Summer Drawing Classes in the Academic Method at the Ingbretson Studios, Manchester NH

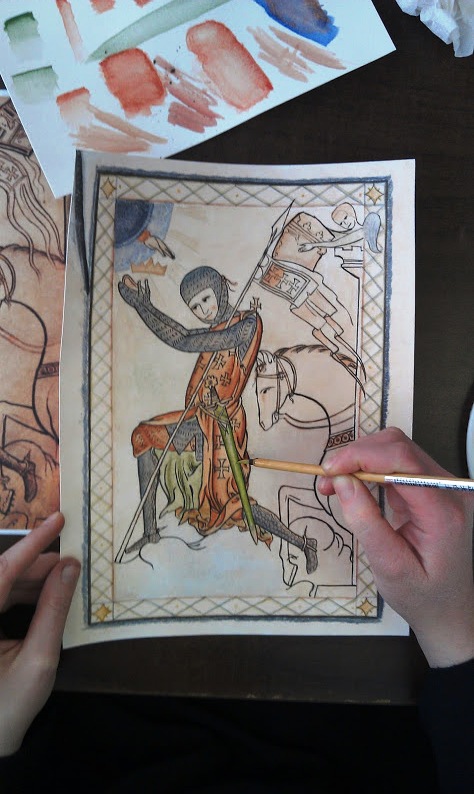

All figurative Christian art, and especially sacred art, is a balance between natural appearances and idealisation. Idealisation is the controlled distortion from natural appearances that enables the artist to communicate invisible truths.

Summer Drawing Classes in the Academic Method at the Ingbretson Studios, Manchester NH

All figurative Christian art, and especially sacred art, is a balance between natural appearances and idealisation. Idealisation is the controlled distortion from natural appearances that enables the artist to communicate invisible truths.

Some people assume that working in a style such as the gothic or iconographic is easier than in more naturalistic styles, but in fact to be able to work in a style well is takes great skill. The artist must be aware of span the divide between the two worlds he is representing. If there is too great an emphasis on natural appearances, then it lacks mystery. If the distortion so too great, then we lose a sense of the material. Artists should be aware too, that in sacred art the degree of naturalism should be less than in mundane art - for example landscapes and portraits.

Pius XII spoke of this in Mediator Dei (195) he refers to this balance (he uses the word 'realism' for my naturalism; and 'symbolism' for my idealism): 'Modern art should be given free scope in the due and reverent service of the church and the sacred rites, provided that they preserve a correct balance between styles tending neither to extreme realism nor to excessive "symbolism," and that the needs of the Christian community are taken into consideration rather than the particular taste or talent of the individual artist.'

The first step in getting this right is studying the tradition to develop a sense of where the balance lies. Even so, different artists will have a different sense of exactly where this balance lies, but even recognition of the fact that there can be excessive naturalism and excessive abstraction and that he should seek the temperate mean goes a long way to getting it right.

The second step is getting the skill to represent precisely both the naturalistic and the idealistic (by reflecting accurately the idea of the mind in the artist). The artist who cannot draw well from nature cannot do this, for no matter how well conceived his ideas may be he cannot represent them accurately if he cannot draw well. Therefore learning to draw well is an essential part of the training of any artist. Regardless of the style in which he ultimately intends to paint in, I would recommend everyone to learn to draw rigorously. The best drawing training that I know is the academic method. I spent a year learning this in the Florence atelier of Charles H Cecil with the blessing of my icon painting teacher even though the style is very different. As a result the quality of my icon painting went up by orders of magnitude. A danger of learning the academic technique is that of being so dazzled by how ones drawing improves that one forgets that technique is only the means to an end and not the end. The artist must realise that he cannot succeed on technique alone and so should not neglect the development of his understanding tradition and how to direct those skills in the service of God.

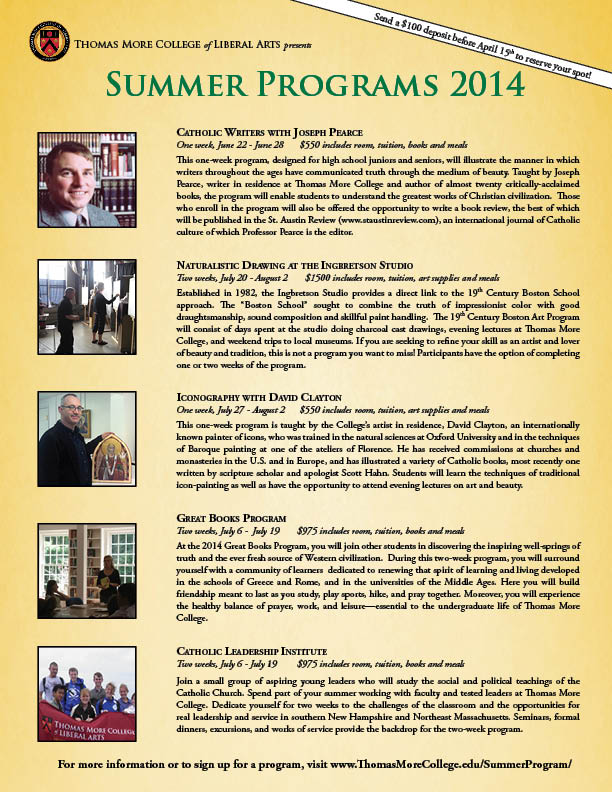

Those who wish to learn this technique can come along to the Thomas More College summer school art program. This is done in conjunction with the world reknowned Ingbretson Studio, featured here:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fbtBW2T50p0 In this class a day spent in the studio is supplemented by a series of lectures explaining the basis of the tradition and placing the use of it within the context of Catholic sacred art so that you always control the technique in the service of the Church.

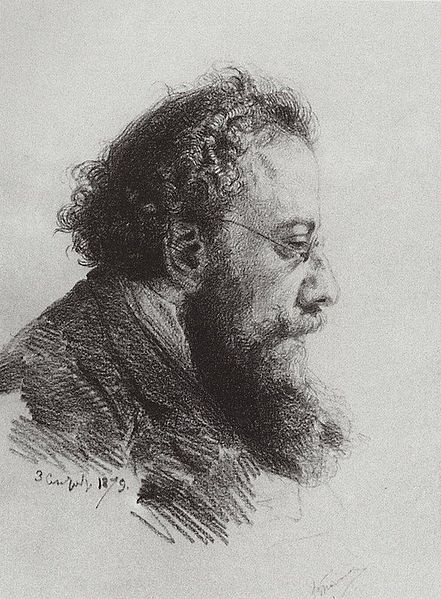

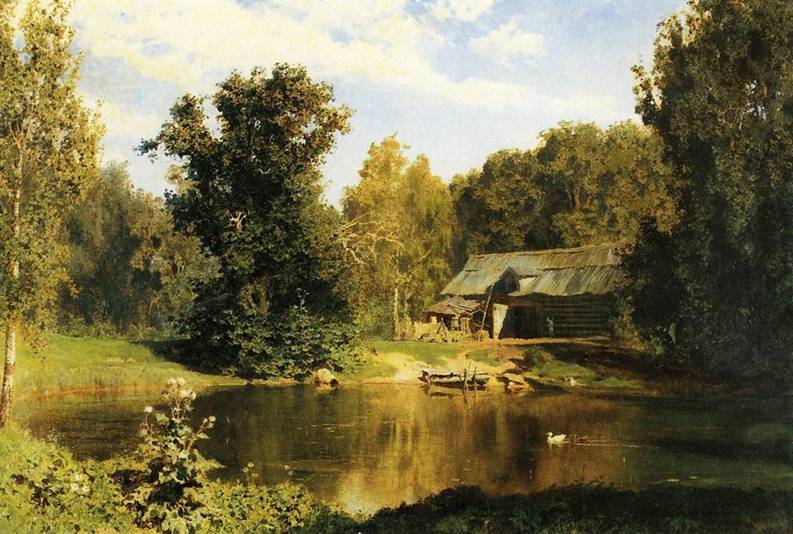

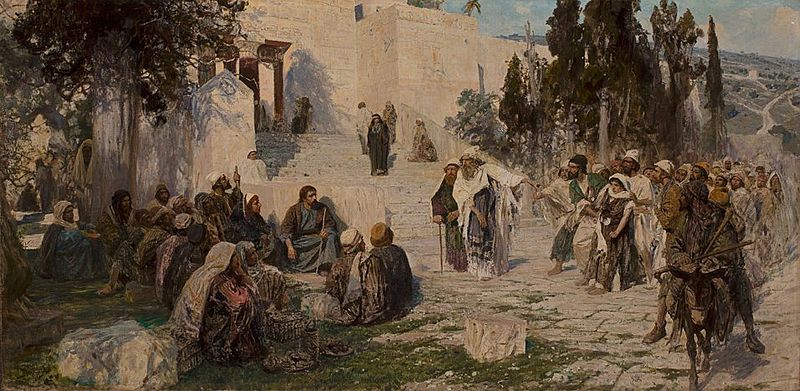

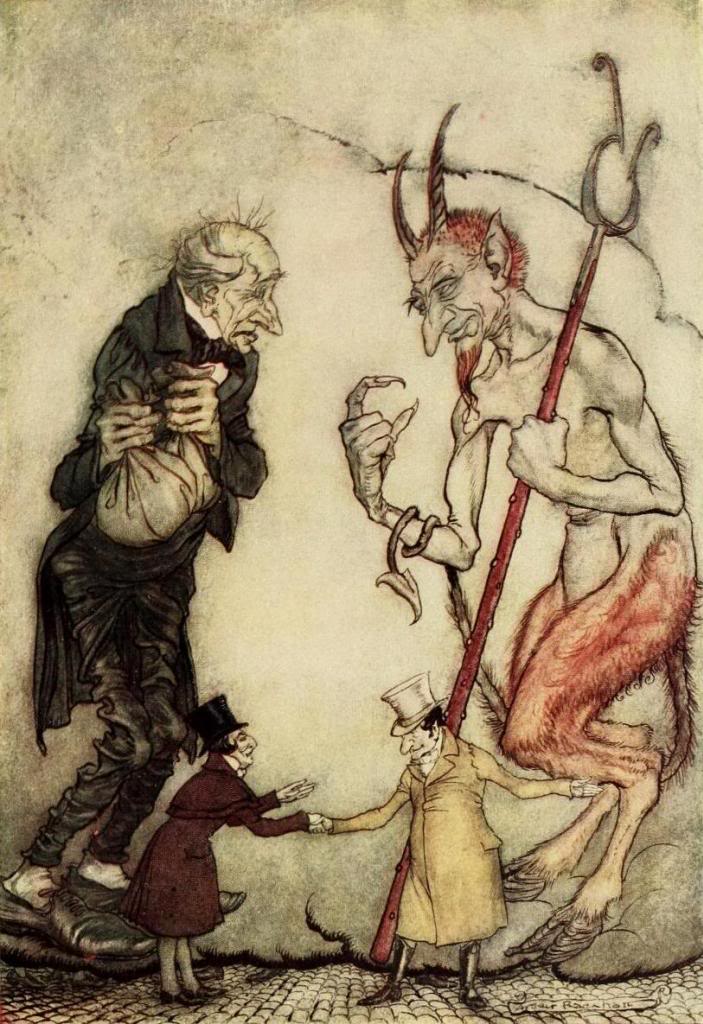

Just to illustrate the level of drawing skill achieved by the academic method. Here is work from the Russian 19th century Master Vasiliy Polenov. He is highly skilled. You can see a couple of examples of his drawings including one of a bibilical scene - the raising of the daughter of Jairus. I have also included a couple of his landscapes.

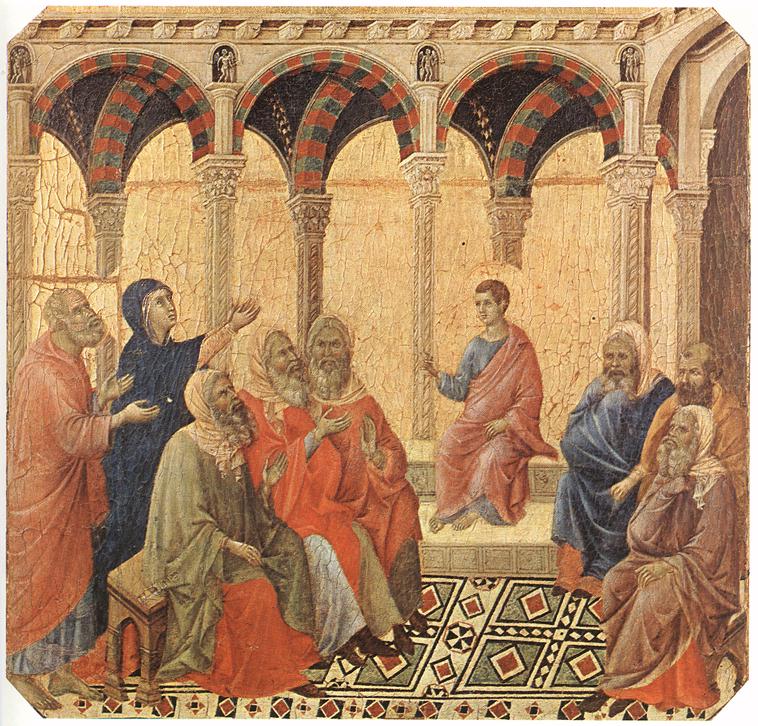

In my personal judgement, he was a superb draughtsman and has dazzling technical skill. This works wonderfully in the landscapes. However, it is not sufficiently abstracted or symbolic for sacred art and so his bibilical scenes look more like what we used to seeing as color plates in children's bibles than devotional art. It is interesting to note that in Russia in the 19th century, this is how art for churches was painted and part of process of reestablishing the Russian iconographic tradition, which happened in the 20th century as reaction to this by figures at the turn of the last century such as Fr Pavel Florensky. His analysis was then picked up by painters such as Ouspensky and Kroug in the mid-20th century.

The purpose of this not to argue against the validity of the academic training. In fact it is the opposite, I would argue that it has great value; but if one is to use it in the services of sacred art, one must be aware of how to direct that skill towards the right balance of naturalism and idealism. This is the special element, expressed in an explicitly Catholic way, is included in the classes I have described above, and which is absent from nearly all others.

Below: first, the raising of Jairus' daughter in full, then a drawing - portrait of an art critic; a superb landscape of a Russian rural scene; then two bibilical scenes - 'he who is without sin' and the boy Jesus found in the temple teaching the teachers. By way of contrast I show Duccio's version of the same subject that has a much more abstracted style.

And here is a poster for the summer drawing class run by TMC and the Ingbretson Studios