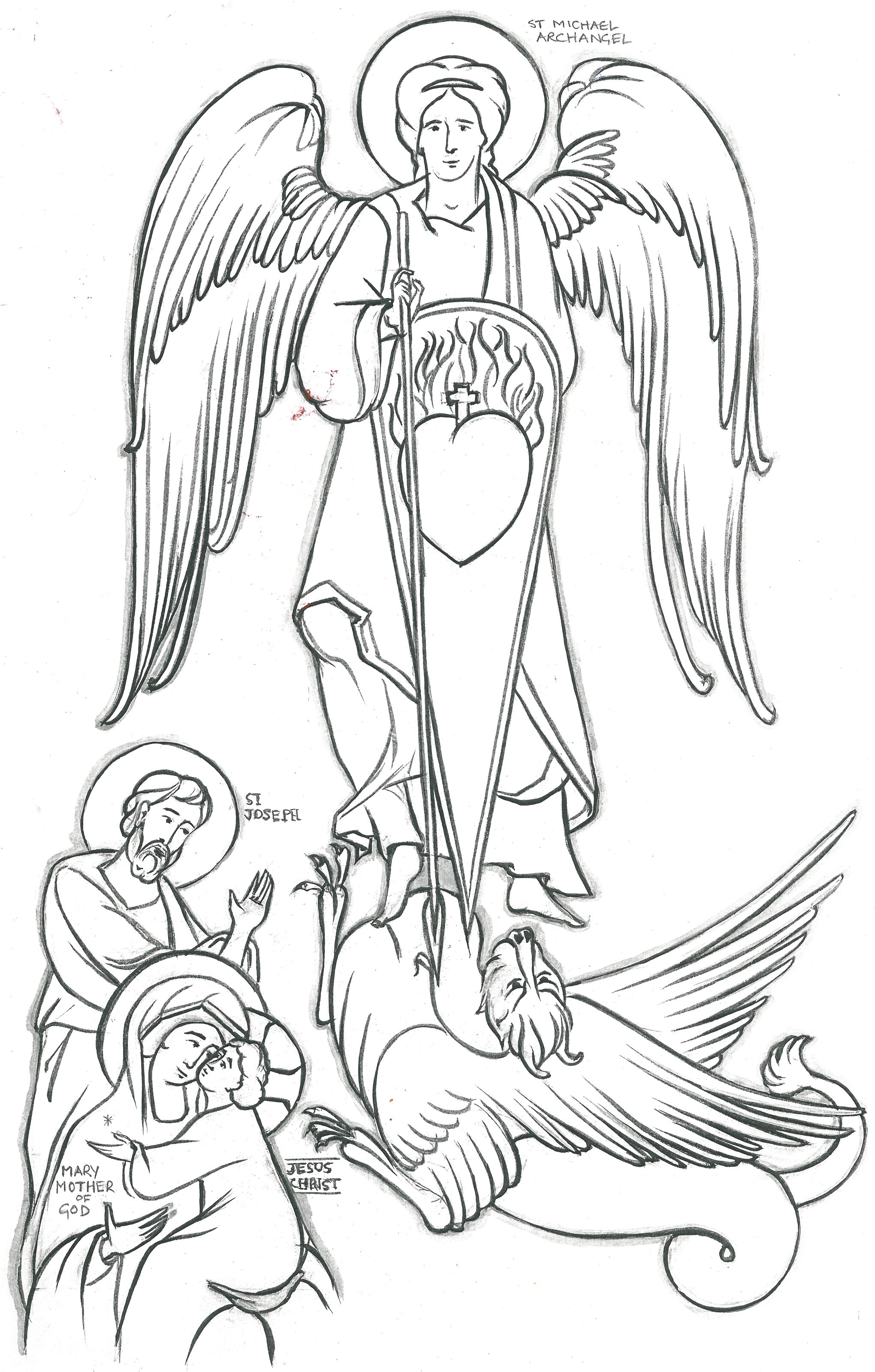

For those who are not aware of this, more information on this topic and how to conform you're life to this pattern, read The Little Oratory; A Beginner's Guide to Prayer in the Home and especially the section, A Beautiful Pattern of Prayer.

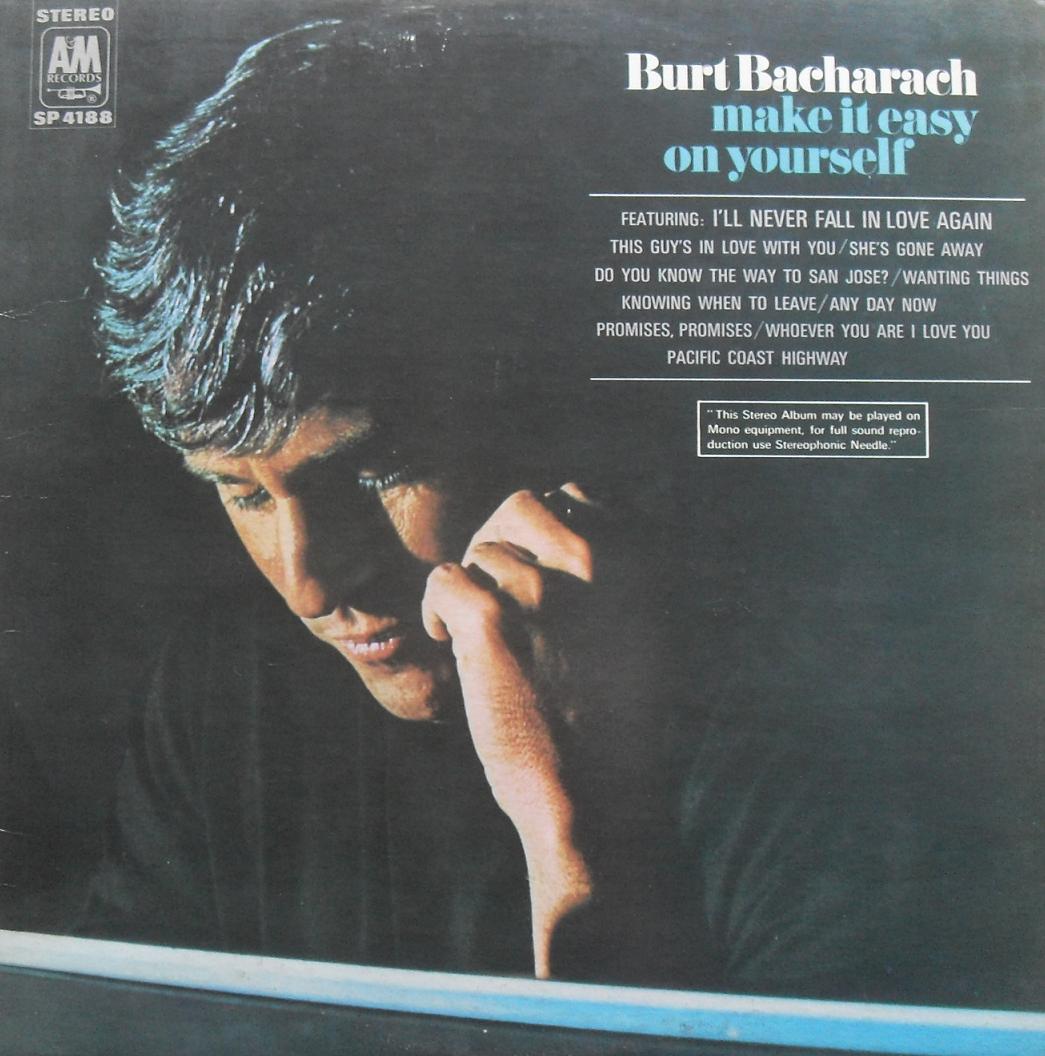

Pictures: The baptismal font, top, is 11th century, from Magdeburg cathedral. The floor patterns are from the cathedral at Monreale, in Sicily and from the 12th century. The building is the 13th century octagonal baptistry in Cremona, Italy.