If I can't trust my taste in food, can I trust my taste in art? I like chocolate cake. I don't know for certain, but I am guessing that there aren't many nutritionist out there who would argue that chocolate cake is good food. So here's the point. If the food I like isn't necessarily good food, might it be true also for the art I like?

If I can't trust my taste in food, can I trust my taste in art? I like chocolate cake. I don't know for certain, but I am guessing that there aren't many nutritionist out there who would argue that chocolate cake is good food. So here's the point. If the food I like isn't necessarily good food, might it be true also for the art I like?

Good art, I would maintain, communicates and reflects truth; and it is beautiful. There should never be any conflict between the good, the true and beautiful for they are all aspects of being and exist in the object being viewed, for example a painting. However sometimes it might appear as though there is a conflict. We might think something is false, yet find it beautiful for example.

Or that something is ugly but good. I have heard some people say that they like Picasso’s Guernica, see below, because its ugliness speaks of suffering. I would say contrary to this that if it is ugly, and it looks it to me, it must be bad. (I might go on and explain that this is contrary to truth because Christian art reveals suffering, but always with hope rooted in Christ, the Light of the World who overcomes the darkness. Such a painting, if successful will always be beautiful. what Geurnica lacks is Christian hope. ) In regard to the general principle, who is right? How can we account for these apparent contradictions between the good and the beautiful?

Many today would respond by asserting the subjectivity of the viewer. That is, they would say that my premise is wrong and the qualities good, true and beautiful are just a matter of personal opinion; and they are not necessarily tied to each other in the way I described. If they are right then there is nothing disordered about liking ugliness; or hating beauty; or thinking that something is both ugly and good at the same time.

I do not accept this. The answer for me lies in accepting that we have varying abilities to recognize goodness, truth and beauty. This gap between reality and our perception of it has its roots in our impurity. Since the Fall, we see these qualities only ‘through a glass darkly’ so to speak and our judgement, to varying degrees, can be disordered. This is where food comes into the discussion.

Now, more than chocolate cake, I love fluorescent-orange cheesey corn puffs. In England are they are called Cheezy Wotsits (pictured right...and don’t they look delicious!). I have an insatiable appetite for these wonderful dusted pieces of crunchy manna. The dust they are coated with is 'cheese-flavoured' - there's no pretence that there is any real cheese involved (and those brands where the manufacturer claims that real cheese is one of the ingredients, are inferior in taste in my opinion).

Now, more than chocolate cake, I love fluorescent-orange cheesey corn puffs. In England are they are called Cheezy Wotsits (pictured right...and don’t they look delicious!). I have an insatiable appetite for these wonderful dusted pieces of crunchy manna. The dust they are coated with is 'cheese-flavoured' - there's no pretence that there is any real cheese involved (and those brands where the manufacturer claims that real cheese is one of the ingredients, are inferior in taste in my opinion).

I could happily enjoy three meals a day consisting of nothing else and never get tired of them. But I don’t do that because I know that however much I like them they are not good food…or not if you eat them in the quantities that I want to eat them anyway. I would end up overweight and have permanently colour-stained fingers and lips.

So where does this leave us in trying to decide if a work of art is good. There are no rules of beauty by which I can decide how beautiful something is on a scale of 1-10. There is no artistic expert doing the equivalent what the nutritionist has done for the Cheesy Wotsit: a scientist with beauty meter that gives a definitive answer. For all that I might use ideals of harmony and proportion when creating art, the process of apprehending beauty after the fact is always intuitive. When I see a tree, I don’t go out and measure to see if it’s beautiful. I look at it and decide that it is. It’s just like harmony in music. The composer follows the rules of harmony, but listener just listens and decides if it is beautiful.

But the fact that it is difficult to discern, doesn't mean that it is not an objective quality. It just means that I should try to be as discerning as I can. And here's how I approach this problem: because I know that the good and the true and beautiful must all exist in equal measure in any particular object, I ask myself certain pointed questions to help me judge them and only if the answer is yes will I select the piece:

Is it communicating truth? This means that I look at the content and the form (see Make the Form Conform) and ask myself if what is being communicated is consistent with a Catholic worldview. If it isn’t I reject it, regardless of whether or not I like it.

The second question I ask myself is do I think it is beautiful? If I at least try to make a judgement on beauty then at least I stand a chance of getting it right. And this probably isn't as unreliable as you might think. When I go through this process with the classes I teach I ask them if they like a piece. Very often there is a split within the class. However, when I ask the question: do you think this is beautiful? There is almost always a much higher degree of consensus. Christopher Alexander, an architect, wrote a book in which he described an experiment he carried out. He presented people with an object and then asked a range of questions and observed the degree of consensus. He found ‘do you like this’ had a low degree of consensus; ‘is this beautiful?’ was higher; and ‘would you like to spend eternity with this?’ gave almost complete unanimity. He was framing the questions so as to get people to think gradually more about the nature of beauty, and when he did, there was consensus.

And finally do I like it? So it’s not that taste is completely unimportant, but that it is just one aspect of choosing.

If the answer to all of these is yes I choose it. Even then, does this mean that I have made an infallible choice? No. As I mentioned before, there is no visible standard of perfect beauty by which I can measure something on any verifiable ‘beauty-scale’. God who is pure beauty is the standard, and I can’t see Him. However, what this does do by using reason to some degree, is to increase my chances of getting it right.

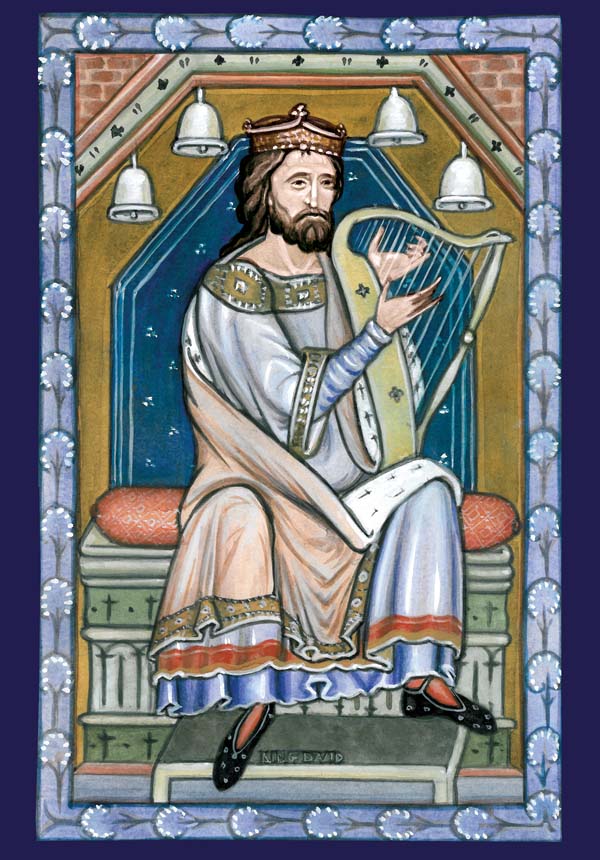

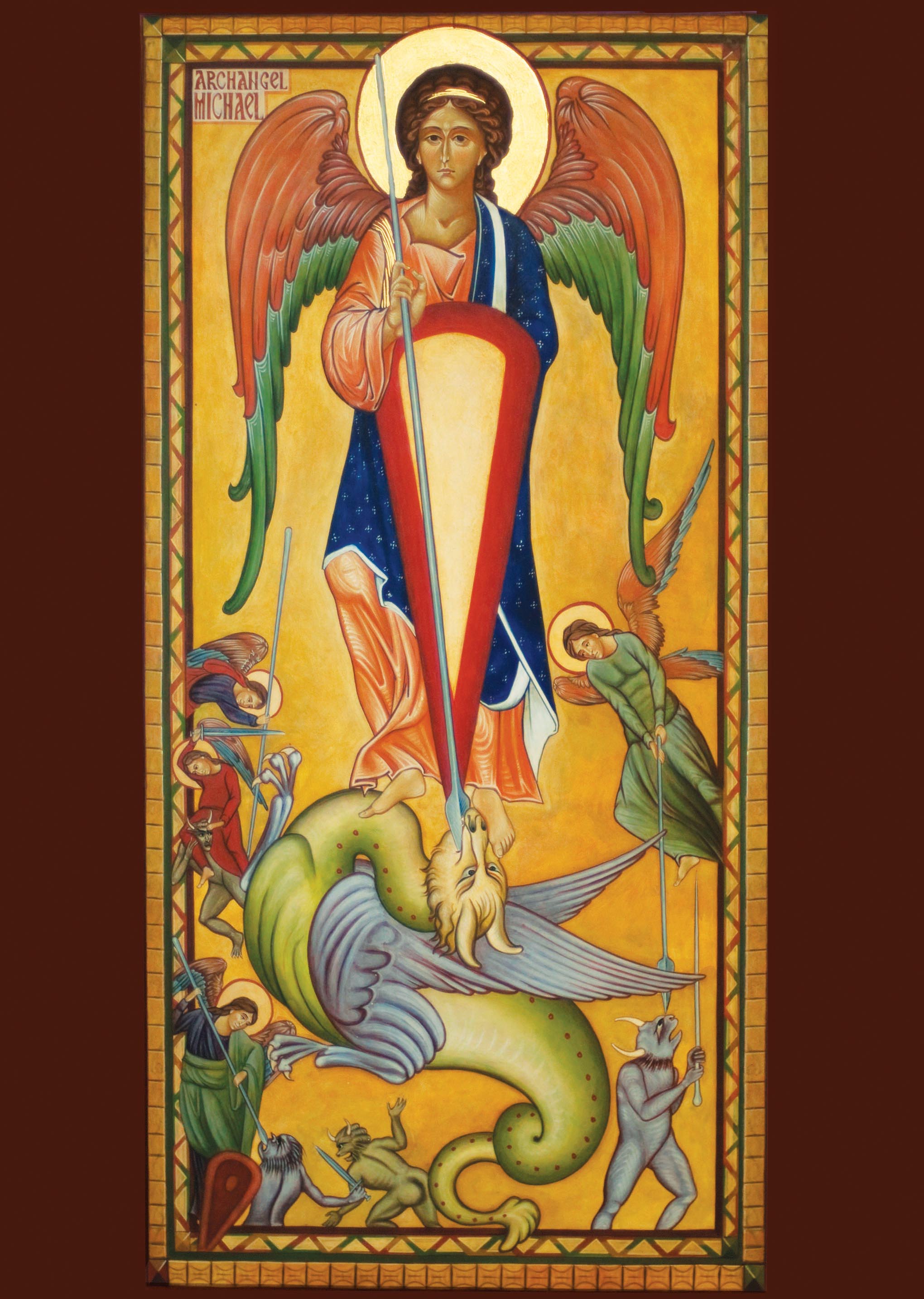

If I was choosing a piece for a public viewing, and especially a work of art for a church, I would play safe and seek not only those works that passed the above criteria when I consider my own opinion, but also for which there is a broad consensus that they are good, true and beautiful. How do I know which these are? Tradition tells me. Tradition is Chesterton’s democracy of the dead – taking the highest proportion of yesses, when considering all time, and not just the present. So for liturgical art, the authentic traditions are the styles of the iconographic, the gothic and the baroque. These styles have passed the test of time and I would choose art in these forms.

One last point, art is like food in another way. The more I am exposed to what is good, the more I learn to like it. My taste can be educated. So the more I expose myself to traditional art, the better my taste will become. Just as the more I eat salad, the more I will like it and the maybe one day I will grow out of Cheezy Wotsits...although I hope that day never comes.

.jpg&container=blogger&gadget=a&rewriteMime=image%2F*)

.jpg&container=blogger&gadget=a&rewriteMime=image%2F*)

.jpg&container=blogger&gadget=a&rewriteMime=image%2F*)