In this article I describe how it is prayer, above all, that binds families together; and the most powerful form of prayer we can pray in the home is the liturgy of the hours. Furthermore, with the father leading the prayers, we are opening the way for a powerful driving force that has effect not only within the family but also beyond the four walls of our home.

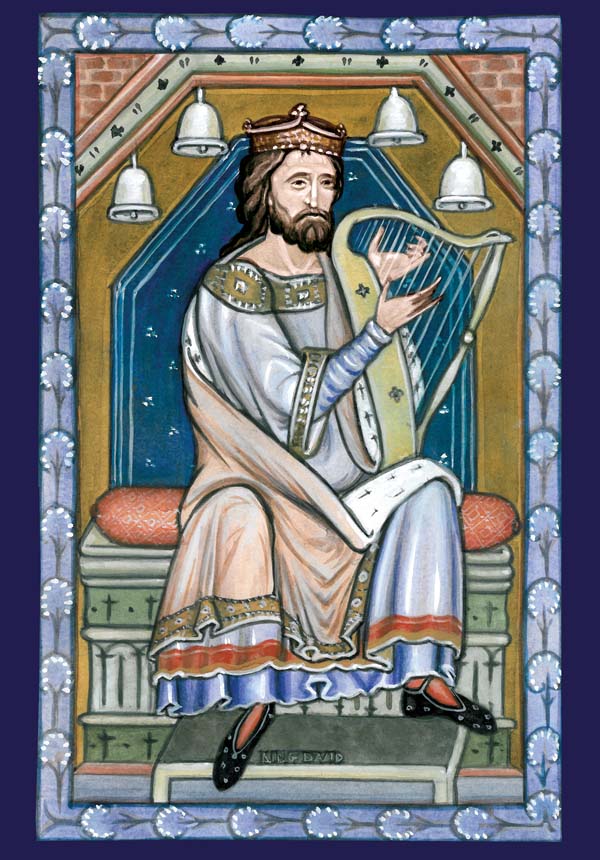

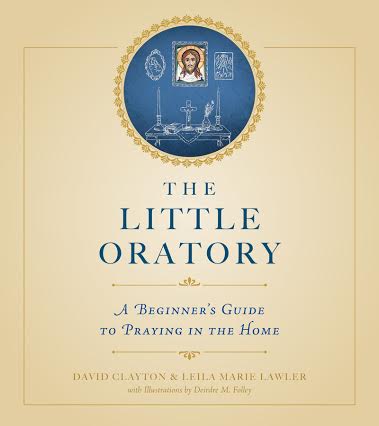

I first posted this exactly three years ago. It was in part a desire to see this home-based driving force for change that lead to the writing of the book on prayer in the home, The Little Oratory.

In this article I describe how it is prayer, above all, that binds families together; and the most powerful form of prayer we can pray in the home is the liturgy of the hours. Furthermore, with the father leading the prayers, we are opening the way for a powerful driving force that has effect not only within the family but also beyond the four walls of our home.

I first posted this exactly three years ago. It was in part a desire to see this home-based driving force for change that lead to the writing of the book on prayer in the home, The Little Oratory.

The word Oratory, incidentally means in English 'House of Prayer'. When I used to go to the London Oratory - the wonderful Catholic church in England whose liturgy was so influential in my conversion - I used to see these words on the walls around the sanctuary: domus mea domus orationis vocabitur. It was a quote from Isaiah 56:7 which is echoed in Matthew's gospel - my house shall be called a house of prayer, says the Lord. This isn't the full quote, I know there's some Latin missing there but I am handicapped by a combination of poor Latin skills and a bad memory; but here's the point, I wanted to include at least part of it because it shows the word 'orationis' - 'of prayer' - so that you can make the connection with the title of the book.

We chose this title because we wanted to communicate the idea that even the most humble house can be transformed into a house of prayer in accordance with the ideal articulated in Isaiah, and just as the London Oratory, in all its wonderful glory does. This is how a house becomes a home, however many people live there. The book we have written, we hope, helps us to fulfill that ideal and it places fathers, when we are talking of families, once more right at the centre of family and in right relationship with all others. As one might say, the father is the head and the mother is the heart. Both are necessary!

I will be doing a series of postings over the next few weeks that draw out themes discussed in more detail in the book. Anyway, here is the article....

In the exercise of the lay office in the liturgy each person participates in the sacrifice made by Christ, the supreme act of love for humanity. When we are advocates in prayer in this liturgical setting, the participation in the liturgy becomes an act of love for those people and communities with which we have a connection. Accordingly, by participating in the liturgy the family members enter into the to the mystical body of Christ who is our advocate to the Father and so participate in that sacrifice and His advocacy, on behalf of the family, too.

It is the father who is the head of the family and who is called is called above the others to be in a quasi-priestly role, and is in a special position to be the advocate to God for his family. This role is executed without diminishing or replacing the advocacy of other family members.

This role of the father as advocate to the Father is a tradition that is biblical at its source, as Scott Hahn points out: ‘[In] the Book of Genesis, liturgy was the province of the Patriarchs themselves. In each household, priesthood belonged to the father, who passed the office to his son, ideally the firstborn, by pronouncing a blessing over him. In every household, fathers served as mediators between God and their families’[1] Also, just as at Mass we pray for the head of state, family members might pray for the head of the family (and by extension, to all communities and groups that we belong to).

We hear that there is a crisis of fatherhood at the moment, and for all the ways that this manifests itself in our society, one wonders if at root, part of the cause at least is the loss of this sense of advocacy for the family by one who is assigned that special role. A visible example of this aspect of fatherhood is powerful for children in learning to pray and inspiring them to do so regularly; and valuable for boys especially as a demonstration that prayer is a masculine thing to do.

The liturgical activity of the home is the liturgy of the hours because it need not be done in a church and does not need a priest participating in order to be valid, the lay office is sufficient. The ideal therefore is that the father leads the family in the liturgy of the hours, visibly and audibly. If this were to common practice, I believe it would help to reestablish prayer as something that men do and will promote a genuine, masculine fatherhood as well as encouraging vocations to the priesthood amongst boys through this masculine example of liturgical piety.

The liturgical activity of the home is the liturgy of the hours because it need not be done in a church and does not need a priest participating in order to be valid, the lay office is sufficient. The ideal therefore is that the father leads the family in the liturgy of the hours, visibly and audibly. If this were to common practice, I believe it would help to reestablish prayer as something that men do and will promote a genuine, masculine fatherhood as well as encouraging vocations to the priesthood amongst boys through this masculine example of liturgical piety.

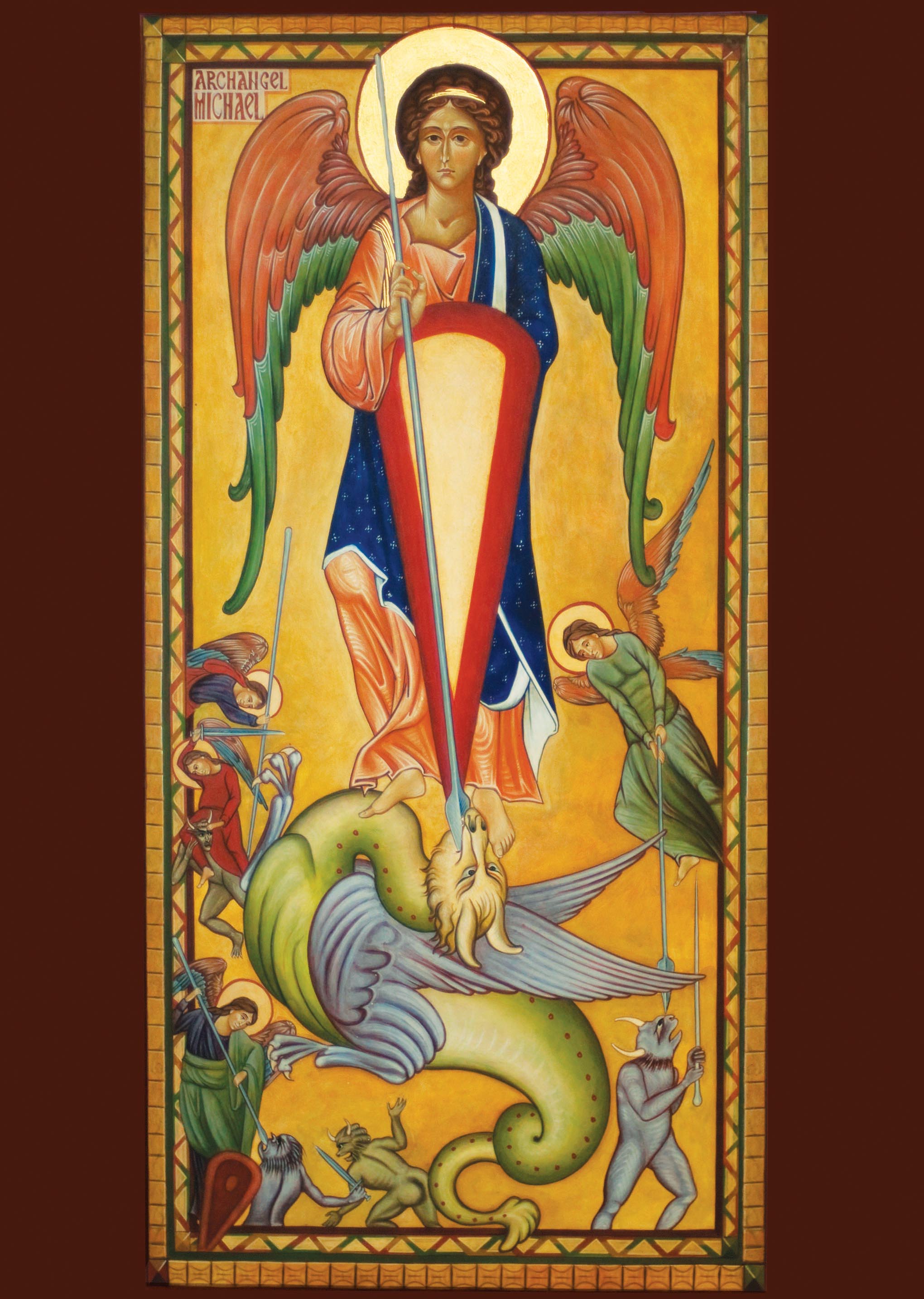

Something that would help to reinforce this is a domestic shrine. This is a visible focus in the home for prayer and the Eastern practice of creating and icon corner is particularly good for this. I will never forget seeing an Orthodox family doing their night prayers in front of the icons. The father led the prayers and all sang together or took their turn singing their prayers in the simple but robust Eastern tones. What impressed me was how all the children right down to the youngest who was four, wanted to take their turns and emulate their father. At one point two of the children argued about whose turn it was and Dad had to come in and arbitrate! They had a small incense burner burning and several long slender orange ochre beeswax candles burning in front of the icons. Each stood in reverence, facing the icon corner, occasionally crossing themselves. All the senses and faculties, it seems were directed for prayer as part of and on behalf of the family.

The families who have resolved to do this say to me that full family involvement is not always possible. It is inevitable that often family members will be too busy to join in and some will not want to. Nevertheless, the father resolved to make it clear that he was committing to regular prayer for the family and that all family members were invited at least to join in, so even if the prayer took place with only the father taking part, he was prepared to make that sacrifice on behalf of his family. And when the father is not with the family, for example if at work, he still strives to follow that liturgical rhythm of prayer and when does so, he does so on behalf of his family still.

I am only recently a father, but even when I was single and I prayed the liturgy of the hours I tried to remember to think of myself as participating in some way on behalf of my wider family and the various social groups that I am a member of, including work. Through my personal relationships, and this is still the case, those groups are present in the liturgy, to some degree, when I am. It is one way I can emulate Our Lord by participating in His sacrifice, and make a sacrifice for those with whom I relate. My hope is that will play a small part in bringing God's grace into these groups of people so that they might become communities supernaturally bound together in love. In my prayers, every morning, I consciously dedicate my liturgical activity to all those groups and with whom I am connected so I think of myself as representing my family, my friends, my work, the Church, social groups and so on, perhaps naming any individuals that are on my mind at that time. if, during the day I am not in a position to recite an hour, which can be often, I try mentally to mark the hour with a small prayer to maintain that sense of rhythm.

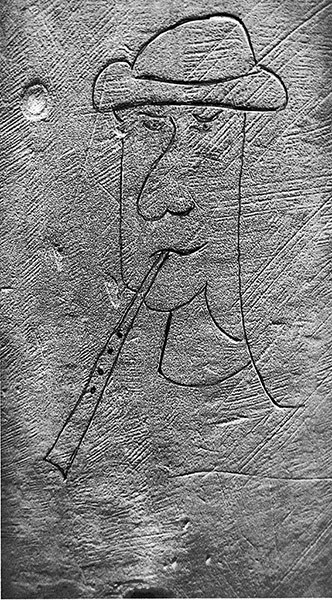

Images: top two are both paintings of the Holy Family by Giuseppe Crespi painting around the 1700; below: the Nativity with God the Father and the Holy Ghost by Giambattista Pittoni, Italian, 17th century

[1] Scott Hahn, Letter and Spirit, pub DLT, p28